A 61-year-old man, with history of nephrolithiasis and frequent urinary tract infections, was admitted to the intensive care unit for sepsis secondary to acute pyelonephritis. He was not taking any personal medication and denied ever using alcohol, any herbal or folk remedies, and over-the-counter agents, including acetaminophen and salicylates. Moreover, there was no history of recent surgery or blood transfusions. The patient initiated empirical antibiotic treatment with piperacillin/tazobactam (PT) 2.25g IV every 6h (adjusted according to glomerular filtration rate) based on results of previous antibiogram. PT has not been previously used. Urine and blood culture tested positive for Escherichia coli. No other drugs were administered, except dipyrone, heparin sodium and folic acid. Four days after PT was introduced, he developed pruritus and a generalized rash. Physical examination was remarkable only for a generalized rash, jaundice in sclera and skin, with no peripheral lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory tests are shown in Table 1a. Serological screening for viral hepatitis, including hepatitis A, B, C and E viruses, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and herpes simplex virus, were negative. Hepatitis B virus DNA and hepatitis C and E virus RNA were not detected in the peripheral blood. Search for autoimmune liver disorders was negative. Abdominal sonography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography were unremarkable.

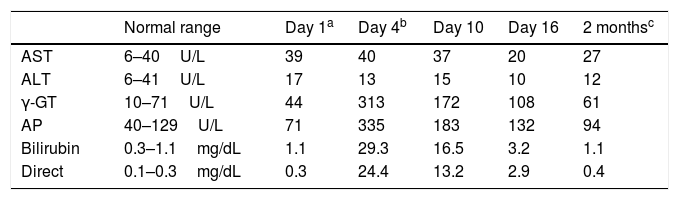

Time course of liver tests.

| Normal range | Day 1a | Day 4b | Day 10 | Day 16 | 2 monthsc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST | 6–40U/L | 39 | 40 | 37 | 20 | 27 |

| ALT | 6–41U/L | 17 | 13 | 15 | 10 | 12 |

| γ-GT | 10–71U/L | 44 | 313 | 172 | 108 | 61 |

| AP | 40–129U/L | 71 | 335 | 183 | 132 | 94 |

| Bilirubin | 0.3–1.1mg/dL | 1.1 | 29.3 | 16.5 | 3.2 | 1.1 |

| Direct | 0.1–0.3mg/dL | 0.3 | 24.4 | 13.2 | 2.9 | 0.4 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; γ-GT, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase.

PT was discontinued and imipenem/cilastatin was initiated at 500mg IV every 6h, according to the antibiogram of E. coli (sensitive to: PT, imipenem and colistin; resistant to: ciprofloxacin, ampicillin/sulbactam, ceftriaxone and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole). Symptoms gradually subsided over the subsequent days. This was paralleled by declining levels of liver enzymes and bilirubin (Table 1a). The patient refused a liver biopsy and was discharged symptom free on day 16 of hospitalization. Lymphocyte transformation test (LTT) for piperacillin was positive. Two months after discharge, the patient presented with normal liver function tests.

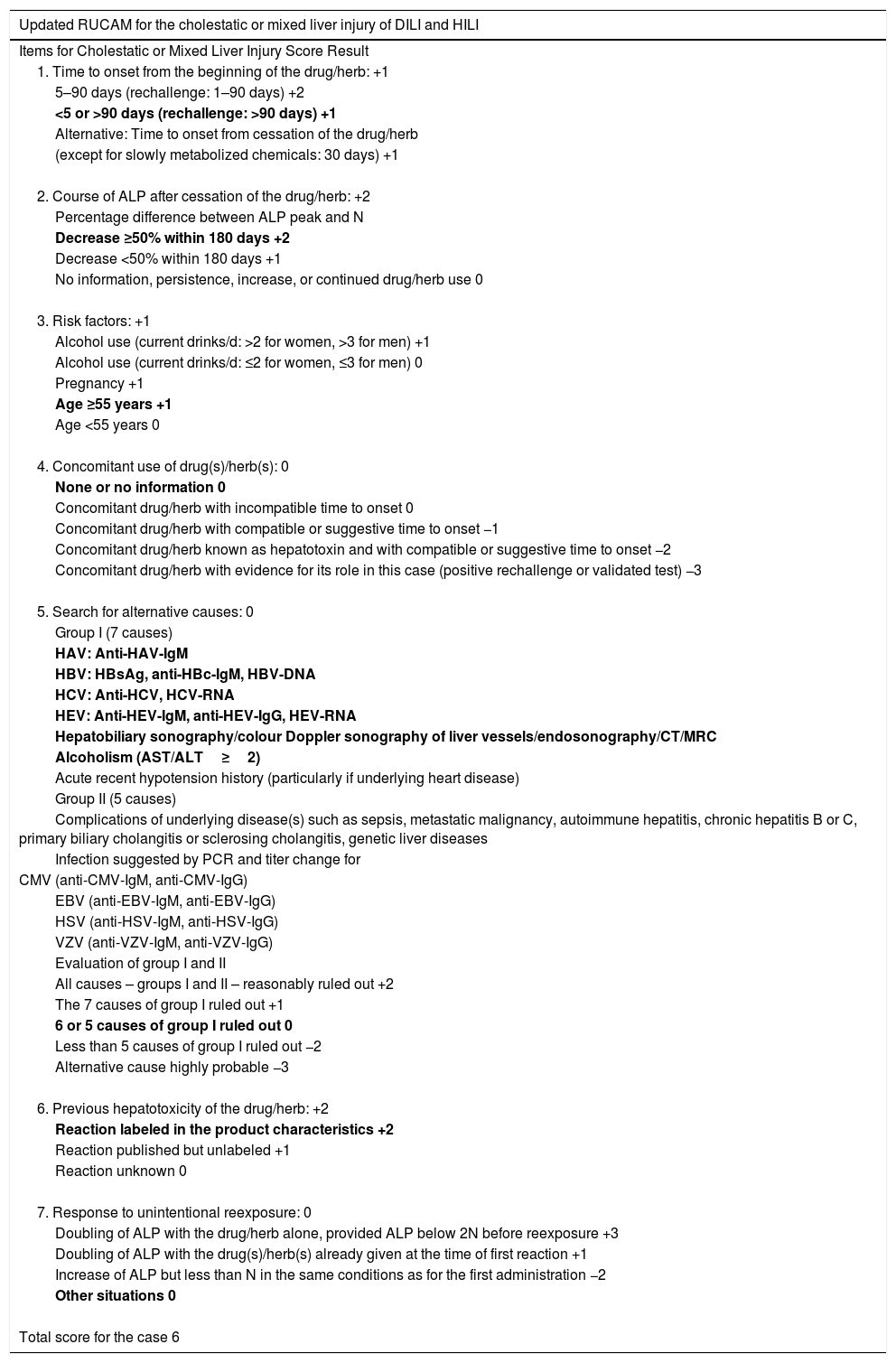

Clinical presentation, laboratory and imaging findings, lack of association between hepatic cholestasis and the other drugs administered, type of liver injury observed (cholestasis, more associated with penicillins) and response to change in treatment of this case support a diagnosis of hepatic cholestasis, probably caused by PT. This definition of probable adverse drug reaction is suggested by a score of 7 on the Naranjo probability scale.1 This association was supported by the use of hepatotoxicity-specific causality scales. We used the updated Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) scale to determine if patient had cholestatic or mixed liver injury of drug induced liver injury (DILI) or herb induced liver injury (HILI). This patient R (= alanine aminotransferase/alkaline phosphatase) value was ≤2, which expressed cholestatic liver injury. His updated RUCAM score was 6 (Table 1b) and indicated that our case was probably of a DILI.2

Evaluation of the updated Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) for the cholestatic or mixed liver injury of DILI and HILI for piperacillin/tazobactam.

| Updated RUCAM for the cholestatic or mixed liver injury of DILI and HILI |

|---|

| Items for Cholestatic or Mixed Liver Injury Score Result |

| 1. Time to onset from the beginning of the drug/herb: +1 |

| 5–90 days (rechallenge: 1–90 days) +2 |

| <5 or >90 days (rechallenge: >90 days) +1 |

| Alternative: Time to onset from cessation of the drug/herb |

| (except for slowly metabolized chemicals: 30 days) +1 |

| 2. Course of ALP after cessation of the drug/herb: +2 |

| Percentage difference between ALP peak and N |

| Decrease ≥50% within 180 days +2 |

| Decrease <50% within 180 days +1 |

| No information, persistence, increase, or continued drug/herb use 0 |

| 3. Risk factors: +1 |

| Alcohol use (current drinks/d: >2 for women, >3 for men) +1 |

| Alcohol use (current drinks/d: ≤2 for women, ≤3 for men) 0 |

| Pregnancy +1 |

| Age ≥55 years +1 |

| Age <55 years 0 |

| 4. Concomitant use of drug(s)/herb(s): 0 |

| None or no information 0 |

| Concomitant drug/herb with incompatible time to onset 0 |

| Concomitant drug/herb with compatible or suggestive time to onset −1 |

| Concomitant drug/herb known as hepatotoxin and with compatible or suggestive time to onset −2 |

| Concomitant drug/herb with evidence for its role in this case (positive rechallenge or validated test) −3 |

| 5. Search for alternative causes: 0 |

| Group I (7 causes) |

| HAV: Anti-HAV-IgM |

| HBV: HBsAg, anti-HBc-IgM, HBV-DNA |

| HCV: Anti-HCV, HCV-RNA |

| HEV: Anti-HEV-IgM, anti-HEV-IgG, HEV-RNA |

| Hepatobiliary sonography/colour Doppler sonography of liver vessels/endosonography/CT/MRC |

| Alcoholism (AST/ALT≥2) |

| Acute recent hypotension history (particularly if underlying heart disease) |

| Group II (5 causes) |

| Complications of underlying disease(s) such as sepsis, metastatic malignancy, autoimmune hepatitis, chronic hepatitis B or C, primary biliary cholangitis or sclerosing cholangitis, genetic liver diseases |

| Infection suggested by PCR and titer change for |

| CMV (anti-CMV-IgM, anti-CMV-IgG) |

| EBV (anti-EBV-IgM, anti-EBV-IgG) |

| HSV (anti-HSV-IgM, anti-HSV-IgG) |

| VZV (anti-VZV-IgM, anti-VZV-IgG) |

| Evaluation of group I and II |

| All causes – groups I and II – reasonably ruled out +2 |

| The 7 causes of group I ruled out +1 |

| 6 or 5 causes of group I ruled out 0 |

| Less than 5 causes of group I ruled out −2 |

| Alternative cause highly probable −3 |

| 6. Previous hepatotoxicity of the drug/herb: +2 |

| Reaction labeled in the product characteristics +2 |

| Reaction published but unlabeled +1 |

| Reaction unknown 0 |

| 7. Response to unintentional reexposure: 0 |

| Doubling of ALP with the drug/herb alone, provided ALP below 2N before reexposure +3 |

| Doubling of ALP with the drug(s)/herb(s) already given at the time of first reaction +1 |

| Increase of ALP but less than N in the same conditions as for the first administration −2 |

| Other situations 0 |

| Total score for the case 6 |

Words in bold represent corresponding items for this patient, and his score is shown on the right side of each heading. A total score of 6 is shown at the bottom of this table.

Concerning etiology, there is little doubt that the cholestasis observed in this patient was caused by PT, due to the previously exposed. However, sometimes sepsis and inflammatory conditions may lead to cholestasis and we must consider it as differential diagnosis. Despite this, in our case the patient started with symptoms two days before the consultation and liver tests were normal at admission.

Unfortunately the liver biopsy was not performed to support the diagnosis and rule out other diagnoses. While not always necessary, this procedure may be essential in selected cases, especially to assess the patient's prognosis. Fundamentally for what has been mentioned is that the LTT was made. This test measures the proliferation of T cells to a drug in vitro, from which one concludes to a previous in vivo reaction due to a sensitization. It is important to note that LTT was performed 14 days after the acute clinical manifestation because the sensitized lymphocytes may still reside in the affected organs and can, therefore not be obtained in the periphery.3

To our knowledge, there are in the English literature 2 prior reports of PT-induced cholestasis, none of which were cholestasis without hepatitis (pure cholestasis). Quattropani et al.4 reported that a young man developed a severe and reversible cholestatic hepatitis after short-term administration of piperacillin and imipenem/cilastatin. The biopsy revealed centrizonal bilirubinostasis, a portal infiltrate rich in eosinophils and cholangitis, compatible with an underlying immunological mechanism. Dietze et al.5 communicated a case of a woman treated with piperacillin (ten days), who developed a reversible cholestatic hepatitis. Our report is the first detailed case report in the literature of a pure PT-induced cholestasis.

FundingThe authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We thank Mariana Castro, M.D., for the English editing.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.