Snakebites are one of the most important health issues globally that cause morbidity, discomfort, and even death. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical features of snakebite in patients referred to Razi Hospital in Ghaemshahr city.

MethodsIn this descriptive, cross-sectional study, 325 snakebite patients admitted to Razi Hospital in Qaemshahr city between the years 2014 and 2019 were studied. All information was extracted from patients' medical records. SPSS software version 25 was used to analyze the data.

ResultsPatients ranged in age from 9 to 71 years with a mean of 36.6±10.7 years. 238 cases (73.2%) were male and 87 cases (26.8%) were female. The highest frequency of bites with 162 cases (49.8%) was related to the lower extremities and summer with 122 cases (37.5%) had the highest frequency of bites. The highest frequency of local symptoms was related to bruising (17.8%), erythema (16.9%), and pain (15.7%), and the highest frequency of systemic symptoms were related to weakness (24%), and sweating (14.2%). For 88.2% of cases, antivenom was used. 33.8% of the patients received antibiotics, mostly ciprofloxacin+clindamycin.

ConclusionThe results obtained in this study showed that common local complications in patients included bruising, erythema, and edema and systemic complications such as weakness, subcutaneous bleeding, and sweating. Antivenom was used for most of the cases and no deaths were reported. Also, unscientific actions such as incision and suction are still performed in cases that require more awareness and training.

Las mordeduras de serpientes son uno de los problemas de salud más importantes a nivel mundial que causan morbilidad, malestar e incluso la muerte. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo evaluar las características clínicas de la mordedura de serpiente en pacientes remitidos al Hospital Razi en la ciudad de Ghaemshahr.

MétodosEn este estudio descriptivo transversal, se estudiaron 325 pacientes con mordedura de serpiente ingresados en el Hospital Razi en la ciudad de Qaemshahr entre los años 2014 a 2019. Toda la información se extrajo de las historias clínicas de los pacientes. Se utilizó el software SPSS versión 25 para analizar los datos.

ResultadosLos pacientes tenían edades comprendidas entre 9 y 71 años con una media de 36,6±10,7 años. 238 casos (73,2%) eran hombres y 87 casos (26,8%) eran mujeres. La mayor frecuencia de mordeduras con 162 casos (49,8%) estuvo relacionada con las extremidades inferiores y verano con 122 casos (37,5%) tuvo la mayor frecuencia de mordeduras. La mayor frecuencia de síntomas locales se relacionó con hematomas (17,8%), eritema (16,9%) y dolor (15,7%), y la mayor frecuencia de síntomas sistémicos se relacionó con debilidad (24%) y sudoración (14,2%). En el 88,2% de los casos se utilizó antiveneno. El 33,8% de los pacientes recibieron antibióticos, en su mayoría ciprofloxacino + clindamicina.

ConclusiónLos resultados obtenidos en este estudio mostraron que las complicaciones locales comunes en los pacientes incluyeron hematomas, eritemas y edemas y complicaciones sistémicas como debilidad, sangrado subcutáneo y sudoración. Se usó antiveneno en la mayoría de los casos y no se informaron muertes. Además, todavía se realizan acciones no científicas como la incisión y la succión en casos que requieren más conciencia y capacitación.

Snakebite is one of the most important medical emergencies and even may lead to death.1 About, 10% out of 3500 snake species around the world are determined to be perilous to humans.1 The number of snakebites throughout the world ranges from 1.2 to 5.5 million cases per annum, and the number of deaths as a result of snakebites envenomation were between 20 000 and 94 000 yearly.1,2 In Iran, the rate of snakebite is about 4500–6500 cases which result in 3–9 deaths annually.3,4 The Colubridae, Viperidae, Elapidae, and Hydrophidae, are the most common venomous snakes in Iran.5 Echis carinatus sochureki, from Viperidae family, are amongst the most hazardous snakes in Iran.6

The clinical symptoms as a result of snakebite are variable and it depends on different factors including snake’s species, amount of venom, age as well as physical conditions of bitted individuals.7 After being bitten by venomous snakes, various medical emergencies may happen such as bleeding disorders, severe paralysis that may be accompanied by shortness of breath that may lead to suffocation, irreversible renal failure, and severe necrosis in local tissue that may need amputation.8 In Iran, there is a high rate of snake bites every year, which causes a large number of patients to refer to medical centers.9,10 On the other hand, snake bites can cause the immediate death of the patient, thus, accurate and correct familiarity with this issue and initial treatment methods is necessary.11

Mazandaran province and Qaemshahr city are among the areas in Iran where agriculture is common and on the other hand, is a suitable habitat for many species of venomous and non-venomous snakes. In addition, the Razi Educational and Medical Center of Qaemshahr receives snakebite patients from surrounding cities. Understanding the epidemiology of snakebite and its clinical and laboratory symptoms in this region provides very useful information to the health system that can be used to effectively manage the prevention and treatment of complications and death from snakebite. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the clinical features of snakebite in patients referred to Razi Hospital in Qaemshahr during the years 2014–2019.

Materials and methodsThis is a descriptive cross-sectional study. All snakebite patients referred to and hospitalized in Razi Hospital of Qaemshahr city during the years 2014–2019 were evaluated. A total of 325 patients in the years 2014 (38 cases), 2015 (46 cases), 2016 (70 cases), 2017 (41 cases), 2018 (48 cases), and 2019 (82 cases) were bitten by snakes.

In this study, first, the necessary permits to access patients' files were obtained from the medical school, then, the project manager explained the purpose of the study to the officials of the medical training center. Then, among 398 files related to bites, 325 files of patients referred to Razi Hospital in Qaemshahr who had a diagnosis of snakebite were examined. The exclusion criteria were incomplete medical records of patients, cases related to other bites such as scorpion bites, and trauma, or other problems accompanied by snakebite. Using the designed checklist, demographic information and data related to patients' clinical and laboratory symptoms at the time of hospitalization were extracted. The variables evaluated in this checklist include age, sex, bite site, bitten side of the limb (left/right), local symptoms, systemic symptoms, bite site cellulite, results of laboratory tests, and the number of antivenom and antibiotics used for the patient and finally the outcome of patients (death/discharge).

In cases where patients exhibited severe symptoms, they were administered polyvalent antivenom. In other conditions, patients received pentavalent antivenom.

During hospitalization, the total number of vials of antivenom administered to each patient was recorded as the number of antivenoms. The clinical presentation of the patient played a crucial role in determining the need for additional doses of antivenom. The decision regarding the amount of antivenom required was based on the assessment of snakebite severity, which was evaluated by considering the extent of local and systemic symptoms, as well as laboratory findings including coagulation abnormalities. Therefore, the number of antivenoms administered to each patient was determined by their clinical presentation and the severity of their snakebite.

During the study, symptoms were documented at the time of admission and at regular intervals throughout the patient's hospitalization. Symptoms were documented every 6 h for the first 24 h and then every 12 h until discharge. The attending physician or nursing staff was responsible for documenting the symptoms, which were then recorded in the patient's medical record.

Statistical analysisData analysis was performed using SPSS software version 25. For statistical analysis of this study, in the descriptive statistics section, central indices (mean) and dispersion index (standard deviation) for quantitative variables as well as frequency and percentage for qualitative data were used.

Ethical considerationThe study is approved by the ethics committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (IR.MAZUMS.REC.1399.405). The study was performed according to the Helsinki Principals of Ethics. All participants signed written informed consent.

ResultA study of 325 patients with snake bites showed that the patients ranged in age from 9 to 71 years with a mean and standard deviation of 36.6±10.7 years. Also, the highest frequency of patients is related to the age group of 21–45 years with 234 cases (72%). Of all patients, 73.2% were male and 26.8% were female. The job of 82.5% of the cases was agriculturist, and 7.4% were stock breeder.

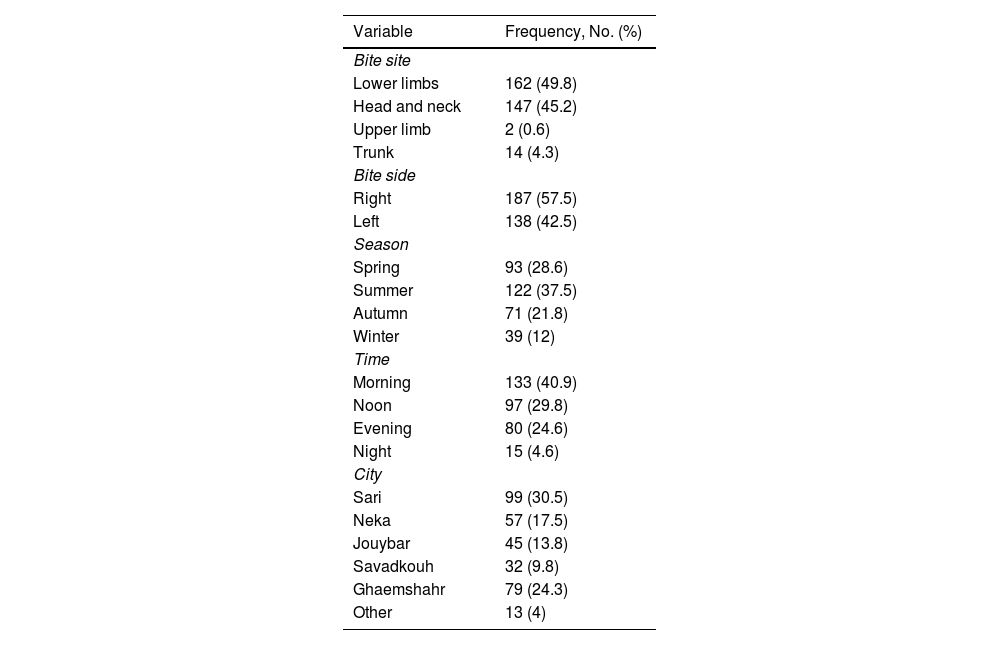

The highest frequency of bite site was related to the lower limb (49.8%) and then to the upper limb (45.2%). The lowest frequency was related to the head and neck (0.6%). The highest frequency of bite sides was related to the right side (57.5%). In addition, summer with 122 cases (37.5%) has the highest frequency of bites, followed by spring (28.6%). The highest frequency of bite time was in the morning (40.9%), followed by noon (29.8%) and evening (24.6%). The patients were mostly from Sari city (30.5%) and after that from Qaemshahr city (24.3%) (Table 1).

Frequency of site, side, season, time, and city of snakebite in the studied patient.

| Variable | Frequency, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Bite site | |

| Lower limbs | 162 (49.8) |

| Head and neck | 147 (45.2) |

| Upper limb | 2 (0.6) |

| Trunk | 14 (4.3) |

| Bite side | |

| Right | 187 (57.5) |

| Left | 138 (42.5) |

| Season | |

| Spring | 93 (28.6) |

| Summer | 122 (37.5) |

| Autumn | 71 (21.8) |

| Winter | 39 (12) |

| Time | |

| Morning | 133 (40.9) |

| Noon | 97 (29.8) |

| Evening | 80 (24.6) |

| Night | 15 (4.6) |

| City | |

| Sari | 99 (30.5) |

| Neka | 57 (17.5) |

| Jouybar | 45 (13.8) |

| Savadkouh | 32 (9.8) |

| Ghaemshahr | 79 (24.3) |

| Other | 13 (4) |

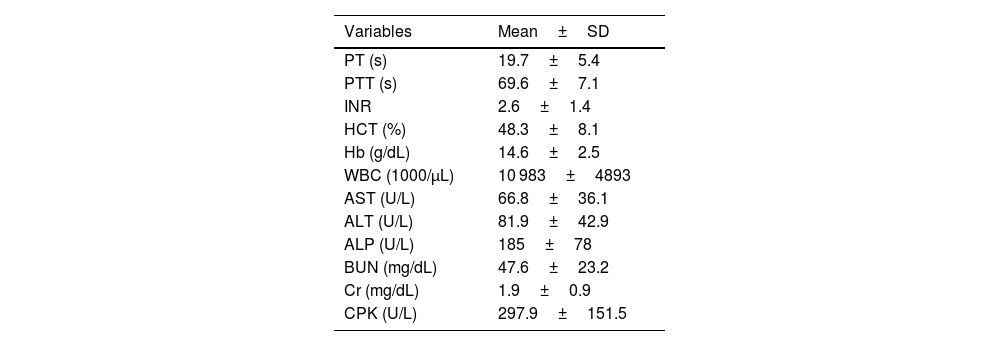

The study of patients' paraclinical variables is shown in Table 2. The mean INR, hemoglobin, and hematocrit of patients were 2.6±1.4, 14.6±2.5, and 48.3±8.1. In addition, the mean WBC of patients was 10 983±4893. Also, in the study of renal function, BUN had a mean and standard deviation of 47.6±23.2, and creatinine was 1.9±0.9.

Results of patients' paraclinical variables.

| Variables | Mean±SD |

|---|---|

| PT (s) | 19.7±5.4 |

| PTT (s) | 69.6±7.1 |

| INR | 2.6±1.4 |

| HCT (%) | 48.3±8.1 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 14.6±2.5 |

| WBC (1000/μL) | 10 983±4893 |

| AST (U/L) | 66.8±36.1 |

| ALT (U/L) | 81.9±42.9 |

| ALP (U/L) | 185±78 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 47.6±23.2 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 1.9±0.9 |

| CPK (U/L) | 297.9±151.5 |

PT: prothrombin time; PTT: Partial thromboplastin time: INR: international normalized ratio; HCT: Hematocrit; Hb: hemoglobin; AST: aspartate transaminase; ALT: alanine transaminase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; Cr: creatinine; CPK: creatine phosphokinase.

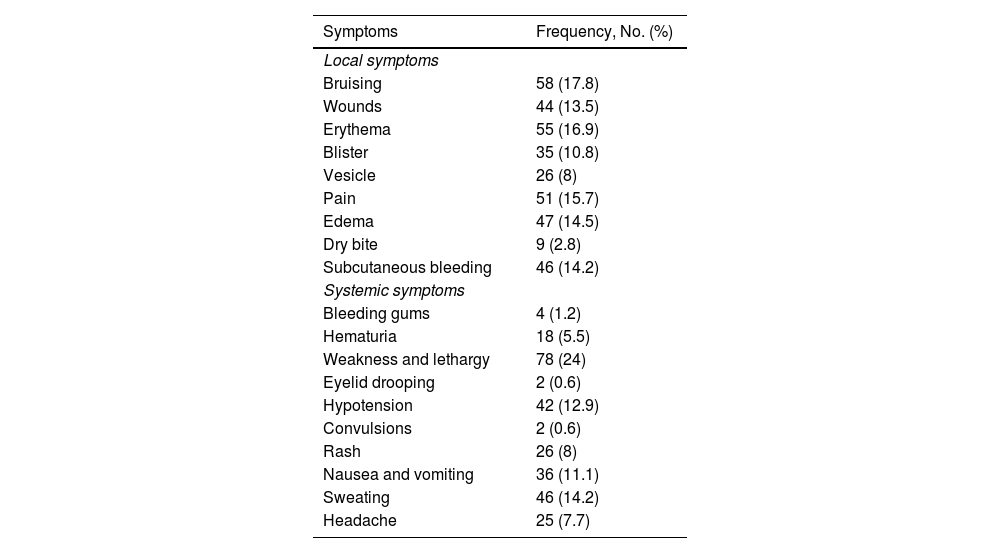

Evaluation of the frequency of local and systemic symptoms in the patients showed that the highest frequency of local symptoms was related to bruising (17.8%), followed by erythema (16.9%), pain (15.7%), edema (14.5%), subcutaneous bleeding (14.2%), and blisters (10.8%). In systemic symptoms, the highest frequency was related to weakness and lethargy (24%) followed by sweating (14.2%), hypertension (12.9%), and nausea and vomiting (11.1%) (Table 3).

Frequency of local and systemic symptoms in the studied patients.

| Symptoms | Frequency, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Local symptoms | |

| Bruising | 58 (17.8) |

| Wounds | 44 (13.5) |

| Erythema | 55 (16.9) |

| Blister | 35 (10.8) |

| Vesicle | 26 (8) |

| Pain | 51 (15.7) |

| Edema | 47 (14.5) |

| Dry bite | 9 (2.8) |

| Subcutaneous bleeding | 46 (14.2) |

| Systemic symptoms | |

| Bleeding gums | 4 (1.2) |

| Hematuria | 18 (5.5) |

| Weakness and lethargy | 78 (24) |

| Eyelid drooping | 2 (0.6) |

| Hypotension | 42 (12.9) |

| Convulsions | 2 (0.6) |

| Rash | 26 (8) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 36 (11.1) |

| Sweating | 46 (14.2) |

| Headache | 25 (7.7) |

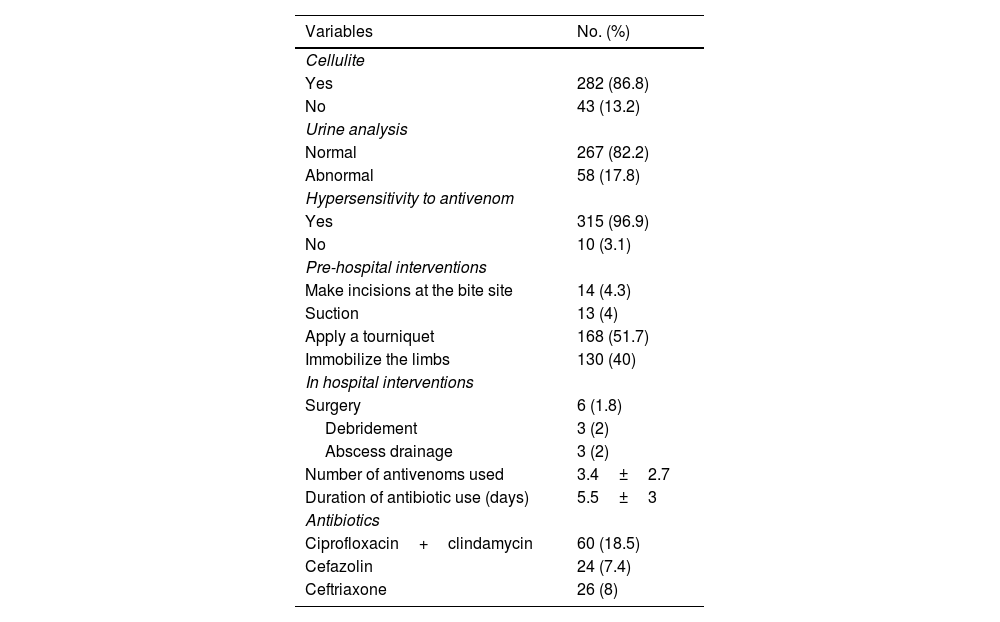

13.2% of patients had cellulite. Urine analysis was abnormal (Any urine test result that falls outside of the normal range for at least one of the parameters including; pH, protein, glucose, ketones, blood, leukocytes, nitrites, or bilirubin) in 17.8% of cases and 3.1% of cases showed hypersensitivity to antivenom (Any adverse reaction to antivenom that occurred within 24 h of administration included any of the following symptoms: rash, itching, hives, swelling, shortness of breath, wheezing, chest tightness, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or hypotension) (Table 4).

Frequency of pre-hospital and hospital interventions in snake bite patients and frequency of use of antivenom and antibiotics in patients.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Cellulite | |

| Yes | 282 (86.8) |

| No | 43 (13.2) |

| Urine analysis | |

| Normal | 267 (82.2) |

| Abnormal | 58 (17.8) |

| Hypersensitivity to antivenom | |

| Yes | 315 (96.9) |

| No | 10 (3.1) |

| Pre-hospital interventions | |

| Make incisions at the bite site | 14 (4.3) |

| Suction | 13 (4) |

| Apply a tourniquet | 168 (51.7) |

| Immobilize the limbs | 130 (40) |

| In hospital interventions | |

| Surgery | 6 (1.8) |

| Debridement | 3 (2) |

| Abscess drainage | 3 (2) |

| Number of antivenoms used | 3.4±2.7 |

| Duration of antibiotic use (days) | 5.5±3 |

| Antibiotics | |

| Ciprofloxacin+clindamycin | 60 (18.5) |

| Cefazolin | 24 (7.4) |

| Ceftriaxone | 26 (8) |

With regard to the pre-hospital intervention, the highest frequency (51.7%) was related to applying a tourniquet, followed by immobility (40%). In-hospital procedures, surgery, were performed for 6 cases (1.8%) (Table 4).

For 88.2% of hospitalized cases, antivenom was used. The number of used antivenoms was 3.4±2.7 and the duration of antibiotic use was 5.5±3 days. The study of the frequency of antibiotic use in the studied patients showed that in 33.8% of the patients, antibiotics were used, and the most used antibiotics with 60 cases (18.5%) were related to ciprofloxacin+clindamycin (Table 4).

No deaths were reported in the patients and 229 cases (70.5%) had a complete recovery and 96 cases (29.5%) had partial recovery.

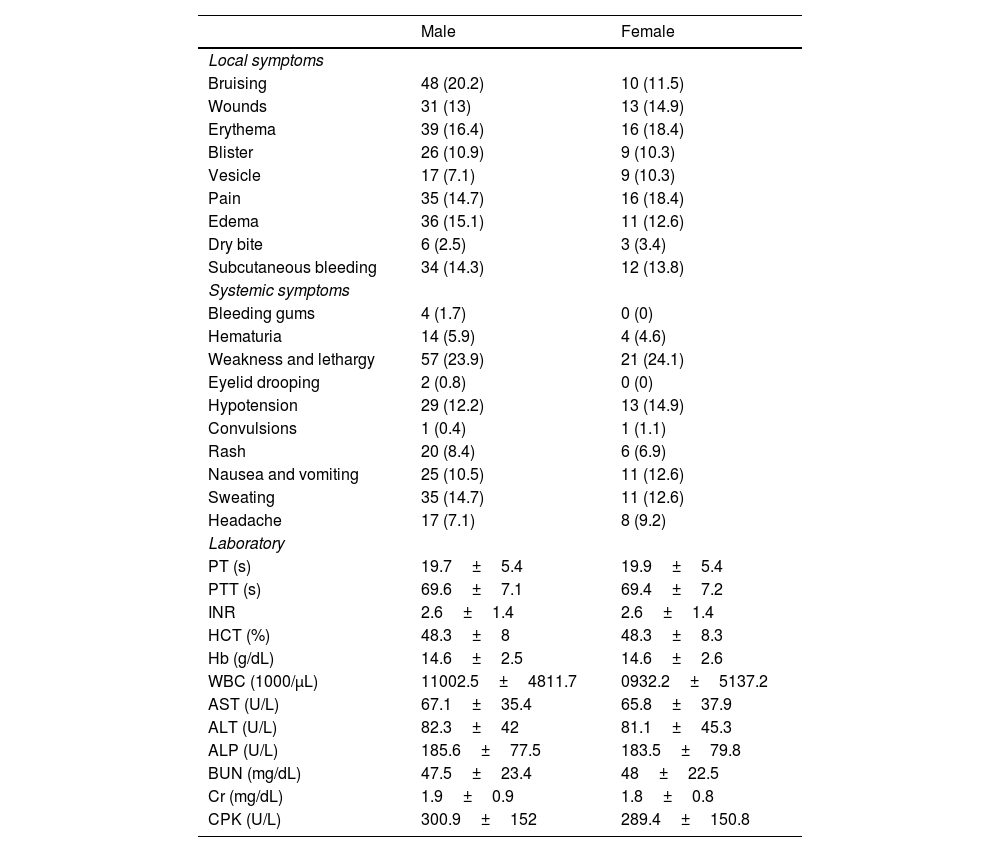

The frequency of local and systemic symptoms of patients based on gender is demonstrated in Table 5.

Frequency of local, systemic, and laboratory effects of snakebite by sex.

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Local symptoms | ||

| Bruising | 48 (20.2) | 10 (11.5) |

| Wounds | 31 (13) | 13 (14.9) |

| Erythema | 39 (16.4) | 16 (18.4) |

| Blister | 26 (10.9) | 9 (10.3) |

| Vesicle | 17 (7.1) | 9 (10.3) |

| Pain | 35 (14.7) | 16 (18.4) |

| Edema | 36 (15.1) | 11 (12.6) |

| Dry bite | 6 (2.5) | 3 (3.4) |

| Subcutaneous bleeding | 34 (14.3) | 12 (13.8) |

| Systemic symptoms | ||

| Bleeding gums | 4 (1.7) | 0 (0) |

| Hematuria | 14 (5.9) | 4 (4.6) |

| Weakness and lethargy | 57 (23.9) | 21 (24.1) |

| Eyelid drooping | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) |

| Hypotension | 29 (12.2) | 13 (14.9) |

| Convulsions | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.1) |

| Rash | 20 (8.4) | 6 (6.9) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 25 (10.5) | 11 (12.6) |

| Sweating | 35 (14.7) | 11 (12.6) |

| Headache | 17 (7.1) | 8 (9.2) |

| Laboratory | ||

| PT (s) | 19.7±5.4 | 19.9±5.4 |

| PTT (s) | 69.6±7.1 | 69.4±7.2 |

| INR | 2.6±1.4 | 2.6±1.4 |

| HCT (%) | 48.3±8 | 48.3±8.3 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 14.6±2.5 | 14.6±2.6 |

| WBC (1000/μL) | 11002.5±4811.7 | 0932.2±5137.2 |

| AST (U/L) | 67.1±35.4 | 65.8±37.9 |

| ALT (U/L) | 82.3±42 | 81.1±45.3 |

| ALP (U/L) | 185.6±77.5 | 183.5±79.8 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 47.5±23.4 | 48±22.5 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 1.9±0.9 | 1.8±0.8 |

| CPK (U/L) | 300.9±152 | 289.4±150.8 |

PT: prothrombin time; PTT: partial thromboplastin time: INR: international normalized ratio; HCT: hematocrit; Hb: hemoglobin; AST: aspartate transaminase; ALT: alanine transaminase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; Cr: creatinine; CPK: creatine phosphokinase.

The frequency of local and systemic symptoms of patients by age group is shown in Table 6.

Frequency of local and systemic symptoms of patients based on age groups.

| Less than 20 | 21–45 years | 46–60 years | Over 60 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local symptoms | ||||

| Bruising | 1 (7.7) | 39 (16.7) | 18 (23.7) | 0 (0) |

| Wounds | 1 (7.7) | 33 (14.1) | 9 (11.8) | 1 (50) |

| Erythema | 3 (23.1) | 38 (16.2) | 13 (17.1) | 1 (50) |

| Bliser | 0 (0) | 26 (11.1) | 9 (11.8) | 0 (0) |

| Vesicle | 0 (0) | 22 (9.4) | 4 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Pain | 3 (23.1) | 41 (17.5) | 7 (9.2) | 0 (0) |

| Edema | 4 (30.8) | 28 (12) | 15 (19.7) | 0 (0) |

| Dry bite | 1 (7.7) | 7 (3) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Subcutaneous bleeding | 2 (15.4) | 34 (14.5) | 9 (11.8) | 1 (50) |

| Systemic symptoms | ||||

| Bleeding gums | 0 (0) | 3 (1.3) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Hematuria | 1 (7.7) | 11 (4.7) | 6 (7.9) | 0 (0) |

| Weakness and lethargy | 3 (23.1) | 52 (22.2) | 22 (28.9) | 1 (50) |

| Eyelid drooping | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Hypotension | 3 (23.1) | 28 (12) | 11 (14.5) | 0 (0) |

| Convulsions | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) |

| Rash | 1 (7.7) | 21 (9) | 4 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 3 (23.1) | 28 (12) | 5 (6.6) | 0 (0) |

| Sweating | 0 (0) | 34 (14.5) | 12 (15.8) | 0 (0) |

| Headache | 0 (0) | 21 (9) | 4 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Laboratory | ||||

| PT (s) | 21.2±5.5 | 20±5.4 | 18.9±5.4 | 13.5±3.5 |

| PTT (s) | 71.4±8.8 | 69.3±6.9 | 70.1±7.4 | 72.5±6.4 |

| INR | 2.9±1.4 | 2.6±1.4 | 2.4±1.5 | 0.9±0.9 |

| HCT (%) | 45.7±6.9 | 48.7±8.1 | 47.6±8.4 | 48.5±2.1 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 14±2.5 | 14±2.5 | 14.3±2.6 | 15.1±0.7 |

| WBC (1000/μL) | 11 230±4496 | 10 587±4987 | 12 300±4459 | 5750±2050 |

| AST (U/L) | 61.2±35.6 | 65.7±37 | 71.2±33.4 | 53.5±2.1 |

| ALT (U/L) | 74.8±42.3 | 80.7±44.1 | 87.3±39.4 | 69.5±3.5 |

| ALP (U/L) | 148.3±80.8 | 186.8±77.8 | 186.1±78.7 | 171±9.9 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 42.5±21.8 | 46±23.3 | 53.4±22.5 | 56±17 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 1.9±1.1 | 1.8±0.9 | 2±0.8 | 2±0.6 |

| CPK (U/L) | 327.2±144.8 | 289.1±155.8 | 321.5±140.1 | 236±227.7 |

PT: prothrombin time; PTT: partial thromboplastin time: INR: international normalized ratio; HCT: hematocrit; Hb: hemoglobin; AST: aspartate transaminase; ALT: alanine transaminase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; Cr: creatinine; CPK: creatine phosphokinase.

Snakebites by venomous snakes are one of the most important causes of injuries and deaths among accidents caused by venomous animal bites in many parts of the world, including Iran. Due to climate and geographical conditions and the existence of known species of venomous snakes in Iran, every year we see the occurrence of injuries caused by snakebites in different parts of the country. Proper knowledge of the clinical picture, complications of snake bites, and treatment is essential for the proper treatment of these patients.

Demographic analysis of patients in the present study showed that the majority of patients were male (73.2%) and the rest were female. The highest frequency was in the age group of 21–45 years. In Kassiri et al.'s study in Khoram-Shahr, 73.5% of the victims were male and most of the victims were in the age group of 41–50 years (27.4%).12 In Hafezi et al. study in Karoon, 73.5% of victims were male and related to the age group of 15–34 years.13 The study of Eslamian et al. who retrospectively studied snakebite in northwestern Iran during the 10 years shows that 77.6% of the patients were male.14 A study in Kashan by Dehghani et al. also revealed that 96% of snakebite cases were men and the highest rate of snake bites happened in the 15–24 years old age group.15 Hajati et al.'s study showed that 72.2% of patients were male and most of them were in the age range of 16–30 years.16 In Safavi et al.'s study, which examined the epidemiological indicators, symptoms, complications, and treatment of snakebite in patients of Noor Hospital in Isfahan, 79% of patients were male and most of them were in the age group of 15–40 years.17 In the study of Mohammadi Kojidi et al., which examined the clinical and laboratory findings of patients with snakebite in Gilan province, 71% of patients were male and the mean age of the population was in the middle age range (43 years).18 In the study of Ghaffari et al., out of 69 patients bitten by snakes and scorpions, 59.4% were men, most of whom were in the age range of 30–45 years.9 It seems that the lower frequency of male patients in the study of Ghaffari et al. compared to the present study and the study of Kajidi et al. may be due to cultural differences in the studied patients. The present and Kojidi et al. studies were performed in the north of the country and Ghaffari et al study have been done in the south of the country.9 The higher number of bites in men can be due to their occupation or daily activities, which causes them to be in open environments and puts them at greater risk of bites. The use of patients with scorpion stings in the study of Ghaffari et al. can be another reason for this difference.9 In the study of Zamani et al., which examined the epidemiology and estimated cases of snake and scorpion bites in patients referred to 22 Bahman Masjed Soleiman Hospital, 45% of patients were male and the mean age was 28.3 years.10

In the present study, 70.7% of snakebite time was related to morning and noon and 66.1% was related to spring and summer. Farzaneh et al. in a study in Ardabil defined that most of the snakebites occurred between 11 AM and 4 PM. Moreover, they defined spring and summer as the main seasons of snakebites.19 In the study of Ghaffari et al., about half of the referrals were in the summer.9 In the study of Mohammadi Kojidi et al., the highest frequency in terms of snakebite time was at noon (36%) and most of them were related to summer and spring (92%).18 Safavi et al. reported that most cases of bites have happened in the warm seasons of the year.17 In Kassiri et al.'s study also, spring (44.1%) and summer (44.1%) were the seasons with more snakebites occurrence and mostly happened between 6 PM and 12 AM.12

In the current study, the majority (82.5%) of people were engaged in agricultural work. In the study of Ghaffari et al., 76% of people were rural and engaged in agriculture.9 Safavi et al. showed that the highest frequency of jobs were agriculturalists or workers.17

In this study, the highest frequency of bites was in the lower extremities and right side. Similar to this study, Farzaneh et al. study showed that most of the snakebites (56.7%) happened on lower limbs and mostly in the right limbs (52.6%).19 In the study of Ghaffari et al., the most common site of bites was the lower limb.9 In the study of Mohammadi Kojidi et al., the highest frequency of bites was in the lower extremities.18 In the study of Kasturiratne et al., the lower and right limbs were the most common site of bites.17 A study by Hajati et al. also showed that 62% of the bite site was in the lower limb, which is consistent with the present study.16 In a study in Khorram-Abad, 60.8% of snakebites were in feet and 35.3% were in hands.12 On the other hand, in the study of Kargozar Sangani20 and Besharat et al.,21 the rate of bites in the upper extremity was higher, which may be due to differences in the nature of agricultural jobs and workers' jobs and the use or non-use of safety and auxiliary equipment such as gloves and suitable clothing.

In the present study, the highest frequency of local symptoms was related to bruising (17.8%), erythema (16.9%), pain (15.7%), edema (14.5%), subcutaneous bleeding (14.2%), and blisters (10.8%) and systemic symptoms included weakness and lethargy (24%), sweating (14.2%), hypotension (12.9%), and nausea and vomiting (11.1%). Hafezi et al.'s study showed that 74.6% of the victims complained of pain and 43.9% complained of edema.13 In the study of Mohammadi Kojidi et al., the most common symptoms related to subcutaneous bleeding, edema, and local pain.18 In Mir et al.'s study of snakebite patients, the most common symptoms were edema, pain, blisters, vomiting, and headache.22 A study in Ardabil city reported that all snakebite patients had pain, erythema, swelling, and ecchymosis bite symptoms. 40.3% suffered fainting, and nausea and vomiting were other prevalent symptoms.19 In the study of Hajati et al., the most common symptoms of patients were pain and swelling.16

The study of pre-hospital and hospital measures in the present study shows that despite being unscientific, in 4.3% of the cases, the cutting was made with a knife, and in 4% of cases, oral suction was performed. In the study of Besharat et al., in 35 cases (35%) local treatments were performed before referral to the hospital, such as cutting with a knife and suctioning with the mouth.21 Among all patients admitted due to snakebite in the present study, 1.8% required surgery, 3 cases of debridement, and 3 cases of abscess evacuation. In the study of Besharat et al. (40), 9% required surgery. In the study of Mohammadi Kojidi et al., 8% of the cases required surgery.18 For patients admitted to the present study, antivenom was used in 88.2% of cases. In the study of Kargozar Sangani, the rate of antivenom use was about 80%.20 According to Hafezi et al.'s study, 5–10 vials of antivenom were used for 96.5% of the victims.13 In the study, Mohammadi Kojidi et al. all cases received antivenom.18 In the Farzaneh et al. study, 5 vials of antidote were used for most of the patients with the mean of 5.1±1.3 vials.19 One of the reasons for the different rates of antivenom use in these studies could be due to the diversity of snake species in different geographical areas and some cases the lack of accurate information about the type of snake-bitten, which is associated with more caution among medical staff. In 33.8% of the snakebite patients studied in the present study, antibiotics were used, the highest frequency of which is related to the ciprofloxacin+clindamycin. This rate was 100% in the study of Mohammadi Kojidi et al.18 Reasons for using antibiotics or possibly differences in the criteria for starting antibiotics by the physician can be among the reasons for differences in the number of antibiotics used in different studies.

Evaluation of the final outcome of patients in the present study showed that there was no mortality among patients with snakebite, which is consistent with the findings of the study by Mohammadi Kojidi et al.18 In a study by Kasturiratne et al. in Pakistan, the annual prevalence of snake bites was 40 000, of which about 8200 died.17 In a study by Ariaratnam et al. in Sri Lanka, mortality from snakebites was reported to be around 2.8%.11 The difference in snakebite mortality rates in different studies can be attributed to various factors, such as the diversity and abundance of snakes in different geographical areas, access to health centers, and the knowledge and culture of individuals. The frequency of venomous snakes also varies in different geographical areas. Previous research conducted in Iran and other countries has consistently found that the majority of snakebite cases occur in men.13 This could be due to the fact that men are more likely to work or spend time in areas where snakebites are common, such as farms, deserts, and forests. However, it is important to note that gender differences in the clinical presentation of snakebite have been reported in some studies. Therefore, further analysis is needed to fully comprehend any potential gender differences in the clinical presentation and outcome of snakebites.

ConclusionThe results obtained in this study showed that the majority of patients were male and the highest frequency of snakebite was within the age group of 21–45 years. The most common site of bites was the lower limb which can be prevented by wearing boots while farming and in the mountains. Also, common local complications in patients included bruising, erythema, edema, and subcutaneous bleeding, and systemic complications such as weakness, lethargy, and sweating. Antivenom was used for most of the cases. No deaths were reported. Also, unscientific actions such as using a tourniquet, cutting with a knife, and suctioning with the mouth are still performed in cases that require further awareness and training.

LimitationsOne of the limitations of this study is the inherent limitation of retrospective studies on the possibility of recording errors. However, in this study, we tried to reduce this possibility as much as possible by increasing the number of years of study. Additionally, during our study, we collected valuable data on snakebite cases. However, we recognize that there are limitations to our study, such as the lack of evaluation of the time elapsed between the snakebite and hospital treatment. This factor could influence signs and symptoms and should be considered in future studies. Therefore, future studies should take into account the time elapsed between snakebite and hospital treatment, as well as the timing of antivenom administration, to improve patient outcomes.

We thank Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences for its support.