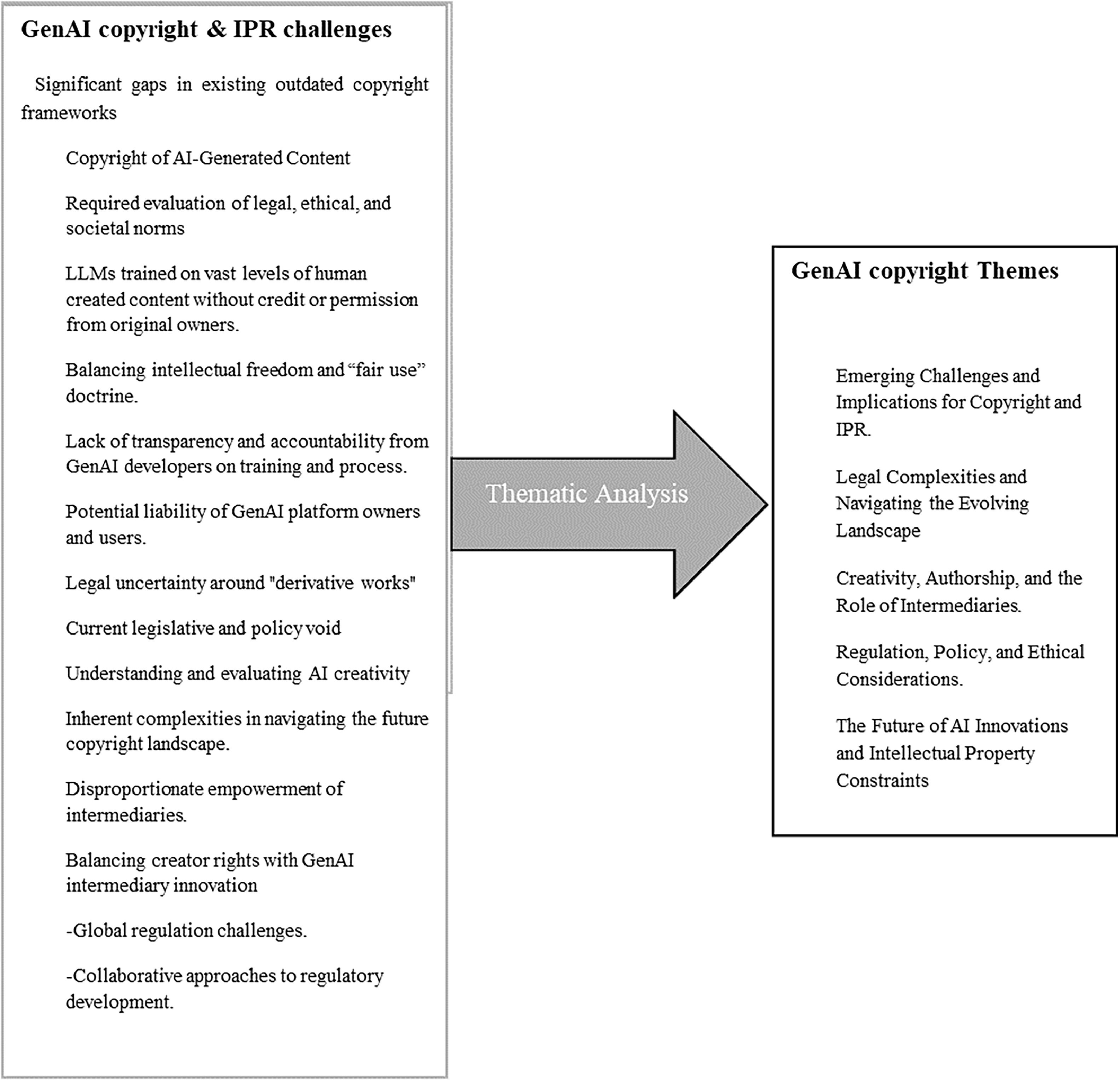

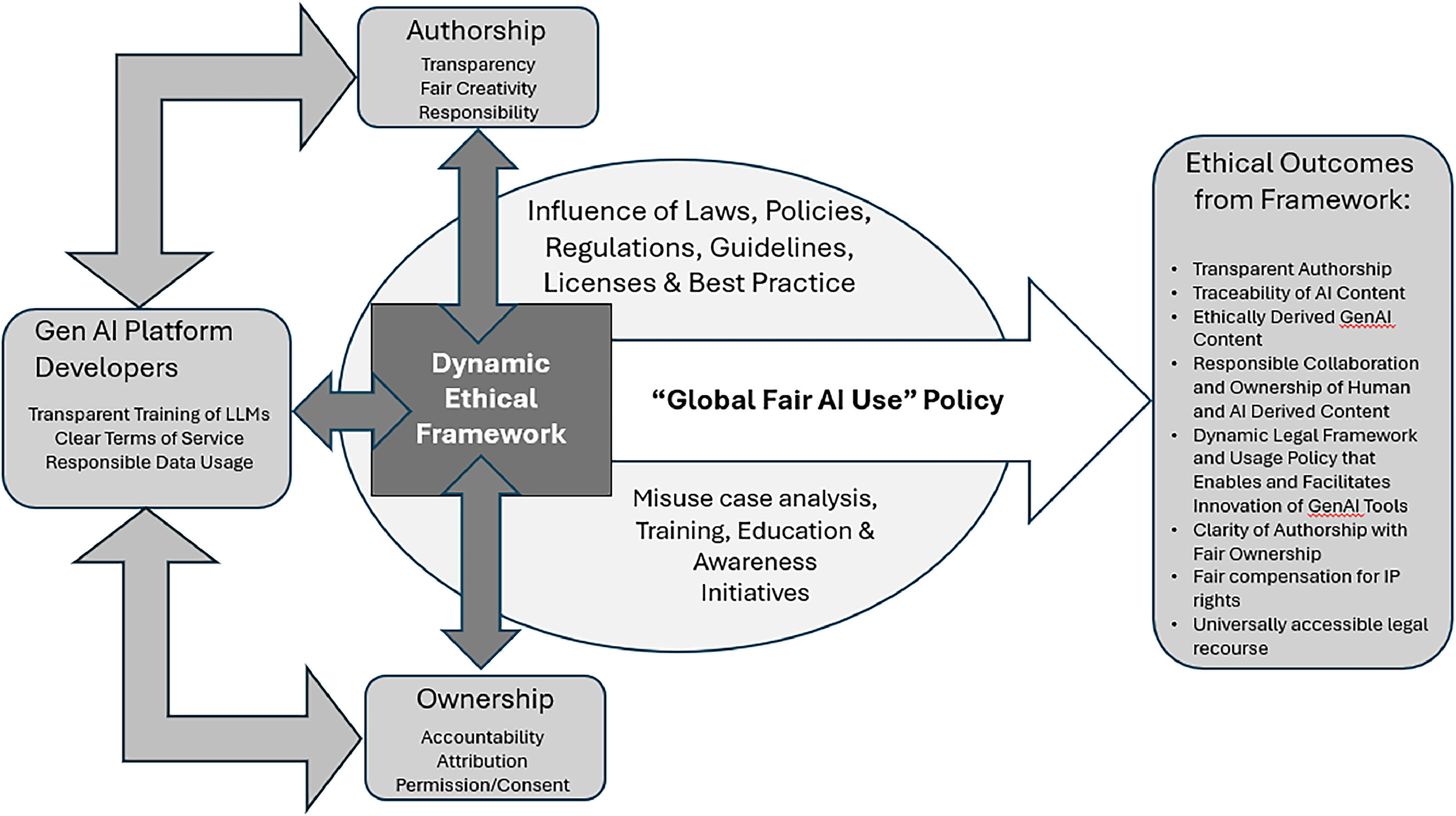

The rapid integration of generative AI (GenAI) into industries and society has prompted a re-evaluation of copyright and intellectual property rights (IPR) frameworks. GenAI's ability to produce original content using data from human-created sources raises critical ethical and legal concerns. Current copyright and IPR frameworks, designed around human authorship, are insufficient to address these challenges. This study, using a multi-perspective approach, explores GenAI's disruptive potential in replicating or transforming copyrighted materials, challenging established IPR norms. Findings highlight gaps in legislation and the opacity of GenAI platforms. To address these issues, this study presents a Dynamic Ethical Framework linked to a future global fair use policy, aiming to guide responsible GenAI development and use. By incorporating insights from domain experts, this study contextualizes emerging challenges and potential solutions within broader societal and technological trends. That said, this study calls for international collaboration and further research to reform IPR related laws and frameworks, ensuring they remain relevant and equitable in a GenAI-driven era.

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) utilises machine learning and deep learning technologies, employing algorithms such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and transformer models to create new content based on user prompts (Dwivedi et al., 2023). Open AI's ChatGPT was launched in November 2022 and quickly reached 100 million users, becoming the fastest-adopted consumer application in history (Hu et al., 2023). OpenAI's Generative Pre-Transformer (GPT) models are trained on vast datasets to produce content that is often indistinguishable from that created by humans and has the potential to revolutionise how work is undertaken across industries and business functions (MIT Technology Review, 2023). The impact that GenAI will have on global economies is likely to be transformational with estimates between US$2.6 and $4.4 trillion of value added to the global economy each year, thereby increasing the total economic impact of AI by 40% (McKinsey & Company, 2023). It is predicted that AI will automate half of all work between 2040 and 2060, and that the impact of GenAI will accelerate this progress, a decade earlier than previous estimates (MIT Technology Review, 2023). The capabilities of GenAI to create new content in the form of text, images, software, and now with the advent of OpenAI's Sora, the ability to create video from text-based input, is nothing short of staggering. GenAI tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini and Bing AI - utilise Large Language Models (LLMs) that have been trained on billions of diverse data sources and parameters including: internet data, academic journals, books and news articles (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Lucchi, 2023). However, confusion exists on the detailed process and legality of the LLM training process, due to the minimal levels of transparency and accountability from GenAI providers. This has profound legal and ethical consequences related to the protection of human creativity, authorship, and content ownership (Frosio, 2024).

The training of LLMs and widespread use of GenAI has revealed a set of complex and evolving legal challenges surrounding the use of GenAI technologies, particularly concerning copyright and the notion of authorship (Bonadio et al., 2022a; Salami, 2021). Copyright is a specific type of intellectual property that protects original authorship, such as literary, artistic, musical, and other creative works. Copyright grants the creator exclusive rights to use, distribute, and modify their work, typically for a limited period. Intellectual property rights (IPR) refers to the broad set of legal rights that protect human creation such as artistic works, inventions, designs and images (Hugenholtz & Quintais, 2021). Although copyright laws cover direct copies of pixels, text and software, the imitation content developed by GenAI, is based on LLMs effectively trained by digesting and utilising the original copyrighted data, somewhat negating the “AI generated” new content claim (Dwivedi et al., 2023). The emergence of AI as a non-human creator, directly challenges the existing legal infrastructure built around the human creator (Frosio, 2024; Liu et al., 2023). This presents a number of complexities - for example in a scenario where an artist utilises a GenAI tool to create a digital artwork, the AI produces the artwork based on the styles and influences from LLM trained copyrighted works. The original artist could claim copyright over the AI generated works arguing that their original artwork was used, whereas the digital artist and GenAI platform could perhaps argue that the AI output is derivative work. These issues have led some artists and content creators to initiate legal action against organisations such as Stable Diffusion and also Midjourney in the Getty case, over improper use of 12 million licenced photos (Reuters, 2023). Claims of software piracy have been made against OpenAI and Microsoft over the creation of Copilot - now integrated into MS Office 360 (Jo, 2023; Kahveci, 2023). Researchers have emphasised the misinformed narrative of purely AI-generated work and the fact that it does not currently exist, there is always a human creator in the loop somewhere, and the concept of AI-generated work is overly simplistic and potentially misleading, acting as a disservice to those seeking to experiment creatively with GenAI systems (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Fenwick & Jurcys, 2023; Lim, 2023).

The Wall Street Journal's interview with OpenAI's Chief Technology Officer (CTO) - Mira Murat in March 2024, on OpenAI's latest AI image generation system Sora, highlighted concerns about the potential misuse of copyrighted work to train AI models and the lack of transparency from OpenAI regarding its data practices. The responses from the OpenAI CTO led many commentators to question whether the organisation has adequately safeguarded the rights of content owners and creators (Wall Street Journal, 2024). The “arms race” for developing AI products has demonstrated questionable adherence to IPR with Meta admitting to using both Instagram and Facebook content to train its Llama 2 LLM based model. These practices and the potential for big tech companies such as Alphabet with its access to huge levels of Google controlled internet data, to utilise the vast data resources at their disposal, raising significant ethical concerns relating to consent and copyright of user data during the training of LLMs (Business Insider, 2024).

The existing legal system is being asked to adjudicate on the bounds of what constitutes “derivative works” (an essential element of the creation process building on existing works and creating something new and innovative) and the interpretation of fair use doctrine, which allows copyrighted work to be used without the creators permission for: commentary, criticism, teaching and research use; the outcome of which is a profound destabilisation of copyright law (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2024; Appel et al., 2023; Crawford & Schultz, 2024; Gans, 2024; Jodha & Bera, 2023). The absence of a traditional mechanism of authorship in AI-generated content creation, could potentially shift the economic benefits away from human creators towards those who own or operate the AI technologies and platforms (Israhadi, 2023). This shift could significantly impact the livelihoods of artists, writers, and other creators, potentially leading to economic disparities and a devaluation of human creativity (Crawford & Schultz, 2024; Dwivedi et al., 2023). Balancing the transformational technological advances now possible with GenAI together with the preservation of content creators’ rights to compensation, is critical to navigating the copyright landscape in this new era (Lee et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2023; Lucchi, 2023).

Whilst a limited number of studies have sought to shed light on the implications for copyright and IPR from the widespread use and adoption of GenAI (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Fenwick & Jurcys, 2023; Lucchi, 2023; Zhong et al., 2023), this emerging research area is somewhat lacking a deeper analysis of the multitude of complexities facing content creators and policy makers. We assert that by developing a multi-contributor perspective on the critical aspects of GenAI, copyright and IPR, we create valuable new insight and the establishment of a new research approach and research agenda. This study, therefore, aims to conduct a detailed examination of the various challenges posed by GenAI. We advocate for a proactive, informed, debate and research agenda relating to copyright law and intellectual property with an appeal to move from engaged to generative scholarship that takes into account misuse case analysis for prospective theorisation. We posit that this approach can develop much needed focus on values and creativity of the human in the loop to ethically and responsibly navigate within this complex landscape.

The remainder of this study is organised as follows. The next section outlines the approach to the study and examines the impact this research style has had on the development of literature on emerging phenomena and its influence on policy. Section 3 presents the individual expert contributions that cover the range of perspectives and insights to this subject. The Discussion is outlined in section 4 where we discuss the key themes from the contributions and present the Dynamic Ethical framework. The paper is concluded in the final section.

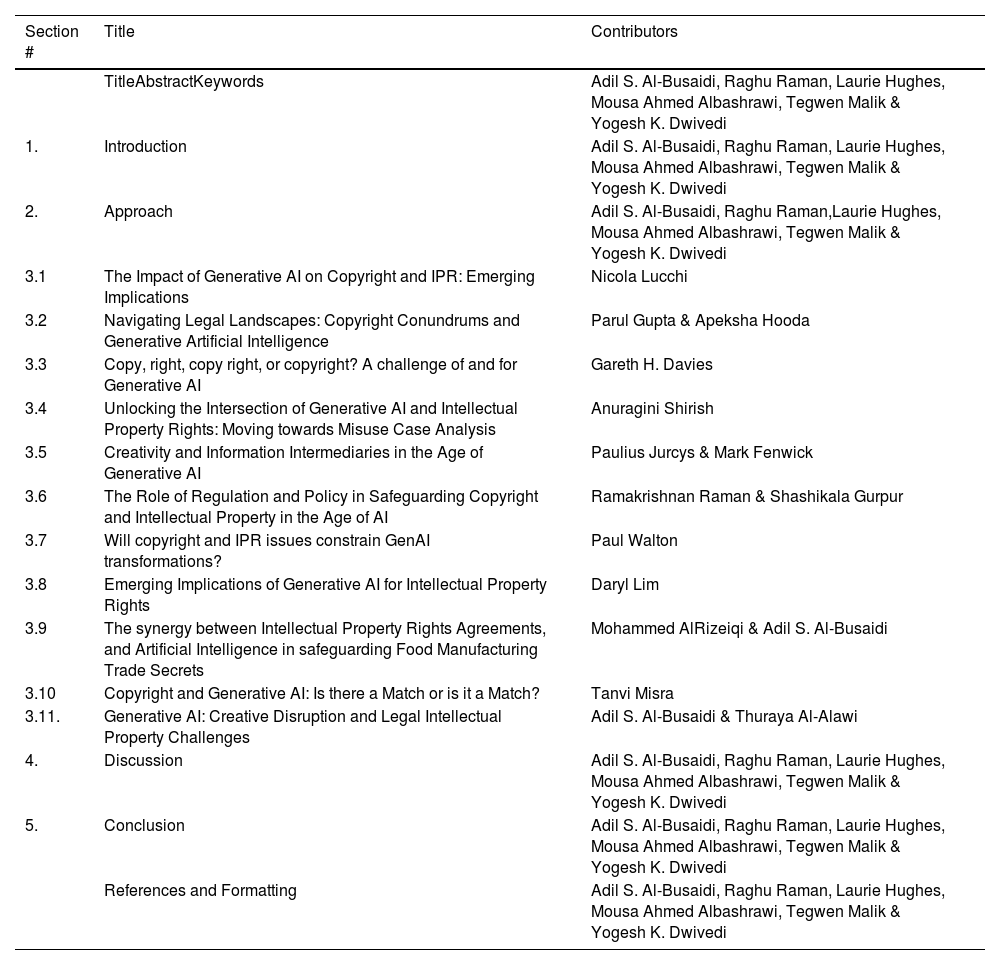

ApproachThis study is consistent with prior research that employs a multi-perspective expert-based approach, initially proposed by von Foerster (2003) and subsequently developed by Dwivedi et al., (2024; 2023; 2021). This method concentrates on gathering valuable insights from authoritative contributors on cutting-edge research themes. This study invited specialists from both academia and practice to discuss the critical issues related to GenAI and its impact on copyright and intellectual property rights (See Table 1 for the list of contributions included in this study). Each contribution offers distinct insights and viewpoints, reflecting their dual expertise in academia and/or practice. This collaborative approach offers valuable insight, especially when the topic at hand has been minimally explored within the existing literature or is an emerging issue that has yet to be thoroughly explored within the extant research. Previous research that has adopted this approach, namely Dwivedi et al., (2023), has achieved notable recognition and policy impact, with citations from entities such as the European Union, Joint Research Centre, European Commission, and The Policy Institute (PlumX Metrics, 2024). This underscores the significant impact and broad scope of adopting a multi-expert perspective. Earlier studies using this approach have been widely referenced, helping to shape research agendas on diverse topics such as AI, Smart Cities, Digital Marketing, the Metaverse, and impacts of Covid19, while also expanding the discourse to a broader audience.

Contributors and section titles.

| Section # | Title | Contributors |

|---|---|---|

| TitleAbstractKeywords | Adil S. Al-Busaidi, Raghu Raman, Laurie Hughes, Mousa Ahmed Albashrawi, Tegwen Malik & Yogesh K. Dwivedi | |

| 1. | Introduction | Adil S. Al-Busaidi, Raghu Raman, Laurie Hughes, Mousa Ahmed Albashrawi, Tegwen Malik & Yogesh K. Dwivedi |

| 2. | Approach | Adil S. Al-Busaidi, Raghu Raman,Laurie Hughes, Mousa Ahmed Albashrawi, Tegwen Malik & Yogesh K. Dwivedi |

| 3.1 | The Impact of Generative AI on Copyright and IPR: Emerging Implications | Nicola Lucchi |

| 3.2 | Navigating Legal Landscapes: Copyright Conundrums and Generative Artificial Intelligence | Parul Gupta & Apeksha Hooda |

| 3.3 | Copy, right, copy right, or copyright? A challenge of and for Generative AI | Gareth H. Davies |

| 3.4 | Unlocking the Intersection of Generative AI and Intellectual Property Rights: Moving towards Misuse Case Analysis | Anuragini Shirish |

| 3.5 | Creativity and Information Intermediaries in the Age of Generative AI | Paulius Jurcys & Mark Fenwick |

| 3.6 | The Role of Regulation and Policy in Safeguarding Copyright and Intellectual Property in the Age of AI | Ramakrishnan Raman & Shashikala Gurpur |

| 3.7 | Will copyright and IPR issues constrain GenAI transformations? | Paul Walton |

| 3.8 | Emerging Implications of Generative AI for Intellectual Property Rights | Daryl Lim |

| 3.9 | The synergy between Intellectual Property Rights Agreements, and Artificial Intelligence in safeguarding Food Manufacturing Trade Secrets | Mohammed AlRizeiqi & Adil S. Al-Busaidi |

| 3.10 | Copyright and Generative AI: Is there a Match or is it a Match? | Tanvi Misra |

| 3.11. | Generative AI: Creative Disruption and Legal Intellectual Property Challenges | Adil S. Al-Busaidi & Thuraya Al-Alawi |

| 4. | Discussion | Adil S. Al-Busaidi, Raghu Raman, Laurie Hughes, Mousa Ahmed Albashrawi, Tegwen Malik & Yogesh K. Dwivedi |

| 5. | Conclusion | Adil S. Al-Busaidi, Raghu Raman, Laurie Hughes, Mousa Ahmed Albashrawi, Tegwen Malik & Yogesh K. Dwivedi |

| References and Formatting | Adil S. Al-Busaidi, Raghu Raman, Laurie Hughes, Mousa Ahmed Albashrawi, Tegwen Malik & Yogesh K. Dwivedi |

Whilst the multi-expert format could be criticised for an element of overlapping narratives across perspectives, we maintain that the preservation of the unique emphasis of each contributor enriches the overall narrative. Another limitation of the multi-contributor format is the length of the paper. However, this study has limited the contributions to eleven due to the specialised nature of this emerging topic. We argue that the encouraging further debate and discussion on the fast-evolving topic of GenAI and its impact on copyright and IPR is important, and by compiling diverse opinions and perspectives into a single document we provide a valuable resource for readers to compare and contrast a range of views and perspectives. We recommend that readers engage with the paper selectively, focusing on segments that resonate most with their interests and the range of broader themes within the paper. Having listed the sections and their contributors in Table 1, the numbering and section/topic headings are subsequently used in the remaining sections of this paper.

Expert ContributionsThe intricate relationship between generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) and copyright, as well as intellectual property rights (IPR), constitutes a complex and rapidly evolving field of inquiry. This section presents individual contributions,1 as listed in Table 1, that offer alternative perspectives on this emerging phenomenon.

The Impact of Generative AI on Copyright and IPR: Emerging Implications - Nicola LucchiIntroductionIn the era of synthetic creativity, the rapid advancement of GenAI technologies poses unprecedented challenges and opportunities for copyright and other IPRs (Laukyte and Lucchi, 2022). As AI's capabilities extend into the realms of creating complex, original content, from written works to visual arts, the traditional boundaries of copyright law and intellectual property are being redefined. This transformation necessitates a re-evaluation of legal, ethical, and societal norms governing creativity, ownership, and the sharing of intellectual goods (Bonadio et al., 2022a).

The socioeconomic model underpinning GenAI is characterized by two principal features: its dependency on human-generated content, provided without financial compensation, and its aversion to regulatory oversight by public authorities (Lucchi, 2023; Strowel, 2023). This aversion goes beyond traditional private-government interactions, fuelled by shared beliefs about the values of emerging technologies. Despite being based on assumptions that are increasingly recognized as obsolete and misleading, these perceptions persist with the tenacity of long-held habits.

AI systems universally rely on machine learning algorithms, which necessitate vast quantities of data for effective training and subsequent performance optimization (Goldberg, 2017; Lucchi, 2023). From a legal perspective, it is noteworthy that most of this data comes from individuals’ creative work, for which they receive no compensation (Epstein et al., 2023). Furthermore, the acquisition of this data often occurs without obtaining the legally prescribed consent from the copyright holders, which is a critical consideration (Bonadio & McDonagh, 2020; Dornis, 2021; Lucchi, 2023; Senftleben & Buijtelaar, 2020). Given the substantial economic value derived from such data, this situation raises significant ethical and legal concerns. It also presents a paradox where the very essence of a shared digital economy—data—is generously given away, often without a second thought to the potential for financial recompense. Addressing this imbalance requires a nuanced dialogue that extends beyond the scope of this short article. However, it is imperative to acknowledge the role of individual data providers in powering the advancement of AI technologies, and the overlooked potential for compensatory mechanisms to ensure equitable benefit sharing (Geiger and Iaia, 2024).

The Evolution of Creativity in the Age of AIThe rise of GenAI technologies, such as GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer),2 Gemini,3 Grok,4 and DALL-E,5 has blurred the lines between human and machine creativity (Bonadio & McDonagh, 2020; Buccafusco, 2016; Dornis, 2020; Ginsburg & Budiardjo, 2019; Guadamuz, 2017; Lucchi, 2023; Mezei, 2023; Sobel, 2017). These AI models can generate textual content, images, and even music that rival the quality of human-produced works, raising profound questions about the nature of creativity and the definition of authorship. The ability of AI to draw from vast datasets of existing works to produce new creations challenges the very foundation of copyright laws built on the concept of human authorship and originality. Yet, we stand at the dawn of this technological revolution with recent advancements, such as multimodal AI systems that seamlessly integrate text, images, and videos, and diffusion models capable of generating hyper-realistic content, reveal the potential for even more sophisticated and intricate forms of machine creativity. These innovations not only expand the boundaries of AI's creative capabilities but also amplify the legal and ethical complexities surrounding intellectual property in ways we are just beginning to grasp.

Legal Challenges and Jurisdictional PerspectivesThe advent of AI-generated content has exposed gaps in existing copyright frameworks, which traditionally recognize only human authors. One of the primary legal challenges is determining the ownership and copyrightability of AI-generated works. The Berne Convention, along with various global copyright norms, does not mandate that works must be authored by humans. However, numerous jurisdictions, including those in the European Union and the United States, underscore the necessity for a human creator behind a copyrightable work. Furthermore, the structure of copyright law is predominantly oriented towards a human-centric perspective. This is highlighted by the Berne Convention's stipulation that the copyright term extends beyond the lifetime of the author for an additional number of years after their death.6 Such a regulation inherently assumes the author's mortality, thus implying human authorship. Jurisdictions around the world grapple with these questions, offering varied responses. For instance, the United States’ copyright law does not currently recognize non-human creators, leaving AI-generated works in a sort of legal limbo.7 Similarly, the approach to copyright within the European Union reveals a nuanced comprehension of AI's contributions, highlighting the necessity for a work to embody the author's “intellectual production” and distinct creative expression to fulfil the criterion of originality.8 This perspective underscores the challenges faced in reconciling AI authorship and creativity model within the framework of copyright law.

Intellectual Property Rights in the Age of Machine LearningAs previously noted, GenAI technologies rely heavily on existing data, including copyrighted materials, to train their algorithms. This practice has sparked debates on the legality and ethics of using copyrighted works to train AI systems without the explicit permission of copyright holders.9 The unresolved question of whether AI-generated works are derivative or wholly original under the law creates uncertainty for creators, users, and AI developers alike. GenAI systems, which include technologies capable of producing art or generating textual content, predominantly utilize vast repositories of human-created data for their training processes. This reliance on pre-existing content generates legal concerns under the current copyright laws. A notable dilemma pertains to the heterogeneous nature of the datasets utilized. While a segment of these datasets comprises content that is informational in nature and not limited by copyright constraints, a considerable portion probably embodies copyrighted materials. This phenomenon is starkly observable in the realms of text processing, facial recognition, and image recognition training datasets, where copyrighted content is frequently incorporated. Such practices invariably solicit legal scrutiny concerning the conditions under which copyrighted materials may be utilized legitimately.

In the United States, the doctrine of fair use introduces a degree of flexibility, allowing limited exploitation of copyrighted materials for specified purposes, including criticism, commentary, research, or teaching purposes.10 In particular, in the domain of AI development and the collection of data for its training, the fair use doctrine under section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act can play a significant role, traditionally protecting economically important endeavours, as demonstrated by the landmark case of the Google Books project.11 However, its application to the data utilized for AI training awaits more definitive interpretation through future and ongoing case law (Sobel, 2017).12 Despite the potential for broad application, this legal flexibility is circumscribed, with the current absence of explicit guidelines fostering a climate of uncertainty among both AI developers and content creators.

In contrast, the European Union law delineates two distinct exemptions for Text and Data Mining (TDM) :13 the first is specifically designed to support research and innovation within a non-commercial context, and the second, more broad-based exemption, applies to various purposes, provided rights holders have not explicitly prohibited such use.

In particular, the first exemption facilitates the mining of copyrighted content by researchers and entities for scientific research and innovation purposes, without the necessity for explicit consent from copyright holders, contingent upon fulfilment of specific conditions.14 This legislative provision significantly benefits academic and research institutions, empowering them to dissect large data volumes in previously unfeasible manners, thus expediting scientific advancements and innovative breakthroughs. The second, broader exemption applies to any party engaging in such activities with legally accessed works, extending beyond scientific research purposes.15 This exemption allows rights holders to opt out by explicitly reserving their rights. They can do so in a recognizable format, which includes machine-readable indicators for publicly accessible online content, metadata, and the terms and conditions of a website or service. Furthermore, the recently approved EU AI Act stipulates that creators of GenAI systems must devise a compliance strategy with EU copyright laws.16 This entails employing sophisticated technology to acknowledge and adhere to copyright notices. Hence, AI developers are mandated to ensure their systems respect copyright protections by recognizing and abiding by the stipulations set forth by rights owners. This directive ostensibly aims to equip creators with the necessary insights to discern the use of their works as training data, thereby facilitating an informed decision regarding the reservation of their rights for TDM purposes. However, despite the European regulatory framework appearing clearer, in reality, it introduces complexities and stringent conditions that challenge the breadth of permissible use of copyrighted materials (Margoni and Kretschmer, 2022; Senftleben, 2022). This paradoxically creates a scenario where – amid the facade of clarity – the practical application of these rules demands careful navigation to avoid infringement, potentially stifling innovation by limiting access to vital data for AI development and other creative endeavours.

Adapting Copyright and IP in the AI EraIn this evolving landscape, a pressing task emerges for stakeholders. Adapting copyright and IP in the AI era requires lawmakers and policymakers to confront a nuanced challenge: finding a balanced approach. Such balance must protect the rights of intellectual property holders while also nurturing the fertile ground of AI innovation. The rigidity of current copyright laws could choke the growth of GenAI technologies, yet too lenient a stance may leave human creators unprotected and their intellectual contributions undervalued. This delicate balance requires a comprehensive understanding of the technological, legal, and ethical dimensions of AI and creativity.

Recognizing the limitations of current legal frameworks, there is a growing consensus on the need for new paradigms that accommodate the realities of AI-generated content and, more broadly, the emerging ‘synthetic society’ (van der Sloot, 2024). It is this evolving concept of a “synthetic society” that invites us to reconsider traditional notions of creativity and ownership. As AI systems become integral to cultural production, frameworks like joint human-AI authorship or statutory licenses for AI training may become pivotal. Envisioning a future where AI and human creators collaborate seamlessly, the challenge lies in crafting legal norms that not only protect individual contributions but also nurture an ecosystem where innovation and cultural heritage coalesce harmoniously. Proposals include identifying a form of joint authorship between AI developers and human operators, creating new categories of copyright specifically for AI-generated works, and developing international standards to harmonize copyright laws in the age of AI (Bonadio et al., 2022b; Salami, 2021). The consideration of joint authorship between AI developers and human operators, along with the creation of new copyright categories for AI-generated works, appears to be a logical step forward. It acknowledges the collaborative nature of AI-generated content and the blurred lines between human and machine contributions to creative processes. These efforts aim to ensure that copyright and IPR evolve to reflect the changing landscape of creativity and innovation. Regarding the legitimate use of copyright-protected works to train AI systems, there are – for example – proposals to introduce a statutory license for machine learning or an AI levy within copyright law in order to compensate human authors for market share and income losses due to the substitution by GenAI in creative fields (Geiger and Iaia, 2024; Senftleben, 2023). This approach seeks a balance, fostering AI innovation while acknowledging human creators’ contributions. It is rooted in balancing fundamental rights, suggesting a way to compensate creators fairly for their works used in AI training. This idea aligns with evolving copyright laws to support AI's role in creativity and innovation, ensuring creators are rewarded also in this new AI-driven context.

ConclusionAs GenAI continues to reshape the landscape of copyright and IPR, it becomes increasingly clear that existing legal frameworks are ill-equipped to address the complexities of AI-driven creativity. The path forward requires a comprehensive re-evaluation of copyright law and intellectual property rights, with an eye towards fostering innovation while protecting the rights of creators also in this new AI-driven age. This endeavour is not solely the purview of legal professionals but a collective societal task that calls for dialogue, collaboration, and innovative thinking. As we navigate this uncharted territory, the goal must be to create a legal and ethical framework that supports the dynamic interplay between human creativity and AI, ensuring that the AI-powered future is one where technology serves to enhance, not diminish, our shared cultural heritage and intellectual achievements.

Navigating Legal Landscapes: Copyright Conundrums and Generative Artificial Intelligence - Parul Gupta & Apeksha HoodaIntroductionOne hundred million users by the end of two months after launch made Chatbot ChatGPT, a prototype GenAI, one of the fastest-adopted consumer applications. ChatGPT was launched by in November 2022 by OpenAI, a company backed by Microsoft (Hu et al., 2023). While TickTok took nine months to reach this milestone and Instagram reached there in two and a half years after launch, ChatGPT became the fastest-growing technology innovation by acquiring 100 million users in just two months (Chow, 2023). ChatGPT is just one example of GenAI applications which has a built-in algorithm to facilitate continuous learning from input data and future decision-making that may be independent or directed by the user. GenAI applications are capable of generating text, audio, video, synthetic data or even codes (Gordijn & Have, 2023). While GenAI's growing popularity is attributable to its simple user interphase and ease of use, its capability to provide indistinguishable content from human-created content reflects its potential to have significantly large macroeconomic and social effects (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Ooi et al., 2023). According to a recent report by Goldman Sachs (2023) it is expected that in the next ten years, GenAI would boost productivity growth by 15% and would drive a $7 trillion increase in global GDP. Business firms from a large range of industries are showing increasing interest in GenAI applications spanning from early use cases in IT automation, digital labour etc. to specialized core areas of business (Kanbach et al., 2024). For example, healthcare companies are increasing adopting GPT4 for analysing patients’ health, medication and check-up records and drafting responses to patients’ queries. Another prominent presence of GenAI can be witnessed in the marketing and advertising industry where applications such as Performance Max suite are being used to enhance the efficiency of marketing and advertising campaigns. In general, GenAI applications have transformed a large number of business functions (Ooi et al., 2023).

While GenAI has tremendously improved the efficiency and productivity of businesses, it has also drawn significant criticism due to its profound legal and ethical implications for both business and society at large. This process adopted by GenAI applications for self-learning, decision-making and generating output while responding to users’ request has been questioned for its legality, particularly regarding the potential infringement of copyrights owned by input creators. This concern stands out as one of the most commonly reported legal issues (Kucukali, 2022). Numerous lawsuits filed against GenAI applications worldwide have raised pertinent legal questions regarding copyright infringements. For example, could GenAI applications use or reuse public repositories of texts, codes, images etc. without giving credit to its creators and taking permission from its creators, in certain cases where permission was necessary? Should this usage be treated as an infringement of the copyrights of the original creators? And the final question is who should be held liable if the output of GenAI infringes the copyrights in the existing works- the platform or the user?

It is crucial to understand the legal risks associated with GenAI applications, particularly in relation to copyrights, before businesses fully embrace the benefits they offer. In the subsequent sections, we delve into legal aspects of copyrights in the original works, and legal complexities surrounding GenAI applications and its copyright conundrums.

Mechanics of GenAI and its Copyright ConundrumsGenAI is an advanced form of artificial intelligence that is capable of generating new content such as audio, video and text etc. indistinguishable from human-created material (Appel et al., 2023; World Economic Forum, 2024). GenAI achieves this by employing well-tested neural networks across vast datasets to uncover underlying patterns and relationships. A noteworthy feature of GenAI is its capacity for self-learning through both supervised and unsupervised training methods. The mechanics of GenAI applications such as ChatGPT can be divided into four broad stages (Pavlik, 2023; Peck, 2023): Firstly, there's pre-training, where the GenAI is trained on extensive datasets. Following this, the model undergoes the transformer architecture stage, where transformers utilize self-attention mechanisms to evaluate the significance of each word or pixel in generating the output. Transformers serve as the cornerstone of GenAI models. Subsequently, the model can be fine-tuned on specific datasets or images relevant to the task at hand, such as text or image generation. Once fine-tuning is complete, the GenAI generates output based on user prompts, assigning probabilities to each word or pixel in its vocabulary or image repository. The output generation occurs iteratively, with each word or pixel influencing the prediction of the next.

In summary, GenAI models operate by harnessing deep learning to generate outputs based on learned patterns during pre-training and fine-tuning stages, utilizing publicly available data. However, the legal implications of this methodology have raised concerns, particularly regarding potential copyright infringement (World Economic Forum, 2024). Questions are raised in the court of law whether the use of data by GenAI applications for pre-training or fine-tuning constitutes copyright infringement. Should liability arise, who bears responsibility—the GenAI platform owner or the user who initiated the query? These questions underscore the complexities surrounding copyright and accountability in the age of GenAI.

Deciphering Legal Liabilities of Generative Artificial Intelligence Systems in Copyright InfringementThe above discussion highlights two primary forms of copyright infringement in existing works involving; firstly, when GenAI uses or makes copies of the existing works for self-training and secondly, when GenAI output closely resembles with those existing works. As legal disputes over alleged copyright infringements by GenAI applications continue to rise, policymakers and courts worldwide have begun to scrutinize the self-training processes and outputs generated by GenAI applications within the context of existing legal frameworks for copyrights protection.

Although law is a subject of land and the specifics of legal provisions may differ between countries, copyright protection laws universally prohibit the reproduction of entire or significant portions of copyrighted works. For instance, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA), a United States copyright law, affords extensive legal protection to the rights of original creators, encompassing artistic, literary, and digital content. It prohibits distribution, reproduction, public display, construction of derivative works, and circumvention of technological measures employed by creators of original works (U.S. Copyright Office Summary, 1998). Similarly, the Copyright Act of 1957 in India encompasses a broad spectrum of works, ranging from artistic creations to open-source computer code and cinematographic films, under its ambit17 (Copyright Office, Government of India). In addition to safeguarding the exclusive rights of creators, legal protections extend to moral rights such as attribution and integrity of the work. In the European Union (EU) member states, creators of original works enjoy exclusive rights to distribute, reproduce, perform, display, and create derivative works for either the lifetime of the creator or a fixed duration if the creator is a legal entity. Moral rights, including the right to be acknowledged as the original creator and to object to derogatory treatment of their work, are inherent in the definition and scope of copyrights (Hutukka, 2023).18 While the range of protected creative works and activities forbidden to the non-owners is quite extensive in copyright laws across the countries, most incorporate exceptions allowing for limited fair use of copyrighted works. The fair use doctrine allows the use of copyrighted material without the permission of the owner for a transformative purpose in a manner for which it was unintended. Under this principle original works can be used without creators’ permission for the purposes such as news reporting, scholarships, criticism, teaching and research and comments (Appel et al., 2023).

Legal ComplexitiesFrom an in-depth review of copyright laws, it is evident that copyright laws across countries provide two broad technological measures; those aimed at preventing unauthorized access to the original works of creators and those designed to prohibit unauthorized copying or utilization of the original work to produce similar works. Within the current legal frameworks, GenAI applications may be liable for copyright infringement if they both had access to the original works and GenAI generated output is substantially similar to the original works (Zirpoli, 2023). It is noteworthy that courts have recognized circumstantial evidence, such as access to the original works, as sufficient to establish a case of "copying from the original works." For instance, proof of access may be demonstrated by evidence indicating that the underlying works were publicly available and that the GenAI platform was trained using those works to generate outputs. Although, the test for “substantially similarity with the underlying work/s” is complex, leading relevant cases have defined it in terms of both “qualitative and quantitative significance of the copied portion in the questioned work compared to underlying work/s as a whole (Lucchi, 2023).

In the context of GenAI, the test of “substantial similarity” may require no less than original underlying work/s where an ordinary common man would not be able to differentiate between the original work and GenAI generated work (Lemley, 2023). However, there is no significant agreement as to how likely it is that GenAI platforms may generate a substantially similar output. Defending the allegations of copyright infringement, OpenAI recently argued that a well-designed GenAI program typically avoids copying significant portions or unaltered data from a specific work during training or output generation. Therefore, any “substantial similarity with a particular original work” is a highly unlikely accidental outcome (Appel et al., 2023). On the other hand, in another lawsuit it was alleged19 that the images produced by a GenAI system called Stable Diffusion were highly similar to and derivative of the original images. The original creators of the image claimed that the methodology used to determine the similarity underestimated the true rate of copying from the original images (David, 2023).

In addition to the discussions surrounding "substantial similarity tests," a critical question arises: who bears responsibility if a GenAI system violates copyright in original works—the platform owner or the user? According to prevailing legal principles, both parties could potentially be liable. For instance, if a user is directly responsible for using a GenAI platform to gain unauthorized access to original works, reproduce them, or generate substantially similar works, the platform owner could face potential liability under the "vicarious infringement doctrine" for failing to oversee the infringing activity on its platform. This liability stems from the platform owner's ability to supervise activities on its platform and its direct financial interest in those activities (Zirpoli, 2023). One noteworthy complication here is that user might not be aware of the work that was copied or reproduced in response to his/her prompt. Moreover, the user did not have direct access to the original work in question. Consequently, within existing legal frameworks, it becomes challenging to determine whether the user, the GenAI platform owner, or both should potentially be held liable for copyright infringement.

Concluding Remarks and Directions for Future ResearchIt is evident from the above discussion that existing legal frameworks for copyright protection lack clarity and agreements on establishing potential legal liability for copyright infringements by GenAI applications. Litigations in various jurisdictions bring to light several pertinent issues within the context of GenAI applications and copyright infringements, such as the definition of "derivative works," the criteria for determining "similarity with the existing works," and the interpretation of the fair use doctrine, among others (Lucchi, 2023). Historically, clashes between technological advancements and copyright laws have arisen, with some technology companies successfully defending against allegations of copyright infringement. For instance, Alphabet successfully defended its Google search engine from the legal liability for using text from copyrighted books. The court of law accepted Google's argument that transformative use under the fair use doctrine allowed for the scrapping of text from books to develop the Google search engine (Appel et al., 2023). However, past judgments may not serve as direct precedents for disputes involving potential copyright infringements by GenAI applications due to the unique complexities involved. We invite future studies to examine the complexities and provide insights into application and scope of fair use doctrine” in the context of GenAI applications.

Recent legal battles, such as the Warhol Foundation versus Lynn Goldsmith case,20 shed light on crucial considerations, particularly regarding the "similarity test" and the determination of a work's transformative nature under fair use. For example, the recent judgment of the apex court of the U. S. in a legal battle between Warhol foundation and Lynn Goldsmith can be useful to understand when a new piece of work passes the “similarity test” and gets the status of “transformative piece of work” under the fair use doctrine. The court in the instant case held that original works like those of other photographers were protected by copyright laws even against the famous artists. The protected rights included the derivative works that transformed the original works. It was further stated in the judgment that the fair use argument might not prevail if the use had a purpose and character which was not sufficiently distinct from the original work (Mangan & Drinkwine, 2023). Future research should focus on how the outcomes of ongoing litigations influence legal interpretations concerning the potential liability of GenAI platform owners and users for copyright infringements. Clarity on these matters is increasingly urgent, given the widespread adoption of GenAI applications for both creative and non-creative purposes.

The prevailing uncertainty poses significant challenges for businesses utilizing or considering leveraging GenAI applications. Failure to ensure that derivative works generated by GenAI applications fall within the parameters of the fair use doctrine and GenAI output is not “substantially similar to existing works" may expose businesses to penalties for copyright infringements, whether intentional or inadvertent. The legal complexities and lack of clarity within existing frameworks impede the optimal realization of GenAI applications' transformative potential in business operations. Future scholarly research should aim to investigate legal solutions that address the existing ambiguity and complexities surrounding copyright issues in GenAI, including the fair use doctrine and the "substantial similarity test."

Copy, Right, Copy Right, or copyright? A challenge of and for Generative AI - Gareth H. DaviesIntroduction“Congress shall have the power… to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries”.

When the above was written into the United States Constitution providing the basis for copyright protection across a new nation, the authors likely gave little thought to the prospect of machines being the authors and inventors. Since then, technology has raced ahead as GenAI puts us in a position where the law is catching up with the concept of machines as originators of new material, while we are already working with such output.

Modern legislators in jurisdictions around the world are trying to grapple with the regulation challenges from GenAI, but without governments missing out on the opportunities for improved productivity and the new sectors created by such a paradigm shift. Most recently, the debate surrounding GenAI has become prominent as ChatGPT presents a tipping point for its application (Teubner et al., 2023).

Not only in writings, GenAI has also advanced in fields such as musical composition, from conceptual (De Mantaras & Arcos, 2002) to commercial (Drott, 2021). Recorded music alone represents a global annual market worth $26bn, with particular growth in Asia and emerging economies.21 Understanding the provenance, the process of generation, and the ownership of such material is therefore key in determining the rights and revenues of works. This begs questions, not readily resolved, even in the ‘real’ world. For example, a recent dispute involving the singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran involved studio recordings and notes being used to evidence the originality of his work. This shows that even the natural creativity ‘black box’ is sometimes challenged to show the origins of its creations (Komlos, 2021; Bosher, 2022).

Amongst challenges of potential bias, privacy infringement, and misuse, there are the questions of whether GenAI infringes others’ existing rights and/or creates new ones (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Fui-Hoon Nah et al., 2023; Lucchi, 2023). Much like real intelligence, the artificial is limited by the quality and extent of its prior knowledge, making the provenance of training data a key question (Dwivedi et al., 2023). Questions of copyright relating to the materials entered into the black box as training sources, are being tested in the courts (Samuelson, 2023; Peres et al., 2023) and are to be determined before arriving at the further question of ownership of output. While some argue the output could simply be considered as being for the public domain (Palace, 2019), there is a need for clarity in order to advance AI use. It therefore remains that resolving the challenges of copyright sits amongst the five critical areas for research in use of AI (Van Dis et al., 2023).

Historical Context of Technology and CopyrightSince the Statute of Anne in 1710, copyright had been entwined with challenges posed by technology, since the printing press through to recordable digital media, and of course the Internet.22 The printing press ushered in government controls over this disruptive technology, focusing on restricting the reproduction and diffusion of material. At first, this was to secure government control in managing the information available to the population. This may resonate with modern concerns over GenAI use for electoral interference, such as to create malign deep fakes of political messaging. However, earlier focus has shifted to development of the printers’ business models and the interests of authors. In turn, an economy was created around intellectual property rights, moving beyond established production factors of land, capital, and physical labour.

More recently, a similar debate has emerged around using the vast data available through the Internet to create news feeds, with data-scraping search tools creating questions about technology re-presenting copyrighted material. In parallel, Google Books, displaying portions of copyrighted material verbatim, presented further questions over copyright infringement. However, it was legally determined that such re-production was not sufficiently ‘substantial’ to be of issue (Sag, 2018).

Debate has often focused on how existing regulations fit with a new disruptive technology. Recently, the fair use or similar consideration of processing copyrighted material for training GenAI has been supported by scholars in the US (Sag, 2018), though notably remains the subject of discussion (Henderson et al., 2023). As the original notion of fair use related to non-commercial application, this becomes stretched as GenAI enters widespread commercial use (Teubner et al., 2023;Henderson et al., 2023).

Around the WorldThe Berne Convention (Ricketson et al., 2022) provides almost global protection for authors, with rights to their works recognised beyond borders. However, prevailing consideration is to only recognise humans’ creations as benefiting from copyright, as reflected in recent rulings affirming this position (Peres et al., 2023). Despite this, some academics have credited ChatGPT as a co-author, noting that GenAI has contributed to their works (Stokel-Walker, 2023). This may be to simply garner interest, to hedge their bets if the machines do indeed rise against us at some point, or more likely to satisfy publishers' requirements (Stokel-Walker, 2023).

A useful early summary of copyright in an emerging AI age was provided by Gaudamuz (2017) for the World Intellectual Property Office, in response to the emergence of AI-generated literary and artistic creations, along with Google exploration of AI to author news articles. This preceded the recent post-pandemic emergence of ChatGPT-driven interest in GenAI and a host of other AI applications. Governments worldwide have been prompted to accelerate their work on related regulation, including copyright legislation, albeit lagging behind the technology's progress.

United StatesAs noted earlier, the US Constitution presented the clear intention for economic benefit from monopolies over intellectual produce. Even subsequent emphasis on freedom of speech enshrined in the First Amendment has not curtailed development of copyright protections. However, US copyright remains focused on human creativity, and “the fruits of intellectual labor” noting these “are founded in the creative powers of the mind” (Gaudamuz, 2017). While claims over GenAI output might therefore be questionable, there is also the issue of potential infringement of what it uses to learn. The US fair use doctrine provides a level of cover, though with consideration needed, including the extent to which inputs are transformed – i.e. dissimilar to the input(s) (Henderson et al., 2023; Lee et al., 2024; Samuelson, 2023). While technology may be more adept at processing vast amounts of information, it begs the question whether something is ‘copied’ becoming a higher bar than that put to human authors – leading back to the Ed Sheeran example.

ChinaEvolution of Intellectual Property Rights protection, specifically Copyright, and how it has mirrored its history in the US is described by Yu (2003). Alford (1995) had also described how Chinese copyright development reflected the original UK state-control of political messaging, alongside the more commercial purpose. In a shift from ‘world factory’ to pursuing technology leadership in Artificial Intelligence, China has major entities such as Huawei, Alibaba and Tencent, accompanied by evolving government oversight and regulation (Roberts et al., 2023; Lundvall & Rikap, 2022).

The question of whether AI or only humans can provide the ‘intellectual achievement’ required by Chinese copyright law is discussed by Wan and Lu (2021), citing differing conclusions from Chinese courts. As China's role in the global technology market progresses, how this aligns with broader regulation will become of significant importance (Roberts et al., 2021).

United KingdomThe UK had been at the forefront of copyright legislation since the Statue of Anne, responding to the emergence of the printing press. This was initially to restrict distribution of material undesirable to the government of the time, rather than to protect or incentivise authorship. It did point towards a relationship between authors’ rights, business models, and technology. Two centuries later, the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act (1988) was forward-thinking in giving consideration to ‘computer-generated’ works, crediting the person who made the ‘arrangements necessary for the creation’. However, this could not have foreseen the breadth, depth and context of creation through GenAI.

While there may be acknowledgement of technology as an originator, questions remain to be resolved. Ongoing efforts to develop a government code of practice on copyright and AI are being met by legislators pushing against the free mining of third party copyrighted materials, which looks to put limits on use of training data (HoC, 2023). It is also notable that despite Brexit, there is consideration of UK regulators looking to work closely with their EU counterparts on this challenging shared issue (Matthews, 2024).

European UnionIn an EU context, some argue that the emerging approach to regulation of Text and Data Mining (TDM) positions copyright law as a potential obstacle rather than an enabler for the learning required by commercial GenAI (Rosati, 2019). The EU has been working to develop rules for ‘trustworthy’ AI within its Artificial Intelligence Act23 (European Union Artificial Intelligence Act, 2024), including the requirement for provision of summaries of copyrighted materials used in AI training.

A tension exists between the pursuit of digital technology leadership, where previous technologies (e.g. Internet search and social media) have been captured by US firms, while protecting broader citizen interests. De Gregorio (2021) describes the shift from the laissez-faire permission offered to internet providers encouraging innovation, through to the more rights-based protection offered by the approach to privacy in the General Data Protection Regulation. Internet services had been let off from responsibility over potential copyright infringements in what they host, while greater responsibility may be required of AI technology. Achieving these dual ambitions is therefore a central challenge for future legislation and regulation.

Rules for the Arms RaceNatural creativity draws upon learnings and experiences, lost in the real neural networks of the mind that are themselves not fully understood. Therefore, it may seem unfair to hold the artificial to a greater expectation, demanding to unpick the origins and workings of its creations. However, work such as that of Vyas et al., and Barak (2023) provides encouragement that GenAI is not sampling and thereby infringing material from which it learns. This supports the fair use rationale for AI to be afforded intellectual freedom, while Henderson (2023 et al., (2023) urges caution.

Meanwhile, the role of the people as well as technology needs focus. Roberts et al., (2023) call for public engagement in the development of policy, while Stokel-Walker (2023) describes how publishers require transparency and responsibility amongst authors. This sits alongside the public good of democratisation of knowledge and its exploitation, akin to the revolution seen with the internet as information became more accessible. As such, the purpose remains for Intellectual Property Rights to seek the balance of public interest, including to incentivise creators. In turn, it provides a social science rather than a technology question, as Samuelson (2023) stresses the importance for researchers to take part in this debate in order to realise fit for purpose legislation and regulation.

The unresolved issues of GenAI and copyright lead to the need for further research and subsequent policy development and legislation, including for protections around fair use (Henderson et al., 2023). Other technological phenomena already pose associated challenges with which the law is still catching up. Regulation of social media remains a live issue, including where it transcends nations. This creates a problem space not only for researchers, but for practitioners and legislators around the world. As Lucchi (2023) suggests, there is even scope to consider whether an entirely new approach to copyright may be needed, as disruptive as GenAI itself – though would Artificial Intelligence be conflicted if it were to come up with its own answer?

Being first in regulating and thereby resolving these challenges may appear like a goal to secure the spoils of GenAI. However, ‘winning the regulation race’, as Smuha (2021) describes, is perhaps not about being first to legislate, but is instead about achieving an outcome of conformity and interoperable market access - a destination best arrived at together.

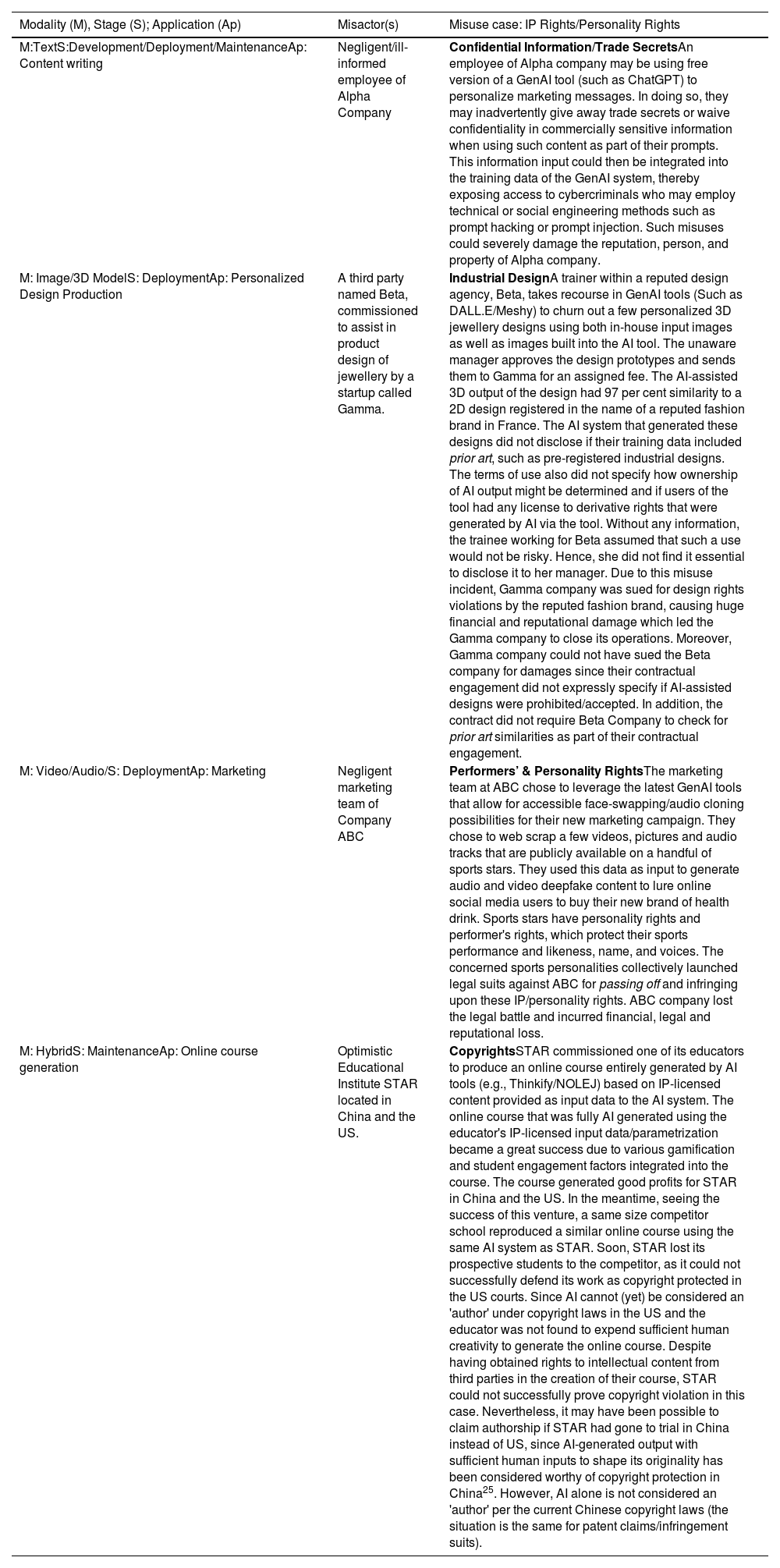

Unlocking the Intersection of Generative AI and Intellectual Property Rights: Moving Towards Misuse Case Analysis - Anuragini ShirishDemocratization and widespread use of GenAI tools such as ChatGPT, Claude, Mid Journey, DALL.E, Microsoft Copilot, etc., by citizens, professionals, creators, consumers, businesses, customers, and employees has led policymakers, legislators, researchers, and the business community to proactively analyse use cases as a way to understand this emerging phenomenon better (Chandra et al., 2022; Deloitte, 2024; Houde et al., 2020; Stohr et al., 2024). Use case analysis can bridge the commonly experienced information asymmetry problem between researchers and industry, which impedes researchers from effectively intervening and contributing through engaged scholarship that can promptly address societal challenges and advance knowledge boundaries. Use case analysis might also give researchers clarity and structure to an inadequately defined phenomenon. It can also pave the way to conceptualization and theorization to explain how and why a focal phenomenon may lead to various positive instrumental and humanistic outcomes. With the accessibility of AI misuse case repositories, researchers can be inspired to use projection and prospection types of theorization (Houde et al., 2020) ,24 which will enhance engaged scholarship and also encourage generative scholarship. While an engaged scholar dives deeper into an already known phenomenon, a generative scholar indulges in future-oriented, imagination-focused and values-based prospective theorization (Gümüsay & Reinecke, 2024; Houde et al., 2020; Ochmann et al., 2024). In this editorial piece, I reflect on the utility of "misuse cases" analysis as a valuable approach to prospective theorization in GenAI using a design fiction approach. In particular, I consider how GenAI and intellectual property rights lay the foundations of a responsible research enquiry (Gümüsay & Reinecke, 2024).

Three core terms first need to be defined for this analysis: misuse case, mis-actor, and intellectual property rights. GenAI ‘Misuse case’ is defined as a completed sequence of actions performed by one or many misactor(s) resulting in a loss for the organization or some specific stakeholder (Sindre & Opdahl, 2001). ‘Misactor’, in this context, refers to real/artificial entities (entities) that interact with the GenAI system and initiate (with or without intention) the misuse case (Sindre & Opdahl, 2001). Here, we take the definition for intellectual property (IP) as provided by WIPO, “as creations of the mind, such as inventions, literary and artistic works, designs, symbols, names and images used in commerce” (WIPO, 2024). IP rights are foundational to patents, trademarks, industrial designs, geographical indications, copyrights and related rights (such as performance(er) rights) as well as trade secrets (WIPO, 2024). However, in certain jurisdictions, other sui generis rights such as databases, integrated circuits, fashion design (in France) may also be entitled to property rights. There are also other rights, such as personality rights as well as rights to image and respect for privacy, which are often implicated along with IP rights in misuse cases. Personality rights are similar to property rights, allowing individuals to control the commercial use of their identity, such as name, image, likeness, or other identifier, even after death in some jurisdictions. In Table 2, I construe a few misuse cases at the intersection of GenAI and IP/Personality Rights. The following table describes the AI system, its modality (including text, code, audio, image, video to hybrid), the stage for which the misuse case has implications (development, deployment (use) or maintenance), and the GenAI application context. Finally, I introduce both the ‘Misactor’ initiating the ‘Misuse case’, providing details and linking the misuse case to a specific IP Rights.

GenAI-IP Right Misuse Case Analysis.

| Modality (M), Stage (S); Application (Ap) | Misactor(s) | Misuse case: IP Rights/Personality Rights |

|---|---|---|

| M:TextS:Development/Deployment/MaintenanceAp: Content writing | Negligent/ill-informed employee of Alpha Company | Confidential Information/Trade SecretsAn employee of Alpha company may be using free version of a GenAI tool (such as ChatGPT) to personalize marketing messages. In doing so, they may inadvertently give away trade secrets or waive confidentiality in commercially sensitive information when using such content as part of their prompts. This information input could then be integrated into the training data of the GenAI system, thereby exposing access to cybercriminals who may employ technical or social engineering methods such as prompt hacking or prompt injection. Such misuses could severely damage the reputation, person, and property of Alpha company. |

| M: Image/3D ModelS: DeploymentAp: Personalized Design Production | A third party named Beta, commissioned to assist in product design of jewellery by a startup called Gamma. | Industrial DesignA trainer within a reputed design agency, Beta, takes recourse in GenAI tools (Such as DALL.E/Meshy) to churn out a few personalized 3D jewellery designs using both in-house input images as well as images built into the AI tool. The unaware manager approves the design prototypes and sends them to Gamma for an assigned fee. The AI-assisted 3D output of the design had 97 per cent similarity to a 2D design registered in the name of a reputed fashion brand in France. The AI system that generated these designs did not disclose if their training data included prior art, such as pre-registered industrial designs. The terms of use also did not specify how ownership of AI output might be determined and if users of the tool had any license to derivative rights that were generated by AI via the tool. Without any information, the trainee working for Beta assumed that such a use would not be risky. Hence, she did not find it essential to disclose it to her manager. Due to this misuse incident, Gamma company was sued for design rights violations by the reputed fashion brand, causing huge financial and reputational damage which led the Gamma company to close its operations. Moreover, Gamma company could not have sued the Beta company for damages since their contractual engagement did not expressly specify if AI-assisted designs were prohibited/accepted. In addition, the contract did not require Beta Company to check for prior art similarities as part of their contractual engagement. |

| M: Video/Audio/S: DeploymentAp: Marketing | Negligent marketing team of Company ABC | Performers’ & Personality RightsThe marketing team at ABC chose to leverage the latest GenAI tools that allow for accessible face-swapping/audio cloning possibilities for their new marketing campaign. They chose to web scrap a few videos, pictures and audio tracks that are publicly available on a handful of sports stars. They used this data as input to generate audio and video deepfake content to lure online social media users to buy their new brand of health drink. Sports stars have personality rights and performer's rights, which protect their sports performance and likeness, name, and voices. The concerned sports personalities collectively launched legal suits against ABC for passing off and infringing upon these IP/personality rights. ABC company lost the legal battle and incurred financial, legal and reputational loss. |

| M: HybridS: MaintenanceAp: Online course generation | Optimistic Educational Institute STAR located in China and the US. | CopyrightsSTAR commissioned one of its educators to produce an online course entirely generated by AI tools (e.g., Thinkify/NOLEJ) based on IP-licensed content provided as input data to the AI system. The online course that was fully AI generated using the educator's IP-licensed input data/parametrization became a great success due to various gamification and student engagement factors integrated into the course. The course generated good profits for STAR in China and the US. In the meantime, seeing the success of this venture, a same size competitor school reproduced a similar online course using the same AI system as STAR. Soon, STAR lost its prospective students to the competitor, as it could not successfully defend its work as copyright protected in the US courts. Since AI cannot (yet) be considered an 'author' under copyright laws in the US and the educator was not found to expend sufficient human creativity to generate the online course. Despite having obtained rights to intellectual content from third parties in the creation of their course, STAR could not successfully prove copyright violation in this case. Nevertheless, it may have been possible to claim authorship if STAR had gone to trial in China instead of US, since AI-generated output with sufficient human inputs to shape its originality has been considered worthy of copyright protection in China25. However, AI alone is not considered an 'author' per the current Chinese copyright laws (the situation is the same for patent claims/infringement suits). |

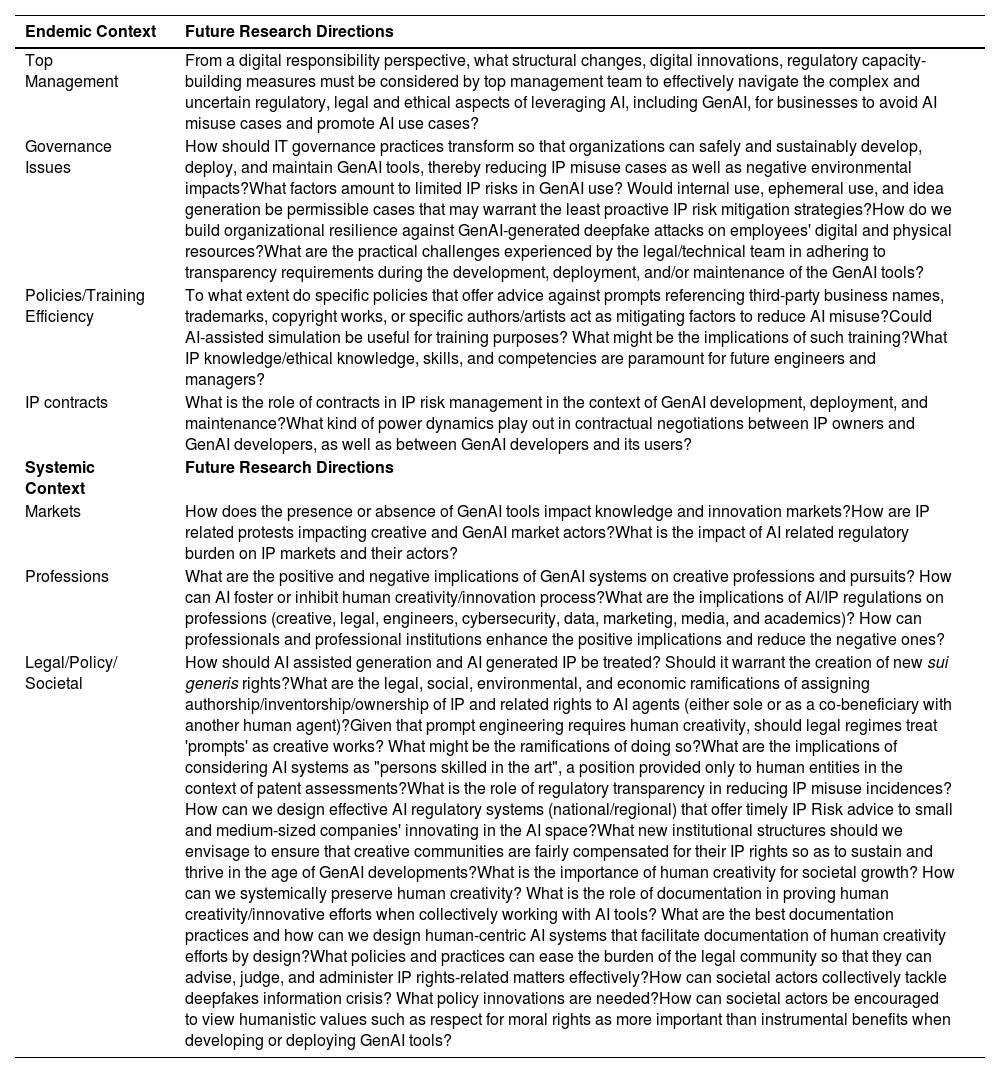

This misuse case analysis provided in Table 2 allows us to look at the murkiness involved in the development, deployment, and maintenance of GenAI applications from the perspective of IP risks. The territoriality of IP rights poses yet another vital impediment to AI-IP risk resilience. Until there are harmonized laws and regulations across different regions, it will be difficult to predict the right course of action regarding GenAI development and deployment concerning IP rights. The recent EU AI act has created an obligation upon the provider of GenAI systems to respect all IP rights and communicate with sufficient transparency details in the training dataset used (European Union, 2024). All AI generated synthetic content (deepfake) must be watermarked before their deployment. In a recent work, we detailed how deepfakes, a GenAI phenomenon, can negatively impact institutions such as states, markets, professions, and communities (Shirish & Komal, 2024). In this work, we provide an in-depth misuse case analysis and argue for the need to consider the whole-of-society approach and indulge in innovative policy design to tackle such wicked problems faced by global societies after comparing the US, UK, India, China, and EU legal provisions. To continue this enquiry on GenAI and regulatory issues, I provide research directions for the endemic and systemic context in Table 3.25

Research directions.

| Endemic Context | Future Research Directions |

|---|---|

| Top Management | From a digital responsibility perspective, what structural changes, digital innovations, regulatory capacity-building measures must be considered by top management team to effectively navigate the complex and uncertain regulatory, legal and ethical aspects of leveraging AI, including GenAI, for businesses to avoid AI misuse cases and promote AI use cases? |

| Governance Issues | How should IT governance practices transform so that organizations can safely and sustainably develop, deploy, and maintain GenAI tools, thereby reducing IP misuse cases as well as negative environmental impacts?What factors amount to limited IP risks in GenAI use? Would internal use, ephemeral use, and idea generation be permissible cases that may warrant the least proactive IP risk mitigation strategies?How do we build organizational resilience against GenAI-generated deepfake attacks on employees' digital and physical resources?What are the practical challenges experienced by the legal/technical team in adhering to transparency requirements during the development, deployment, and/or maintenance of the GenAI tools? |

| Policies/Training Efficiency | To what extent do specific policies that offer advice against prompts referencing third-party business names, trademarks, copyright works, or specific authors/artists act as mitigating factors to reduce AI misuse?Could AI-assisted simulation be useful for training purposes? What might be the implications of such training?What IP knowledge/ethical knowledge, skills, and competencies are paramount for future engineers and managers? |

| IP contracts | What is the role of contracts in IP risk management in the context of GenAI development, deployment, and maintenance?What kind of power dynamics play out in contractual negotiations between IP owners and GenAI developers, as well as between GenAI developers and its users? |

| Systemic Context | Future Research Directions |

| Markets | How does the presence or absence of GenAI tools impact knowledge and innovation markets?How are IP related protests impacting creative and GenAI market actors?What is the impact of AI related regulatory burden on IP markets and their actors? |

| Professions | What are the positive and negative implications of GenAI systems on creative professions and pursuits? How can AI foster or inhibit human creativity/innovation process?What are the implications of AI/IP regulations on professions (creative, legal, engineers, cybersecurity, data, marketing, media, and academics)? How can professionals and professional institutions enhance the positive implications and reduce the negative ones? |

| Legal/Policy/ Societal | How should AI assisted generation and AI generated IP be treated? Should it warrant the creation of new sui generis rights?What are the legal, social, environmental, and economic ramifications of assigning authorship/inventorship/ownership of IP and related rights to AI agents (either sole or as a co-beneficiary with another human agent)?Given that prompt engineering requires human creativity, should legal regimes treat 'prompts' as creative works? What might be the ramifications of doing so?What are the implications of considering AI systems as "persons skilled in the art", a position provided only to human entities in the context of patent assessments?What is the role of regulatory transparency in reducing IP misuse incidences?How can we design effective AI regulatory systems (national/regional) that offer timely IP Risk advice to small and medium-sized companies' innovating in the AI space?What new institutional structures should we envisage to ensure that creative communities are fairly compensated for their IP rights so as to sustain and thrive in the age of GenAI developments?What is the importance of human creativity for societal growth? How can we systemically preserve human creativity? What is the role of documentation in proving human creativity/innovative efforts when collectively working with AI tools? What are the best documentation practices and how can we design human-centric AI systems that facilitate documentation of human creativity efforts by design?What policies and practices can ease the burden of the legal community so that they can advise, judge, and administer IP rights-related matters effectively?How can societal actors collectively tackle deepfakes information crisis? What policy innovations are needed?How can societal actors be encouraged to view humanistic values such as respect for moral rights as more important than instrumental benefits when developing or deploying GenAI tools? |

“AI models are not a vast warehouse of copyrighted material.” - Marc Andreessen

Innovation and creativity primarily rely on the freedom to experiment with new tools available at different times, and across different social, economic, and cultural settings. In this editorial, we pose a provocative question: Are traditional copyright ‘intermediaries’ in the contemporary world now impeding progress and innovation by imposing various restrictions on the experimentation with and utilization of generative AI tools in the creative process?

Fair Use and Generative AICopyright-related issues are at the heart of the debate surrounding GenAI. More specifically, some of the most complex ongoing cases revolve around the legality of using copyrighted material to train GenAI models, and whether AI companies can invoke the fair use doctrine to justify their activities. In the United States, the first factor of the fair use doctrine—the purpose and character of the use—includes two primary considerations: (i) whether the use of the source work is commercial or non-commercial, and (ii) whether the use is transformative.

The “transformativeness” element requires us to address whether the defendant has added new meaning, purpose, or message to the plaintiff's source work. Historical precedents like Sony Betamax, Google Books, and Google's adaptation of Java—a desktop programming language—into a mobile operating system for Android, showcase the potential societal benefits of such transformations.

In the case of GenAI, the transformative impact and added value to society are even more evident. To assess the transformativeness in the age of AI, it becomes crucial to ask: What is the actual value that GenAI delivers to various stakeholders, the broader society, and future generations?

As we stand at the dawn of a new age of GenAI, it may be worth questioning whether the four traditional factors of fair use test are adequate or if we need to introduce new considerations to capture the evolving social contract between humanity and disruptive technologies. Perhaps it is time to move beyond an assessment of transformativeness and consider alternative standards or criteria. At this pivotal moment, should we not also include additional, complementary factors in our evaluation of fair use? If so, it is imperative to discuss what these additional factors might be.

To find answers, we might start by examining the range of stakeholders benefiting from GenAI. Another concept to consider is disruptiveness. The relationship between disruptiveness, innovation and new value appears to be complementary, suggesting that both could play a crucial role in reshaping our understanding of fair use in the age of GenAI.

A New Social Contract with Technology?GenAI is reshaping the entire discussion around copyright, emerging as one of the greatest, yet most misunderstood, ‘gifts’ to humanity. In the following, we suggest that AI serves as a crucial awakening, revealing how we risk being confined by the monopolistic grip of copyright holders and information intermediaries, as well venture capital firms that back the development of GenAI technologies.

There is a pervasive belief that GenAI signals the end of the world—a notion propelled by misinformation or misunderstanding about the potential of AI technologies. Very few technologies have been as heavily burdened with prejudices and misconceptions as AI. The concept of AI has been featured in fiction for over a century, typically culminating in catastrophic endings or dystopian narratives. This persistent story is undoubtedly contributing to the current scepticism. Never before has a technology “arrived” with so much prejudice and semantic baggage.

Can society keep pace with this new technology? It appears not, as our entire infrastructure—economic, cultural and legal—is anchored to outdated models of creativity focused on individual authors, original expressions and exclusive rights that are typically held by powerful intermediaries, such as publishing, record and software companies. These models not only restrict our ability to adapt but also blind us to the possibilities that new technologies such as AI offer. Our models of creativity and the entire infrastructure around creativity are out of sync with the times and are struggling to keep up.

In the current system, virtually no one benefits—a falsehood perpetuated by copyright holders and echoed by the U.S. Copyright Office. This pervasive myth does not serve anyone well. Not only is the legal framework out of touch with today's creative environment, it also contributes to social exclusion, in which creators—artists—are denied new opportunities for creativity.

The problem with the existing copyright framework is that it disproportionately empowers intermediaries—large organizations that own copyrights, such as publishers. These intermediaries propagate the myth that they are protecting creators. However, in many cases, they have appropriated economic rights for themselves and monetized these works to their own advantage, often at the expense of artists and consumers.

How could the emergence of GenAI tools shift the balance of power between these powerful intermediaries and artistic creators? GenAI equips artists with new tools, enhancing their creativity. Yet, equally important, it also exposes the reality that all creativity is historically situated and contingent upon the existing social, technological, and economic frameworks, including the tools available. Creativity is and never has been, the product of uniquely gifted individuals conjuring something out of nothing but is a situated, networked, contingent process involving historically contingent tools, traditions, identities, and roles. This observation is not meant to decry creativity and individual creators but to acknowledge the historical importance of the “creativity machine,” as revealed—on this account—by GenAI.

What we are now witnessing, therefore, is “old wine in new bottles”, a new form of social exclusion where dominant intermediaries attempt to use the legal system to restrict artists freedom to create. Conversely, GenAI represents a potential moment of liberation for artists and the society as a whole, challenging the power of these intermediaries.