Knowledge Hiding is a pervasive problem in the workplace, which can have various negative consequences for individuals and organizations. Drawing from the underpinning of complexity theory, this study investigates the complex causal interrelationships associated with knowledge hiding in the workplace. That is, we explore the interrelationships of individual-level factors: i) demographic characteristics (age, gender, education and experience), and ii) personality traits (i.e., Big-5 and the Dark Triad), and knowledge hiding behaviours. We collected data from 157 employees in the hospitality sector and analyzed by using fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). Our results highlighted multiple configurations of the demographic characteristics and personality traits (i.e., causal conditions) leading to knowledge hiding behaviours (i.e., outcome). Our findings revealed a total of 25 unique profiles combining personality traits and demographics factors–14 associated with the presence of knowledge hiding, and 11 linked to its absence. In particular, Machiavellianism emerged as a core condition driving the presence of knowledge hiding, while extraversion was identified as a core condition associated with its absence. This is the first-ever study comprehensively investigating distinct profiles resulting from the interplay between employees' personality traits and demographic factors associated with their knowledge hiding behaviour.

In today's complex and dynamic work environment, the success of nearly every organization depends on its ability to manage knowledge resources effectively (AlMulhim, 2023; Sepúlveda-Rivillas et al., 2022). Recently, there has been growing interest in understanding when and why employees share (or hide) knowledge, as well as the potential benefits (or downsides) for both employees and organizations (Arain et al., 2022, 2023). Despite significant efforts, knowledge hiding (hereafter; KH) remains a pervasive phenomenon at workplace, and a barrier to effective knowledge management in organizations (Chen et al., 2022). KH refers to the intentional concealment, withholding, or distortion of information, knowledge, or experiences relevant to a particular task, project, or organization (Connelly et al., 2012). Existing research on knowledge management has predominantly focused on knowledge sharing, often overlooking its counterpart, KH (Peng, 2013). However, our limited understanding of how, when, and why employees engage in KH in the workplace highlights the need for further investigation.

Previous research has shown that this deviant behavior can have several detrimental consequences including decreased productivity (Khoreva & Wechsler, 2020), employee distrust (Arain et al., 2020), and hindered innovation and firm performance (Haar et al., 2022; Xiao & Cooke, 2019). Another body of research has identified the antecedents of KH at various levels, including the individual (e.g., Butt, 2021; Xiao, 2024), interpersonal or group level (e.g., Bari et al., 2023; Jafari-Sadeghi et al., 2022), and organizational levels (e.g., Anand et al., 2023; Kaur & Kang, 2023).

Recent studies have highlighted the significance of examining how individual characteristics contribute to KH in the workplace (e.g., He et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). In this line of research, scholars have particularly underscored the critical role of employees’ personality traits in counterproductive knowledge behaviors (e.g., Serenko, 2024; Wu & Liu, 2023). For instance, Serenko (2024) suggested that employees with psychological disorders (e.g., narcissism and sadism) are more likely to engage in KH behaviors. Notably, among various personality assessment models and frameworks, the Big Five (Big-5) model and the Dark Triad (D-3) have received wide recognition from the scholarly community for examining the relationship between personality traits and workplace attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Balakrishnan et al., 2019; Pan et al., 2018; Soral et al., 2022).

Although some empirical evidence explores the relationships between personality characteristics and KH (e.g., Hamza et al., 2023), our understanding of the individual-level causes of KH remains limited in several ways. Existing research on personality traits and KH reveals conflicting results, further complicating the overall understanding. For instance, Hamza et al. (2023) identified a positive association between KH and three personality dimensions (openness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism) and a negative relationship between extraversion and agreeableness. Conversely, Wu (2021) reported a positive link between all BIG-5 personality dimensions and KH, except for openness to experience. Similarly, while most prior studies have established a connection between d-3 personality traits and KH (e.g., Karim, 2020, 2022), there also exists empirical evidence highlighting the distinct tendencies of d-3 traits—narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism—to influence different KH strategies (Pan et al., 2018). For example, a recent study reported that psychopaths pretend to be unaware (i.e., play dumb), narcissists engage in rationalized hiding, and individuals high Machs employ evasive hiding strategies (Joshi et al., 2024).

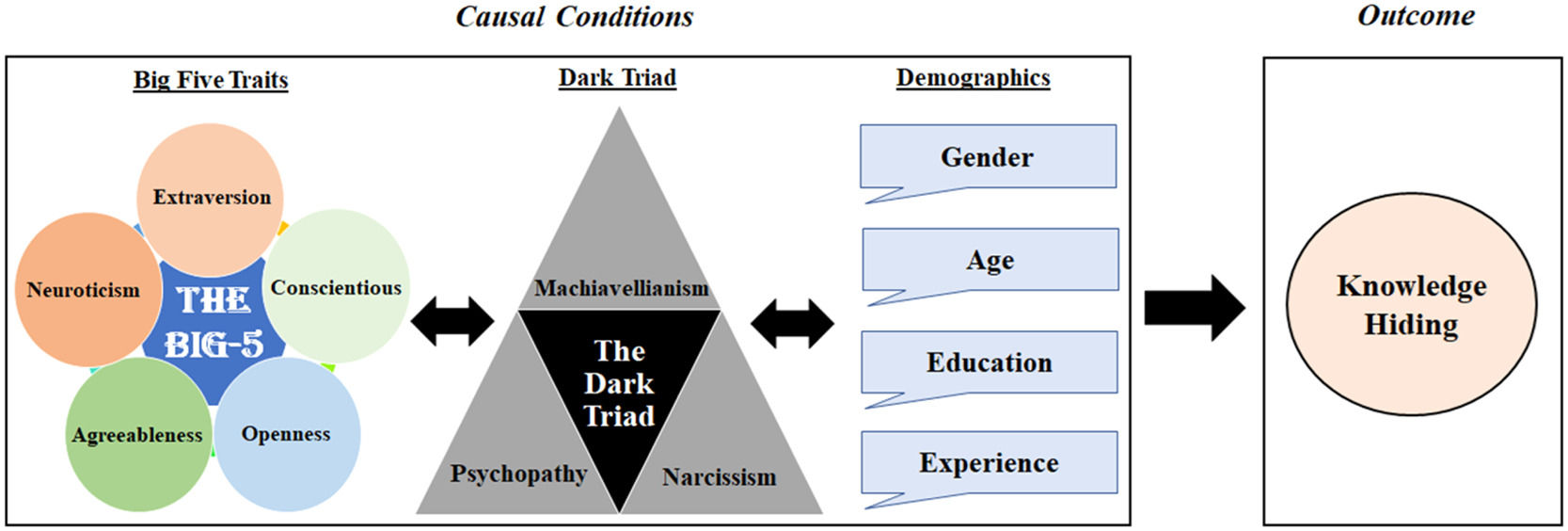

Despite the significant role of individual differences in workplace behaviors, few studies have examined the association between demographic factors and KH (e.g. Zhang et al., 2022). Furthermore, most research has focused on cause-and-effect mechanisms by considering a limited set of individual-level factors (Garg & Anand, 2020; Chawla & Gupt al., 2019), typically within linear relationships. This narrow focus overlooks how various individual-level factors may interact or jointly influence KH in the workplace. However, a synthesized understanding of these linkages is lacking. According to Lemon and Macklin (2021)), "When scholars are no longer limited to binary, dichotomous approaches and understanding, the potential for theory development is enhanced" (p. 222). In this context, complexity theory offers a framework for developing a nuanced, comprehensive understanding of how and when various conditions may lead to specific outcomes (Anderson, 1999). From this perspective, we argue that complex and dynamic interactions among various individual-level factors can influence KH. Therefore, this study aims to present a holistic view of the different combinations of individual factors, such as demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, education, and experience) and personality traits (e.g., Big-5 and d-3) associated with KH behaviors in organizations.

This study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, it expands the understanding of individual-level factors influencing KH by examining a broad range of variables, including age, gender, education, experience, and personality traits. While previous research has addressed some of these factors in isolation, this study adopts a more integrated approach to identify conditions associated with KH. It uniquely examines the combinations of individual-level conditions that influence KH both independently and in various configurations. Second, the findings provide actionable insights for organizations aiming to reduce KH and foster a culture of knowledge sharing. By identifying specific combinations of conditions associated with KH, organizations can develop targeted interventions to mitigate this behavior. Third, this study advances the literature on organizational behavior by demonstrating the utility of complexity theory and fuzzy set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) in understanding complex and dynamic organizational phenomena. By adopting a holistic approach, this study lays a foundation for entrepreneurs and offers valuable insights for future research on KH.

Theory and backgroundKnowledge hiding (KH)KH refers to the deliberate withholding or concealment of information requested by another employee that could benefit others within an organization (Connelly et al., 2012). It is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompassing various forms of hiding, withholding, and distorting information (Shirahada & Zhang, 2022). Connelly et al. (2012) identified three primary dimensions of KH: Evasive Hiding, Playing Dumb, and Rationalized Hiding. Evasive hiding involves intentionally avoiding or redirecting questions, requests for information, or opportunities for sharing knowledge. Playing dumb involves deliberately pretending not to know or understand something, thereby withholding one's knowledge or expertise. Rationalized hiding entails providing justifications or excuses for avoiding knowledge sharing, such as claiming a lack of time, fearing negative consequences, or deeming the knowledge irrelevant.

KH is a distinct phenomenon that can sometimes be conflated with related concepts. For example, some studies have considered KH and knowledge hoarding to be the same (e.g., Evans et al., 2015), while others have treated them as distinct constructs (Connelly et al., 2012) or grouped both under the broader category of knowledge withholding (e.g. Webster et al., 2008). Furthermore, behaviors such as a lack of knowledge sharing, counterproductive work behavior (CWB), workplace aggression, workplace undermining, deception, and incivility in the workplace have been identified as separate from KH (Connelly et al., 2012). However, unlike other counterproductive behaviours, KH stands out as one that is connected to, but distinct from, these behaviours (Serenko & Bontis, 2016).

Demographic characteristics and KHDemographic characteristics have been shown to influence employee behaviors and performance across various work-related settings. Recent studies have focused their investigations on how demographic characteristics (e.g. gender, age, and educational background) can stimulate KH among employees. This includes examining the tendencies and differences of hiding (or sharing) knowledge among older (vs. younger), female (vs. male), and those with higher versus lower levels of education (e.g. Zhang et al., 2023; Andreeva & Zappa, 2023). Existing research indicates that certain demographic characteristics can affect employees’ likelihood of engaging in KH (Arain et al., 2022; Miminoshvili & Cerne, 2022). However, empirical evidence also exists, reporting an insignificant relationship between the demographic characteristics (i.e. age, gender, and education) and KH.

For instance, factors such as employee age, education, and tenure have been explored as potential contributors to KH. Some studies report that individuals with longer tenures, higher educational attainment, and older age are more likely to engage in KH. However, others have found contradictory or insignificant results (e.g., Connelly et al., 2012; Lazazzara & Za, 2019; Oshagbemi, 2000; Zhang et al., 2023). Similarly, debates exist over whether short-term employees are more likely to engage in KH compared to long-term employees. A recent study suggested a less likely association between tenure (as a control variable) and KH (Zhang et al., 2022).

Furthermore, regarding educational background, the literature presents mixed findings. For example, highly educated or overqualified individuals have been linked to KH behaviors in some studies (e.g., Dodokh, 2020; Tian et al., 2022), while others points to an indirect or insignificant relationship between educational level and overall KH. Similarly, mixed results have been reported regarding the relationship between gender and KH. According to Andreeva and Zappa (2023), male and female employees have varying tendencies to hide knowledge by selecting strategies that align with others' perceptions of their social roles (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Rudman & Phelan, 2008). Some studies suggest that women are more likely to engage in KH compared to men, while others report the opposite (e.g., Andreeva & Zappa, 2023; Irum et al., 2020; Koay & Lim, 2023).

Our review of the literature indicates that demographic factors such as age, gender, education, and experience may play a significant role in influencing KH in the workplace. Therefore, this study aims to explore the specific mechanisms through which these demographic characteristics affect KH.

RQ1: To what extent do differences in demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, education, and experience) explain variations in KH?

Personality traits and KHScholars have argued that individual behavioral traits significantly impact attitudes, actions, and performance (e.g., Kim & Patel, 2011; Kim & Nguyen, 2023; Salmony et al., 2022). Recent years have witnessed growing academic interest in understanding the relationship between personality traits and KH among employees (Serenko, 2024).

Personality traits refer to stable patterns of behaviors, thoughts, and feelings that influence an individual's actions and interactions with others (Diener & Lucas, 2019). Among the most commonly studied frameworks is the Big-5 personality model, which comprises five dimensions: conscientiousness, neuroticism, agreeableness, extraversion, and openness to experience (Dennison et al., 2001; Tanasescu et al., 2013). Another widely used model, the Dark Triad (hereafter, D-3), examines three negative personality traits—narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism—and their influence on employee behavior in organizations (Junca & Silva, 2023; Szabó et al., 2023).

Numerous studies have demonstrated a correlation between KH and personality traits. Extraverts, characterized as outgoing, friendly, and socially proactive individuals (Furnham & Fudge, 2008), tend to feel more comfortable sharing information and interacting with others (Rustina et al., 2024). Similarly, openness, a trait closely linked to creativity (Christensen, 2023), is associated with curiosity, imagination, and open-mindedness (Nusbaum & Silvia, 2011). Consequently, individuals with high levels of openness are more likely to acquire and share knowledge with others (Matzler et al., 2008; Cui et al., 2023). Moreover, conscientious individuals, known for their responsibility, trustworthiness, and organizational skills (Hasanah et al., 2022), often value ethical behavior and honesty, which may discourage them from engaging in KH (Chawla & Gupta, 2019). However, their high achievement orientation may sometimes lead them to hide knowledge to maintain a competitive edge (Jain, 2014). Conversely, neurotic individuals, who are more prone to experiencing negative emotions such as depression (Pang & Wu, 2021), may be more likely to engage in KH as a coping mechanism.

Interestingly, the relationship between Big-5 personality traits and KH has yielded inconsistent findings in the literature (Hamza et al., 2023). For instance, some studies indicate that employees scoring high in extraversion and openness are less likely to engage in KH, while those with high scores in conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism are more inclined to do so (Iqbal et al., 2020). However, other research has identified positive associations between openness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and KH (Hamza et al., 2023).

Furthermore, individuals exhibiting D-3 traits—psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism—are more prone to unethical and manipulative behaviors (Forsyth et al., 2012; Harrison et al., 2018). Studies have found that employees with D-3 traits often engage in KH to gain power or control over others (Pan et al., 2018; Karim, 2022). Notably, the effects of narcissism and psychopathy on KH can be stronger in men than in women (Pan et al., 2018). Joshi et al. (2024) further elaborated that different D-3 traits correlate with specific KH strategies: Machiavellians predominantly use evasive hiding, narcissists favor rationalized hiding, and psychopaths are more inclined to adopt a "playing dumb" strategy. Overall, most studies suggest a positive association between D-3 traits and KH. However, this relationship may vary when other factors are considered. For instance, narcissists typically exhibit low organizational commitment due to their self-centered nature (Foster et al., 2009). Nevertheless, aligning organizational goals with narcissists' aspirations can enhance their commitment and drive innovation (Cesinger et al., 2023). By appealing to their desire for status and legacy, such alignment may reduce their tendency to engage in KH.

Our review of the extant literature suggests that personality characteristics (e.g., Big-5 and D-3 traits), both positive and negative, play a significant role in KH. A recent systematic review of KH literature also highlighted a gap in research exploring the association between personality traits and KH across various contexts (Khizar et al., 2024). Against this background, this study investigates the interplay and specific mechanisms through which personality traits influence KH.

RQ2: To what extent do differences in personality characteristics (the Big Five traits and the Dark Triad traits) explain variations in KH?

Complexity theory and KHComplexity theory, initially developed in the physical and biological sciences, has since been applied to the social sciences. Anderson's (1999) seminal work facilitated its integration into organizational science research. The theory posits that complex systems consist of interconnected elements that interact nonlinearly and dynamically, resulting in emergent behaviors and outcomes that cannot be understood by examining individual aspects in isolation (Wallis, 2009). According to Levy (2000), it is "the study of complex, nonlinear, dynamic systems with feedback effects" (Levy, 2000, p. 68). Likewise, Urry (2005) noted that "relationships between variables can be nonlinear with abrupt switches occurring, so the same cause can, in specific circumstances, produce different effects" (Urry, 2005, p. 4).

Proponents of complexity theory argue that most causal conditions are neither sufficient nor necessary for an outcome to occur (Woodside et al., 2018). Instead, outcomes are shaped by various factors operating in tandem. These factors rarely (or differently) act in isolation and, depending on the context, the same conditions may yield contrasting effects (Furnari et al., 2021; Misangyi et al., 2017; Ordanini et al., 2014).

Complexity theory is grounded in three key tenets: (i) causal complexity (or conjunctural causation), whereby a single factor rarely causes an outcome; instead, outcomes depend on multiple interdependent factors, (ii) equifinality, which suggests that there are multiple pathways to achieve the same outcome, and (iii) asymmetrical relationships, which suggests that the factors contributing to the presence of an outcome are not necessarily the inverse of those leading to its absence. In the context of this study, complexity theory offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the causal mechanisms underlying KH in organizations. Rather than examining individual factors in isolation, complexity theory emphasizes examining the complex interactions among multiple factors, such as demographics and personality traits.

Building on the principles of complexity theory, this study investigates how various combinations of demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, education, and experience), Big-5 traits (openness, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism), and D-3 traits (psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism) contribute to KH behaviors among employees. In particular, we aimed to identify unique combinations of factors most significantly associated with KH rather than examining the isolated effects of each factor. We postulate that KH is not driven by a single personality trait or demographic factor. Instead, KH likely results from the complex interplay of demographic factors and personality characteristics. To address these complexities, we formulated the following research question and developed a comprehensive framework (Fig. 1):

RQ3: To what extent do differences in demographics (age, gender, education, and experience) and personality characteristics (Big-5 traits and Dark Triad traits) explain variations in KH?

Research methodsSample and proceduresThe hospitality industry attaches great importance to knowledge transfer and employee collaboration to maintain customer assurance and promote service innovations (Javed et al., 2017; Kim & Lee, 2013; Zhao et al., 2016). Therefore, it is important to investigate the dynamics of KH among hospitality sector employees. Our empirical setting is the South Punjab region of Pakistan. This is significant because various religious events (e.g., Chanan Peer Mela and Shah Shams), cultural activities (e.g., Jeep rally in Cholistan desert, and the palaces of the Nawabs), and sports arenas (e.g., National Cricket Stadiums) attract a large number of tourists from all over the world. To identify suitable research participants from the hospitality industry, we obtained a list of hotels functioning in the South Punjab region from the Pakistan Hotel Association (PHA) and a representative of a local chain of hotels and restaurants. Subsequently, the HR departments of these particular hotels and restaurants were contacted, and after obtaining the necessary permissions, the data were collected using self-administered questionnaires.

The current study took a rigorous approach to recruiting a diverse and representative sample of respondents from various operational departments within the hospitality industry, including front desk management, marketing, finance section, R&D, human resource management, and information technology. This approach was taken to ensure that the perspectives of employees working at different levels and areas of expertise are captured. This is also important due to the significance of communication and collaboration among employees in creating and delivering innovative services (Tang et al., 2015). Participation in the survey was voluntary, and questionnaires were distributed through the facilitation of each hotel's human resources department. We requested their contact numbers and email addresses to establish effective communication channels with employees. However, most respondents did not provide their personal contact information due to privacy and data security concerns. Instead, they shared the hotel's PTCL (Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited) landline numbers and official email addresses for further correspondence. To ensure the timely completion of the questionnaires, we gave telephonic reminders to encourage employees to complete and return the questionnaires. This approach helped maintaining an active and efficient data collection process, respecting employees' privacy concerns and following ethical considerations for handling research data. We also employed several techniques to reduce the common method variance bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). These include maintaining the confidentiality and anonymity of respondents and introducing a two-week interval between two waves of data collection for the ratings of personality traits and KH (Kaya & Karatepe, 2020; Luu, 2021; Podsakoff et al., 2003).

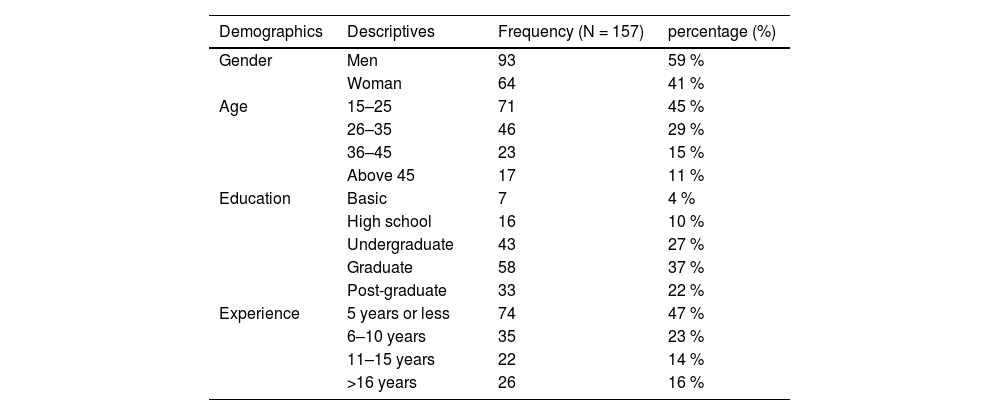

A total of 157 surveys were completed and utilized for further analysis, resulting in a response rate of 52.3 %. Demographic information (Table 1) of the respondents indicates that 59 % were male; the majority of employees were between the ages of 26 and 35, held bachelor's or master's degrees, and had varying levels of work experience.

Descriptive profile of the respondents.

| Demographics | Descriptives | Frequency (N = 157) | percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 93 | 59 % |

| Woman | 64 | 41 % | |

| Age | 15–25 | 71 | 45 % |

| 26–35 | 46 | 29 % | |

| 36–45 | 23 | 15 % | |

| Above 45 | 17 | 11 % | |

| Education | Basic | 7 | 4 % |

| High school | 16 | 10 % | |

| Undergraduate | 43 | 27 % | |

| Graduate | 58 | 37 % | |

| Post-graduate | 33 | 22 % | |

| Experience | 5 years or less | 74 | 47 % |

| 6–10 years | 35 | 23 % | |

| 11–15 years | 22 | 14 % | |

| >16 years | 26 | 16 % |

For the measurement of Big-5 personality traits, we utilized the 50-item scale suggested by Goldberg (1992) at a Five-point Likert scale, ranging from "strongly disagree" (1) to "strongly agree" (5). In addition, the scales for Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy are adapted from a 12-item scale by Jonason and Webster (2010). Next, our research explores how individual-level attributes, such as gender, age, education, and experience, shape employee attitudes and behaviours toward KH. Syed-Ikhsan and Rowland (2004) have carefully adapted and modified the demographic factors questionnaire items. For our outcome of interest (i.e., KH), we followed previous studies to utilize a three-item scale adapted from existing literature (Peng, 2013; Serenko & Bontis, 2016).

Analytical procedure – fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA)The current study explores the complex web of relationships between demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, education, and experience) and personality characteristics (i.e., Big 5 and D-3) associated with KH. However, traditional statistical techniques like multiple regression analysis (MRA) and structural equation modelling (SEM) have inherent limitations in unravelling complex interactions involving three or more causal conditions (Ragin, 2008; Woodside, 2013). To get beyond these restrictions, this study utilizes fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) as a dominant analytical tool (Roig-Tierno et al., 2017). FsQCA allows the identification of associations among various combinations of triggers and their effects on the results (Fiss, 2011).

In contrast to symmetrical analytical methods (e.g., SEM, MRA), fsQCA is an asymmetrical analytical technique originated by Ragin (2000)). The results obtained by fsQCA reflect the essential principles of complexity theory as follows: i) fsQCA reveals that the variables which appear to cause an outcome in one configuration may not have the same relationship or may even have an opposite effect in another configuration (asymmetrical relationships); ii) fsQCA demonstrates that there are multiple paths (or combinations of variables) that can lead to the same outcome (equifinality); iii) fsQCA highlights that there are multiple factors that may interact (or combined) to cause an outcome (causal complexity or conjunctural relationship). Unlike traditional regression-based (net-effects) methods, fsQCA identifies multiple configurations of causal conditions leading to the outcome by considering conjunctural causation, equifinality, and asymmetric associations. Notably, fsQCA in business management literature has gained popularity in recent years in understanding the various complex organizational phenomena (Kumar et al., 2022). Therefore, the utilization of fsQCA is justified in this study because the complex patterns of causal interrelationships between sources of KH, such as personality traits (Big-5 and d-3) and demographic factors (gender, age, education, and experience) require advanced analytical methods such as fsQCA (Woodside, 2013).

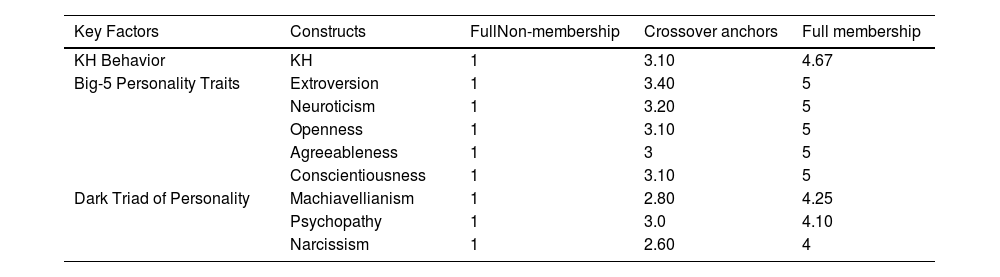

Analysis and resultsData calibrationData calibration is a crucial step in fsQCA, involving the transformation of raw data for all causal conditions and the outcome of interest into fuzzy values ranging from 0 to 1 (Ragin, 2008). In this study, we selected three reference points—full membership, crossover, and full non-membership—to calibrate the data (Kallmuenzer et al., 2019; Palmer et al., 2019). We used the 90th, 50th, and 10th percentiles as anchors for full membership, crossover points, and full non-membership, respectively, for all variables except gender (which is dichotomous). Table 2 presents the detailed calibration thresholds.

Calibration of multiple conditions and outcome variables.

| Key Factors | Constructs | FullNon-membership | Crossover anchors | Full membership |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KH Behavior | KH | 1 | 3.10 | 4.67 |

| Big-5 Personality Traits | Extroversion | 1 | 3.40 | 5 |

| Neuroticism | 1 | 3.20 | 5 | |

| Openness | 1 | 3.10 | 5 | |

| Agreeableness | 1 | 3 | 5 | |

| Conscientiousness | 1 | 3.10 | 5 | |

| Dark Triad of Personality | Machiavellianism | 1 | 2.80 | 4.25 |

| Psychopathy | 1 | 3.0 | 4.10 | |

| Narcissism | 1 | 2.60 | 4 |

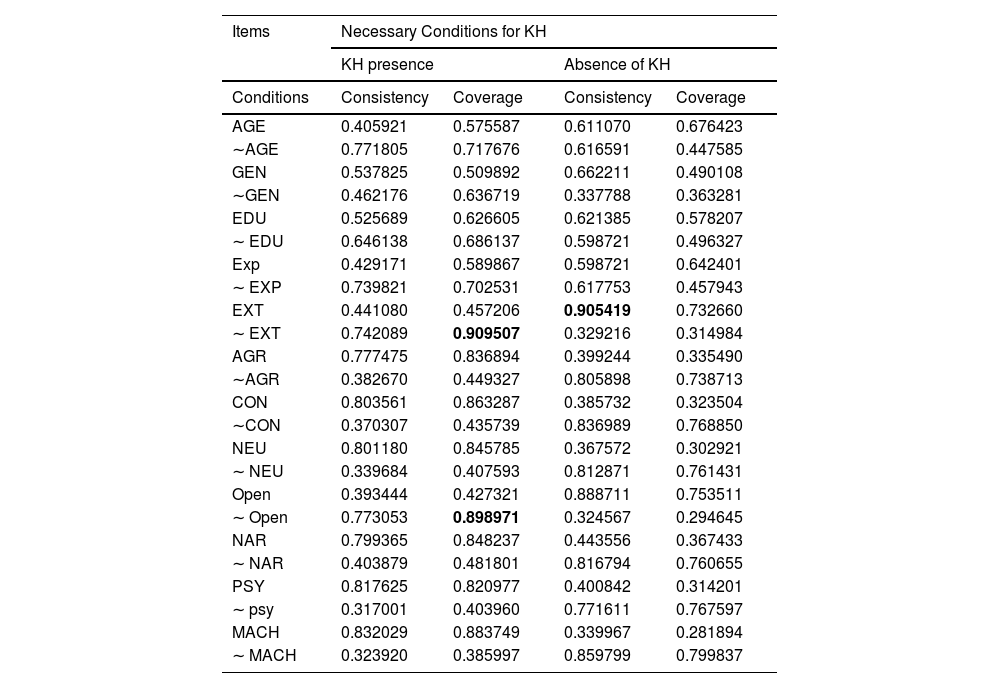

By utilizing fsQCA software, we performed two key analyses: (i) necessity analysis, and (ii) sufficiency analysis. A necessary condition refers to a condition that must exist for the outcome of interest to occur, while sufficient conditions are the conditions or configurations that are sufficient to produce the result.

Necessity analysisA condition is considered “necessary” if its relative coverage and consistency are equal to or greater than 0.5 and 0.9, respectively (Pappas et al., 2020; Schneider & Wagemann, 2010). Table 3 below presents the findings of necessity analysis, offering valuable insights into the necessary conditions for both the presence and absence of KH. Our analysis revealed two necessary conditions for the presence of KH, namely low in openness (∼OP) and low in extraversion (∼EXT). On the other hand, the EXT is the only necessary condition found for the absence of KH. A consistency value of 0.9 or higher indicates that these conditions are "almost always necessary" for the presence (or absence) of KH; thus, it is also an essential component in the subsequent analysis of sufficient conditions.

Analysis of necessary conditions for results.

| Items | Necessary Conditions for KH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KH presence | Absence of KH | |||

| Conditions | Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage |

| AGE | 0.405921 | 0.575587 | 0.611070 | 0.676423 |

| ∼AGE | 0.771805 | 0.717676 | 0.616591 | 0.447585 |

| GEN | 0.537825 | 0.509892 | 0.662211 | 0.490108 |

| ∼GEN | 0.462176 | 0.636719 | 0.337788 | 0.363281 |

| EDU | 0.525689 | 0.626605 | 0.621385 | 0.578207 |

| ∼ EDU | 0.646138 | 0.686137 | 0.598721 | 0.496327 |

| Exp | 0.429171 | 0.589867 | 0.598721 | 0.642401 |

| ∼ EXP | 0.739821 | 0.702531 | 0.617753 | 0.457943 |

| EXT | 0.441080 | 0.457206 | 0.905419 | 0.732660 |

| ∼ EXT | 0.742089 | 0.909507 | 0.329216 | 0.314984 |

| AGR | 0.777475 | 0.836894 | 0.399244 | 0.335490 |

| ∼AGR | 0.382670 | 0.449327 | 0.805898 | 0.738713 |

| CON | 0.803561 | 0.863287 | 0.385732 | 0.323504 |

| ∼CON | 0.370307 | 0.435739 | 0.836989 | 0.768850 |

| NEU | 0.801180 | 0.845785 | 0.367572 | 0.302921 |

| ∼ NEU | 0.339684 | 0.407593 | 0.812871 | 0.761431 |

| Open | 0.393444 | 0.427321 | 0.888711 | 0.753511 |

| ∼ Open | 0.773053 | 0.898971 | 0.324567 | 0.294645 |

| NAR | 0.799365 | 0.848237 | 0.443556 | 0.367433 |

| ∼ NAR | 0.403879 | 0.481801 | 0.816794 | 0.760655 |

| PSY | 0.817625 | 0.820977 | 0.400842 | 0.314201 |

| ∼ psy | 0.317001 | 0.403960 | 0.771611 | 0.767597 |

| MACH | 0.832029 | 0.883749 | 0.339967 | 0.281894 |

| ∼ MACH | 0.323920 | 0.385997 | 0.859799 | 0.799837 |

Our analysis to identify sufficient conditions involved several steps. Following standard procedures (Fiss, 2011; Ragin, 2008), we constructed a truth table with 2k rows, where 'k' denotes the number of causal conditions, and every row denotes a possible combination of all conditions, often referred to as 'pathways' or 'recipe' or 'prescriptions' or 'configurations' (e.g., H.M.U. Khizar et al., 2024; Woodside, 2014; Greckhamer et al., 2018). Given that there are 12 causal conditions, including Big-5, d-3, and demographic characteristics (n = 4), the truth table highlighted 4096 possible combinations (212 = 4096). However, given this complexity, we initially performed separate analyses for personality traits and demographic characteristics before running the comprehensive examination to identify configurations associated with KH.

After constructing the truth table, the logical minimization process reduced the number of rows in the truth table based on their frequency and consistency values (Fiss, 2011; Ragin, 2008). The frequency refers to the number of observations for every possible combination, while the consistency measures the extent to which the cases are consistent with the set of theoretical relations defined in the solution (Fiss, 2011). We set a consistency cut-off value of 0.80 and a minimum frequency threshold of 2 cases. Finally, fsQCA generates three types of solutions, namely, complex solutions (without logical residuals), intermediate solutions (with partial logical residuals), and parsimonious solutions (with all logical residuals). In particular, intermediate solutions are generally considered preferable to both complex and parsimonious solutions (Ragin, 2009). After obtaining the results, we classified the conditions as core or peripheral. Core conditions are those which have a strong causal relevance, appearing in both "intermediate" and "parsimonious" solutions, while peripheral conditions demonstrate a weak causal relevance, appearing only in the intermediate solution (Fiss, 2011; Kourouthanassis et al., 2017).

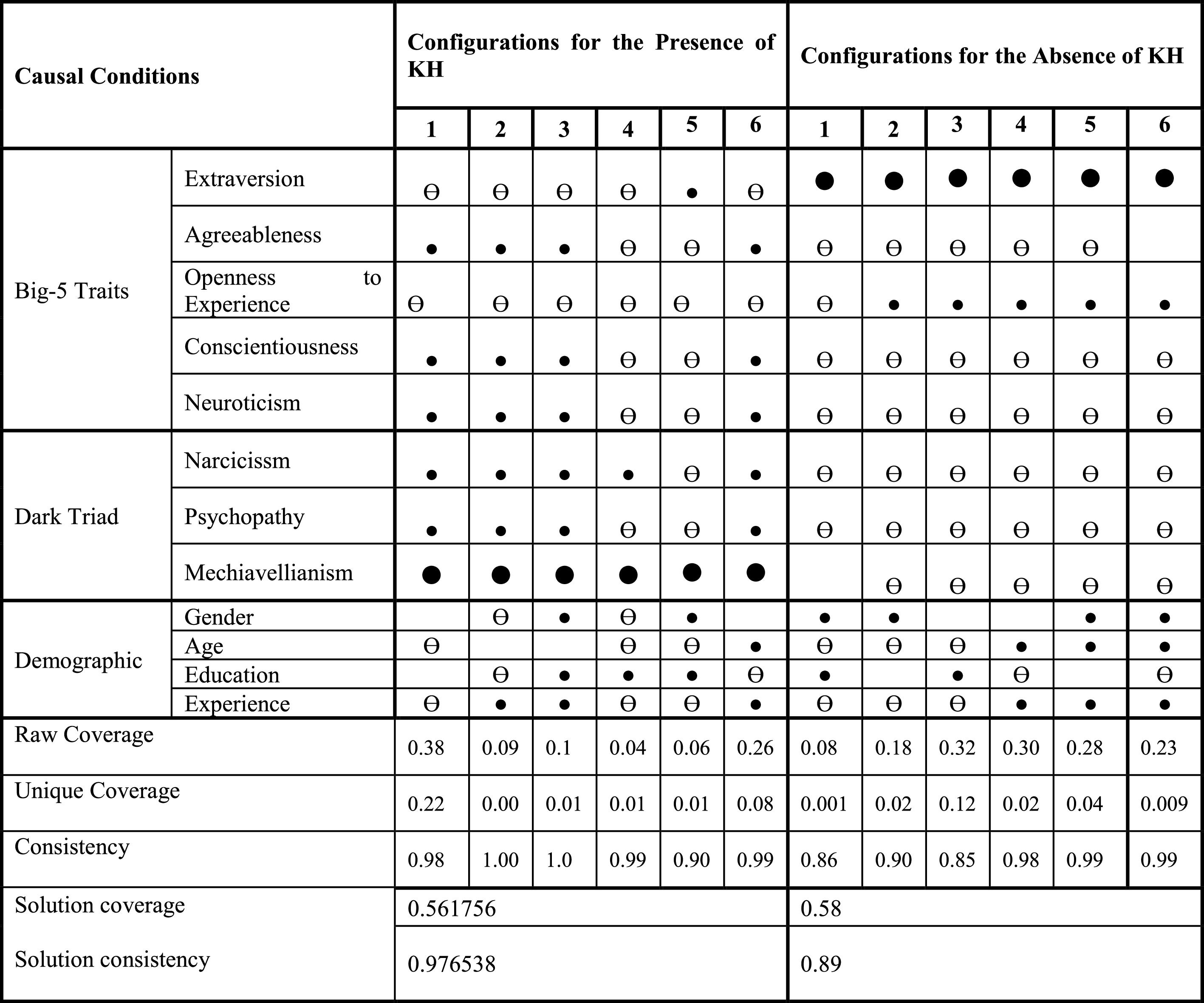

Solutions: configurations related to KHOur analysis identified various configurations associated with the presence (high) and absence (low) of KH. Both solutions (KH and ∼KH) highlight the relevance of their contributions to the identified configurations in the parsimonious and intermediate solutions. Solution consistency represents the alignment between the identified configurations and the outcomes, while solution coverage indicates the proportion of outcomes explained by the identified configurations (Ragan, 2008). Furthermore, raw coverage reflects the proportion (or percentage) of the outcome explained by a specific configuration, whereas unique coverage measures the proportion of the outcome explained exclusively by a particular configuration (Ragin, 2008; Woodside et al., 1999; Zhang, 2012).

We adopted the notations commonly used in fsQCA research (e.g., Fiss, 2011; Ragin & Fiss, 2008) to visually represent the presence, absence, and importance of various conditions. A small black circle (●) represents the presence of a condition. A crossed-out black circle (¿) indicates the absence of a condition. An empty cell indicates a "don't care" situation, meaning the predictor may or may not be present. Larger circles represent core conditions, while smaller circles indicate peripheral conditions with weaker causal relevance.

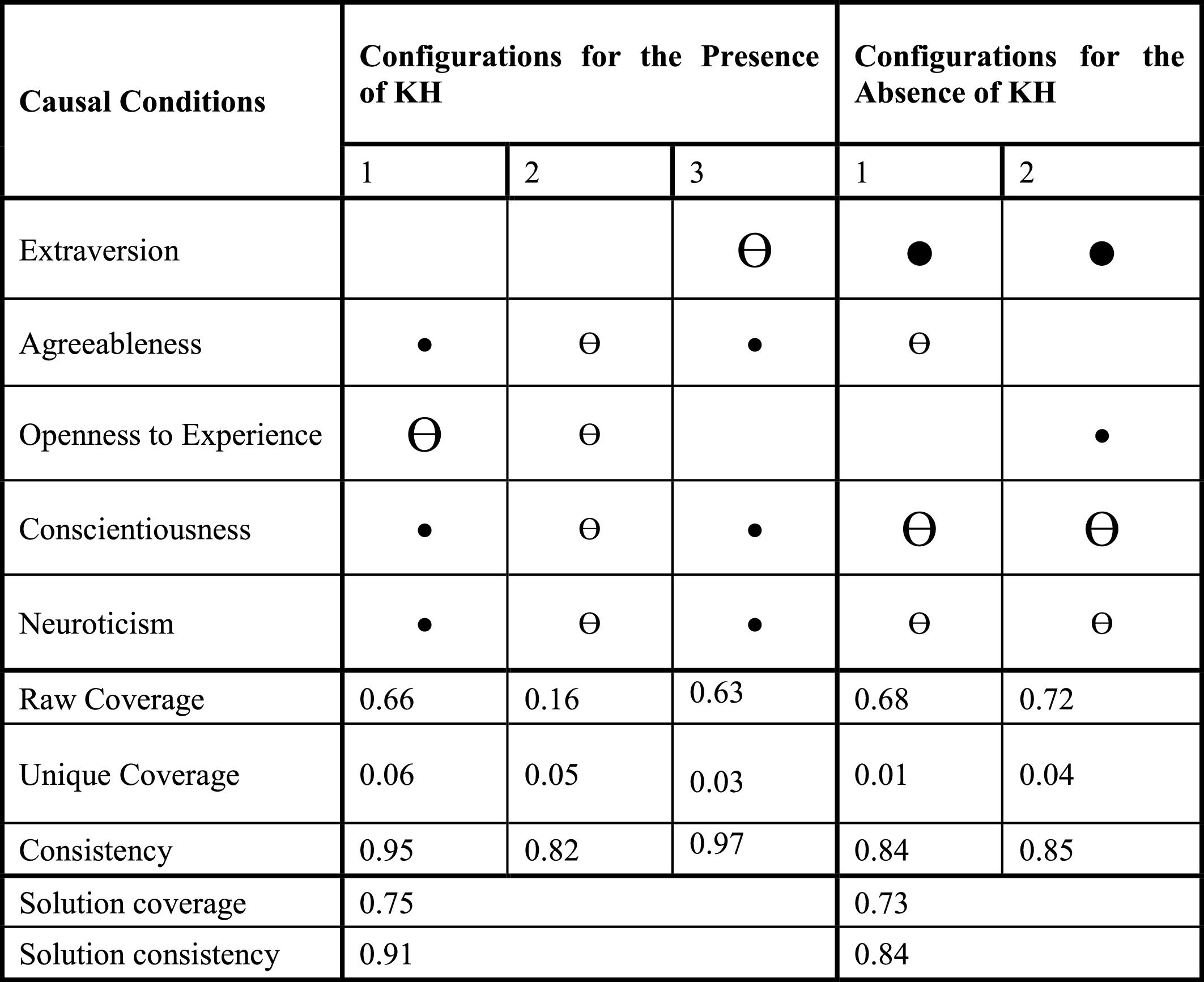

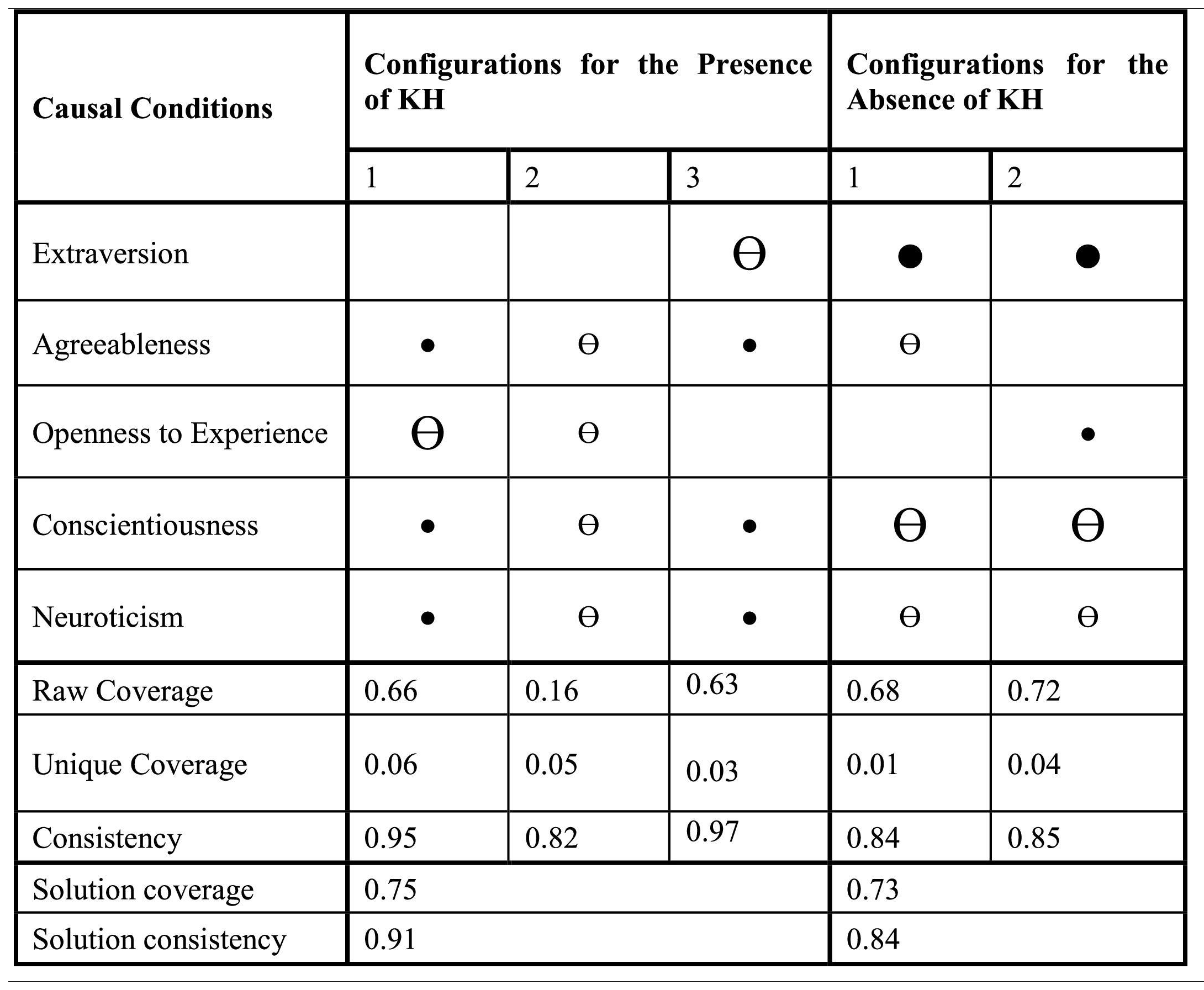

Configurations of big-5 personality traitsTable 4 presents the solutions for the presence (three configurations) and absence (two configurations) of KH associated with the Big-5 personality traits. Regarding the presence of KH, critical traits included low extraversion and low openness, combined with either high or low levels of other traits. Conversely, the absence of KH was characterized by configurations involving high extraversion and high transparency, alongside low conscientiousness and low neuroticism.

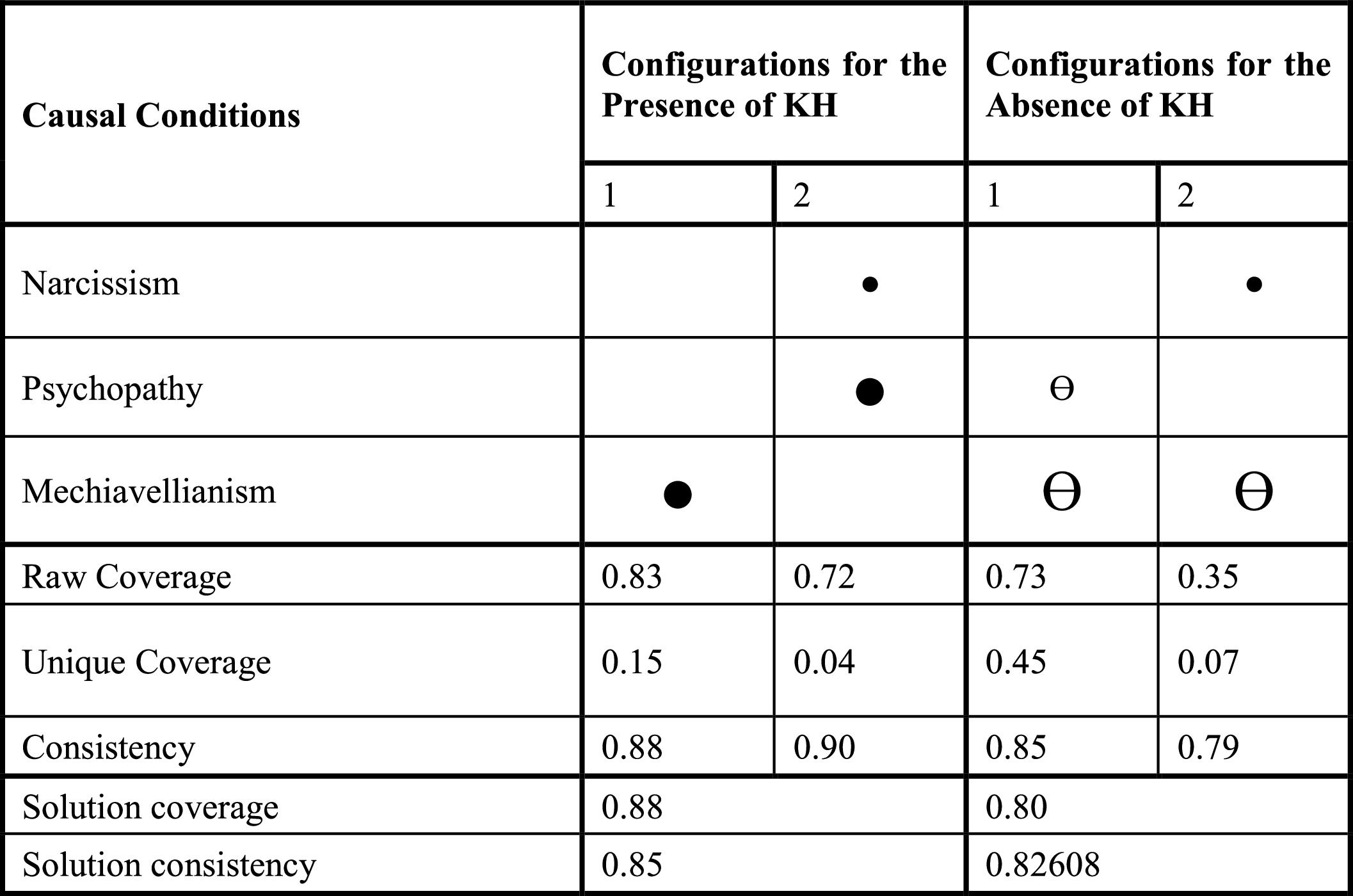

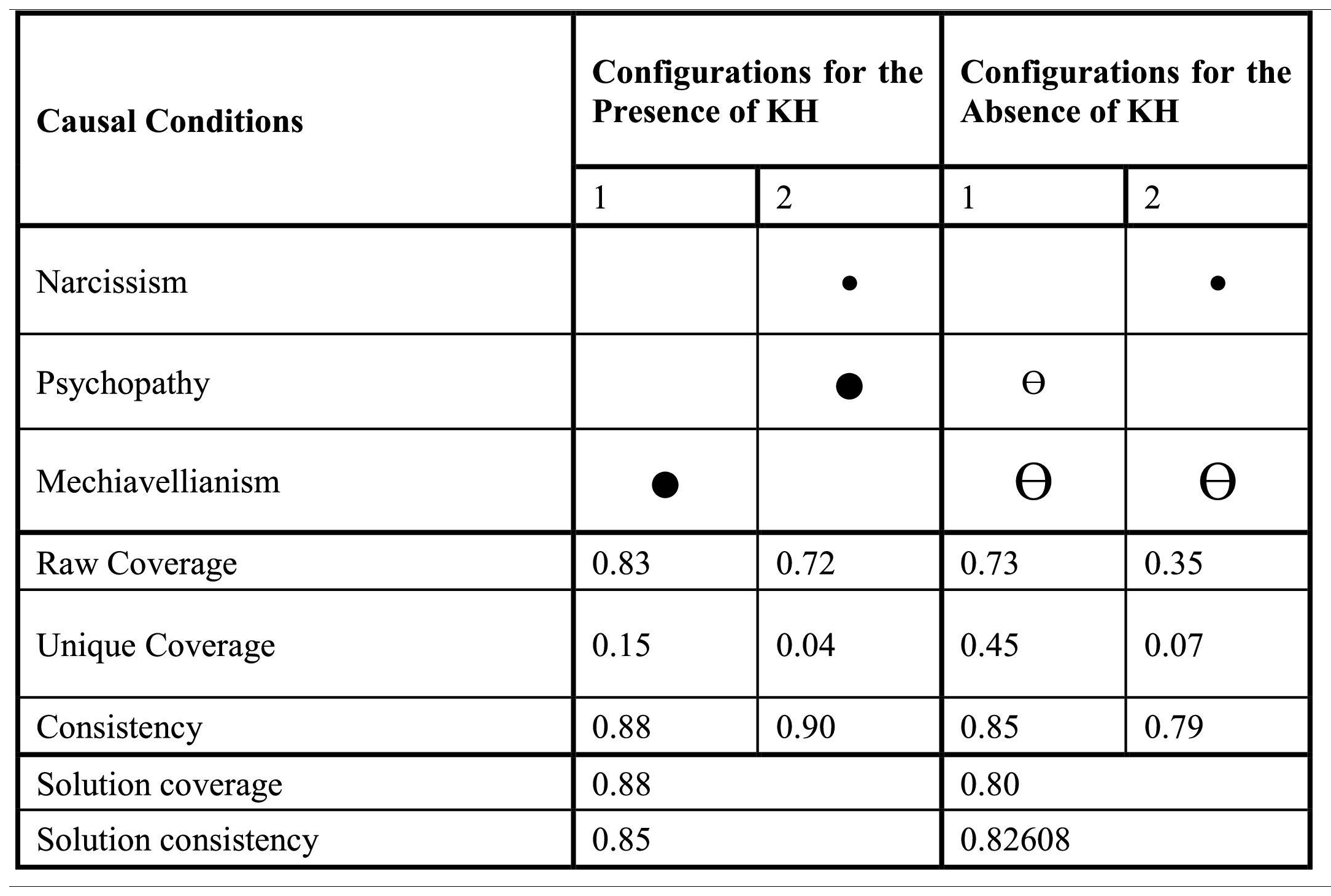

Configurations ofD-3 personality traitsTable 5 illustrates the configurations identified for psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism (D-3 traits). Our analysis revealed that psychopathy and Machiavellianism were significantly associated with KH, regardless of the presence or absence of narcissism. However, low Machiavellianism emerged as the core condition for the absence of KH. Notably, individuals who were high in narcissism and low in Machiavellianism were less likely to engage in KH.

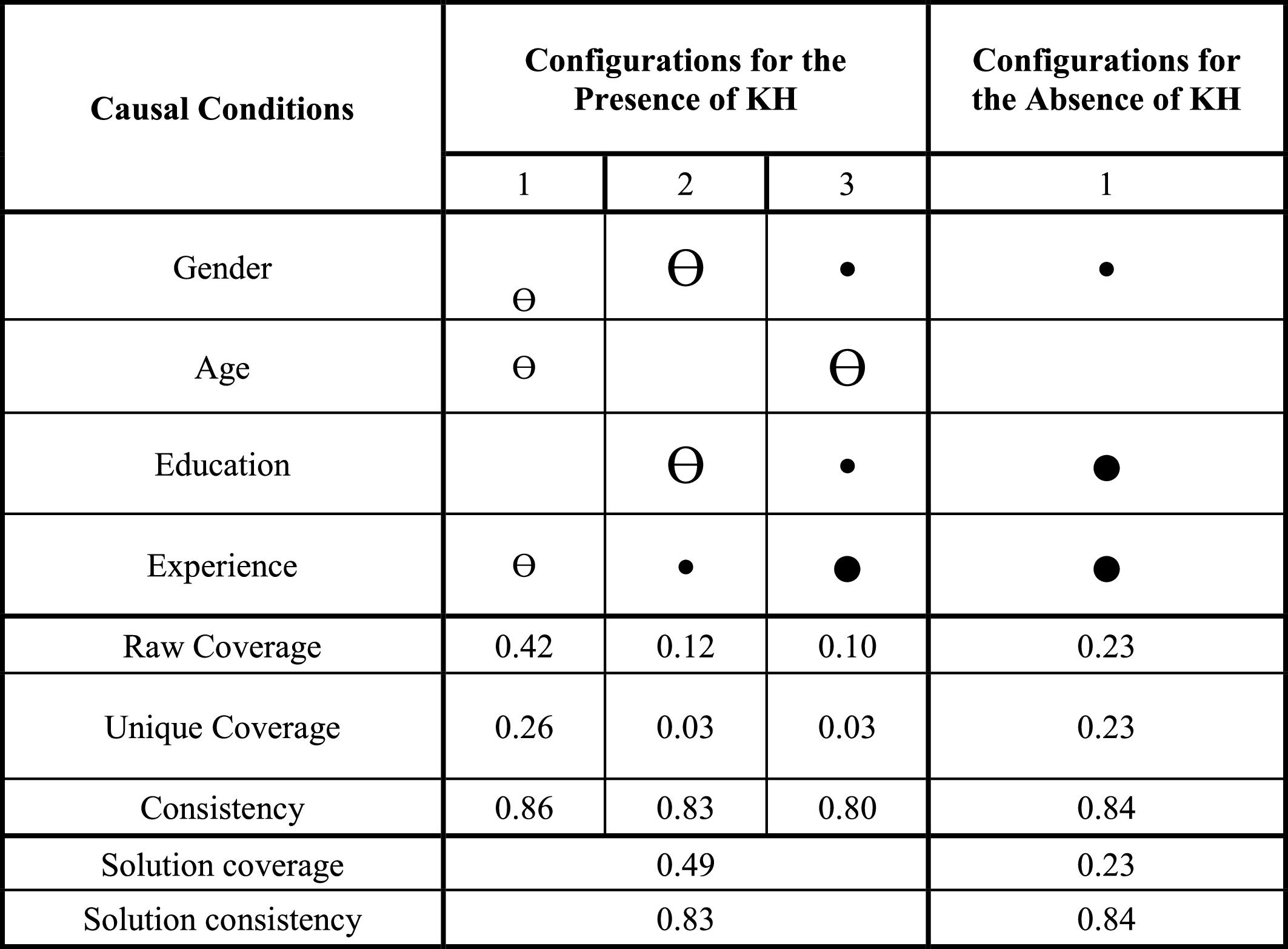

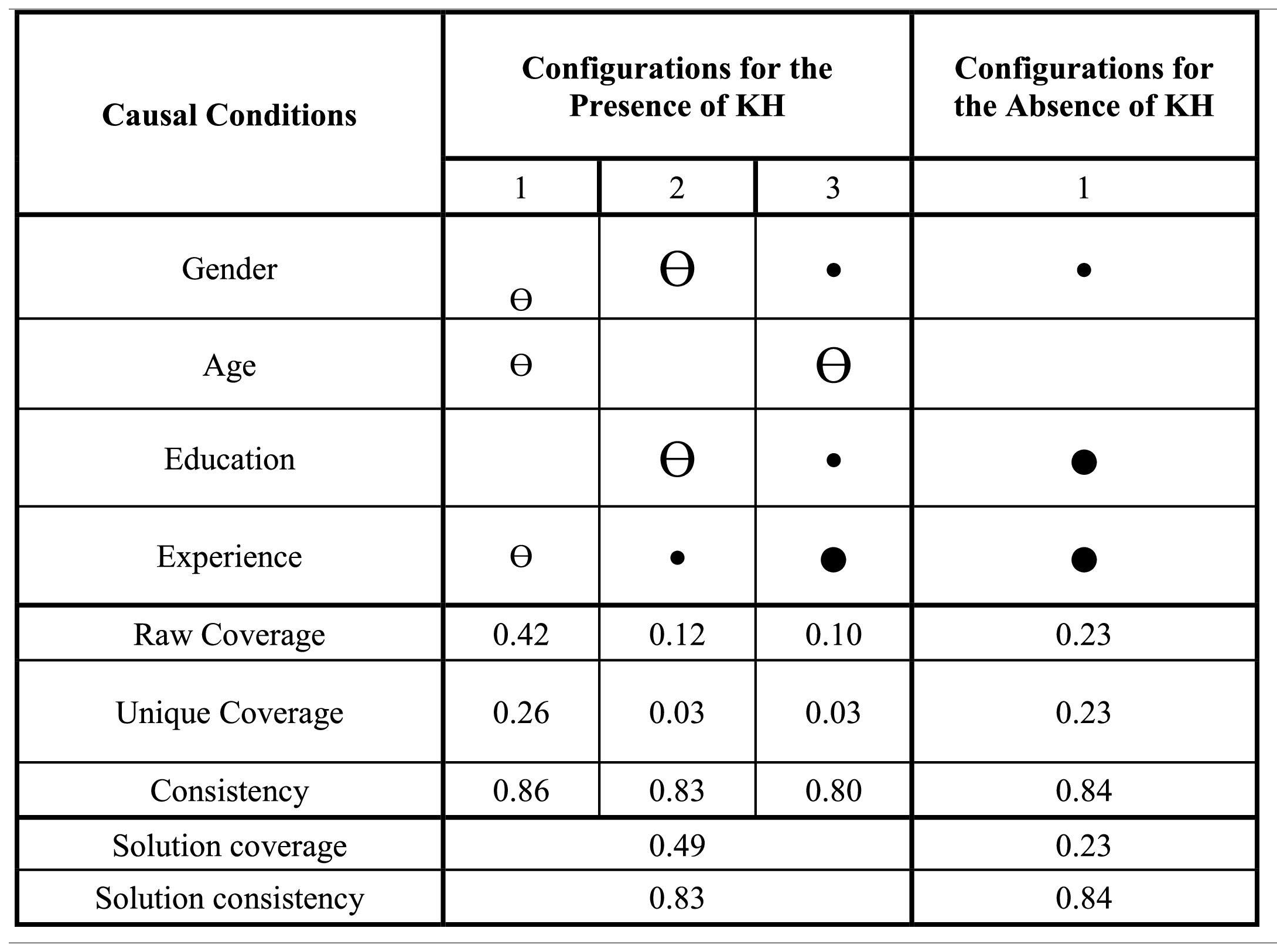

Demographic orientations toward KHTable 6 presents the configurations of four demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, education, and experience) associated with KH. For the presence of KH, we observed that younger employees with lower levels of education and less experience were more prone to KH. In addition, experienced females with lower levels of education demonstrated a tendency toward KH. Interestingly, younger male employees with higher levels of education and experience engaged in KH as well. In contrast, employee education and experience were significantly associated with the absence of KH, suggesting that higher educational attainment and accumulated work experience reduce KH behaviors.

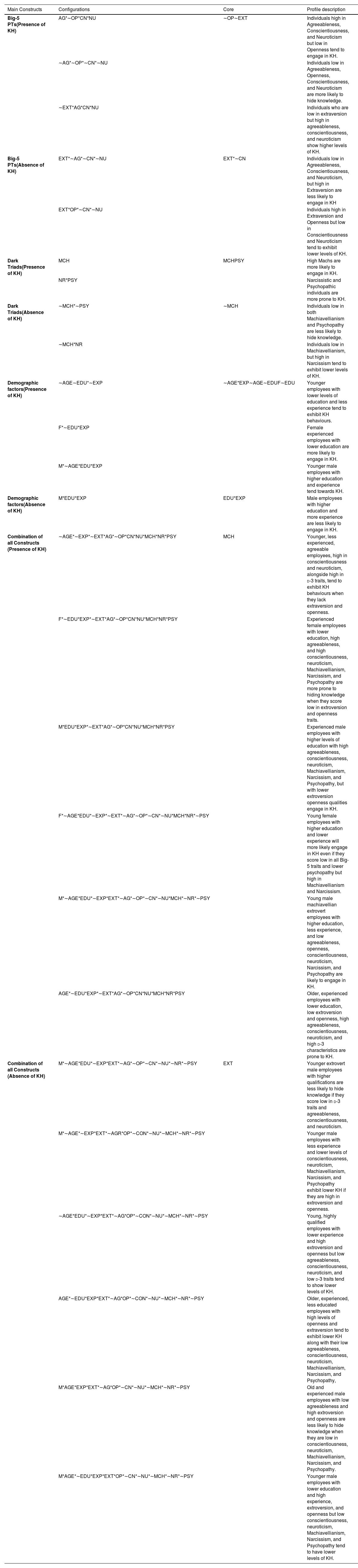

Interplay of big-5 traits,D-3, and demographic factorsA comprehensive analysis of the interplay between personality traits and demographic characteristics revealed six configurations related to the presence and absence of KH, as shown in Table 7. Key findings indicate that Machiavellianism emerged as the core condition driving the presence of KH, whereas extraversion was identified as the core condition associated with the absence (or low levels) of KH. Table 7 shows how these personality traits interact with demographic factors to produce various configurations.

Interpretation of all configurationsTo facilitate a more nuanced understanding, Table 8 presents a concise overview of the interplay between personality traits, demographic characteristics, and KH.

Interpretation of all configuration associated with KH – interplay of Big-5, D-3 and demographic characteristics.

| Main Constructs | Configurations | Core | Profile description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Big-5 PTs(Presence of KH) | AG*∼OP*CN*NU | ∼OP∼EXT | Individuals high in Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Neuroticism but low in Openness tend to engage in KH. |

| ∼AG*∼OP*∼CN*∼NU | Individuals low in Agreeableness, Openness, Conscientiousness, and Neuroticism are more likely to hide knowledge. | ||

| ∼EXT*AG*CN*NU | Individuals who are low in extraversion but high in agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism show higher levels of KH. | ||

| Big-5 PTs(Absence of KH) | EXT*∼AG*∼CN*∼NU | EXT*∼CN | Individuals low in Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Neuroticism, but high in Extraversion are less likely to engage in KH |

| EXT*OP*∼CN*∼NU | Individuals high in Extraversion and Openness but low in Conscientiousness and Neuroticism tend to exhibit lower levels of KH. | ||

| Dark Triads(Presence of KH) | MCH | MCHPSY | High Machs are more likely to engage in KH. |

| NR*PSY | Narcissistic and Psychopathic individuals are more prone to KH. | ||

| Dark Triads(Absence of KH) | ∼MCH*∼PSY | ∼MCH | Individuals low in both Machiavellianism and Psychopathy are less likely to hide knowledge. |

| ∼MCH*NR | Individuals low in Machiavellianism, but high in Narcissism tend to exhibit lower levels of KH. | ||

| Demographic factors(Presence of KH) | ∼AGE∼EDU*∼EXP | ∼AGE*EXP∼AGE∼EDUF∼EDU | Younger employees with lower levels of education and less experience tend to exhibit KH behaviours. |

| F*∼EDU*EXP | Female experienced employees with lower education are more likely to engage in KH. | ||

| M*∼AGE*EDU*EXP | Younger male employees with higher education and experience tend towards KH. | ||

| Demographic factors(Absence of KH) | M*EDU*EXP | EDU*EXP | Male employees with higher education and more experience are less likely to engage in KH. |

| Combination of all Constructs (Presence of KH) | ∼AGE*∼EXP*∼EXT*AG*∼OP*CN*NU*MCH*NR*PSY | MCH | Younger, less experienced, agreeable employees, high in conscientiousness and neuroticism, alongside high in d-3 traits, tend to exhibit KH behaviours when they lack extraversion and openness. |

| F*∼EDU*EXP*∼EXT*AG*∼OP*CN*NU*MCH*NR*PSY | Experienced female employees with lower education, high agreeableness, and high conscientiousness, neuroticism, Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy are more prone to hiding knowledge when they score low in extroversion and openness traits. | ||

| M*EDU*EXP*∼EXT*AG*∼OP*CN*NU*MCH*NR*PSY | Experienced male employees with higher levels of education with high agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy, but with lower extroversion openness qualities engage in KH. | ||

| F*∼AGE*EDU*∼EXP*∼EXT*∼AG*∼OP*∼CN*∼NU*MCH*NR*∼PSY | Young female employees with higher education and lower experience will more likely engage in KH even if they score low in all Big-5 traits and lower psychopathy but high in Machiavellianism and Narcissism. | ||

| M*∼AGE*EDU*∼EXP*EXT*∼AG*∼OP*∼CN*∼NU*MCH*∼NR*∼PSY | Young male machiavellian extrovert employees with higher education, less experience, and low agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy are likely to engage in KH. | ||

| AGE*∼EDU*EXP*∼EXT*AG*∼OP*CN*NU*MCH*NR*PSY | Older, experienced employees with lower education, low extroversion and openness, high agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and high d-3 characteristics are prone to KH. | ||

| Combination of all Constructs (Absence of KH) | M*∼AGE*EDU*∼EXP*EXT*∼AG*∼OP*∼CN*∼NU*∼NR*∼PSY | EXT | Younger extrovert male employees with higher qualifications are less likely to hide knowledge if they score low in d-3 traits and agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism. |

| M*∼AGE*∼EXP*EXT*∼AGR*OP*∼CON*∼NU*∼MCH*∼NR*∼PSY | Younger male employees with less experience and lower levels of conscientiousness, neuroticism, Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy exhibit lower KH if they are high in extroversion and openness. | ||

| ∼AGE*EDU*∼EXP*EXT*∼AG*OP*∼CON*∼NU*∼MCH*∼NR*∼PSY | Young, highly qualified employees with lower experience and high extroversion and openness but low agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and low d-3 traits tend to show lower levels of KH. | ||

| AGE*∼EDU*EXP*EXT*∼AG*OP*∼CON*∼NU*∼MCH*∼NR*∼PSY | Older, experienced, less educated employees with high levels of openness and extraversion tend to exhibit lower KH along with their low agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy, | ||

| M*AGE*EXP*EXT*∼AG*OP*∼CN*∼NU*∼MCH*∼NR*∼PSY | Old and experienced male employees with low agreeableness and high extroversion and openness are less likely to hide knowledge when they are low in conscientiousness, neuroticism, Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy. | ||

| M*AGE*∼EDU*EXP*EXT*OP*∼CN*∼NU*∼MCH*∼NR*∼PSY | Younger male employees with lower education and high experience, extroversion, and openness but low conscientiousness, neuroticism, Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy tend to have lower levels of KH. |

*Note: These profiles are interpreted based on the configurations identified from the analysis on the sample data of this study. These may vary in large samples, in combination with other factors, and in different contexts.

Understanding the fundamental causes of KH is crucial for both academics and practitioners. Drawing on complexity theory, this study utilizes fsQCA to investigate the configurations of personality traits (i.e., the Big-5 and d-3) and demographic factors (i.e., age, gender, education, and experience) that drive KH behaviors. Our findings reveal various configurations of employee personality traits and demographic factors associated with both the absence and presence of KH. These findings underscore the complexity of KH, emphasizing that it arises from a mix of demographic traits and personality characteristics (Balakrishnan et al., 2019).

From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to and extends the existing discourse on individual differences, organizational behavior, and hospitality. Regarding the link between demographic factors and KH (Andreeva & Zappa, 2023; Lazazzara & Za, 2019; Liu & Dong, 2022; Zhang et al., 2023), our findings indicate that younger employees with lower levels of education and experience are more likely to engage in KH. Additionally, experienced females with low educational levels exhibit higher tendencies for KH, while experienced males with higher educational levels are less likely to engage in such behaviors.

The negative association between employee experience and KH can be explained by the notion that experienced employees may possess a stronger sense of responsibility and professionalism, along with a greater commitment to their organizations. Similarly, the inverse relationship between education and KH may stem from the idea that highly educated employees value knowledge exchange, are more ethically inclined, or are more motivated to contribute to organizational success.

This study further underscores the predictive power of the Big-5 and D-3 personality traits in explaining KH, contributing to the growing body of literature on the role of individual differences in shaping workplace attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Douglas & Martinko, 2001; Sharma & Devi, 2011; Zhang et al., 2023). Our findings reveal that individuals with low openness but high agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism are more likely to engage in KH. Conversely, individuals high in extraversion and openness, combined with low agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism, are less likely to engage in KH.

We also found that individuals exhibiting D-3 traits, particularly Machiavellianism, are more prone to KH, with Machiavellians demonstrating the highest propensity. Conversely, employees with low levels of Machiavellianism and psychopathy are less likely to hide knowledge. Interestingly, we observed that high levels of narcissism, when combined with low levels of Machiavellianism, could lead to reduced KH. This finding aligns with previous research identifying narcissists as visionaries driven by a passion for innovation (Campbell et al., 2011). Moreover, the positive relationship between narcissism and organizational normative commitment suggests that narcissists, when strongly connected to their organizations, may engage in knowledge-sharing to reinforce their status and influence (Cesinger et al., 2023).

Drawing on the parallels between complexity theory, the configurational approach, and qualitative comparative analysis (e.g., Byrne, 2005; Di Paola et al., 2025; Misangyi et al., 2017; Woodside, 2014), our findings support these foundational principles. By comprehensively examining the individual differences associated with KH behaviors, our analysis reinforces the core tenets of complexity and configurational approaches, namely causal complexity, equifinality, and asymmetry. Specifically, this study identifies multiple factors, such as personality traits and demographic characteristics, associated with KH. These findings reveal a nonlinear relationship, highlighting that the same factors associated with the presence of KH can also lead to its absence, depending on the configuration of conditions.

Our findings have relevance across various disciplines and industries. For academics and practitioners interested in the role of the Big-5 and d-3 traits in entrepreneurship (Kraus et al., 2020; Salmony & Kanbach, 2022), this study offers insights into how personality traits influence knowledge behaviors. Since knowledge sharing is critical for fostering innovation and competitive advantage in entrepreneurial ventures, understanding these influences can help create environments that encourage open communication and collaboration. In this context, managerial cognitive styles (Kryeziu et al., 2024) and knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (Hernández-Linares et al., 2024) can enhance firm performance by mitigating the adverse effects of KH.

Similarly, our findings align with prior research emphasizing the importance of effective knowledge management in enhancing organizational performance (e.g., Wuytens et al., 2024; Zaim et al., 2022). These insights are particularly relevant for service-oriented industries, such as hospitality, where efficient knowledge management directly impacts customer satisfaction and operational efficiency. By understanding the drivers of KH behaviors, hospitality managers can design better training programs and interventions to promote transparency and collaboration, ultimately enhancing organizational outcomes.

From a practical viewpoint, our findings have important implications and recommendation for organizations seeking to reduce KH behaviour among their employees. Managers and organizations can develop targeted interventions to reduce this deviant behaviour by identifying specific demographic and personality traits associated with such behaviour. In particular, managers should pay attention to specific personality traits (e.g., Big-5, D-3) and individual characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education) when dealing with KH (or to promote a culture of knowledge sharing) in their organizations. Among others, factors such as neuroticism, machiavellianism, psychopathy, and varying levels of employee age, gender, and education are identified as significant factors linked to the presence of KH. On the other hand, our findings underscored extraversion as key characteristics associated with the absence (or low levels) of KH. Therefore, HR managers may consider developing screening tests to evaluate individual personality traits and demographic factors during hiring.

Moreover, based on these insights, supervisors and managers may allocate their employees to tasks requiring a higher (or lower) knowledge exchange among members. Our findings also suggest that employees' extraversion, level of education, and openness are important conditions associated with the lower tendency to engage in KH. Managers can leverage this insight by promoting a work environment that values continuous learning, encourages open communication, and fosters a knowledge exchange culture among employees. By emphasizing these positive attributes and creating a supportive atmosphere that values knowledge sharing, managers can reduce instances of KH within their teams and organizations. Besides, organizations can also develop tailored training programs that focus on increasing ethical behaviour and openness to experience among employees.

ConclusionConsidering the complex dynamics of individual differences and KH, this study offers insights into the individual-level antecedents of KH. In particular, we found how different configurations of demographic factors (i.e., age, gender, education, and experience), Big-5 (i.e., extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, conscientiousness, and openness), and D-3 traits (i.e., narcissism, psychopathy, and machiavellieanism) are associated with employees' KH. Instructively, this study identified several individual-level profiles related to KH.

Like any research study, current research has some limitations that warrant further research. First, our empirical context comprises employees working in the hospitality sector in the southern Punjab province of Pakistan. Given that the generalization of research findings is one of the primary concerns of any research (Rao et al., 2021), it should be further tested in other industrial (e.g., healthcare, education, manufacturing), geographical (e.g., western or developed countries), and cultural (e.g., uncertainty avoidance, individualism) contexts. For instance, cross-cultural differences (e.g., power distance and collectivism) can be examined to identify configurations leading to KH (Hossain et al., 2022). Moreover, future studies can also take into account additional contextual and environmental aspects to develop a middle-range theory that is significantly context-specific.

Second, our study did not distinguish among different typologies and dimensionalities of KH. Scholars have suggested that KH can apply to both tacit knowledge—such as personal expertise, skills, or know-how—and explicit knowledge, which is more formalized and codifiable (e.g., Duan et al., 2022). Moreover, Anand et al. (2023) highlighted that “there is scant evidence to suggest that the type of knowledge (tacit or explicit) sought contributes to increased or decreased KH behaviour today” (p. 1449). Future studies may examine various individual-level configurations associated with varying types of knowledge (e.g., tacit vs. explicit) and KH behaviours (e.g., playing dumb, evasive hiding, and rationalized hiding). Third, our study considered only some of the demographic and personality models available (i.e., Big-5, and D-3) to examine individual differences associated with KH. Future studies might explore other personality traits and/or individual-level characteristics to identify how employees’ distinct profiles link with KH or other workplace attitudes and behaviours.

Fourth, the findings of our study are based on a limited sample within a specialized context. Future researchers may consider investigating these dynamics on larger samples of employees (or top management) working in various functional departments (e.g., marketing and finance) and other types of businesses. Such an investigation would contribute to the existing literature by comparing and contrasting the present study's findings to examine any similarities (or differences) in the identified configurations. Finally, scholars have suggested that ranking or categorization in the hospitality sector (e.g., hotels and restaurants) is essential to attaining the potential effect of the study (Akhtar et al., 2022). However, future research can consider accounting for such ranking and categorization to gauge the differences of identified configurations based on these rankings (e.g., local, 1 star or 5 stars, etc.).

CRediT authorship contribution statementAndreas Kallmuenzer: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration. Rashid Khurshid: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Hafiz Muhammad Usman Khizar: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Conceptualization. Jingbo Yuan: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources.

This research ensures to maintain the anonymity of individuals and ensures no personal data or personally sensitive data are identifiable.