This study empirically examines the relationship between knowledge management practices and firm innovation in the context of service firms in developing countries. The research also examines the mediating role of knowledge application in the relationship between knowledge management practices and firm innovation. From the literature review, this research develops a conceptual model that hypothesises a positive and significant relationship between knowledge generation, knowledge storage, knowledge diffusion, knowledge application and firm innovation. This research elicited responses using a questionnaire from a sample of 293 service firms in Nigeria. A drop-off-pick-up (DOPU) technique was used to obtain the data. The data was analysed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The findings show that knowledge management practices contribute to firm innovation, both directly and indirectly. The results show that knowledge generation, storage and application have significant and positive effect on firm innovation. The findings also show that knowledge application mediates the relationship between knowledge generation, diffusion, storage and firm innovation. The findings imply that knowledge management practices contribute to innovation as a hierarchy, with the link through knowledge application having the greatest impact on firm innovation.

The resource-based view (RBV) of the firm which seeks to explain the underlying performance differential among firms explains that the possession of unique organisational resources by some firms explain why they outperform other firms and thus, experience a sustainable competitive advantage (Alegre, Sengupta, & Lapiedra, 2013; García-Álvarez, 2015). Previous studies have reported that innovation is a dynamic process that drives sustainable competitive advantage and economic growth for individual firms and nations (Chen, Yin, & Mei, 2018; Darroch & McNaughton, 2002). Due to increased competition, driven by globalisation and the advancement of regional and global economies, innovation is an important element if firms wish to remain competitive (Chen et al., 2018). Dickel and Moura (2016) notes that the ability of firms to innovate is one of the key features of competitive, dynamic and progressive organisations. Given the importance of innovation to firms, researchers have been seeking ways to understand how innovation can be improved in firms (Darroch & McNaughton, 2002; Donate & Guadamillas, 2011; Donate & Pablo, 2015; Hamdoun, Chiappetta Jabbour, & Ben Othman, 2018). In recent years, with the emergence of knowledge management, researchers have sought to understand how knowledge management practices and systems facilitate innovation (Johannessen, 2008; Lai & Lin, 2012; López-Nicolás & Meroño-Cerdán, 2011; Lundvall & Nielsen, 2007; Mardani, Nikoosokhan, Moradi, & Doustar, 2018; Plessis, 2007). Some of these studies argue that the management of knowledge is an important antecedent of a firm’s innovation capacity (Donate & Pablo, 2015). Costa and Monteiro (2016) argues that firms can experience sustained competitive advantage when they apply knowledge in new and significantly improved products and services, organisational practices, production processes, marketing strategies and innovation.

Despite the increased interest in knowledge management and innovation, very limited studies have provided an empirical evidence linking knowledge management practices with firm-level innovation, especially from a developing country perspective. Focusing on the link between knowledge management and innovation is important for strategic and theoretical reasons. First, it is important because researchers have increasingly recognised the need to identify, manage and develop intangible assets such as intellectual capital and knowledge in order to facilitate and enhance firm value (Darroch, 2005). Darroch and McNaughton (2002) observes that there is little empirical evidence that offer a direction on how these intangible assets can be managed. Secondly, most of the previous studies that examine the link between knowledge management and innovation take a developed country perspective (Alegre et al., 2013; Apak, Tuncer, Atay, & Koşan, 2012; Darroch & McNaughton, 2002; Dickel & Moura, 2016; Donate & Guadamillas, 2011; Donate & Pablo, 2015; García-Álvarez, 2015). Very limited studies have examined the link between knowledge management and innovation from a developing country perspective. A recent study by Gaviria-Marin, Merigó, and Baier-Fuentes, (2018) using bibliometric analysis demonstrate that very few studies focus on knowledge management-related issues in developing countries, especially Africa. Anning-Dorson (2018) demonstrate that the effect of firm-level practices can be context specific, thus it is essential for researchers to investigate practices that suit different contexts. Studies that take a developed country perspective often present a limited perspective, because they offer few implications and make little theoretical advances for firms in other economic and geographical contexts (Anning-Dorson, 2018). Focusing on only developed country context blur our understanding of the nature of emerging markets and the significant ways in which the market structures of developing countries differ from those of the developed markets. Replicating studies from developed economies without a proper contextual delineation, may substantially reduce the contributions of emerging markets to research and the world economy. This article makes an empirical contribution by testing the relationship between different knowledge management practices and innovation effectiveness, focusing on service firms in an emerging market. This is essential because innovation process depends heavily on knowledge.

This study makes three contributions to the literature. First, the paper conceptualises knowledge management as an organisational function involving many practices that are context-specific which can improve innovation effectiveness. Secondly, the paper demonstrates that different knowledge management practices interact in different ways to enhance innovation effectiveness. Third, the paper provides an analysis of how knowledge management practices interact with firm innovation in developing country service firms.

Literature reviewThis research draws from the knowledge-based view to explore the relationship between different knowledge management practices and innovation performance. The Knowledge-Based View (KBV) of the firm builds and extends the RBV with emphasis on how firms create, acquire, protect, transfer and use knowledge (Grant, 1996; Nonaka & Toyama, 2015; Nonaka, 1994). KBV perceives knowledge as the most significant strategic organisational resource in terms of market value. Nonaka (1994) notes that the core purpose of an organisation is to create and apply knowledge. From the perspective of KBV, competitive advantage is achieved through a firm’s ability to utilise and develop its knowledge assets (Cabrera-Suárez, Saá-Pérez, & García-Almeida, 2001). By nature, most knowledge resources are dynamic and intangible, with unique characteristics that make competitive advantage sustainable because knowledge provides the foundation for sustainable differentiation that is difficult to imitate (Curado & Bontis, 2006). Though complex, Silvia and Juan-Gabriel (2014) notes that the integration and alignment of intangible resources such as knowledge resources is crucial to innovation.

Knowledge management practicesThe importance of knowledge as a source of competitive advantage has been recognised by the knowledge-based view of the firm. Because of the relevance of knowledge, academics and practitioners are becoming increasingly interested in knowledge management (KM) as a discipline (Alegre et al., 2013; Darroch, 2005; Gaviria-Marin et al., 2018; Swan, Newell, Scarbrough, & Hislop, 1999). This is because of the role of knowledge in improving productivity, creating sustainable competitive advantage, creation and protection of a firm’s intangible assets (Alegre et al., 2013; Gaviria-Marin et al., 2018; Lopes, Scavarda, Hofmeister, Thomé, & Vaccaro, 2017). Despite the growing interest in KM, it is still an elusive concept because there is no universally accepted definition of KM (Darroch & McNaughton, 2002). Nonaka (1994), p. 15) describes knowledge as “a multifaceted concept with multi-layered meanings”. Darroch (2005), p. 211) defines KM as the “management function that creates or locates knowledge, manages the flow of knowledge within organisations and ensures that the knowledge is used effectively and efficiently for the long-term benefit of the organisation”. Lai and Lin (2012) used KM to describe how organisational members acquire and create knowledge from inside and outside the organisation. KM describes how knowledge is acquired, created, codified and used within organisations (Shujahat et al., 2017). In this article, KM is used to describe processes that obtain and use knowledge from within and outside the organisation in ways that can lead to the achievement of organisational objectives.

Though these practices may differ from study to study, KM represents a process (Afacan Fındıklı, Yozgat, & Rofcanin, 2015). Alegre et al. (2013) describes KM practices as organisational practices that are based on the application and use of knowledge. Early conceptualisations of KM practices focused on the process of knowledge creation and transfer with a emphasis on tacit and explicit knowledge (Dalmarco, Maehler, Trevisan, & Schiavini, 2017; Nonaka, 1994). Recent conceptualisations describe KM practices in different ways. Whilst some studies identify dissemination and storage as the main KM practices (Alegre et al., 2013), others have identified acquisition, assimilation, transformation and exploitation as more comprehensive dimensions of KM practices (Xie, Zou, & Qi, 2018). For instance, Lai and Lin (2012) identified (a) knowledge creation and acquisition, (b) knowledge diffusion and integration and (c) knowledge storage as the three dynamic processes that capture KM practices. Al-Emran, Mezhuyev, Kamaludin, and Shaalan, (2018) identified knowledge creation, transfer and application as the key KM processes. A comprehensive review by Costa and Monteiro (2016) identifies acquisition, storage, codification, sharing, application and creation as the key KM processes. Other previous studies have described these processes as either exploitative or explorative practices. Knowledge exploration describe activities such as knowledge creation which seeks to create new knowledge. Knowledge creation activities are typically internal firm initiatives that can create new knowledge through R&D activities. This can involve the creation of new content or replacing old content in the organisation’s tacit and explicit knowledge pool (Donate & Pablo, 2015). Some studies have identified knowledge creation as a prerequisite for innovation (Costa & Monteiro, 2016).

Knowledge exploitation on the other hand describe practices such as transfer, storage and application and how they leverage existing knowledge stocks (Donate & Guadamillas, 2011; Menaouer, Khalissa, Abdelbaki, & Abdelhamid, 2015; Stanković & Micić, 2018). Knowledge transfer describe processes that facilitate the distribution of knowledge from one place, person or ownership to another (Hamdoun et al., 2018). It describes how one unit within an organisation is affected by the experience of another. Alegre et al. (2013) describe knowledge storage as a class of procedures and systems for storing and managing knowledge. These are often IT-based systems that support and enhance operational knowledge storage and retrieval. Such knowledge resides in various forms, including codified human knowledge, expert systems, written documentation, documented procedures and processes of tacit knowledge acquired by individuals and networks of individuals (Donate & Pablo, 2015). Lai, Hsu, Lin, Chen, and Lin (2014) in their study found that knowledge storage influences innovation performance. Previous studies suggest that knowledge application is a fundamental success factor for the development of new products and a key facilitator of innovation and performance (Hamdoun et al., 2018; Mardani et al., 2018). The main goal of knowledge application is to integrate knowledge obtained from internal and external sources to drive organisational objectives (Shin, Holden, & Schmidt, 2001). Boateng and Agyemang (2015) describes knowledge application as processes within organisations that enable organisations to use and leverage knowledge in ways that improve its operations, develop new products and generate new knowledge assets. Through knowledge application, organisations can locate the source of competitive advantage by offering knowledge integration methods to solve organisational problems (Shin et al., 2001). This is one of the fundamental aspects of KM because the key goal of KM is to ensure that available knowledge is applied for the benefit of an organisation. Research evidence suggest that when knowledge is effectively applied, it reduces cost and increases the efficiency of organisations (Allameh, Zare, & davoodi, 2011).

Innovation in service firmsIn an increasingly service-centred economy, service innovation is a significant way for firms to maintain their competitive advantage (Chen, Wang, Huang, & Shen, 2016). Most previous studies take a limited view of innovation in services, with a greater focus on technological innovation (Hertog, der, & Jong, 2010). Due to the intangible nature of services and the role of customer interaction, a bias towards technological innovation is often inadequate to explain innovation in service firms. This is because when compared to manufacturing, services are less standardised, more dispersed and less centralised with less focus on products. Some previous studies also argue that service innovation is becoming an important element in manufacturing firms (Cheng & Krumwiede, 2017; Ettlie & Rosenthal, 2012; Santamaría, Jesús Nieto, & Miles, 2012). Hertog et al. (2010), p. 494) defines innovation in services as a “new service experience or service solution that consists of one or several of the following dimensions: new service concept, new customer interaction, new value system/business partners, new revenue model, new organizational or technological service delivery system”. Innovation in services can also emerge from a novel combination of existing services, technologies, people and approaches to satisfy existing and potential customers (Chen et al., 2016). From the foregoing, this study defines innovation in service as the process of developing something new or a combination of existing services in new ways that is beneficial to a target audience. This definition captures the service process as a constellation of activities that involves the customer in the production process (Chen & Tsou, 2012). However, the definition also recognises that innovation in services can have a variety of meanings and applications, apply to a variety of different levels and areas of interactivity (Chen, Batchuluun, & Batnasan, 2015). Hence, the degree of service innovation can range from totally new or discontinuous innovation to a service that may be as a result of a minor improvement or adaptation of an incremental nature (Cheng & Krumwiede, 2012).

Bettencourt, Brown, and Sirianni, (2013) argues that service firms should approach innovation in way that enables them to identify opportunities for breakthrough service offerings that are not constrained by current or proposed service offerings. This demonstrates that one of the key elements of service innovation is performance improvement and the strengthening of the capacity of firms to compete (Chen et al., 2015). Chen et al. (2016) notes that service innovation enable firms to enhance learning capabilities and gain access to market trends which can enhance firm performance. Previous evidence suggests that there is a formidable relationship between service innovation and new service performance (Cheng & Krumwiede, 2012).

Research hypothesesKM practices and innovationThere is a dearth of research linking KM practices and innovation, especially from a developing country perspective. Darroch and McNaughton (2002) argues that the few studies that address the link fail to account for different types of innovation (e.g. radical and incremental and between industries (manufacturing and services). It is not also clear how different KM practices contribute to innovation. KM practices is a set of strategies, initiatives and activities that firms use to generate, transfer, apply and store knowledge (Donate & Pablo, 2015). Plessis (2007) describes knowledge and KM roles in innovation as enabling the codification and sharing of tacit knowledge. Previous studies have argued that managing knowledge effectively enhances a firm’s innovation capacity (Donate & Guadamillas, 2011; Donate & Pablo, 2015). This is consistent with the findings of Darroch and McNaughton (2002) that KM practices have an influence on innovation performance. Donate and Pablo (2015) also demonstrate that KM practices (exploration and exploitation) have the capacity to improve form performance in product innovation. Beside the direct relationship between KM practices and innovation, KM practices also mediate the relationship between many other variables and innovation (Costa & Monteiro, 2016). Recognising the important role of KM to innovation, Abou-Zeid and Cheng (2004) argues that the compatibility between knowledge manipulation activities and the type of knowledge associated with innovation can influence the success of the innovation process.

Previous findings on the connection between KM and innovation effectiveness are mixed. For instance, Inkinen, Kianto, and Vanhala, (2015) found that whilst KM can support innovation performance, not all the practices are directly associated with innovation performance. Whilst some findings show that knowledge protection practices have no direct influence on innovation (Inkinen et al., 2015), others demonstrate that each dimension of knowledge improves firms' innovation performance (Wang, Chen, & Fang, 2018). Xie, Wang, and Zeng, (2018) found that knowledge acquisition has a significant positive impact on firms' radical innovation, however, Darroch and McNaughton (2002) found that KM practices (acquisition, dissemination and responsiveness to knowledge) significantly predicts incremental innovation. On the contrary, Shujahat et al. (2017) found that knowledge creation has indirect effect on innovation. Wang and Wang (2012) found that knowledge sharing practices (explicit and tacit) facilitate innovation and performance. The findings of Wang and Wang (2012) further demonstrates that whilst explicit knowledge sharing has more significant effects on innovation speed and financial performance, tacit knowledge sharing has more significant effects on innovation quality and operational performance. Ritala, Olander, Michailova, and Husted, (2015) finds support that knowledge sharing has a positive effect on innovation performance. Despite the findings suggesting that KM practices contribute to innovation performance in various ways, Plessis (2007) argues that the growth in the amount of knowledge accessible to an organisation increases the complexity of innovation, because innovation is extremely dependent on knowledge. Mardani et al. (2018) demonstrates that KM activities directly impact innovation and organizational performance, and indirectly through an increase in innovation capability. Particularly, the findings reveal that knowledge creation, integration, and application facilitate innovation and performance (Mardani et al., 2018). Whilst these findings demonstrate that the relationship between KM practices and innovation may be mixed, they do not show how different knowledge management practices interact to influence innovation. This study examines different KM practices and how they can be integrated to enhance innovation capability of firms. As Darroch (2005) suggests, firms with the capacity to manage knowledge will utilise resources more efficiently, thus will be more innovative and perform better. This study identifies knowledge diffusion, generation, storage and application as the core KM practices that can enhance firm innovation. Thus, this research postulates that KM practices will have a direct influence on service firm innovation.H1 KM practices have a direct and positive influence on firm innovation. Knowledge generation will have a positive influence on firm innovation. Knowledge diffusion will have a positive influence on firm innovation. Knowledge storage will have a positive positive influence on firm innovation.

The focal point of knowledge management is knowledge application (KA) because it makes knowledge more active and relevant for the creation of firm value (Bhatt, 2001; Choi, Lee, & Yoo, 2010). Because of the tacit nature and stickiness of knowledge, the KBV argues that the value of knowledge derives from its application (Jugend, da Silva, Oprime, & Pimenta, 2015). When organisations correctly apply relevant knowledge, they reduce the likelihood of making mistakes, reduce redundancy, increase efficiency and continuously translate their organisational expertise into embodied products (Chen & Huang, 2009). Through knowledge application, organisations can speed up their new product development process and the processing of administrative and technology systems. KA responds to the different types of knowledge that is available within an organisation, and it applies knowledge that has been created and shared (Chen & Huang, 2009; Shujahat et al., 2017). Shujahat et al. (2017) points out that KA is more important than other processes such as created knowledge or shared knowledge because knowledge is of no importance until it is applied. Sarin and McDermott (2003) observes that KA enable organisational members to maximise desired outcomes. Whilst past research either neglects KA or examine KA as having a direct association with innovation performance (Choi et al., 2010), this study argues that KA can mediate the relationship between other KM practices (generation, diffusion and storage) and firm innovation. This means that knowledge generation and diffusion cannot be effective if they are not applied to deliver goods and services and solve problems effectively (Jugend et al., 2015). This study therefore postulates that:H2 Knowledge application mediates the relationship between KM practices and a firms’ innovation

This research employs a survey methodology to collect primary data for empirical analysis. The sample is made up of a selection of service firms drawn from a research population of 1124 service firms. The list was obtained from listed and regulated service firms by Central Bank of Nigeria and National Bureau of Statistics. The firms consist of a mix of innovative financial service firms operating in the business-to-business (B2B) and the business-to consumer (B2C) sectors. The service sector is suitable because it is a very significant sector with evidence of implementation of knowledge management systems. The services sector in Nigeria accounted for 55.00 percent of GDP in the first half of 2016, up from 54.46 per cent in the corresponding period in 2015, reflecting further changes in structure of the Nigerian economy (NBS NCC report, 2016). The service sector is a very knowledge intensive and innovative, hence an appropriate sector to examine the association between KM practices and innovation. A simple random technique was used to identify the sample firms. The sampling technique followed the steps recommended for studies utilising Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) (Blunch, 2013). A rule of thumb for studies employing SEM is a recommended sample of 200 as fair and 300 as good (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Iacobucci, 2010). The data was obtained through research assistants who were trained and adequately briefed before they disseminated the research questionnaire. A sample of 293 service firms in Nigeria using a drop-off-pick-up (DOPU) technique was used in this study.

Measurement of variablesSeveral steps were followed in developing the questionnaire. Special attention was given to different levels, language, question order, response format, scale types, design, and general context of the research. This research creates the scale to measure KM practices, adapting measurement items from existing literature. All the items were measured using a 7-point Likert type scale. KM practices is measured with forty-one items on the four KM processes (knowledge diffusion, generation, storage and application). This research opted for a 12-item scale adapted from Gold, Malhotra, and Segars, (2001) on firm knowledge acquisition process scale to measure knowledge generation and 12-item called to measure knowledge application. To measure knowledge diffusion two items were adopted from Darroch (2005), four items for measuring knowledge dissemination practices from Villar, Alegre, and Pla-Barber, (2014) and Alegre, Sengupta, and Lapiedra, (2011). To measure knowledge storage, this research adopted 10 items from Alegre et al. (2011) and Villar et al. (2014) (3 items); Gold et al. (2001)) (4 items) and (Lee, 2014) (2 items).

Innovation is a complex and multidimensional concept (Martínez-Román, Gamero, & Tamayo, 2011). Hence, it is a major challenge when seeking to conceptualize innovation in a feasible way for empirical investigation at the aggregate level (Ngo & O’Cass, 2009). In this study, the researcher adopts an interactive view of innovative processes in the firm, hence innovation is conceptualised as the internal ability that conditions the entire organization to innovate and the capacity to respond properly to changes in the firm’s environment (Calantone, Cavusgil, & Zhao, 2002; Tang, Wang, & Tang, 2013; Wang, Dou, Zhu, & Zhou, 2015). To capture the multidimensional nature of innovation, this research assesses innovation with 10 items developed based on Ngo and O’Cass (2009) innovation-based capability scale and Calantone et al. (2002) firm innovativeness scale. All the items are measured using multi-item scale with seven-point Likert-type scales.

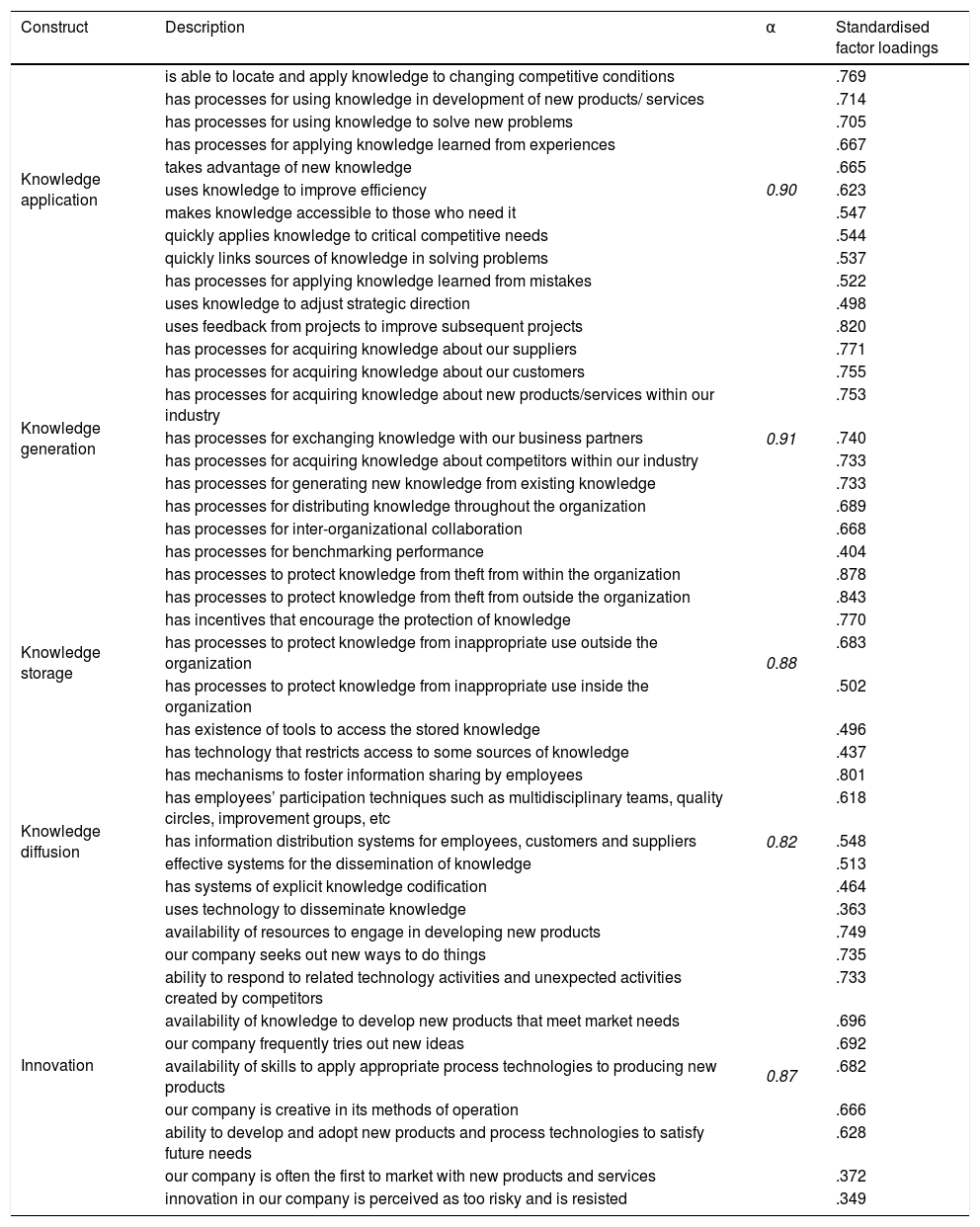

ResultsMeasurement modelAn exploratory factor analysis was carried out to uncover the structure of the variables. Items with low factor loadings (<.4) and items that strongly load on more than one factor (>.4) were removed resulting in 5 factors. 4 items from knowledge storage, 3 items from knowledge creation, 1 item from knowledge transfer, 1 item from knowledge application and 4 items from innovation. These items were removed because of a strong cross-loading or because they loaded below 0.4. Cronbach alpha (α) was used to assess the internal reliability of the scales. As shown in Table 1, the α ranges between 0.82 to 0.90 which is higher than the recommended threshold of α=0.70 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Results of exploratory factor analysis (Page 15).

| Construct | Description | α | Standardised factor loadings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge application | is able to locate and apply knowledge to changing competitive conditions | 0.90 | .769 |

| has processes for using knowledge in development of new products/ services | .714 | ||

| has processes for using knowledge to solve new problems | .705 | ||

| has processes for applying knowledge learned from experiences | .667 | ||

| takes advantage of new knowledge | .665 | ||

| uses knowledge to improve efficiency | .623 | ||

| makes knowledge accessible to those who need it | .547 | ||

| quickly applies knowledge to critical competitive needs | .544 | ||

| quickly links sources of knowledge in solving problems | .537 | ||

| has processes for applying knowledge learned from mistakes | .522 | ||

| uses knowledge to adjust strategic direction | .498 | ||

| Knowledge generation | uses feedback from projects to improve subsequent projects | 0.91 | .820 |

| has processes for acquiring knowledge about our suppliers | .771 | ||

| has processes for acquiring knowledge about our customers | .755 | ||

| has processes for acquiring knowledge about new products/services within our industry | .753 | ||

| has processes for exchanging knowledge with our business partners | .740 | ||

| has processes for acquiring knowledge about competitors within our industry | .733 | ||

| has processes for generating new knowledge from existing knowledge | .733 | ||

| has processes for distributing knowledge throughout the organization | .689 | ||

| has processes for inter-organizational collaboration | .668 | ||

| has processes for benchmarking performance | .404 | ||

| Knowledge storage | has processes to protect knowledge from theft from within the organization | 0.88 | .878 |

| has processes to protect knowledge from theft from outside the organization | .843 | ||

| has incentives that encourage the protection of knowledge | .770 | ||

| has processes to protect knowledge from inappropriate use outside the organization | .683 | ||

| has processes to protect knowledge from inappropriate use inside the organization | .502 | ||

| has existence of tools to access the stored knowledge | .496 | ||

| has technology that restricts access to some sources of knowledge | .437 | ||

| Knowledge diffusion | has mechanisms to foster information sharing by employees | 0.82 | .801 |

| has employees’ participation techniques such as multidisciplinary teams, quality circles, improvement groups, etc | .618 | ||

| has information distribution systems for employees, customers and suppliers | .548 | ||

| effective systems for the dissemination of knowledge | .513 | ||

| has systems of explicit knowledge codification | .464 | ||

| uses technology to disseminate knowledge | .363 | ||

| Innovation | availability of resources to engage in developing new products | .749 | |

| our company seeks out new ways to do things | 0.87 | .735 | |

| ability to respond to related technology activities and unexpected activities created by competitors | .733 | ||

| availability of knowledge to develop new products that meet market needs | .696 | ||

| our company frequently tries out new ideas | .692 | ||

| availability of skills to apply appropriate process technologies to producing new products | .682 | ||

| our company is creative in its methods of operation | .666 | ||

| ability to develop and adopt new products and process technologies to satisfy future needs | .628 | ||

| our company is often the first to market with new products and services | .372 | ||

| innovation in our company is perceived as too risky and is resisted | .349 |

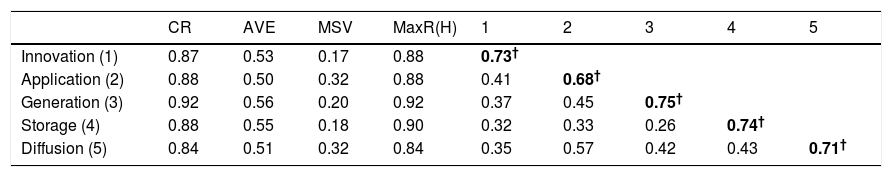

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to evaluate the overall measurement model and to assess the reliability and validity of the constructs. To effectively assess the validity of the measurement model, discriminant and convergent validity were assessed. Discriminant validity measures the degree to which factors that are supposed to measure a specific construct are actually unrelated (Wang & Wang, 2012). Fornell and Larcker’s approach was used to assess discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Using this approach, the AVE for each of the research constructs should be higher than the squared correlation between the construct and any of the other constructs. As shown in Table 2, the measurement model demonstrates a satisfactory discriminant validity. The diagonal elements (in bold†) shown in Table 2 are the squared multiple correlations between the research variables. As shown in the table, the AVE ranges from 0.51 to 0.56 while the diagonal values range from 0.684 to 0.749, indicating that the diagonal variables are higher than the various AVE values suggesting that all the constructs in this study have adequate discriminant validity.

Reliability, validity statistics and correlations (Page 15).

| CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation (1) | 0.87 | 0.53 | 0.17 | 0.88 | 0.73† | ||||

| Application (2) | 0.88 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 0.88 | 0.41 | 0.68† | |||

| Generation (3) | 0.92 | 0.56 | 0.20 | 0.92 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.75† | ||

| Storage (4) | 0.88 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.74† | |

| Diffusion (5) | 0.84 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.84 | 0.35 | 0.57 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.71† |

Notes: CR=composite reliability; AVE=average variance extracted; MSV=maximum shared variance; MaxR(H)=maximum reliability; (H) and †=square root of AVE.

Convergent validity measures the extent to which factors that ought to measure a single construct agree with each other. In this research, convergent validity was assessed using composite reliability and average variance explained (AVE). Using these measures, composite reliability (CR) should be above 0.6 and AVE should be above 0.5 for all constructs. As shown in Table 2, CR ranges from 0.84 to 0.92 while the AVEs range from 0.51 to 0.56. These results show that the model meets the criteria for assessing convergent validity.

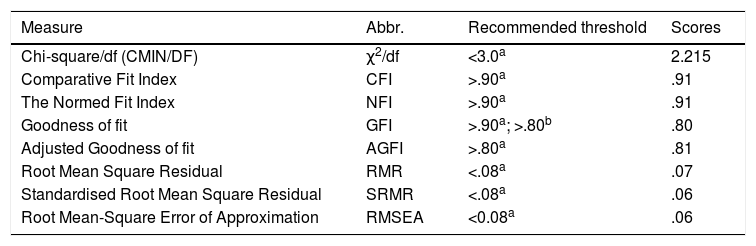

The measurement model fit was assessed by evaluating the root mean square of approximation (RMSEA), absolute fit measures including observed normed χ2 (χ2/df), Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Goodness of fit (GFI) and Adjusted Goodness of fit (AGFI). As shown in Table 3, all the fit indices met the recommended thresholds for evaluating model fit. It can therefore be concluded that the model fits the data well and can thus be used to explain the research hypotheses.

Fit indices of CFA model.

| Measure | Abbr. | Recommended threshold | Scores |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square/df (CMIN/DF) | χ2/df | <3.0a | 2.215 |

| Comparative Fit Index | CFI | >.90a | .91 |

| The Normed Fit Index | NFI | >.90a | .91 |

| Goodness of fit | GFI | >.90a; >.80b | .80 |

| Adjusted Goodness of fit | AGFI | >.80a | .81 |

| Root Mean Square Residual | RMR | <.08a | .07 |

| Standardised Root Mean Square Residual | SRMR | <.08a | .06 |

| Root Mean-Square Error of Approximation | RMSEA | <0.08a | .06 |

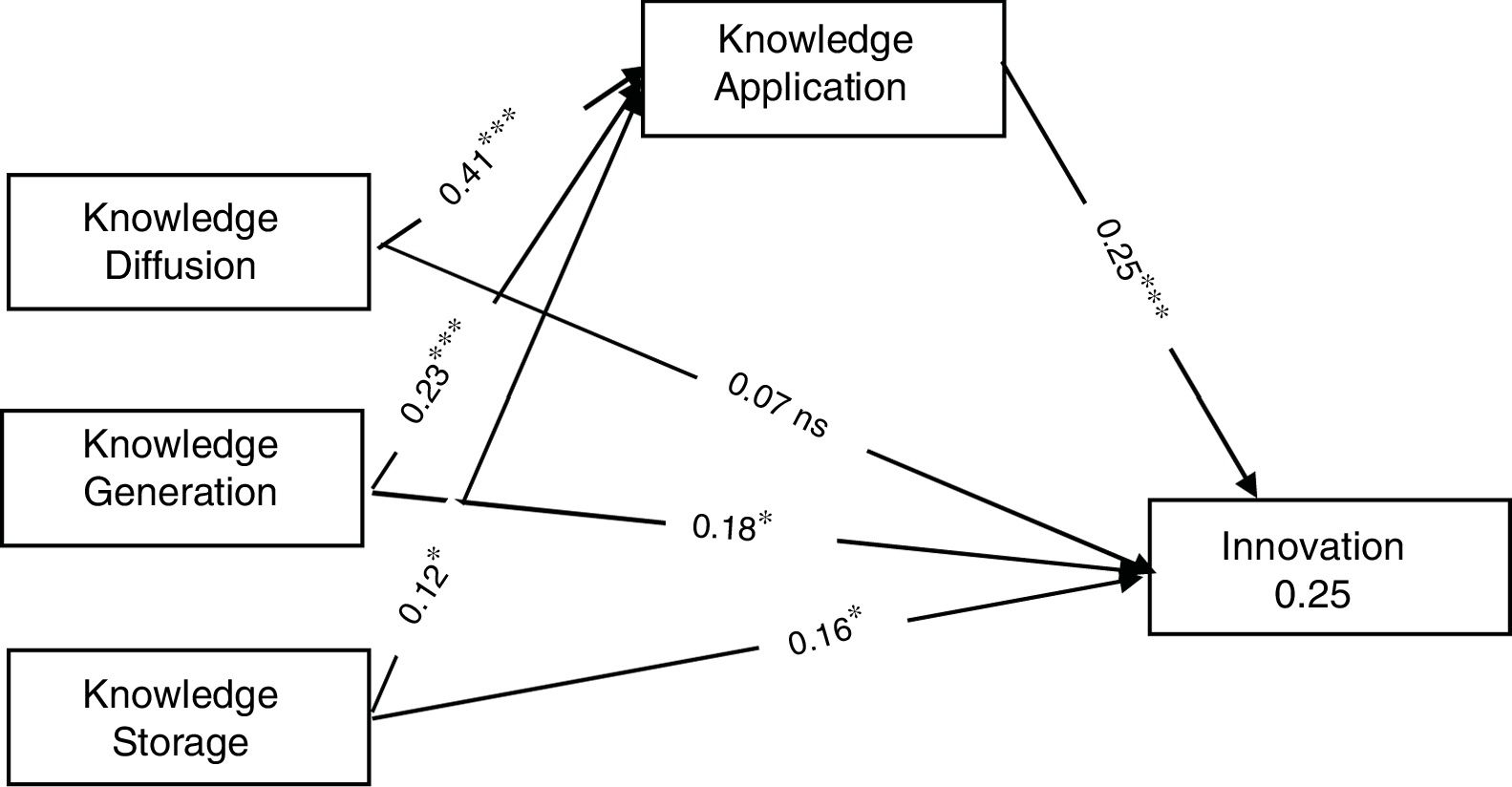

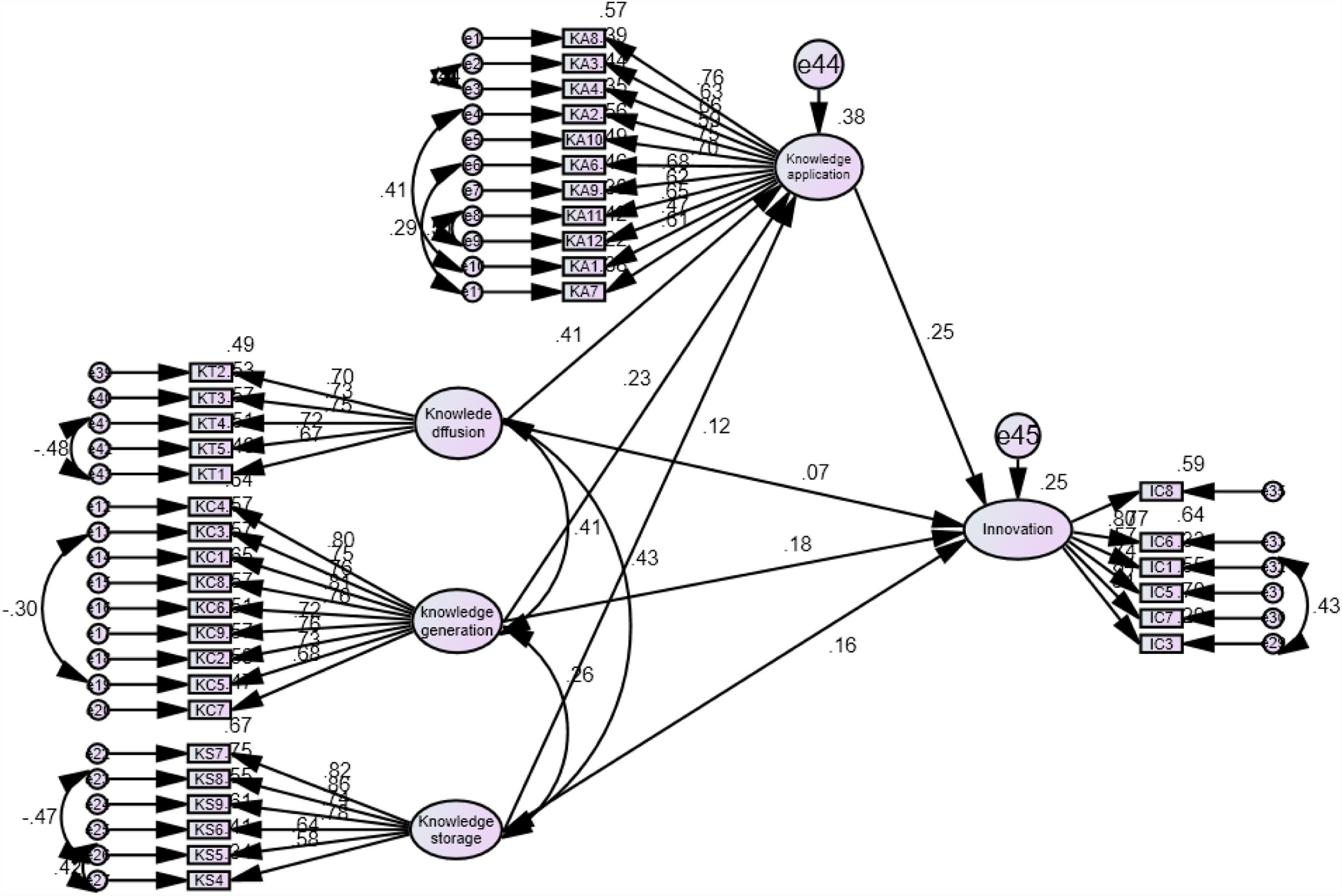

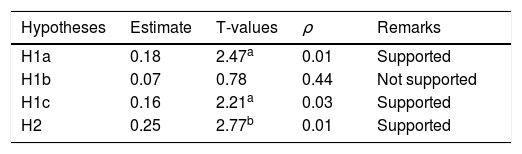

Table 4 and Figure 1 shows the results of the test of hypotheses of the structural relationship between the research variables. For hypothesis 1a, the researcher examined the relationship between knowledge generation practices and firm innovation. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 4, the effect of knowledge generation practices on firm performance (β=0.18; p<0.05) is significant. Hence, hypothesis 1a is supported. Contrary to the findings of hypothesis 1a, hypotheses 1b which examined the link between knowledge diffusion practices and firm innovation is not supported (β=0.07; p>0.05). However, hypothesis 1c which examined the relationship between knowledge storage practices and firm innovation (β=0.16; p<0.05) is supported as shown in Table 4 and Figure 1 respectively.

For hypothesis 2, this study examined the mediating effect of knowledge application practices on the relationship between knowledge management practices and firm innovation. The results of the hypothesis show that knowledge application positively mediates the relationship between knowledge generation, knowledge diffusion, knowledge storage and firm innovation (β=0.25; p<0.05). The findings also reveal that knowledge generation (β=0.23; p<0.05) and knowledge storage (β=0.12; p<0.05) are significantly related to knowledge application. However, as shown in Table 4 and Figure 1, knowledge diffusion showed the strongest relationship (β=0.41; p<0.05), suggesting that knowledge management practices do not have the same effect on firm level innovation (Figure 2).

Discussion, implications and concluding remarksTheoretical contributionsMany authors have suggested that the management of knowledge is an important antecedent of a firm’s innovation capacity. In recent years, many authors have discussed the influence of different knowledge management practices on various organisational outcomes. Despite the increased research interest in knowledge management and innovation, very limited studies have provided an empirical evidence linking knowledge management practices with innovation effectiveness, especially from a developing country perspective. By proposing a model demonstrating the influence of knowledge generation, knowledge storage, knowledge diffusion, knowledge application and firm innovation, this study fills the gaps in existing literature. The empirical findings of this study confirm three out of the four hypotheses proposed for this study. Through the mediation analysis, this study confirms the mediator role of knowledge application in service firms. This study does not just justify the influence of knowledge management practices (generation, diffusion and storage) on firm innovation, it also explores how knowledge application aids other knowledge management practices to enhance firm innovation.

The findings also show that knowledge management practices contribute to firm innovation, both directly and indirectly. There are two implications of these findings. First, knowledge management practices contribute to innovation as a hierarchy, with knowledge application mediating the link between knowledge generation, knowledge diffusion, knowledge storage and firm innovation. Secondly, the findings show that not all knowledge management practices contribute to firm innovation. For instance, in this research, only knowledge generation, storage and application contribute to firm innovation. Knowledge diffusion contributes indirectly to firm innovation through knowledge application. The findings obtained in this study confirms that the focal point of knowledge management is knowledge application (Bhatt, 2001). As shown by Choi et al., 2010, knowledge application makes knowledge more active and relevant to the creation of firm value. Chen and Huang (2009) and Shujahat et al. (2017) supports the role of knowledge application by demonstrating that knowledge application responds to the different types of knowledge that is available within an organisation, and aids the use of knowledge that has been created and shared

The findings obtained in this study is consistent with the findings of Lai et al. (2014) which found that knowledge storage influences firm innovation performance. The findings also support the findings of previous studies suggesting that knowledge application is a fundamental success factor for the development of new products and a key facilitator of innovation and performance (Hamdoun et al., 2018; Mardani et al., 2018). The findings are consistent with previous studies which argue that when knowledge is managed effectively, it increases a firm’s innovative capacity and competitiveness (Donate & Guadamillas, 2011; Donate & Pablo, 2015). While some previous studies (e.g., Wang & Wang, 2012) accentuates the role of knowledge sharing in firm innovation, this study has shown that knowledge sharing is more relevant to innovation when mediated by knowledge application. This shows that knowledge application mediates the relationship between other knowledge management practices and firm innovation. The study also contradicts the findings of Yeşil, Koska, and Büyükbeşe, (2013) that knowledge sharing positively influences firm innovation. The findings obtained in this study shows that knowledge sharing does not have a significant influence in firm innovation. As shown in the study of Inkinen et al. (2015), whilst KM practices can support innovation performance, not all the practices are directly associated with innovation.

Practical implicationsThere are some practical implications that can be derived from this study. The relationship between different knowledge management practices provide a guide on how service firms in developing countries can enhance innovation. The different practices suggest specific practices that service organisations can focus on. Service firms can reflect on the roles of different knowledge management practices and how they interact in different ways to influence firm innovation. The study has shown that service firms that apply the explicit and tacit knowledge can improve their innovation effectiveness. Future research can focus on specific knowledge management practices and how they influence firm innovation. For instance, this study has found that knowledge application leverages other practices to facilitate innovation. Future research can therefore focus on specific practices of knowledge application and how the mechanisms work in practice.

Limitations and opportunitiesFirst, the research findings are drawn from self-reported data. This could lead to potential common method variance. Secondly, the approach used in this study is cross-sectional and does not reflect how the mechanisms examined in this research perform in the long-term. Third, knowledge management practices are multidimensional. This study has focused on only four knowledge management practices; knowledge generation, knowledge storage, knowledge diffusion and knowledge application. There are other dimensions of knowledge management that have not been examined and can equally be useful in explaining firm innovation in service firms. As a suggestion for future research, other researchers can examine the effect of other knowledge management practices on firm innovation across different industries. Such studies can also adopt a longitudinal approach to examine the long-term effect of these knowledge management practices. Despite these limitations, this study has provided practical empirical evidence to demonstrate the associations between knowledge management and firm innovation in service firms.