Amidst the catastrophe of COVID-19, segments of the population globally experienced changes in their perspectives on life and the desire to live a more fulfilling life. The study here examines this emergent trend with secondary data available as published survey reports and personal observations using the inductive-reflective method of understanding and theorizing. The findings support the identification of five facets of this new mindset, namely, rise in altruism, growing community-mindedness, increasing focus on health and financial security, searching for work-life balance, and increasing experiences with nature. To channel this emergent mindset, this study proposes five categories of urban innovations: (1) revival of neighborhoods; (2) expansion of parks and nature; (3) investment in urban transportation and greenspaces, (4) incentivizing entrepreneurs for ecology and local “maker economy,” and (5) staging community projects for collective good. The study describes the benefits of these innovations to general population and sets an agenda for urban planners, city managers, and social agencies as citizens begin their ongoing COVID lives. The study closes by advancing ten research proposals for future social science contributions in innovation and knowledge

The current ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has turned our personal worlds upside down. Many have been delivered severe health and economic blows. Some have witnessed the debilitating sickness and death of close family or friends. Many who managed to escape the disease or unemployment still experienced considerable upheaval in personal, family, work, and social life. Lockdowns and social distancing exacerbated loneliness and isolation, especially among those with already thin social networks and those lacking internet access or skills. Shifting of work and children's schooling and childcare to home added to the chaos and work overload in everyday living (Springer, 2020).

Economically vulnerable citizens of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the majority of the world's population resides, face stark threats to their livelihoods from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. A recent meta-study (Egger, et al. 2021) of over 30,000 respondents in 16 original household surveys from nine countries in Africa (Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda, Sierra Leone), Asia (Bangladesh, Nepal, Philippines), and Latin America (Colombia) documents declines in employment and income in all settings beginning March 2020 and beyond. Across the 16 studies’ survey periods, between 9 and 87% of respondents were forced to miss or reduce meals (median share, 45. Even in Colombia, the country among the nations sampled with the highest per capita GDP and thus potentially the greatest financial resources to cope with the crisis, the majority of respondents reported drops in income (87%) and employment (49%), and an increase in food insecurity (59%). Innovation and skill-building knowledge are necessary to respond to these severe reductions in quality-of-life that likely are impacting the majority of citizens globally. For example, Eggers et al. (2021) conclude that policymakers in LMICs will need to craft creative solutions to develop income-generating activities with longer gestation periods in case the risky COVID-19 disease environments or the associated economic slowdowns persist for a prolonged period (e.g., decades). For instance, “graduation programs” that combine assets and training can promote a source of livelihood that requires limited external contact have reduced poverty in some contexts (e.g., Banerjee, et al., 2015). “On an optimistic note, the innovation and technological adoption that takes place during emergencies can spur long-run economic development…. Solutions that arise in the current climate thus have the potential to both improve resilience immediately and durably advance the financial ecosystem.” (Eggers, et al. (2021, p. 11).

Beyond one's personal life, the specter of catastrophes everywhere, of death statistics, of media reports of overcrowded hospitals with patients left abandoned, patients dying of shortage of oxygen ventilators, of dead bodies abandoned, of mass graves and mass cremations on pyres of scarce wood—this barrage of visual images of human suffering is bound to affect the psyche of people en masse. And, as various surveys have revealed, it did (López-Cabarcos, 2020; Stein, 2020; Yasgur, 2021).

One specific outcome we expected was that living though the pandemic would make at least some people rethink their lives and modify their perspective for life, going forward.

This expectation provided the motivation for and purpose of this research: To identify the changes in people's perspectives on life to guide their future life journeys and, in turn, to develop a framework of innovations by communities and urban governments to channel, support, and respond to these new perspectives. Our data sources were the natural experiment of communities living under COVID-19 and published press and survey agency reports of people's subjective experiences of life under the pandemic and lockdowns. Our method was “participant observations” as we too lived in and shared the same world under the pandemic siege (Atkinson & Hammersley, 1994). From a critical review of these data and critical reflections, our principal discovery was the emergence of a “virtuous mindset” in a segment of the public. With further critical reflections, we identified five manifestations of this virtuous mindset—specific life themes and new behaviors the citizens planned to pursue in life, going forward.

Next, the study here draws on observations and reflections about how people and communities are rearranging their daily lives and, to facilitate that, how urban governments are restructuring large and small urban environments. Applying this understanding, the study here develops five urban innovations that public and social agencies should consider adopting so as to harness and channel the newfound virtuous mindset. The present study's principal contributions include an agenda for action by public agencies, a set of reflection-based propositions for future research in applied social sciences and management at large, and plausible exemplars for social scientists to blend academic research and the call of public wellbeing in times of adversity. The proposed agenda for public agencies and urban innovations is an urgent call for the ongoing COVID-19 era so as not to miss the opportunities afforded by the emergence of the virtuous mind.

Research questionsLiving through the ongoing pandemic and recurring lockdowns supports insightful observations of the social and communal world around us and nurtures reflections on how neighborhoods and communities are adjusting their lives and expressing their own reflections on life. A catastrophe of the COVID-19 ongoing magnitude is bound to alter people's perspectives (Van Tongeren, 2020) and offer a natural experimental setting for scholarly induction (Petticrew et al. 2005; Rothchild, 2006). Spurred by this contextual opportunity, this study provides answers to the following two research questions. RQ1. As people experienced the pandemic and lockdowns, how did their perspectives about their own lives and their world change? Going forward, how will they modify their life goals and behaviors? RQ2. What innovations in infrastructure and services should urban governments and social organizations make in order to channel and support the emergent life perspectives of its citizenry as we come out of the pandemic?

The following sections describe our method and data for the enquiry.

MethodThe intuitive inductive reflective method of theory generation, different from a deductive hypothetical method (Rothschild, 2006) is the study's approach to theory development. In the latter method, existing theory is used to create hypotheses, which are then verified with quantitative, empirical data. In contrast, the inductive reflective method examines a phenomenon qualitatively from which patterns that explain the phenomenon inducted intuitively. Upon further reflection, a narrative is created that lays out the linkages and influences between various forces that underpin that phenomenon. Useful explanations of these theorizing methods are available in Cetina (2014) and Kuczynski and Daly (2003).

Imagine that a catastrophe unfolds in a limited, distant geographical location in one community. To study the citizens’ experience of that event, researchers will have to visit there and make personal observations. The worldwide occurrence of COVID-19 made the entire world, and therefore, our own cities—where these authors lived—a study lab. We became “participant observers” (Atkinson & Hammersley, 1994) to a large-scale unfolding health and sociological event, witnessing at close quarters people's responses as individuals and as communities. In an exposition of ‘intuitionist theorizing,’ Cetina (2014) explains the method of participant observation thus:

Let me begin with the reality that our intuitive theorizer confronts. This is an argument about the nature of the reality we encounter, and about how reality serves as a resource for the intuitive system as it accomplishes its task. … The intuitive processing system needs experience to develop any intuitions. It needs to lay itself open to the reality it will end up theorizing about and be able to engage with it in ways I have glossed as “observation.” Observation can [simply] mean “being there” in the environment we try to theorize.… [observation] amounts to the “exposure” of the intuitive human processor to whatever it is that happens in a field of study. (Cetina, 2014, p. 40)

The data include media reports of people's experiences elsewhere as well as of local and state governments’ responses to help their citizens navigate the pandemic. In addition, the study utilizes survey research reports published in research and journalist media. Also, we obtained access to selected data from a research colleague (Anonymous, 2022) who had earlier surveyed a national sample of population for how the pandemic might change their worldviews.

With these observational and informational data as inputs for our critical review, we reflected and formulated our intuitively realized categories of changes in the mindsets and perspectives of people and communities. Separately, we reflected on the responses of local public agencies in terms of modifying urban infrastructures and programs (e.g., parks and recreation) and in an intuitive-inductive mode, we developed categories of urban innovations, some occurring in nascent forms then, but all of them with future as our target timeframe. Keeping our categories of the people's emergent perspectives as background cognitive map for ourselves, the categories for urban innovations also took the form of innovation clusters that would respond to the former set of categories.

This conceptual paper is in the tradition of Barr (2020), Bavel et al. (2020), Florida et al. (2021), Goddard (2021), and McGuirk et al. (2020), among others. Bavel and 41 coauthors invoke selected concepts of psychology (e.g., emotion and risk perception, ingroup elevation, social context, etc.) and reflect on how these concepts could inform effective pandemic responses. McGuirk et al. (2021) look at the “forced experimentation” in urban governance in the wake of COVID-19 and then “reflect on the actors taking center stage as cities’ responses … and the [innovations in] governing mechanisms.” Their reflections pertain to the organizational processes evolving to deal with the crisis, without speaking to the substance of the actions.

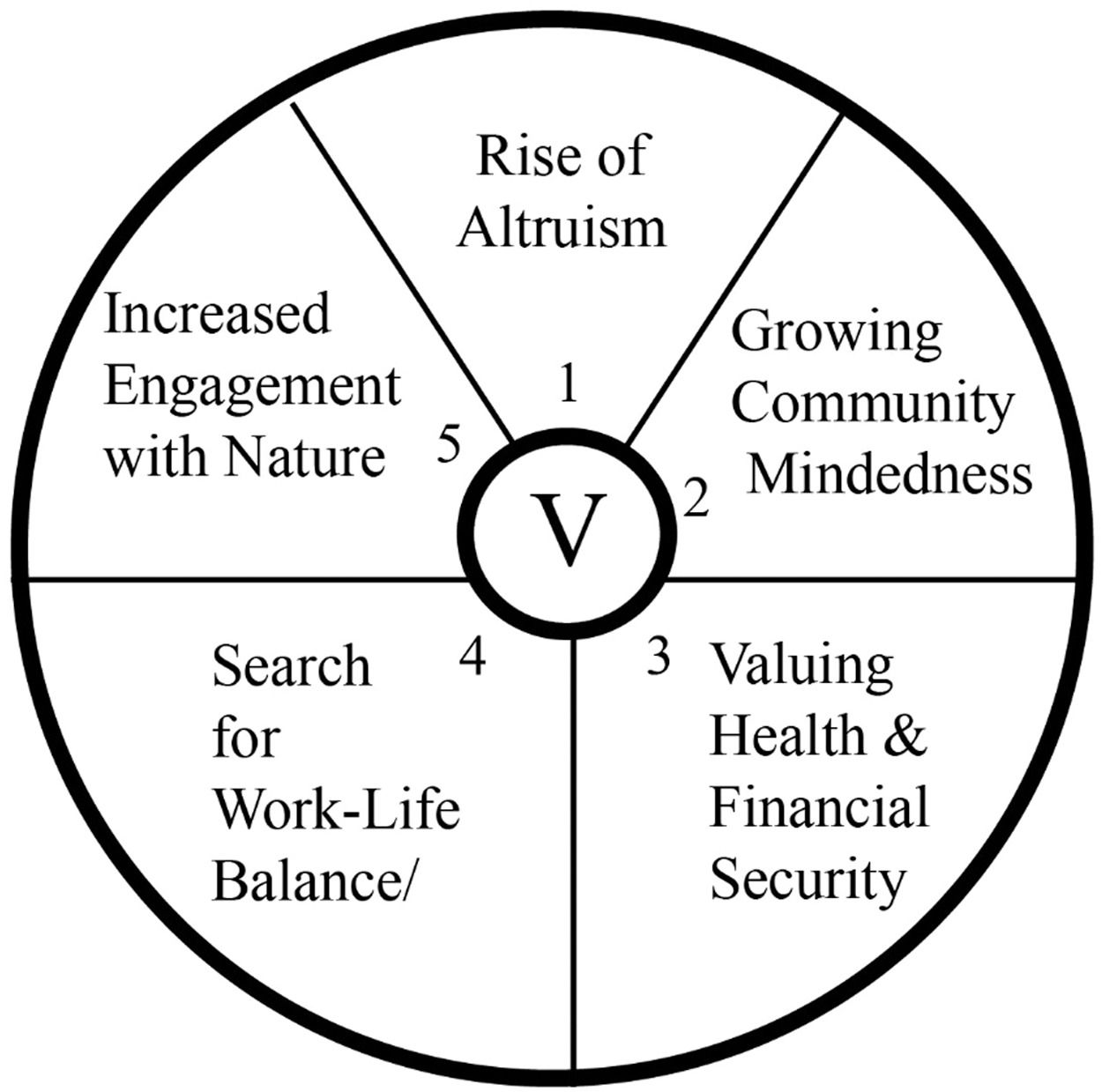

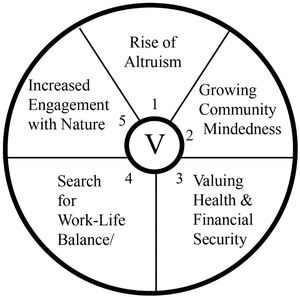

Barr (2020) uses reflection to develop narratives on six areas of research that would help Canada's social purpose sector recover and move forward from the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, in a conceptual paper, and using the reflective-narrative method, Goddard (2021) identifies some facets universities should consider to move toward becoming more of a “civic university” (either formally as part of a network or informally by simply slanting its teaching and research agenda toward local population's problems). Florida et al. (2021), using the same inductive-reflective approach, develop “suggestions” on how the pandemic “may bring about a series of short-term and some longer-running social changes in the structure and morphology of cities, suburbs and metropolitan regions.” Our paper tackles a set of different and new issues in urban and social agency response to the pandemic. The study dwells not on the essential government role of fighting the pandemic, but instead focuses on the opportunities the pandemic provides in as much as it alters the life perspectives of citizens and creates a “virtuous mindset” in a segment of the population and the indicated urban innovations to harness this mindset, in the ongoing COVID-19. The study develops a narrative on the five facets of the “virtuous mind”. Figure 1

Five Facets of the Virtuous MindsetThis inductive-reflective process focuses on citizenries and RQ1. How does the pandemic change people's way of looking at life and the social world around them? We contemplated on what we were observing, and what we were reading in press and other journalistic reports. In addition, we analyzed the survey data that we had obtained access to. This survey had sampled the Qualtrics population (a national panel of respondents), with N=550, a part of which relates to our first research question. The findings of this survey (hereafter, the Qualtrics survey) are summarized in Appendix 1. As we make references to this survey's findings, it must be noted that these empirical survey findings are but one data point and one kind of evidence. In larger part, our discovery derives from our intuitive-inductive reflections. These reflections, grounded in our participant observations, led us to identify the emergence of a “virtuous mind” in a segment of the population, and we account for this pandemic-generated “virtuous mindset” as comprising five changes in values and outlook: (1) rise in altruism, (2) growing community-mindedness, (3) valuing health and financial security more, (4) search for work-life balance, and (5) increased engagement with nature. The following discussion elaborates on each dynamic.

Rise of AltruismAltruism is the practice of performing an act for the welfare of other people at the cost of some sacrifice of one's time, money or energy (Morrison & Severino, 2007; Post, 2005). It is the opposite of egoism, which comprises being selfish or self-centered and engaging in acts that will benefit oneself even at the cost of others (Becker, 1976; Kowalski, 1997). In sociology, it is considered an ingredient in building a good society, when individuals “come to exhibit charitable, philanthropic and other pro-social acts for the common good” (American Sociological Association, 2012). Altruism and empathy are correlated, with altruistic people also empathizing more with others who are suffering (Burks et al., 2012; Floridi and Craig, 1998). Therefore, people who were characteristically altruistic felt empathetic toward those suffering from the illness and economic hardship brought on by COVID-19. Jamil Zaki (2020) refers to this as the rise of “catastrophic compassion”. Accordingly, people whose altruism level is already high experience a further rise in their altruism. And even a modest degree of pre-existing altruism suffices to ignite empathy with those suffering in plain sight; therefore, exposed to the suffering in a large swath of people, even people with a moderate level of altruism will feel a rise in their level of altruism (Vollhardt & Staub, 2011). Prior research has shown that in shared adversity situations, people display more altruism (Drury, 2018). Of course, people with near-zero altruism are characteristically over-focused on themselves and are able to emotionally separate themselves from those who suffer. Thus, we would expect low altruism to continue to thrive in such people's self-centered worldview. We believe that such bi-modal distributions will obtain on almost all dimensions of the public's mental makeup in the ongoing COVID world. However, of value here is the group that has experienced a rise in altruism (Chan, 2017; Dasgupta, 2020).

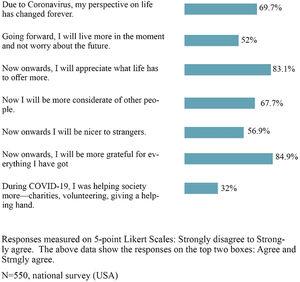

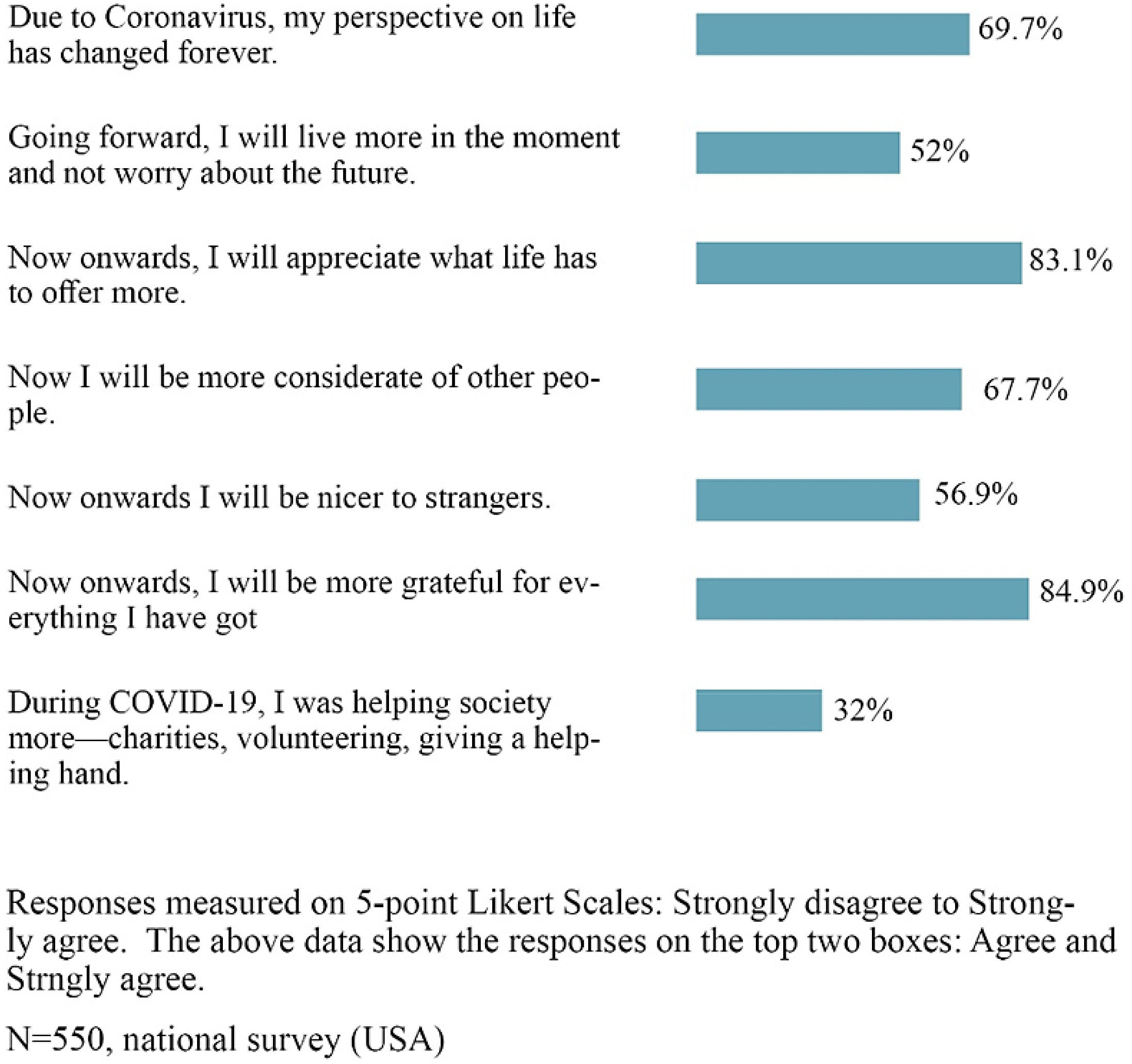

Research reports confirm this trend. People were in general more willing to contribute to charitable causes and to engage in more unselfish acts. In an experimental study, Jin and Rye (2021) made the COVID-19-engendered mortality threat more salient for a treatment group, and the respondents in this group, compared with the control group, engaged in more altruistic acts. A report by the Gates Foundation found that 56 percent of US households gave to charity or volunteered in response to the pandemic, with a 12.6% increase in new donors (Vox, 2020). A study by Charity Navigator (a tracker) reveals Who already, reveals that donations to Feeding America increased 1,980 percent year over year, and donations to Doctors Without Borders increased 131 percent year over year (Vox, 2020). According to a UN report, prosocial behavior and volunteering surged during COVID-19 globally: In France, Tous Bénévoles (translation: All Volunteers) registered 40,000 new volunteers; in Italy, 60,00 new volunteers signed up for Red Cross; in the Netherlands, 48,000 new volunteers signed up (Maggioli, 2021). Finally, in the Qualtrics national survey that we consulted, 32% of the respondents reported “helping the society more—charities, volunteering, giving a helping hand.” Overall, a significant proportion of respondents agreed that their perspective had changed toward feelings and intentions that signal the cultivation of an altruistic mindset (see Figure A1 and Table A1).

Growing community-mindednessAn increasing sense of community cohesion due to COVID-19 is a development in citizens’ mindsets. Because the pandemics hit everyone and public health measures require consideration of others, these shared responsibilities raise people's awareness of their interdependence (Eisenhauer, 2020). During COVID-19, people came to understand that it is an epidemic that is spread by people to people, among friends and among strangers alike. This leads to a realization of interdependence among all people in a community, neighbors as well as those we encounter on the street as strangers (Saladino et al., 2020). Independent versus interdependent self-concept is an established trait in the psychology literature (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Experiencing the same pandemic with the same suffering as other people will make people move more toward embracing the mindset of interdependence. This perspective is corroborated by Athena Aktipis, a psychologist at Arizona State University, who in her worldwide survey found that people increasingly agreed with statements including, “My neighborhood and I rise and fall together” and “All of humanity and I rise and fall together” (Aktipis, 2020). Public health agencies often invoked this idea of interdependence as they urged citizens to comply with the prevention guidelines to protect their own health as well as the health of other people (FDA, 2020). In the Qualtrics survey, 67% of the respondents agreed, “I will be more considerate of other people” (see Figure A1).

The realization of the role that citizens as a collectivity play in keeping citizens’ environments healthy is another aspect of this community-mindedness. The ongoing pandemic raises climate awareness for two reasons. One, in cities and towns where pollution was high, the pandemic spread faster and infection rates were higher; second, the forced lockdown reduced vehicle traffic on the road and consequently, the air everywhere was lighter and cleaner, and people noticed that (Fattorini & Regoli, 2020; Kunreuther & Slovic, 2020; Wyns, 2020). These two observations made people realize the connection between climate and the heightened risk of the spread of viruses in the future (Mende & Misra, 2021).

Every trend this study describes is defied and belied by segments of citizens who harbor deeply entrenched opposite values. “Virtuous values” is not growing among large segments of national populations necessarily—such a transformation is occurring in catalytic slivers of populations, as evidenced also in the verbatim reports in the Qualtrics national survey (See Table A1). Thus, those who are self-focused rather than other-focused or have been politically energized to embrace more parochial interests will stay unmoved by the suffering of others; those who already denied science or climate warming would likely find their attitudes even more hardened. Yet, there is a segment, considerable in size, whose attitudes have turned more positive and intensive toward community and climate (Pew Research Report, 2020; Subhashini, 2020).

Valuing health and financial security moreThe instillation of a high degree of fear (Porcelli, 2020) is the greatest impact an ongoing pandemic like COVID-19 has on people. Infection from an epidemic is a risk that one may attempt to guard to prevent but may yet not avoid. And once caught, it can wreck unpredictable toll on one's health, including causing a death. This risk was brought home every day as TV News reported on mounting infections and deaths. Survey data offers evidence of a substantial proportion of people being in distress—45% in the USA, 35% in China, and 60% in Iran (United Nations, 2020).

Media reports also communicate about the higher vulnerability of those already in poor health (Nguyen et al., 2020; Whitehead et al., 2021). People in poor health not only have a higher probability of catching the virus, but they also face the likelihood of more severe illnesses (Centers for Disease Control, 2021; Mayo Clinic, 2021). Faced with such threats, people value their health more and resolve to take new measures to take care of their health (Weaver et al., 2021). Protection motivation theory (Rogers, 1975) is useful for explaining these outcomes. In prior research, protection motivation theory has been used to predict condom usage with the advent of AIDS (Eppright et al., 1994; Lwin et al., 2010). In protection motivation theory people cognitively assess a threat and channel their self-efficacy to preventively thwart future threats. In the Qualtrics national survey, one respondent stated, “I think life is short so I will be more careful, and I will try to keep myself healthy” (see Table A1).

Simultaneously, the ongoing COVID-19 causes many people job losses and income reductions. A national survey in April-May 2020 by Social Policy Institute at Washington University found that 24% of people had lost their jobs or had their incomes reduced, the highest level since the Great Depression (Despard et al., 2020). A University of Southern California survey revealed that from April 2020 to March 2021, 48% of Americans experienced financial insecurity.

Search for work-life balanceBeyond health and financial consequences, the pandemic and the resulting lockdowns had altered our daily life's reality in yet another way. It put in sharp contrast our work lives and our personal lives. Most of us adopted to working from home and thus spent more time with families. Many people came to see anew the family as a new source of joy in ways they had not previously experienced. At the same time, they realized that life is fragile, and that realization made them want to not let work consume so much of their time that they had no time left for their families. Furthermore, many had engaged in new creative and recreational activities, such as cooking, gardening, art & craft, etc. And this too made them value their personal pursuits more (Büssing, 2020; Collins, 2020). As one respondent in the Qualtrics survey put it: “I have realized that life is too short to waste time not doing what I truly love. I will live every day to the fullest.” Another respondent said, “Give my work-life balance more priority” (see Table A1). In effect then, many wanted to spend less time at work and make available more time for friends and families and for creative hobby projects (Parker et al., 2020). In the Qualtrics survey, 83% of the respondents agreed with the statement, “Now onwards, I will appreciate what life has to offer” (see Figure A1). The Great Resignation, unfolding even as we write, validates this development in people's mindset (Tappe, 2022). Simply put, ongoing COVID citizens want more work-life balance.

Increased Engagement with NatureThe lockdowns curtailed our usual out-of-home activities: we did not have access to our usual places to visit outside of home. For most of us, our visits to offices and workplaces stopped. For students, all on-campus classes were suspended. The stores and malls were no longer open. No restaurants were open for us to go out to dine, no pubs to go to socialize, no gyms to go to work out, even no church to congregate at. Our usual work hours were spent at our desks, in our bedrooms, basements, or at kitchen tables. As a result, we all experienced a pent-up desire to get out of the house. Fortunately, one place was still available: Outdoors—on sidewalks in our streets, in our backyards, and in the nearby parks and open fields. Accordingly, we began spending time outdoors, walking, exercising, relaxing, picnicking, even socializing at 6-foot distances (Volenec et al., 2021). A World Bank Report cites walking as the newest, hottest trend during 2020-21 (Worldbank.org, 2020).

A survey of 2,000 homeowners found that Americans were spending 3 hours a week more outdoors now than pre-Covid (Baker, 2021). A University of Vermont survey (Arnold, 2020) of 3,200 residents found a considerable increase in all outdoor recreational activities: watching wildlife (up 64%), gardening (57%), taking photos or doing other art in nature (54%), relaxing alone outside (58%), and walking (70%). A 2021 study analyzed Google location-tracking data and found significant increases in park usage worldwide during the pandemic's first wave (Geng, 2021). A survey in Scotland found that during the pandemic, 34% of Scots were getting a daily dose of nature, compared to 22% prior to lockdown (NatureScot, 2020).

All over the world, the amount of time that people spent outdoors had peaked in early 1990s and had been declining since (Smith, 2020); the 2020-21 uptick is a welcome reversal of that trend. And we discovered the “feel good” benefits of outdoors and of being in nature. The respondents in a survey by the University of Vermont said being in nature, they felt a greater sense of mental health (59%), appreciated nature's beauty (29%), sense of identity (23%) and spirituality (22%) (Arnold, 2020).

Urban Management OpportunitiesRQ2: what innovations in infrastructure and services should urban governments and social organizations implement? Here, the study focuses on the second half of the lived reality during the pandemic: That lived reality was constituted not only by how people thought about and responded to the pandemic and the lockdowns, but also how these responses were constrained or framed by the living environments of our cities and communities. City and state governments modified (or allowed businesses to modify) physical configuration of spaces for altered usage; parks and outdoor areas were closed or opened as the pandemic waxed and waned (Manzini et al. 2021). And citizens themselves created new ways of engaging themselves and new ways of interacting as communities; e.g., residents in Italy and indeed around the world sang from their balconies (Taylor, 2020). We reflect on these improvisations, by citizens themselves or by their local governments and social agencies, as examples of urban innovations. Looking at the “soft data” (our participant observations and reading press and research reports), we intuit a spectrum of urban innovations by public agencies, some unfolding in ad hoc, improvised manner.

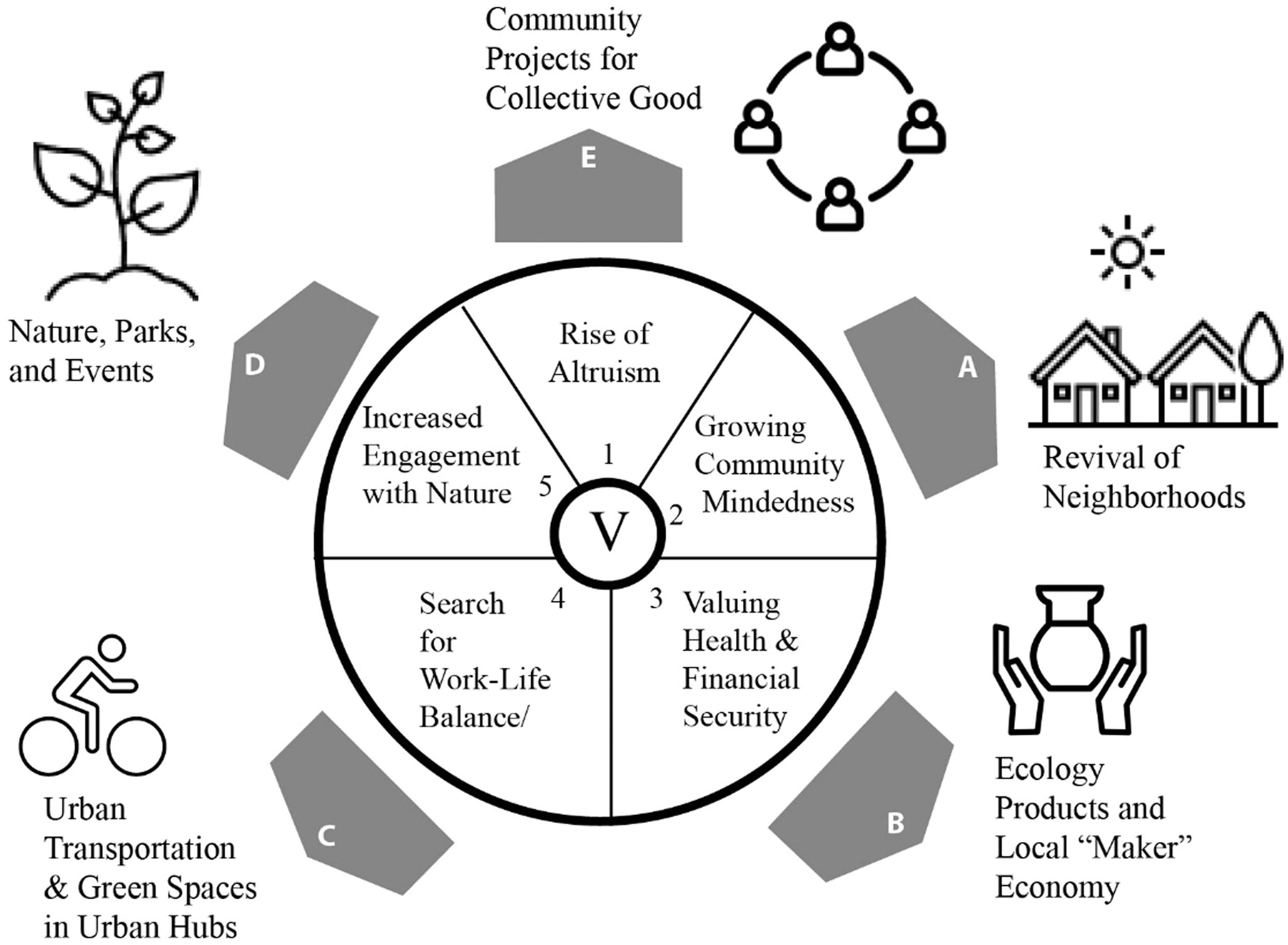

The literature is vast on urban innovations as urban development strategies over the prior thirty years (Cruz & Paulino, 2022; Gil-Garcia et al., 2016; Nam & Pardo, 2011). These developments are accounts of innovations for normal times, as the population of a city grows. Instead, the focus here is on innovations that will help the citizenry cope with an ongoing COVID world. We organize these urban innovations also under five categories. These five are not exhaustive; they are important and they are also the ones that will respond to the five facets of citizens’ new mindset. These five innovative projects that urban management agencies could undertake to harness and channel the newfound virtues among the citizenry are: (a) revival of neighborhoods, (b) ecology products and local “maker economy,” (c) urban mobility and greenspaces within urban hubs, (d) nature, parks, and events, and (e) community projects for collective good. See Figure 2.

With urbanization and modernization, neighborhood housing has become, basically, a collection of houses without much social cohesion among people. Suburban houses are often fenced or separated living quarters, with little interaction even among the residents of adjacent dwellings. In urban and multi-story apartment buildings, where living quarters are in each other's face, residents nonetheless remain strangers, practicing good-intentioned stranger courtesy, but shying away from deeper connections. In the ongoing COVID-19 era, in contrast, a felt need among (some) residents to seek environments that offer organic opportunities for congregating. Village governments might mandate (or incentivize), for example, that new neighborhoods build a courtyard, or a mini garden and picnic park, preferably with a small body of water. (For silent benefits of a body of water, see Heid, 2020). In already established suburbs (which were designed for the commute to work and malls), small-scale shopping needs to be brought closer to neighborhoods, implementing the so-called “15-minute city” concept (15minutecity.com; Bloomberg.com, 2020). This prototype of self-sufficient “micro cities” is ripe for replicating across the nation, across the world.

In new home constructions, “bring nature indoors” features such as sunlight, ample windows, and balconies will be demanded by many, and home builders will do well to find ways of incorporating these without significant cost increases or build them as “must-have” health features in lieu of less essential luxury options. Multi-family housing complexes should consider adding such health and hygiene features as touchless entrances, bigger elevators, wider hallways, more beckoning staircases, interior courtyards and atriums, multiple exit ways opening onto outdoor patios, a bike pod for the entire building, or a bike rack just inside of the apartment door (Briseno et al, 2020). Individual home building companies may not foresee the need for or utility of these amenities; therefore, city and county governments may have to play a more proactive role by crafting guidelines and, where necessary, enacting ordinances.

With the predicted increase in work-from-home options (Parker et al., 2020), many inner-city residents are “quitting the city” and moving to suburbia. As early as July 2020, homes in Montclair, N.J. (a suburb mere 12 miles from New York City), for example, were witnessing a bidding war with eager buyers offering up to 30% premium over the asking price (Berliner, 2020). Not all city residents will look to (or be able to) buy a suburban house, of course, but used to paying exorbitant rents in high-rise rental apartments near big commerce centers, they will welcome the option of renting one as much for saving in the rent as for the freedom from living in cramped spaces. In the ongoing Covid-19 era, therefore, there will likely be a demand for single-family built-to-rent homes away from cities with high densities.

While the commercial sector would happily build such new housing units, local governments will need to play a key role in directing their development. First, city governments will need to craft standards and policy guidelines to ensure better health amenities in the interiors as outlined above. Second, city governments will need to develop comprehensive plans to steer new home constructions as an integral part of self-sufficient micro cities, complete with green spaces, shopping, food, healthcare, fitness, mobility, and recreation facilities within, say, a 5-mile radius, with some convenience and grocery stores within walking distances. Third, urban governments will need to invest capital in developing affordable housing for low-income and disadvantaged segments of the population, also with the same “15-minute-city” blueprint. As one example, Liverpool (UK) has developed a GBP 1.4 billion recovery plan that includes modular houses and community centers for the city's most deprived neighborhoods (BBC.com 2020).

Ecology Products and Local “Maker Economy”With the enhanced awareness of the link between the pandemic, health, and climate change, urban governments may encourage diverse entrepreneurs and merchants of ecological and locally produced products. Such encouragement might entail incentivizing and offering business guidance to local entrepreneurs as well as organizing show-and-tell public tours to the shops of local artisans and small cottage factories (see Pipa & Bouchet, 2020). The so-called “maker economy” has been on the rise over the last decade. “Maker economy” is the place-based production of utilitarian or artisan products on a small scale by individual entrepreneurs, artists, craftsmen, and businesspersons, using local resources and for sale in local markets (see Makerfaire, 2021). Farmers’ markets represent a classic example, but the range of products now extends to cleaners, candles, soaps, clothing, shoes, handicraft, jewelry, kitchen tools, even 3d-printed products (Center for Urban Research, 2016). A University of Cambridge research project in 2020 identified the need for local government support of the local maker industry (Corsini, et al., 2020).

A World Economic Forum report (Bergman & Dart, 2021) highlights the need for “stimulating growth through entrepreneurship … to address rising unemployment caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.” City governments could act as "connectors, evaluators, and interlocutors" to support local entrepreneurs (Bergman & Dart, 2021). In every city, the bureaus of economic development, local chambers of commerce, and small business development organizations have their work cut out for them if they wanted to channel the rising ongoing pandemic demand for consuming local and more ecologically friendly products.

To take “local production” one step further, public agencies could promote 3D printing by individual consumers. Rindfleisch and Kim (2021) cite a pioneering case of the recent use of this technology. At the University of Illinois Margolis Marketing Information Lab, mask buckles were manufactured on 3D printers and supplied to hospitals. 3D printing machines cost less than $300 and design patterns are downloadable digitally from design depositories such as Thingiverse.com or YouMagine.com. Website All3DP.com lists 25 such depositories. All3DP also lists 50 “cool things” that are manufacturable with 3D printers: modular shelves, lamps, planters, rachets, credit card wallets, bottle openers, pen holders, phone stands, even beautiful tealight holders. Local governments could catalyze 3D printing entrepreneurship, acting as hubs of information and demonstration, machine and raw material sourcing, and even small loans, using at least three avenues: 1. By encouraging art and craft stores to add this activity to their activity pool, e.g., current “Paint Nite” (paintnite.com), DIY pottery craft studios such as littleshopny.com; 2. organizing 3D printing days in local museums, schools, libraries, youth clubs, other social organizations; and (3) encouraging individual households to buy the machine as a hobby for printing products for own use and for sale. This last avenue is along the lines of the recent trend in the home brewing of beer. Since 2015, home brewing has been on the rise and the market for mini brewing machines is projected to register revenues of $30 million from 2019 to 2025 (PRnewswire.com, 2020). Researchers can expect the “virtuous mind” segment to be the “innovators” of this in-home 3D printing hobby. If local governments were to promote commercial craft-studio-based and home-based use of 3D printing machines, its audience will likely spread well beyond the virtuous-mind segment. Indeed, this modern technology, with its adoption catalyzed by public agencies, could well become the new “cool” pursuit, especially among millennials, in the process reducing the world's carbon footprint.

Urban Mobility and Greenspaces within Urban HubsThe 2019-22 pandemic is sparking a heightened interest in climate-friendly consumption. This transformation implies an opportunity for urban management to make it more convenient for people to use public transportation, with an assurance of hygiene and health safety (e.g., cleaning with ultraviolet light). Also, to encourage non-motorized personal transportation, urban planners could consider building more bike lanes and bike parking pods on busy downtown city streets and near shopping centers. Seattle has plans, for example, to permanently close 20 miles of road to vehicle traffic and create “healthy streets.” In July 2020, Middlesbrough (UK) launched a city-wide rental e-scooter program, and a similar program was underway in Rome, Italy (Booth, 2020).

In some towns, DORA (i.e., “designated outdoor refreshment areas”) have taken root; these are vehicle-free streets in the middle of busy urban shopping districts, allowing people to drink their brew on the street or simply hang out. Going forward, every city, satellite city, and microcity could try to have one or several of these. Relatedly, sidewalks themselves may need to be widened, with occasional benches installed. Psychologically speaking, a long sidewalk with occasional benches (compared to no benches) will inadvertently encourage more people to walk. The goal would be to structure the urban physical environment so as to elicit natural physical movement among visitors and residents, harnessing the “nudge” strategy. (For a technical guide for urban planners, see Pierantoni, Pierantozzi & Sargolini, 2020; Urban and Rural Engineering, 2020; also, Landais et al., 2020.)

The green features (e.g., sunlight, large windows, and outdoor patios) suggested in the development of new housing in new neighborhoods also apply to commercial buildings in business districts. City governments could promote even more “green space” innovations in this sector. One such innovation is the new HVAC systems that take in 100% outdoor air rather than recirculating the same air (Purdue University Newsroom, 2021). A big part of future urban planning should be the development of more and more green spaces within the city. The pandemic has brought city dwellers closer to nature and green spaces within the city are known to have a positive impact on mental health and reduction of stress caused by fast city life (Douglas & Douglas, 2021; Frumpkin, 2021; Geary et al., 2021; NatureEngland.org.uk, 2021). These green spaces can be built on existing land/ground space in three ways: (1) green corridors, e.g., small trees and plants lining the streets and boulevards; (2) pocket gardens in spaces between stores, around the corners, portions of parking spaces, and elevated surfaces, such as the High Line in NYC; and (c) vertical farms in abandoned buildings and rooftop gardens and farms atop large commercial buildings. Rooftop gardens and farms offer multiple benefits. First, they fill the food availability void if the food supply system is disrupted as in a pandemic (Colorado, 2021); second, they conserve soil, feed on compost made from food waste, and use collected rainwater; third, even in normal times, they provide fresh organic produce to city dwellers and restaurants; and fourth, they reduce the carbon footprint by eliminating the transportation of food from far away farms, and they also cool the city (Thomaier, 2015).

Urban farms can be soil-based, but they use far less land area, thus making them possible on rooftops; they can also be aeroponic (grown in water), making them feasible in interior vertical, shelf-like or tubular spaces. Urban farms have been “growing” over the last few years: Chicago has 500 green rooftops and 13 rooftop farms. Nature Urbaine, Paris (France), named by The Guardian as “the World's Largest Urban Farm” produces 1,000 kg of 35 different varieties of fruits and vegetables (Henley, 2020). Brooklyn Grange runs three rooftop farms in New York City, producing over 100,000 lbs. of organically grown produce per year (Brooklyngrange.com). These farms are mostly commercial endeavors. Therefore, local governments will not need to invest capital; rather, they will need only to catalyze their adoption by the owners of commercial buildings big and small. For some restaurants, these are even becoming a brand distinction; for example, Baker's Cay Resort, Key Largo, Florida (USA), a Curio Collection by Hilton, uses its rooftop farm produce for its own kitchen, thus priding itself on farm-to-fork foodie trend (Coolidge, 2020).

Urban farms and green spaces both within the buildings and on the street offer four simultaneous benefits related to: 1. Climate—reducing carbon footprint; 2. Fresh organic food; 3. Mental and physical health; and 4. Community building: research has found that as occupants of a building congregate around rooftop gardens and green spaces, and people walk or bike leisurely on green streets, they tend to engage more in casual social interactions and also psychologically feel a sense of being part of a place-based community (e.g., Eunice, 2021). These benefits respond well to the heightened health consciousness and community-centered altruism in the ongoing pandemic era.

Nature, Parks, and EventsThe pandemic is turning people to walking and outdoor sports (e.g., basketball, tennis, etc.). Walking has been reported as the hottest new trend during 2020-21 (worldbank.org 2020; humankinetics.com 2021). This habit, of immense benefit to personal and collective health, should be supported by a city's infrastructure. While many cities have big flagship parks; there will be an advantage to bringing the parks to more and more neighborhoods, small scale, a park, say, within every 5 miles. Parks with children's activities and some simple exercise equipment for adults (e.g., an overhead or monkey bar, steps, cornhole sets, etc.) would help. Rodgers (2020) argues the urgency for nourishing and protecting our urban green spaces in an ongoing pandemic world.

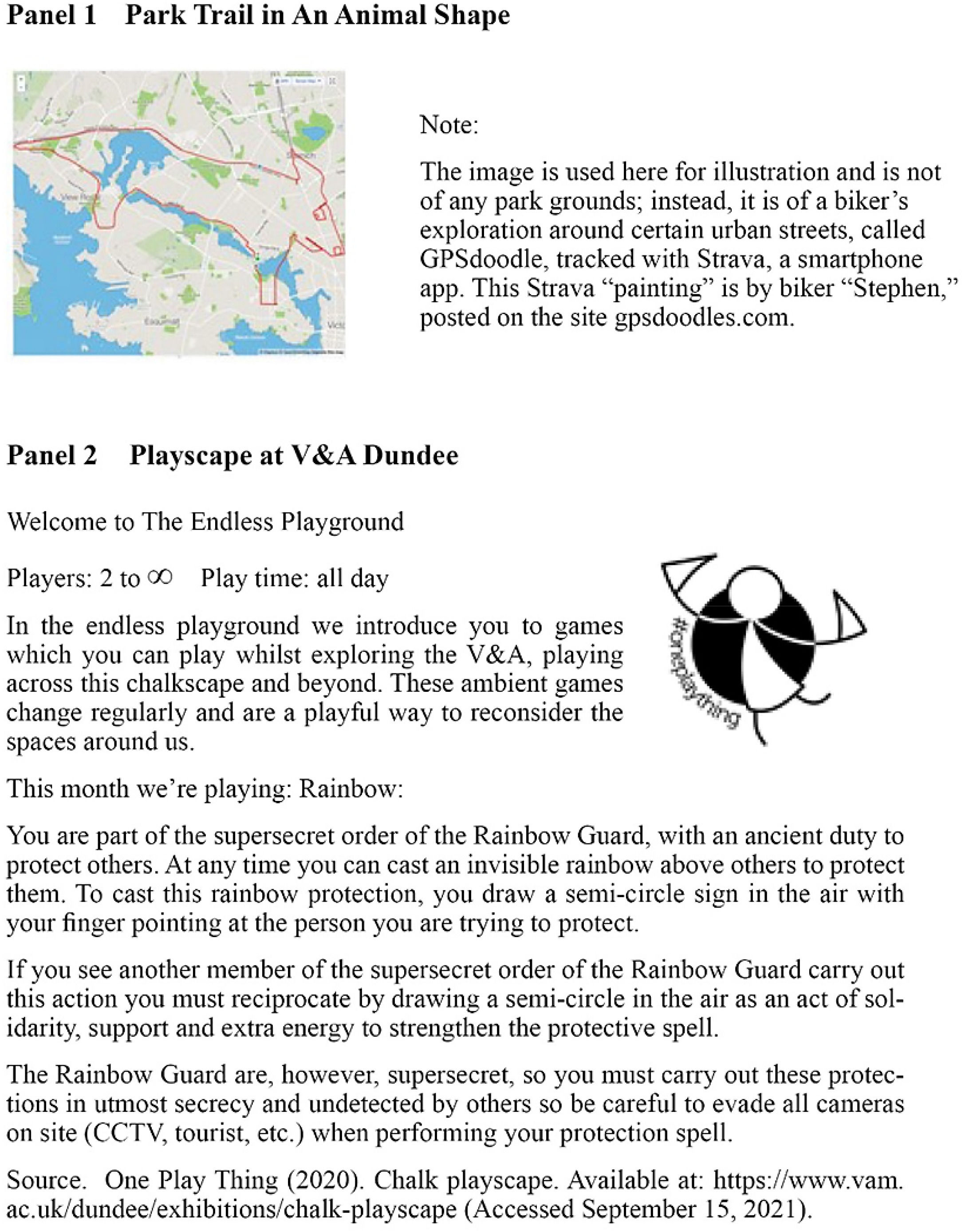

The health benefits of walking (even strolling) receive documentation based on science (see Healthline.com 2018). The very existence of neighborhood parks brings people out to enjoy the outdoors and get some exercise. Higher and more intensive use of parks for walking can be motivated by making the walking trails more fun, for example, by installing “fun facts” display panels along the path or carving the trail in the shape of an animal. Where possible, trails could be built as webs of paths combining multiple animals for walkers to discover individual animal shapes. This latter idea is akin to some bikers’ urban explorations with path tracking using the GPS app Strava (see Exhibit 1, Panel 1). Park and recreation agencies may also build interactive play installations, temporary or permanent, that engage groups of people in creative arts and “ambient play acts”—playful body movements in tandem with friends or other bystanders to convey a sentiment or to enact a storyline. An interesting example is the playscapes created at V&A Dundee, Scotland's first design museum (One Play Thing, 2020). See Exhibit 1, Panel 2.

In the context of urban streets, such installations and projects are viewed by scholars as promoting social wellbeing and a sense of community (Innocent and Stevens, 2021). These installations encourage exploration, spontaneous playful acts, and social interactions (Daly et al., 2020). This concept of ‘urban play projects” can be applied even more potently in neighborhood parks. For instance, webs of trails can be used for group- or team-based competitive sports, challenging visitors to discover and complete one of the “animal trails” within a maze of trails. Parks could also stage fitness events and then expand the reach of these events multifold by livestreaming for the city's residents at large. According to one survey of 879 park visitors from 42 states, consumers will continue to demand or welcome virtual broadcasting of park events (Bhatt, 2020). The Scotland survey (NatureScot, 2020) found levels of participation in nature focused activities increased significantly during lockdown–many relaxed in their gardens (62%), took part in gardening (42%), enjoyed wildlife in their gardens (36%) and enjoyed watching wildlife from indoors through a window (30%).

Community Projects for Collective GoodThe neighborhood events can be staged on a bigger scale to bring people together citywide, and for “build something” activities. The Qualtrics national survey showed a rise in altruism and community sensitivity during Covid-19 in a segment of the public. This sensitivity arose due to empathy felt toward the unfortunate members and also a feeling of interdependence in keeping each other safe in a pandemic (World Happiness Report, 2021). One researcher has pointed out an additional source: walking. “One of the few positive impacts of the pandemic has been a renewed connection with local neighborhoods and community–largely through the simple act of walking” (Franks, 2020). In the ongoing pandemic, this habit of walking needs channeling to sustain and thrive, by modifications in urban streets and distributed network of pocket parks mentioned earlier. In managing these pocket gardens and neighborhood parks, local governments could well reduce their maintenance burdens by co-opting local residents as volunteers for park maintenance projects such as cleaning and mulching. Other community projects such as city beautification projects, paint- a-town or paint-a-neighborhood projects, community gardens, etc., that bring community members together in collaborative activities can spark a new enthusiasm for community building. Of these, community gardens deserve special attention.

The food supply chain interruption and the resulting food insecurity were the first casualties, especially among the urban poor. According to Feeding America, more than 54 million people in the country had experienced food insecurity (FeedingAmerica.org). Clearly, the need to improve food distribution networks is urgent, especially with better funding and resourcing of and coordination among not-profit local food supply organizations (Bublitz et al., 2021). Self-sufficiency in local food production will be another leg of the solution. Community gardens partially alleviated this hardship on the urban poor, as demonstrated in cities from London to Manila to Amsterdam to New York, where local managers of community garden groups sprung to action (Schoen & Blythe, 2020; Wharton, 2020). Beyond meeting the need for fresh produce for the urban poor and other city residents, these gardens served as hubs of social support and community engagement (Publichealth.columbia.edu, 2021).

Community gardens have multiple benefits: (a) fresh and organic produce, (b) reduction of carbon footprint both due to organic nature of farming and reduction in transportation, (c) health benefits from fresh food and due to physical activity, and (d) mental health benefits from leisure in green ambiance—“horticulture therapy,” so to speak, and (e) most importantly, community building through collaborative work (National Garden Scheme, 2021).

DiscussionPropositions for future researchThe emergent perspectives and recommended urban innovations are summarized as propositions in Table 1. These emergent perspectives can be empirically tested by survey research. Sample measurement items for each would be these: 1. Rise in altruism: Since COVID-19, I want to do more to help people in need; 2. Growth in community-mindedness: I now seek to connect with my community more than before; and I value our planet's health now more; 3. Valuing health and financial security more: I am very motivated to protect my health; and I want to make sure I will have saved enough money for the future; 4. Seeking work-life balance: To me, my family time and personal time is as important as work; and 5. Increased engagement with nature: I want to now spend more time in nature than I did before COVID. It will be useful to track these sentiments over time.

Summary of Propositions on Perspectives and Urban Innovations

| A. Propositions on the Emergent PerspectivesWith the experience of the pandemic and lockdowns:A small and yet significant segment of the population has cultivated a mindset of increased altruism.A segment of the population has become more community oriented.A significant proportion of people have become more motivated to protect their health and to secure their financial future.A significant proportion of people will seek greater work-life balance in the post-COVID world.A significant proportion of people will value nature more and will seek opportunities to engage with nature more.B. Recommendations for Urban InnovationsTo respond to the emergent new perspectives among the population, urban governments and social agencies must consider the following innovations:Make neighborhoods as connected communities again, with opportunities for social interactions and staying in touch with nature.Governments may incentivize the industry for bringing more ecology-friendly products to people, and urban, local governments may encourage small businesses and entrepreneurs to develop a cottage industry and the local “maker economy.”City managers should invest in green public transportation and also create green spaces in urban hubs.Parks and recreation agencies should expand their footprint, and within these parks and other public spaces organize activities for fitness and socialization, especially in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods.Local public and social agencies should organize more community projects that may bring people together in productive projects such as community gardens, city beautification, and food kitchens. |

For urban innovations, urban planners will need to create blueprints and generate a slate of options (e.g., how many new parks, of what size, with what amenities, and at what locations). They will also need to assess the prospective utilization by local populations as preferences are likely to differ by neighborhoods and by cities and towns (Dudley et al., 2015). Many of these projects will be long-term, of course, but so as to not lose the momentum of current public sentiment, urban planners should think up and implement some small-scale and low investment projects in relatively short order, such as creating green spaces and starting a few community gardens.

Research LimitationsThe study is limited by both data and its theorizing approach. On data, we did not undertake a large-scale survey of the population to map their mindsets. Absent this resource, we relied on a small dataset (N=550) with Qualtrics national population that had measured people's evolving sentiments in a broad-brush way. That said, the entire world setting provided a natural field experiment in which we lived and thus we studied this setting as “participant observers.” We relied on our informal observations of our socio-cultural milieu in our own cities. Most importantly, our reflections benefited from published reports and commentaries both in the academic journals and in journalism media.

Correspondingly, our research could not employ a quantitative-data based hypothesis-testing method. Instead, we pursued the reflective-inductive method of theorizing. This method is necessarily interpretative-intuitive and is limited by the subjective reflections of the authors. At the same time, as scholars have commented, such reflective-inductive methods have the potential of generating ideas and propositions that transcend the bounds of tangible data. In particular, the empiricist-deductive methods are well-suited more to “linear theories”—where phenomenon are linear cause-effect variables. In contrast, inductive-reflective method are better suited to understand a pattern of multiple forces creating a phenomenon and then to identify categories that organize the multi-faceted phenomenon (Delbridge & Fiss, 2013; Rothchild, 2006).

Managerial ImplicationsOur research has implications for both the public at large and for urban mangers. For public, if there were a way of publicizing on mass news media our finding of the emergence of the virtuous mindset among a small segment, this will benefit both this segment and rest of the population. It will benefit this segment by making their own feelings more salient (Lockwood and Kunda, 1999). For the rest of the population, knowledge about what some of their fellow citizens are feeling will likely make them want to internalize and adopt those feelings themselves, not to the same extent and not among all, of course, but among some people and to some significant degree. This is because of the normative influence theory (Yanovitzky & Rimal, 2006; Kincaid, 2004): When people know how others are thinking, they either reinterpret their own feelings or move own thoughts closer to the thoughts of others.

The most potent implications of our research are for urban agency managers. Our urban innovations, derived from our academic reflections, need and will benefit from the experience and formal economic and social-impact assessment by trained urban planners (Freudenburg, 1986; Sairinen, 2004). During the past three years, city and state administrators have been preoccupied with fighting the pandemic. Improvisations in public space reconfiguration have occurred on ad hoc basis, and some as informal projects by volunteer citizens (Maury-Mora et al., 2022; Troya et al., 2020). We offer to city mangers an organized list of five most indicated urban innovations that would channel the emergent perspectives among the citizens for self-improvement as well as for becoming better citizens. By implementing these projects, weighted by their own appraisal, of course, and within the feasibility of their budgets, urban governments can bring about significant public well-being.

Balancing Recovery versus Virtuous PursuitsThe draft blueprint is not intended to cause loss of sight of the first priority for city governments for what “C40” has called “a green and just recovery”—C40 is a group of 40 city leaders from around the world chaired by the Mayor of Los Angeles (C40.org, 2020). That recovery entails “remedying long-running environmental and social injustices for those disproportionately affected by the climate crisis and the pandemic” (C40knowledgehub.org, 2020). Yet, while attending to the critical task of economic, health, and social “recovery” for the disadvantaged populations, urban governments should not let slip by the opportunities for “radical innovations” (Tiberius et al., 2021)—to channel the new-found goodwill for community cohesion in large swaths of the “relatively advantaged” citizenry. The more community involvement projects centered on “do good” activities could be staged, the more it will help all people recover from the pandemic's shock.

Urgent Need to Catalyze: It Is Now, Not LaterTo assume that the heightened salience of virtuous values will be long enduring is naïve. Some citizens will continue to savor them, of course, and preserve and solidify them, with or without any external push. But for many, these will fade away as time passes. If urban management agencies did not offer the means for citizens to implement one or more of the five facets of the newfound virtuous mind, then citizens are not likely to continue to effortfully seek facilities and events to enact and experience those virtues. If public parks agencies do not offer new avenues of outdoor recreation or socializing, and if cities did not offer avenues for community involvement, then these citizen mindsets and desires will likely subside and eventually evaporate. While there is some risk that “you build it, they may not come,” there is also the certainty that “if you don't build it, they cannot come!”

To minimize the downside risk of low patronage, urban planners should build collaborative knowledge about the preferences of resident citizens (Al Omoush et al., 2020). Based on such knowledge, investments in new infrastructure could be prioritized for (a) scalability (e.g., try a small park first); (b) low set-up and low dismantling costs (e.g., local weekly markets and volunteer projects); (c) relieving already visible demand loads (e.g., more bikers seen in cramped lanes); (d) neighborhoods lacking mobility and/or access to essential services (e.g., no bus service, no health clinic nearby); (e) proven success in past projects (e.g., community gardens); (f) catalyzing rather than directly funding capital investment endeavors (e.g., 3D printing by commercial hobby shops); (g) inherent aesthetic value (e.g., greening of sidewalks). Even though the citizens with the pandemic-awakened new “virtuous mindset” likely make up only a niche segment, the ranks of participants in “do good for the community” projects will likely expand due to the “modeling” effect (Bandura, 2021). And many of the urban reimagining projects benefit the residents at large, including the self-focused and the mere spectator. Therefore, it is the opportunity for urban planners and governments and other community organizations to stage these public well-being events as our world reopens.

ConclusionOn the surface, the current public discourse is anything but one of virtue. The politicization of public health mandates, across the world—what some have called the information pandemic (Xie et al., 2020), has given rise to vociferous divisions in our society, where people seem to have banded together in their protests of public health measures. Amidst this noise, it is easy to dismiss the presence of the opposite sentiment: that a segment of the public has used the pandemic experience to rethink their lives and has cultivated a virtuous mindset of leading a more mindful, purposive, altruistic, nature- and community-centered life. Pandemics bring enormous suffering to millions of people, of course, but they also have this essential consequence of causing major societal shifts that alter people's worldviews. In the wake of the Antonine plague (A.D. 165 to 262), Christianity replaced the paganism entirely to become the dominant religion, as Christians showed compassion and caring for all their fellow humans, including the pagans (Latham, 2020). Similar compassion among a swath of the public has flourished during the current pandemic alongside the politically divisive factions, as surveys from diverse nations cited earlier have amply documented.

Surveying a vast body of reports on public's thoughts and behaviors over the past two years aids in identifying this virtuous mindset and organized its description as comprising five facets. The five urban management innovations nurtures this new mindset. Only a mass catastrophe with the reach and scale of a pandemic can produce this seed of a virtuous mindset in a critical niche segment of the public. This study proposes five innovations for urban planners, to modify infrastructure and launch new programs so as to channel and nurture this new mindset. As this study outlines, the third decade of the 21st century provides opportunities for urban agencies to harness silver linings within the ongoing COVID-19 era.

Financial disclosureThis research was facilitated by a sabbatical grant to first author from Northern Kentucky University.

To understand the emergence of the virtuous mindset that we posited, we utilize a slice of data available to us from a national random survey of 550 US adults in the Qualtrics population. The survey was done in May 2020, at the height of COVID-19, and when most of the country had been under lockdowns for at least a month. Done online, the sample (n=550) comprised 51.5% males, with the following age distribution: 25-30, 17.5%; 31-40, 37.6%; 41-55, 32.0%; 56-65, 10.7%, and 65+, 2.2%. In terms of education, 12.4% had middle or high school education; 22.5% had some college; 41.5% were college graduates; and 23.5% had a master's degree. Respondents with <$10K income made up 5.3%; $10 to 30K, 14.2%; $31 to 50K, 16.4%; $51 to 70K, 20.9%; $71 to 100K, 16.2%; income >$101K, 27.1%. Thus, in the sample, adult men and women of all ages, income, and education groups were represented. The survey elicited their agreement or disagreement with a set of statements. Figure A1 presents their responses.

As Figure A1 shows, the survey respondents exhibited remarkable changes in their outlook: 52.0% for mindfulness, 67.7% more considerate, and 84.9% grateful, for example. While their self-ratings of becoming nicer, more considerate, more grateful, and the like could well be over-estimated, these are their subjective perceptions, exactly as they felt them and for that reason valuable. These numerical ratings are corroborated by their textual answers to an open-ended question included in the survey: “How has the pandemic changed your perspective and in the future what will you do differently?” Table A1 presents a sample of their verbatim answers. This is not a representative sample of all the textual responses, and many responses were centered on the sufferings and hardships the respondents were experiencing. The selection in Table A1 is purposive, intended to capture that segment of the public for whom the mindset did change for the positive, and as Figure A1 and Table A1 show, this transformation did occur surely and vividly for a significant segment of people.

Emergence of a Virtuous Mind in a Segment of the Public

| Everything is changed on how we live. This lockdown has provided me time to look forward and think what I need to achieve in the future. (M 25-30, professional, CA) | Yes, to be safer the freedoms we had last summer are long gone. However, we should come close together as a community. (M 31-40, food server, FL) |

| It made me realize how much money I spent on unnecessary things. I will never look at life the same again, I will continue to spend less, relax more, and take better care of myself. Spend more time with family, devote more time to community (W, 56-65, travel agent, TX) | Definitely take my health more seriously. Give my work life balance more priority. (F, 41-55, clerical, CA) |

| Yes, I think life is short so I will be more careful I will try to keep myself healthy. (M, 25-30, developer, CA) | I have realized that life is too short to waste time not doing what I truly love. I will live every day to the fullest. (F, 31-40, photographer, FL) |

| It has made me realize what is most important which is my relationship with God and my family. (M, 41-55, RN, CA) | I will be so grateful to see my family and friends again. This had made me grateful for family and friends. (F, 41-55, disabled, FL) |

| I'll look at life from a different perspective. Life is short. We should just try to appreciate what we have. (M, 31-40, CEO, NY) | I will donate to charities more often because now I understand the pain that people suffer. (M, 25-30, pizza chef, NY) |

| My perspective is that we need a lot of change in the world to make things less awful. (M, 25-30, artist, OH) | Yes, I would eat healthier foods, exercise more, love more, communicate more and appreciate more. (M, 31-40, banker, GA) |

| I will learn to slow time and enjoy life more. Spend more time with family and friends making memories and not overcommitting ourselves. (F, 41-55, administrator, WV) | I would like to get closer to God, … and put a lot of effort into maintaining good relationships with my loved ones. (F, 56-65, call center agent, OH) |

| I look at life as vanity, death could come at any time it wants to. (M, 31-40, construction executive, IL) | I will try to lead the best life, help anyone, anytime I can, focus more on family and friends than on wealth. I will try to keep this feeling in me for a long-term change so it will become a habit and finally my lifestyle. (M, 31-40, senior manager, CA) |

| I will be more concerned about my health, I would have to treat people with respect, … I would make better use of my time and I will attend more religious activities. (M, 25-30, IT manager, CA) | Appreciate the little things a lot more, spend time with the ones you love, check on your neighbors, let them know you care. (F, 41-55, nanny, TN) |

| I have felt very blessed personally by the chance to catch up on things. Before this life was far too hectic and stressful. This has allowed me to slow down and get things done with more balance on my life between work, home responsibilities, and free time. (F, 41-55, KG teacher, FL) | Being a kinder person. Reflecting on my actions and words more. (M, 31-40, hospitality worker, CO) |

| M=man, W=woman (self-identified) | |

| From a national random survey of US adults, May 2020. |

Banwari Mittal holds an MBA from IIMA and a Ph.D. in marketing from the University of Pittsburgh. A professor of marketing, Mittal has taught at SUNY, Buffalo, the University of Miami, the University of New South Wales (Sydney, Australia), and Northern Kentucky University (current affiliation). His research has been published in such journals as Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of Retailing, Journal of Economic Psychology, Psychology & Marketing, and Marketing Theory. He has served as Associate Editor for Journal of Business Research. He has coauthored seven books: ValueSpace (McGraw-Hill 2001, www.myvaluespace.com), Customer Behavior (with Jagdish Sheth, Dryden Press, 1998, and Thomson Learning, 2002), and “MY CB Book” (with Jill Avery, Robert Kozinets, Priya Raghubir, and Arch Woodside; www.mycbbook.com, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2021): 50 Faces of Happy (2020), TCBC—Teaching Consumer Behavior with Cases (2021), Consumer Psychology—A Modernistic Explanation (2021), and Voices from Behind the Mask—Remembering How We Felt As the Lockdowns Began (2021).

Arch G. Woodside is Professor of Marketing (Retired), Boston College. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Advances in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research and Advances in Business Marketing and Purchasing annual book series (Emerald Publishing). He is the former Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science (2017-2020, Taylor & Francis Publishers) and the former Editor in Chief, Journal of Business Research (1976-2016, Elsevier Publishing). He is a Fellow of Divisions 8 and 23, American Psychological Association, Royal Society of Canada, Society for Marketing Advances, International Academy for the Study of Tourism, Global Academy of Innovation and Knowledge, and Global Alliance of Marketing and Management Associations. He is Past-President of the Society of Consumer Psychology (Division 23, APA). He completed the PhD in Business Administration, Pennsylvania State University, 1968. He was awarded the Honoris Doctoris, University of Montreal, 2013 and Doctor of Letters, Kent State University, 2015. His recent books include The Complexity Turn (2017), Springer Publishing; Bad to Good: Achieving High Quality and Impact in Your Research (2016), Emerald Publishing; Case Study Research: Core Skills in Using 15 Genres, 2nd Edition (2016), Emerald Publishing; Storytelling-Case Archetype Decoding and Assignment Manual (SCADAM) (2016) with co-author Suresh Sood, UTS, Emerald Publishing; Incompetency and Competency Training: Improving Executive Skills in Sensemaking, Framing Choices, and Making Choices (2016) with co-authors R. De Villiers, AUT, and Roger Marshall, AUT (Emerald Publishing).

![Ideas for Nurturing Playfulness in Public spaces [Panel 1. Park Trail in An Animal Shape Panel 2. Playscape as V&A Dundee] Ideas for Nurturing Playfulness in Public spaces [Panel 1. Park Trail in An Animal Shape Panel 2. Playscape as V&A Dundee]](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/2444569X/0000000700000003/v1_202207240530/S2444569X22000579/v1_202207240530/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr3.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)