Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019)

Más datosCurrently, the prevalence of colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks among the top four diseases in the world. Indonesia ranks third in CRC, with poor survival rates. The high prevalence of CRC requires early diagnosis and intervention. This is expected to improve the survival rate of patients with CRC. The aim of this study was to compare the survival rate of patients based on age and pathological categories.

MethodsThis study was an observational, analytic study with a cross-sectional approach consisting of 470 patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer in our institution. Data was obtained from medical records, and univariate, bivariate, multivariate data analyses and survival analysis were performed.

ResultsMost CRCs occur in the rectal area (41.3%). Those who experienced metastasis (25.8%) were mostly liver cancer patients, mostly in stage 3 (67.2%), with a moderate differentiation rate of 82.8 percent. This study proves that there is a significant difference between survival rates for age categories where age≥50 years tends to have a lower survival rate (HR 1.6; p<0.05). Survival rate is also influenced by differences in stadium (HR; 4.6; p<0.05).

ConclusionThis study shows that the survival rate for colorectal cancer patients at our institution is mostly <5 years. Age and pathology are the deciding factors in determining survival rates. Early diagnosis and immediate therapy are important steps in reducing mortality and morbidity.

Globally, colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common types of cancer. In Western countries, it is the second leading cause of cancer mortality. The differences in survival rates observed in various clinical trials may be due to variations in patients’ characteristics and prognostic factors.1

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers in Indonesia, and the incidence is slowly increasing.2,3 According to GLOBOCAN 2018, the incidence of colorectal cancer in Indonesia was 30,017 out of 348,809 (8.6%) cases in Indonesia, with a mortality rate fifth (7.7%) among all cancer cases.4 With a median age of 71 years at diagnosis, it is often considered a disease of the elderly, even though it also exists among the young.4 The rise in incidence might, at least in part, be related to the parallel increase in average lifespan. Improved standards of living along with better healthcare can promote longer lives. Parallel advances in medicine can bring not only new treatments, but also the possibility of treating patients in more advanced stages of disease, as well as hampering co-morbidity. Patients who in earlier decades would have been considered ineligible for surgery are today successfully treated. The same development also benefits young patients as neoadjuvant regimens can advance the limits of surgical resectability and improve the chances of curative treatment.5

The risk of a CRC starts to increase after the age of 40 and then increases sharply at 50–55 years; it then doubles every subsequent decade. Nowadays, many cases of CRC are found at younger ages. Data from GLOBOCAN indicates that the incidence of CRC in the United States decreases at over 50 years of age, and at 20–49 years the incidence increases. The incidence of CRC at the age of 20–49 in 1975 was 9.3/100,000, and it increased to 13.7/100,000 in 2015, an increase of about 47.31%, while the incidence in the age group above 50 years decreased. Indonesia has a greater percentage of young CRC patients compared to other countries.6 Over the past years, several research groups have suggested numerous factors associated with the survival of CRC patients.7,8 However, the extent of tumor infiltration into the bowel wall, adjacent lymph node metastases, and distant metastasis are the major contributing factors.9,10 Prognosis for patients with colorectal cancer is much influenced by factors relating to patients’ characteristics and the tumors. In terms of age and survival of CRC sufferers, it is stated that a CRC at a very young age is worse than old age.5,11,12

In the description above, it is shown age can be a factor that contributes to the survival rate of this disease. Therefore, this study aims to describe the effect of age and tumor characteristics in predicting CRC survival rates. Knowledge of prognostic factors in our population will be the foundation for planning treatment and predicting the outcome of patients with CRC. Thus, we investigated the survival rate of CRC and its prognostic factors among patients in our institution.

MethodsThis retrospective, observational study was conducted in our institution. A total of 466 cases of CRC, recorded from 2013 to 2015, were retrospectively retrieved from the medical records regarding socio-demographic characteristics and clinical and pathological variables including grade of tumor and staging.

Patients were contacted during their follow-up visits to the hospital, and those who could not report for review at the hospital were contacted via telephone. Deaths of subjects were confirmed via contact with their relatives. Survival periods were calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of either last follow-up or death. Those lost to follow-up were excluded.

Data entry and analysis were performed using SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp., released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Statistical analyses were performed, including chi-square, t-test, and ANOVA test as indicated. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to assess survival, and the log-rank test was used to compare differences between the groups. A Cox multivariate survival analysis was performed, including stage (differentiation grade, diagnosis, and age), both overall with age as a continuous factor and by age groups. Findings with p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsThis study employed an observational, analytic design with a cross-sectional method that aims to compare survival rates with ages of patient when diagnosed with CRC. In addition, this study compares differences in other characteristics including sex, location of cancer, differentiation of cancer, and staging of cancer.

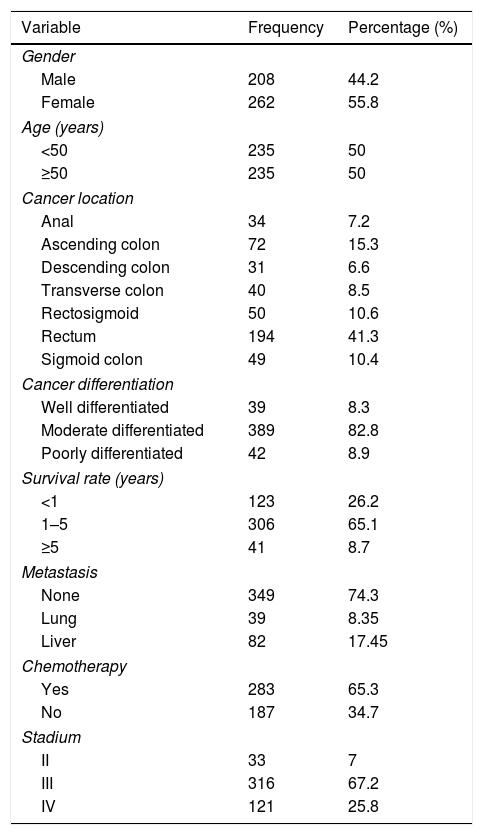

There were a total 470 samples in this study, obtained through medical record tracking in our institution. The samples consisted of 235 patients<50 years old and 235 patients≥50 years old when diagnosed with CRC. Most CRCs are located in the rectum (41.3%). Most of the patients were female (50.1%). There were 82.8% patients with moderate differentiation, and most of them were at stage III (67.2%).

Survival rate is the main point of this study, and it was mostly in the range of 1–4 years after CRC diagnosis, with a percentage of 6.1. The survival rate<1 year was 26.2%, and the ≥5-year survival rate was 8.7 percent. Distribution of patient characteristics is shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of colorectal cancer patients.

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 208 | 44.2 |

| Female | 262 | 55.8 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <50 | 235 | 50 |

| ≥50 | 235 | 50 |

| Cancer location | ||

| Anal | 34 | 7.2 |

| Ascending colon | 72 | 15.3 |

| Descending colon | 31 | 6.6 |

| Transverse colon | 40 | 8.5 |

| Rectosigmoid | 50 | 10.6 |

| Rectum | 194 | 41.3 |

| Sigmoid colon | 49 | 10.4 |

| Cancer differentiation | ||

| Well differentiated | 39 | 8.3 |

| Moderate differentiated | 389 | 82.8 |

| Poorly differentiated | 42 | 8.9 |

| Survival rate (years) | ||

| <1 | 123 | 26.2 |

| 1–5 | 306 | 65.1 |

| ≥5 | 41 | 8.7 |

| Metastasis | ||

| None | 349 | 74.3 |

| Lung | 39 | 8.35 |

| Liver | 82 | 17.45 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 283 | 65.3 |

| No | 187 | 34.7 |

| Stadium | ||

| II | 33 | 7 |

| III | 316 | 67.2 |

| IV | 121 | 25.8 |

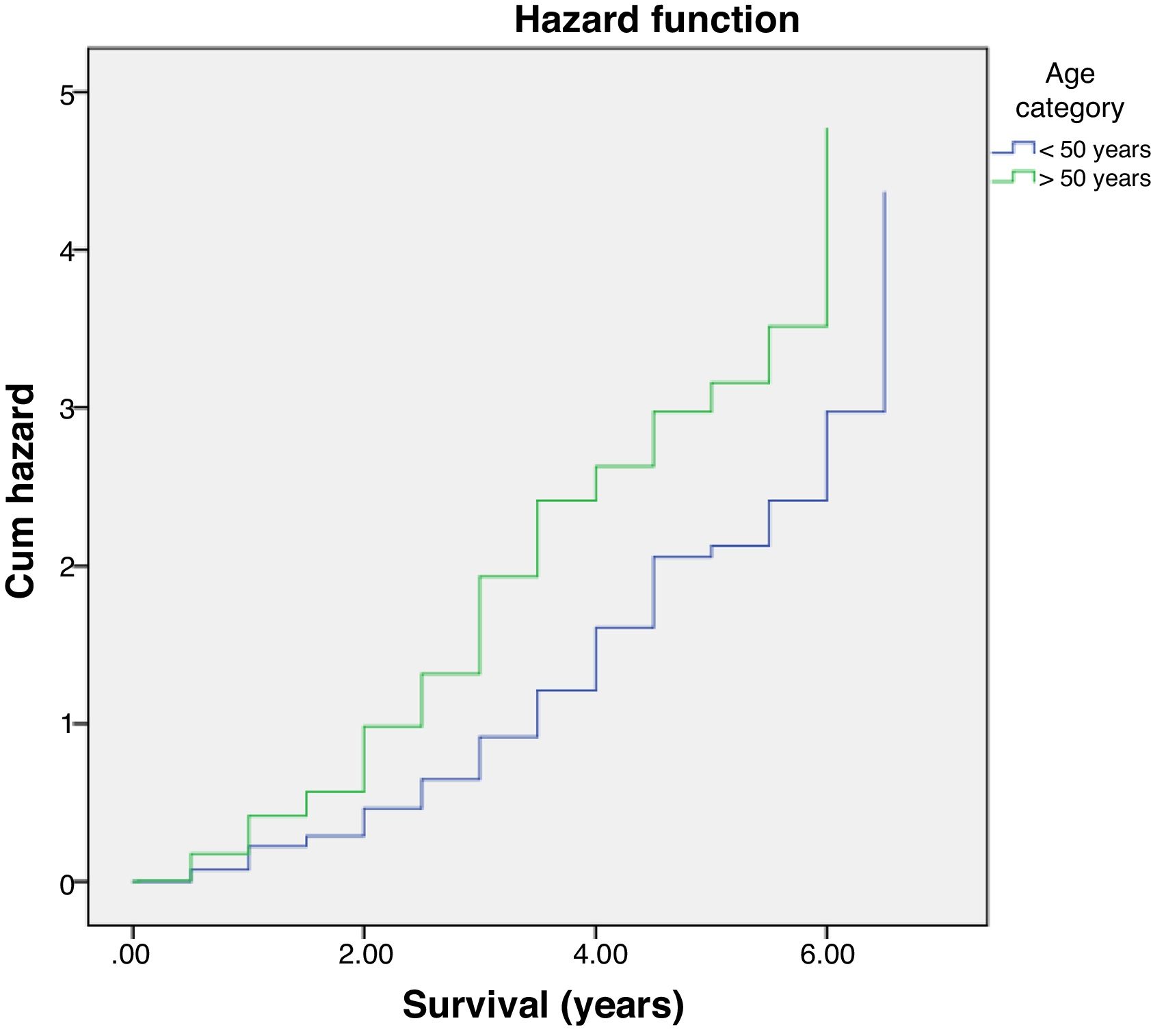

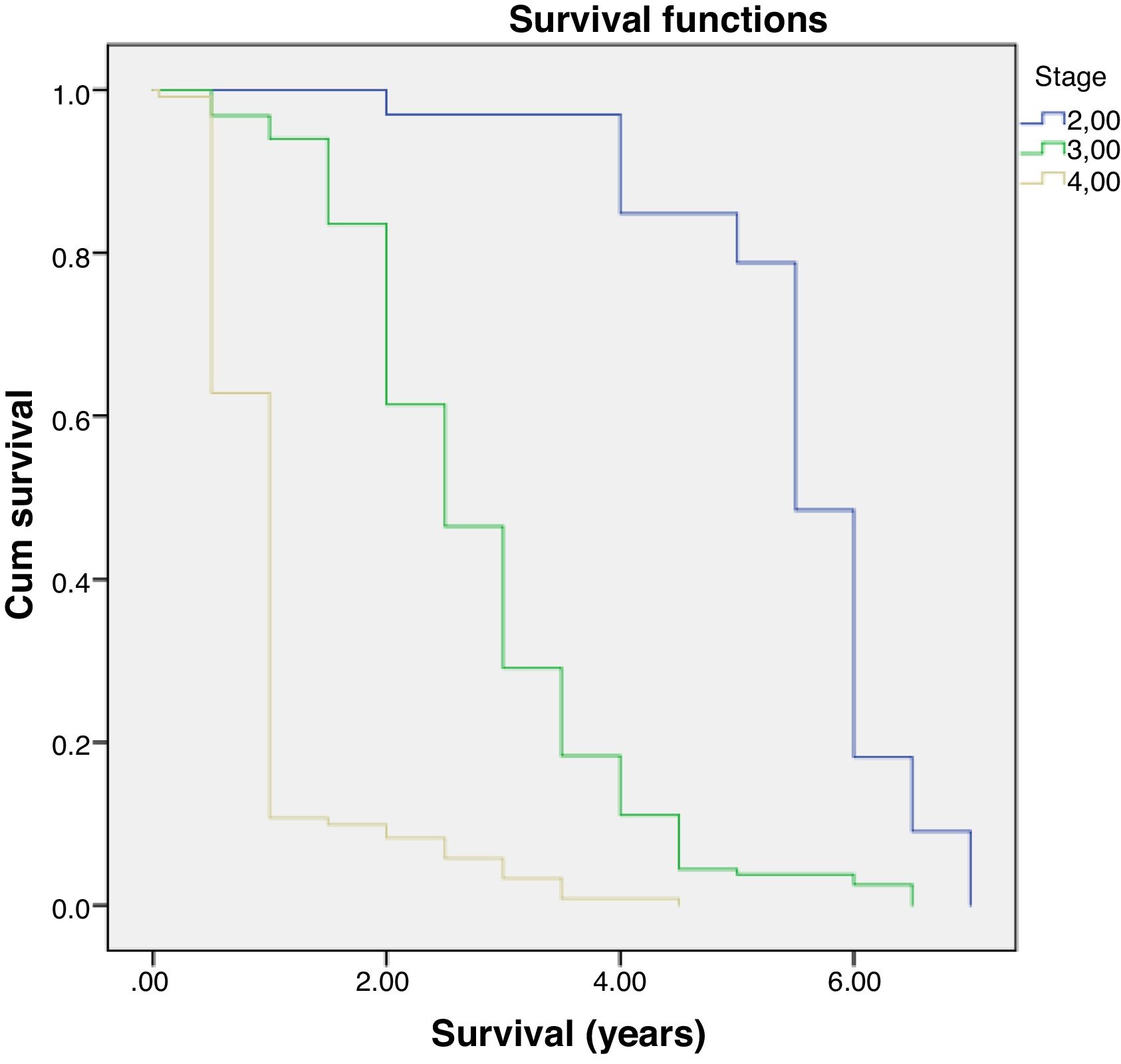

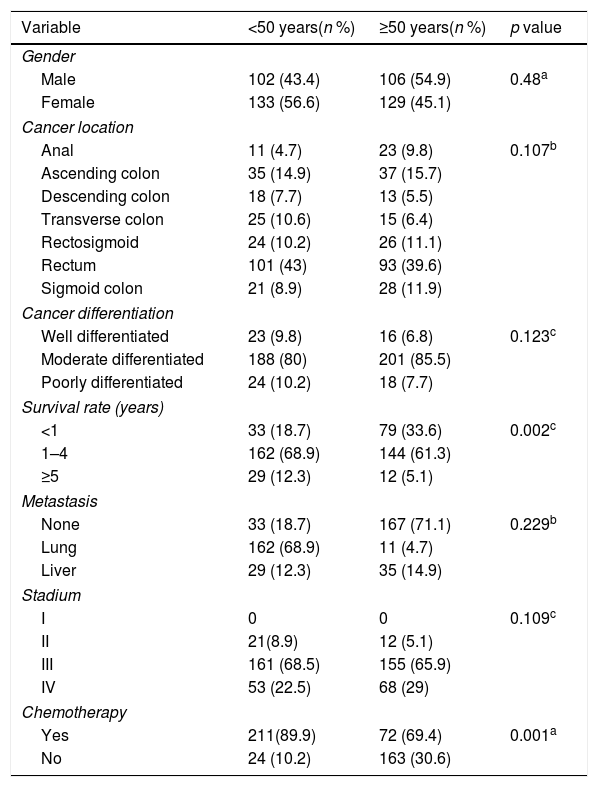

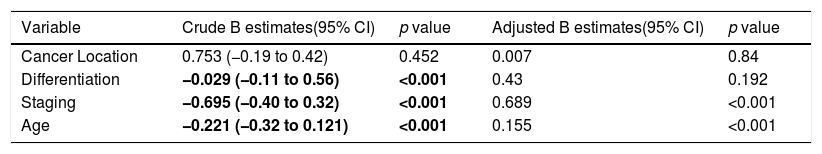

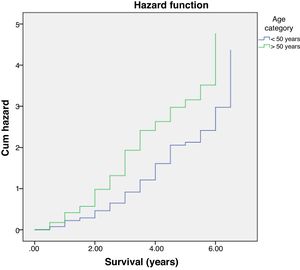

Multivariate analysis showed that age and staging are the main factors affecting the survival rate of CRC (Table 2). Differentiation grade had influence, but it did not correlate directly with CRC, as shown in Table 3. Next, analysis was carried out using the survival rate in assessing the differences in survival between the two groups. The analysis was carried out using the Kaplan–Meier curve, and results were found in line with the previous analysis. Difference in age resulted in a different outcome in the survival rate of colorectal cancer patients, which was proven to be statistically significant with p-value<0.05 (Fig. 1).

Analysis of colorectal cancer patient characteristics based on age.

| Variable | <50 years(n %) | ≥50 years(n %) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 102 (43.4) | 106 (54.9) | 0.48a |

| Female | 133 (56.6) | 129 (45.1) | |

| Cancer location | |||

| Anal | 11 (4.7) | 23 (9.8) | 0.107b |

| Ascending colon | 35 (14.9) | 37 (15.7) | |

| Descending colon | 18 (7.7) | 13 (5.5) | |

| Transverse colon | 25 (10.6) | 15 (6.4) | |

| Rectosigmoid | 24 (10.2) | 26 (11.1) | |

| Rectum | 101 (43) | 93 (39.6) | |

| Sigmoid colon | 21 (8.9) | 28 (11.9) | |

| Cancer differentiation | |||

| Well differentiated | 23 (9.8) | 16 (6.8) | 0.123c |

| Moderate differentiated | 188 (80) | 201 (85.5) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 24 (10.2) | 18 (7.7) | |

| Survival rate (years) | |||

| <1 | 33 (18.7) | 79 (33.6) | 0.002c |

| 1–4 | 162 (68.9) | 144 (61.3) | |

| ≥5 | 29 (12.3) | 12 (5.1) | |

| Metastasis | |||

| None | 33 (18.7) | 167 (71.1) | 0.229b |

| Lung | 162 (68.9) | 11 (4.7) | |

| Liver | 29 (12.3) | 35 (14.9) | |

| Stadium | |||

| I | 0 | 0 | 0.109c |

| II | 21(8.9) | 12 (5.1) | |

| III | 161 (68.5) | 155 (65.9) | |

| IV | 53 (22.5) | 68 (29) | |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Yes | 211(89.9) | 72 (69.4) | 0.001a |

| No | 24 (10.2) | 163 (30.6) | |

Survival rate factors in colorectal cancer patients.

| Variable | Crude B estimates(95% CI) | p value | Adjusted B estimates(95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Location | 0.753 (−0.19 to 0.42) | 0.452 | 0.007 | 0.84 |

| Differentiation | −0.029 (−0.11 to 0.56) | <0.001 | 0.43 | 0.192 |

| Staging | −0.695 (−0.40 to 0.32) | <0.001 | 0.689 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.221 (−0.32 to 0.121) | <0.001 | 0.155 | <0.001 |

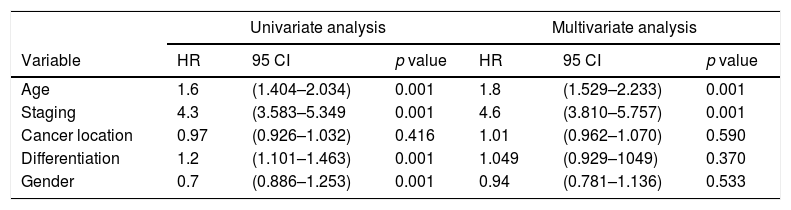

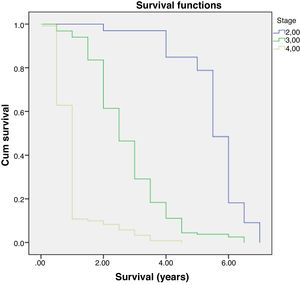

Further analysis was performed to determine hazard ratio, as shown in Fig. 2. Based on Cox regression, we found that at age≥50 years, patients had a risk about 1.6 times greater than people aged<50 years. Furthermore, this study also showed that stages of cancer affected survival rates of patients with CRC. Based on a Kaplan–Meier curve analysis, it was shown that staging is an important factor in determining the survival of colorectal cancer patients. The higher the CRC stage, the smaller the survival rate by a significant degree (p<0.05). This was associated with hazard analysis of stadiums based on survival time. The higher the stage of the cancer, the higher the hazard. This is evidenced by a hazard ratio of 4.3 times for each stadium increase (Table 4).

Association of survival rates of patients with age and stage of CRC.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95 CI | p value | HR | 95 CI | p value |

| Age | 1.6 | (1.404–2.034) | 0.001 | 1.8 | (1.529–2.233) | 0.001 |

| Staging | 4.3 | (3.583–5.349 | 0.001 | 4.6 | (3.810–5.757) | 0.001 |

| Cancer location | 0.97 | (0.926–1.032) | 0.416 | 1.01 | (0.962–1.070) | 0.590 |

| Differentiation | 1.2 | (1.101–1.463) | 0.001 | 1.049 | (0.929–1049) | 0.370 |

| Gender | 0.7 | (0.886–1.253) | 0.001 | 0.94 | (0.781–1.136) | 0.533 |

The concept of age is connected to the passage of time and influenced by social and cultural factors. Aging itself has, somewhat cynically, been defined as an accumulation of diverse adverse changes that gradually increase the risk of death. Age in years is certainly a continuous variable, whilst the interpretations rapidly become relative in their nature.13 An example is one of several definitions of being old: years of age exceeding the average. The average life span has increased with improvements not only in healthcare but also in general living conditions, including nutrition. Thus, interpretations of “old” and “elderly” can vary with time and country. This becomes clear when reading publications on the subject where the limit for being classified as “old” is highly variable and has been pushed out further.12 The fact is that the increasing survival rate is not only affected by technology and the science of medicine, but also by the general living conditions of society including nutrition, socio-cultural factors, and access to health services.14–16

A significant relationship found in this study was that the CRC survival rate is highly related to age. The study found that there was a strong correlation between the age of patients diagnosed with CRC and their survival rates. In this study, it is shown that older patients have lower life expectancies compared to younger patients. Ghazali et al. showed similar results in their study.17 Other studies showed consistent results where older patients had higher postoperative mortality. This is related to emergency presentation and operating procedures as well as to increased risk due to degenerative processes that can be seen from cardiovascular and postoperative complications that contribute to patients’ survival rates.18–20

Chemotherapy as a treatment modality was significantly related to improved survival. Most patients with stage III disease are administered chemotherapy after surgery. Such treatment, mostly classified as “adjuvant,” helps to improve disease outcome by destroying microscopic cancer cells that could accumulate and develop into larger tumors. This combined therapy has been proven to be effective in enhancing survival by 15–20%.21–23 Another treatment difference is a lower inclusion rate of older patients into chemotherapy regimens of both adjuvant and palliative settings. One reason for this might be that age can affect the risk benefit equation when considering eligibility for and use of chemotherapy.24,25 Still, there is some evidence that elderly patients can tolerate chemotherapy treatments and can receive possible benefit from them, although there is a lack of randomized clinical trials on this group. Age-related differences in demography and treatment may thus have an effect on, or be a possible explanation behind, gender-related issues of treatment and differences in survival. Because of these considerations, the chemotherapy regimen is not given aggressively in the older age groups.5,26

Several studies contradicted this study. Zhang et al. showed that age did not have a significant role in determining the survival rate of colorectal cancer patients. They said that staging and metastatic factors, as well as the differentiation of CRC, have major roles in determining the survival rate of these patients.27–29

Besides the age factor, it is known that the survival rate of colorectal cancer is influenced by clinical differences and pathology factors of the tumors themselves. Some literature states that location, differentiation, and staging play important roles in prognostic markers of colorectal cancer patients. Another study showed that mortality was higher in the advanced stage; this was also associated with poor differentiation of CRC.29,30 Karimi et al. showed that cancer with regional and distant metastasis has a worse survival rate than localized cancer.31 This study also provides a similar picture, with significant results on cancer metastasis and differentiation as factors that influence the survival rate of colorectal cancer patients.

In this study, we analyzed the relationship of CRC location to survival rate: both groups demonstrated the same pattern of images to the location of the cancer. Also, this study did not find a significant association between the location of the cancer and survival rate. What is different is that the study by Bauer et al. shows that there are different characteristics of tumors originating in the left and right sides of patients. In this study, it was found that tumors originating in the right side had more harmful characteristics, resulting in higher mortality rates.18,32

In this present study, stage of tumor was associated with survival rate (Table 4). This is consistent with several studies which have demonstrated that advanced tumor stage is a prognostic factor associated with poor survival in patients with CRC. A Cox proportional hazard model in this current study revealed that distant metastasis was significantly associated with poor survival. This finding is supported by many other studies which also identified distance metastasis as a significant factor for poor survival.28,33

The current authors believe that this study demonstrates some support for a hypothesis of more aggressive tumor characteristics among younger patients who can tolerate treatment and disease better and for longer. The survival data may be of importance for use in choosing evaluation parameters, particularly in an aging population. The current authors also concur with findings of previous studies that cancer surgery is feasible in the oldest patient group.5,33

A decreasing age-related survival rate is supported by a hazard ratio increasing with age. In this study, it is shown that the >50 age group has a hazard ratio 1.6 times higher compared to patients who are younger, and this is the same with increasing stage, with a hazard ratio of 4.3 times. This is comparable to research conducted by Agyemang-Yeboah et al. which states that HR for the average age group has a hazard ratio >1, and the hazard ratio for each stage is 3.4. The increasing hazard ratio is a reflection of a decrease in survival rate, and other factors are related to one another.33

Eventually, it was discovered that the survival rate of CRC is composed by a combination of various factors. Moghimi shows that differences in the method of initial diagnosis, history of alcohol use, initial treatment methods, and history of metastasis are factors that can predict CRC mortality, but economic status, education, and other comorbid factors have not been included in the analysis.18

ConclusionsIn this study, it is shown that the age of patients diagnosed with CRC affects survival rate. This is supported by the fact that there are significant differences in terms of the aggressiveness of treatment with a chemotherapy regimen as a result of degenerative processes that harm patients. It is also shown in this study that patient age when diagnosed with CRC provides a differing picture in terms of survival rate. This is supported by the fact that there are significant differences in terms of the aggressiveness of treatment using a chemotherapy regimen as a result of degenerative processes that become harmful with increasing age of patients. A therapeutic regimen is given by observing the principle of the benefits of therapy.

Authors’ contributionsConceived and designed the study: ABD, MP, MIK, ES, and SM. Data collection and analysis: ABD, and MF. Wrote manuscript: ABD, MP, MIK, SM, ES, and MF. Tables and figures creation: ABD ES, and MF. Supervision: WS, IL, JAW, JH, MIK and SM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approvalThe ethical approval of this study was granted from Ethics Commission our institution number: 243/UN4.6.4.5.31/PP36/2020.

ConsentWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this research.

FundingNo funding or sponsorship.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the Technology Enhanced Medical Education International Conference (THEME 2019). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.