While opiate withdrawal syndrome (OWS) typically resolves within a few weeks, the discomfort in the initial days after discontinuing opioid use is intense. In this study, we compared the effects of 2 drugs, clonidine and dexmedetomidine, for treating OWS in patients admitted to the Toxicology ICU at Loghman-e Hakim Hospital.

MethodsWe collected patient information for individuals diagnosed with OWS in this clinical trial study. Fifty-two patients, matched based on the type of drug use (methadone, opiate, heroin), were included and divided into 2 groups. We compared the clinical effects of 2 drugs, dexmedetomidine and clonidine, on OWS symptoms using the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). The dexmedetomidine group received a dosage of 0.5 mcg/kg/h continuous IV infusion; not to exceed 24 h, while the clonidine group received 1.2 mg per day for 24 h. We completed the COWS standard checklist and compared the results after 0, 12, and 24 h.

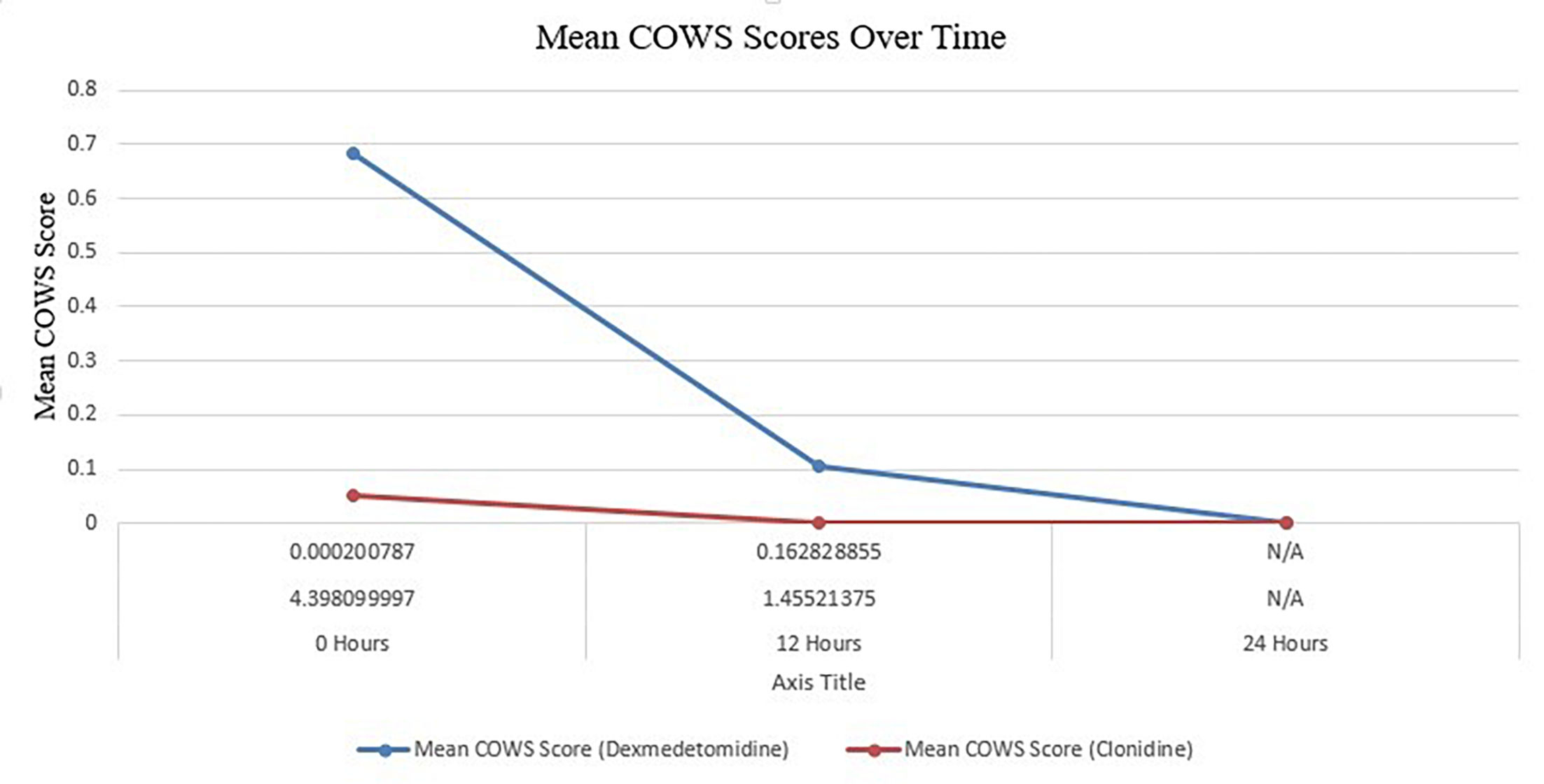

ResultsAt Zero hours' patients who were administered dexmedetomidine had a significantly higher average COWS score of 0.684, compared to a score of 0.053 for patients who received clonidine (p-value=.000201). At the 12-h, the distinction between the 2 treatment groups was no longer statistically significant, as evidenced by a p-value of .162829 (dexmedetomidine: 0.105 vs. clonidine: 0.000).

ConclusionsThe results suggest that dexmedetomidine is superior to clonidine in reducing withdrawal symptoms. The study found that both medications had a significant decrease in COWS scores over time, indicating their effectiveness in alleviating withdrawal symptoms as time passed.

si bien el síndrome de abstinencia de opiáceos (SOW) generalmente se resuelve en unas pocas semanas, el malestar en los primeros días después de suspender el uso de opioides es intenso. En este estudio, comparamos los efectos de dos fármacos, clonidina y dexmedetomidina, para el tratamiento del síndrome de abstinencia de opiáceos (SOW) en pacientes ingresados en la UCI de Toxicología del Hospital Loghman-e Hakim.

MétodosEn este estudio clínico aleatorizado, se recopiló información de pacientes de personas diagnosticadas con síndrome de abstinencia de opiáceos. Se incluyeron y dividieron en dos grupos cincuenta y dos pacientes, emparejados según el tipo de consumo de drogas (metadona, opiáceos, heroína). Los efectos clínicos de dos fármacos, dexmedetomidina y clonidina, sobre los síntomas del síndrome de abstinencia de opiáceos se compararon mediante la Escala Clínica de Abstinencia de Opiáceos (COWS). El grupo de dexmedetomidina recibió una dosis de 0,5 mcg/kg/h en infusión intravenosa continua; no exceder las 24 horas, mientras que el grupo de clonidina recibió 1,2 mg/día repartidos durante 24 horas. La lista de verificación estándar COWS se completó y comparó a las 0, 12 y 24 horas.

ResultadosEn las horas cero, los pacientes a los que se les administró dexmedetomidina tuvieron una puntuación COWS promedio significativamente mayor, de 0,684, en comparación con una puntuación de 0,053 para los pacientes que recibieron clonidina (p = 0,000201). A las 12 horas, la distinción entre los dos grupos de tratamiento ya no era estadísticamente significativa, como lo demuestra un p de 0,162,829 (dexmedetomidina: 0,105 frente a clonidina: 0,000).

ConclusionesLos resultados sugieren que la dexmedetomidina es superior a la clonidina para reducir los síntomas de abstinencia. La investigación demostró una disminución significativa en las puntuaciones COWS de ambos medicamentos con el tiempo, lo que indica su eficacia para aliviar los síntomas de abstinencia conforme avanzaba el tiempo.

Opiate withdrawal syndrome (OWS) possibly arises through the following pathway. Opiates reduce GABA-mediated inhibitory impacts on dopamine-releasing neurons via binding to Mu Opiate receptors on inhibitory interneurons. This leads to the release of large amounts of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, which is the main pleasure center of the brain.1,2 Exposure to opioids for a long time raises the dopaminergic neurons threshold, needing augmented amounts of opioid stimulus for releasing dopamine. Therefore, the lack of high opioid stimulus with high thresholds for dopamine release results in withdrawal symptoms.1–3

The effective factors in the occurrence of withdrawal syndrome include the length of the consumption period, the type of consumption, the frequency of consumption, the amount, and the type of substance consumed.4–6 The onset of withdrawal symptoms is 1–7 days for short-acting opioids (such as hydromorphone or oxycodone) and 7–10 days for long-acting opioids (such as methadone or buprenorphine).6 The types of symptoms of OWS may vary in different individuals. The commonly reported symptoms of OWS include pain, muscle spasms, tremor, abdominal cramps, anxiety, insomnia, diarrhea, sweating, gooseflesh, irritability, abdominal cramps, heart pounding, pupillary dilatation, hot flashes, rhinorrhea, lacrimation, etc.7,8

The locus coeruleus at the base of the brain is believed to be the main site in the brain that initiates OWS. The neurons in the locus coeruleus are noradrenergic and the number of opioid receptors is increased in them. The locus coeruleus is the core basis of NAergic innervation of the limbic system as well as the cerebral cortex and cerebellum. The activity of NAergic in neurons of the locus coeruleus, an opioid receptor-related mechanism, is a major site of drug withdrawal symptoms.9,10

Clonidine, an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, is a safe and effective non-narcotic treatment for OWS and exerts its effects by reducing noradrenergic activity. Clonidine reduces the signs and symptoms of withdrawal syndrome such as anxiety, irritability, anger, and restlessness in patients dependent on opium and opioids.11

Dexmedetomidine is the S-enantiomer of medetomidine, employed as a veterinary sedative. It is an imidazole derivative with a highly selective α2-adrenergic agonist. It is 8 times more selective for the α2-adrenergic receptor than clonidine. Dexmedetomidine also has anticongestive and anti-sialagogue effects due to its action on peripheral α2 adrenergic receptors. Dexmedetomidine suppresses shivering, possibly due to agonism of α2 receptors in the hypothalamus.12 The sedative effect produced by dexmedetomidine through the activation of endogenous sleep pathways closely resembles the physiological sleep state. Dexmedetomidine is probably associated with a decrease in cerebral blood flow without significant changes in ICP (intra cranial pressure) and CMRO2 (cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen). It has the potential to lead to the development of tolerance and dependence.13

The Loghman-e Hakim Hospital, which will host this study, is located in a densely populated region of Tehran with a diverse demographic makeup. Each year, the hospital admits a considerable number of patients with intoxication-related problems, reflecting the greater issue of substance addiction in the area. Last year, the Toxicology ICU treated about 1200 cases of drug intoxication, with opioids accounting for the majority of them. The prognosis for these patients varies greatly depending on the type and quantity of drug consumed, the timing of medical intervention, and the presence of underlying medical conditions. Understanding these dynamics is crucial because they have a direct impact on therapeutic strategies for treating opiate withdrawal, which is the focus of our current study. This backdrop highlights not just the urgency and necessity of our research, but also the hospital's critical role in serving the health needs of this patient population.

While OWS usually resolves after 5–14 days, discomfort in the first few days after stopping the use of opioids is intense. Consequently, without proper treatment, many patients are unable to stop consumption of opioids completely. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to compare the effects of 2 drugs, clonidine and dexmedetomidine, in the treatment of OWS in patients admitted to the Toxicology ICU of Loghman-e Hakim Hospital.

Materials and methodsStudy design and participantsThe Loghman Hakim Hospital in Tehran, Iran, hosted this randomized clinical study (IRCT registration number: IRCT20220305054196N3) from July to December 2023. We included individuals who had been brought to the intensive care unit for poisoning and had been diagnosed with OWS. In order to minimize confounding variables, patients who were 75 years of age or older, or who had significant underlying medical issues, were not included in the study.

InterventionThe subjects were administered either dexteremetomidine or clonidine in a random manner. A continuous intravenous infusion of dexmedetomidine was administered at a rate of 0.5 mcg/kg/h for a maximum duration of 24 h. Oral clonidine was administered at varying doses of 0.1 mg, 1.2 mg, and above, based on evaluations of heart rate and blood pressure.

Randomization and blindingA double-blind method was employed for randomization. The treatment allocations were hidden in opaque sealed envelopes labeled ‘A' for Clonidine and ‘B' for Dexmedetomidine. An objective administrator who was not involved in patient care personally chose these envelopes at random. No one knew which group they were in for therapy, so there was no room for bias.

Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS)The severity of opiate withdrawal was assessed using the COWS, an 11-item scale that measures symptoms such as tremors, sweating, anxiety, and pupil size. Assessments were conducted at the beginning (time 0), as well as 12 and 24 h after the administration.

PharmacokineticsTo appropriately assess the therapy effects, the pharmacokinetic characteristics of the medications were taken into account:

- •

Dexmedetomidine mostly metabolized in the liver via glucuronidation and hydroxylation, it has a half-life of about 6 min and 2–3 h, respectively, and demonstrates fast distribution and elimination.

- •

Clonidine has a bioavailability ranging from 75% to 95%, and its peak plasma concentrations are reached within 1–3 h after the administration. Additionally, it undergoes hepatic metabolism, with approximately 50%–70% of the administered amount being eliminated as metabolites in the urine. The drug's elimination half-life is 12–16 h.

The data were analyzed using STATA version 23. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. In order to compare groups, we utilized non-parametric testing, specifically the Chi-square test for categorical variables such as sex and drug type, and the Mann–Whitney U test for age. The medication's effectiveness was evaluated using a repeated measures ANOVA, with a significance level set at p<.05.

Ethical considerationsThe protocol for the study was approved by the ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1402.072). Informed permission was obtained for the study from each individual participant or their legal guardian.

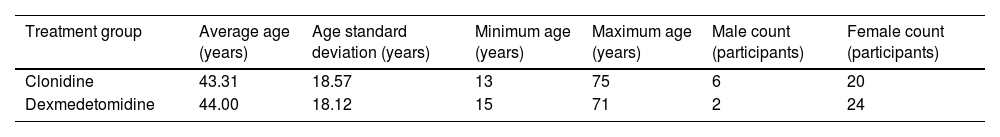

ResultsParticipant characteristicsTo ensure comparability between the 2 treatment groups, we meticulously assessed the patients' baseline characteristics. When we conducted the Mann–Whitney U test to look at age differences, we found no significant differences between the groups (U-value=332.00, p-value=.9197). The Chi-square test was also employed to assess the gender distribution, yielding a value of 1.33 (p=.2489, df=1), showing that the gender ratios in each treatment group were comparable. Additionally, the Chi-square test was employed to investigate the distribution of pharmaceutical types. The results revealed a value of 1.05 (df=5, p=.9582), showing that the groups had an equal distribution of medication types (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of participants by treatment group.

| Treatment group | Average age (years) | Age standard deviation (years) | Minimum age (years) | Maximum age (years) | Male count (participants) | Female count (participants) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clonidine | 43.31 | 18.57 | 13 | 75 | 6 | 20 |

| Dexmedetomidine | 44.00 | 18.12 | 15 | 71 | 2 | 24 |

This table outlines an equitable distribution across treatment groups, enhancing the reliability of subsequent comparisons.

To minimize potential confounding factors, participants were screened for primary opioids of abuse and other drugs. To rule out the possibility of non-opioid substances, such as alcohol, toxicological testing was carried out, and those who abused multiple substances were not included. The isolation of clonidine and dexmedetomidine's effects on opioid withdrawal symptoms relies heavily on this stringent screening procedure.

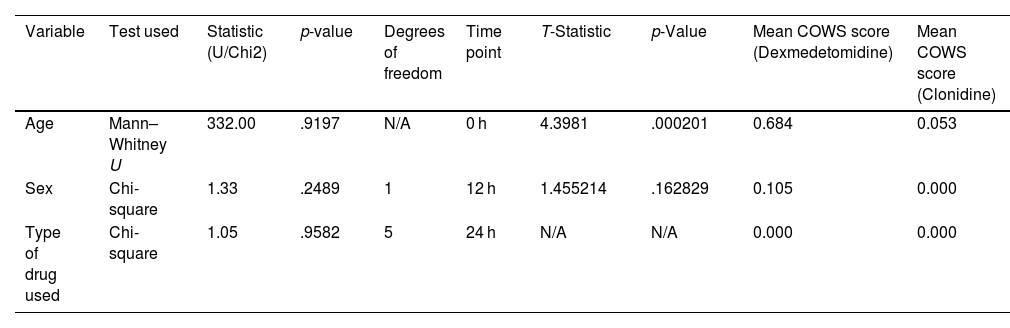

Comparative analysis of treatment efficacyThrough monitoring alterations in the effectiveness of treatment and the initial features of the subjects, we were able to provide more evidence that our methodology was strong and reliable. Table 2 demonstrates that the early differences in withdrawal symptoms among the groups, as assessed by the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS), eventually became equal after treatment.

Baseline characteristics and comparative analysis of COWS scores.

| Variable | Test used | Statistic (U/Chi2) | p-value | Degrees of freedom | Time point | T-Statistic | p-Value | Mean COWS score (Dexmedetomidine) | Mean COWS score (Clonidine) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mann–Whitney U | 332.00 | .9197 | N/A | 0 h | 4.3981 | .000201 | 0.684 | 0.053 |

| Sex | Chi-square | 1.33 | .2489 | 1 | 12 h | 1.455214 | .162829 | 0.105 | 0.000 |

| Type of drug used | Chi-square | 1.05 | .9582 | 5 | 24 h | N/A | N/A | 0.000 | 0.000 |

The average COWS score of patients given dexmedetomidine was 0.684 at the beginning of treatment, whereas the score of those given clonidine was 0.053 (p=.000201). It appears that the effectiveness of both therapies in reducing withdrawal symptoms converges over time, as these differences were no longer significant by 12 h (p=.162829). There was either a universal alleviation of symptoms or a consistent reaction to both therapies since the average COWS score at 24 h was 0 for both groups. This outcome could suggest either a widespread lack of withdrawal symptoms or a consistent reaction to both therapies at this point (Fig. 1).

Table 2 and Fig. 2 provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of dexmedetomidine and clonidine in the treatment of opiate withdrawal. It provides specific information on the COWS scores at 3 important time intervals: 0, 12, and 24 h following the administration of the medications. Fig. 2 visually depicts the progression of withdrawal symptoms for each drug over the specified time intervals.

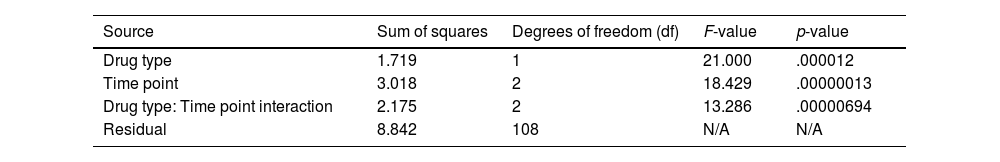

These data demonstrate that both dexmedetomidine and clonidine influence withdrawal symptoms, while their efficacy fluctuates over time. At the start, precisely at the 0-h mark, there was a clear disparity in the average COWS ratings between the 2 medicines, indicating a variation in their early impact on withdrawal symptoms. As time advances towards the 12- and 24-h intervals, the disparity in scores becomes less noticeable. This tendency suggests that the 2 medicines are becoming equally effective in reducing withdrawal symptoms as time goes by, as detailed in Table 3.

Analysis of mean COWS scores by drug type across time points in opiate withdrawal treatment.

| Source | Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom (df) | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug type | 1.719 | 1 | 21.000 | .000012 |

| Time point | 3.018 | 2 | 18.429 | .00000013 |

| Drug type: Time point interaction | 2.175 | 2 | 13.286 | .00000694 |

| Residual | 8.842 | 108 | N/A | N/A |

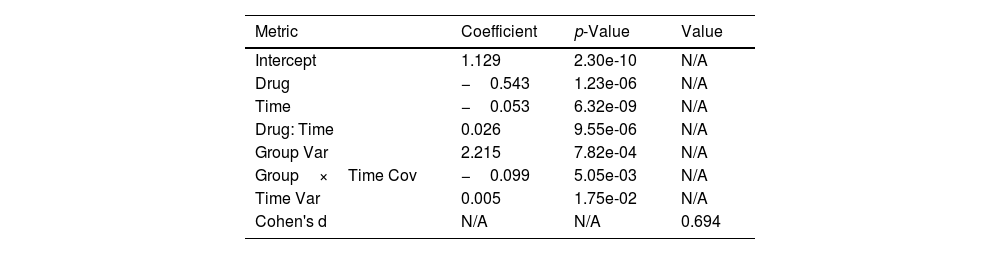

Both the effect size calculation (Cohen's d) and the Mixed-Model Repeated Measures (MMRM) analysis offer a thorough comprehension of the relative effectiveness of clonidine and dexmedetomidine in the treatment of OWS. Important results were obtained from the MMRM analysis which takes into consideration the repeated measures and innate correlations in the patient data (Table 4). Significant differences were observed in the scores on the COWS between patients receiving dexmedetomidine and clonidine treatment. This distinction implies that dexmedetomidine was superior to clonidine in terms of its ability to lessen withdrawal symptoms. Furthermore, the research showed that both medications' COWS scores significantly decreased with time, indicating how well they worked to relieve withdrawal symptoms. The rate of symptom reduction differed between the 2 medications during the examined period, according to the substantial interaction effect between drug type and time. This is an important finding because it emphasizes how medication efficacy in treating opiate withdrawal is dynamic, with dexmedetomidine exhibiting a more dramatic effect over time. In line with these findings, the effect size analysis performed with Cohen's d produced a value of around 0.69, falling between the medium and large effect size range. This figure represents a significant practical difference in the efficacy of the 2 medications in addition to supporting the statistical significance found in the MMRM analysis. A Cohen's d score in this range indicates that there is a clinically meaningful and statistically significant difference in the treatment results between clonidine and dexmedetomidine.

Comparative efficacy of clonidine and dexmedetomidine in treating opiate withdrawal syndrome: MMRM analysis and effect size estimation.

| Metric | Coefficient | p-Value | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.129 | 2.30e-10 | N/A |

| Drug | −0.543 | 1.23e-06 | N/A |

| Time | −0.053 | 6.32e-09 | N/A |

| Drug: Time | 0.026 | 9.55e-06 | N/A |

| Group Var | 2.215 | 7.82e-04 | N/A |

| Group×Time Cov | −0.099 | 5.05e-03 | N/A |

| Time Var | 0.005 | 1.75e-02 | N/A |

| Cohen's d | N/A | N/A | 0.694 |

The α-2 agonists as adjuncts to develop analgesia, sedation, as well as euphoria in a block of acute withdrawal symptoms in chronic opioid users and anesthesia practice have been used for years. The current study compares the effect of 2 of them, dexmedetomidine and clonidine in improving OWS. In general, the study demonstrates that the cohorts had similar baseline characteristics in terms of age, sex, and kind of drug used, indicating a well-balanced distribution. The balance is crucial in strengthening the study's methodological rigor and guaranteeing the validity of the findings obtained from the comparison of treatment effects.

Pharmaceuticals and ancillary treatment are among the various approaches of managing opiate withdrawal. Well-known opioid receptor antagonists that relieve withdrawal symptoms and encourage abstinence include methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. In addition, non-opioid medications such as clonidine and dexmedetomidine are utilized to address the noradrenergic hyperactivity associated with opioid withdrawal.

The result of the present study adequately depicts the changing dynamics of withdrawal symptom severity under 2 distinct treatment regimes. Patients treated with dexmedetomidine experience more reduction in withdrawal symptoms at the beginning. Nevertheless, as time progresses, the discrepancy in the efficacy of dexmedetomidine and clonidine in alleviating these symptoms diminishes, resulting in similar results by the 12-h mark. This research is crucial for comprehending the immediate impacts of these medications on OWS and offers useful insights for making well-informed therapeutic decisions in Toxicology ICU settings. The study's results emphasize that although both medicines are successful in treating opiate withdrawal, their effects on withdrawal symptoms differ significantly in the first few hours after being given. Nevertheless, the disparity between the 2 treatments gradually decreases over a 24-h timeframe, indicating that both medications eventually achieve a comparable degree of efficacy in alleviating symptoms of opiate withdrawal.

According to a thorough study of literature, while methadone and other traditional opioid agonists are effective, there is a risk of dependence. Clonidine and other non-opioid alternatives are non-addictive, although they may not be as effective as opioid-based therapy in relieving severe withdrawal symptoms.1,8 Consistent with this research, our investigation demonstrates that dexmedetomidine rapidly alleviates withdrawal symptoms, perhaps surpassing clonidine in efficacy, while avoiding the risks associated with opioid agonist dependence.

Furthermore, recent studies have examined the role of dexmedetomidine in various therapeutic scenarios, emphasizing its efficacy in assisting patients with pain management and mitigating withdrawal symptoms, all while reducing their dependence on traditional opioids.14 Our findings support the idea that dexmedetomidine could be a better alternative to clonidine in the initial stages of treating opiate withdrawal.

The required individualized strategies for opiate withdrawal therapy are demonstrated by these treatments' efficacy. The degree of symptoms, the patient's medical history, and their risk of dependence or misuse should all be taken into consideration while deciding on a course of treatment. The topic of opioid withdrawal management is now undergoing investigation with the primary objectives of optimizing treatment regimens and expanding the range of efficacious medicines accessible to medical professionals.

In a study by Manoharan et al. on the comparison of dexmedetomidine and clonidine as additives for spinal anesthesia on lower abdominal surgery candidates who were eligible for a sub-arachnoid block, the group who received dexmedetomidine plus hyperbaric levobupivicaine in comparison to the group who received clonidine plus hyperbaric levobupivicaine had similar onset, elongated blockade duration, postponed first rescue analgesia request, decreased rate of analgesics, as well as desired sedation accompanied by similar slight hemodynamic alterations like bradycardia and hypotension.15 In a randomized clinical trial study by Shaikh et al., the effect of epidural clonidine and dexmedetomidine in combined spinal epidural anesthesia with intrathecal levobupivacaine for perioperative analgesia was compared and it was demonstrated that dexmedetomidine epidurally with intrathecal levobupivacaine is a superior adjuvant in comparison to clonidine epidurally due to enhanced sedation, elongated analgesia, as well as low side-effects.16 Sardesai et al. compared dexmedetomidine and clonidine as adjuvants to intravenous regional anesthesia and found that dexmedetomidine meaningfully facilitates onset, delays recovery of sensory along with the motor block, elongates length of analgesia, besides more patients' satisfaction. Both dexmedetomidine and clonidine reduced tourniquet pain reasonably and had similar intra-operative fentanyl requirements.17 In a study by Swami et al., clonidine and dexmedetomidine were compared as an adjuvant to local anesthetic agents in supraclavicular brachial plexus block. The results revealed that dexmedetomidine when added to local anesthetic improved the length of sensory and motor block as well as the length of analgesia. The time for rescue analgesia was elongated in dexmedetomidine-receiving patients. In addition, compared with clonidine, dexmedetomidine improved the quality of the block.18

In a study in 2018, Mirakhshti et al. evaluated the effectiveness of dexmedetomidine in orthopedic surgeries. They performed this evaluation as a double-blind randomized clinical trial on patients with femoral neck fractures with a history of opium addiction who were candidates for surgery with spinal anesthesia. After induction of spinal anesthesia hyperbaric bupivacaine, dexmedetomidine, or normal saline was injected into the patients. After evaluations, they stated that there was no significant difference in the demographic and basic characteristics of the patients in the 2 groups. The average consumption of morphine during the recovery period up to 2 h after surgery did not show a significant difference between the 2 groups. However, the average consumption of opium within 24 h after surgery had a significant difference and was lower in the group receiving dexmedetomidine (p<.001).19 In another study, the efficacy of dexmedetomidine versus ketorolac as local anesthetic adjuvants was assessed in terms of the onset and length of infraclavicular brachial plexus block. In this clinical trial study, 111 ASA class I (A normal healthy patient) and II (A patient with mild systemic disease) who were candidates for elective surgery of the distal arm and forearm under subclavian brachial plexus block were evaluated. They observed that dexmedetomidine compared to ketorolac had better effects on the duration of sensory and motor block and the onset of motor block.20 In a study in 2016, Memari et al. evaluated the effect of dexmedetomidine on femoral nerve block after femoral shaft fracture. They conducted this study as a double-blind clinical trial on 64 ASA Class I, and II patients with femoral shaft fracture. The surgery was performed under general anesthesia and divided the patients into 2 groups. Based on their results, they have stated that topical dexmedetomidine can reduce the average heart rate, and reduce systolic and diastolic blood pressure within 3 h after surgery compared to the control group.21

α-2 agonists can create a sedative, euphoria as well as analgesic effects through the locus coeruleus whereas it is assumed that the spinal mechanism is the main path of creating analgesic effects of α-2 agonists.22,23 Dexmedetomidine in comparison to clonidine is about 8 times more selective in its affinity to alpha 2 adrenoreceptor. In addition, dexmedetomidine has motor block ability and greater sedation quality with no additional significant side effects.22,24 The withdrawal of opioids triggers high noradrenergic activities, therefore the use of α2 agonists, such as dexmedetomidine or clonidine, has been successful because of their favorable effects such as sedative activity, the lessening of the sympathetic nervous system activation, and the reduction in the opioids requirements which seems to be associated to their effect on the nucleus ceruleus.25

ConclusionUltimately, the amalgamated outcomes provide substantial evidence that dexmedetomidine could prove to be a more efficacious alternative to clonidine in the management of OWS within the scrutinized patient cohort. These findings give important insights that can guide treatment strategy selection in the context of the Toxicology ICU, with substantial implications for clinical practice. However, it is crucial to consider these findings in light of the particular study setting and the patient population at Loghman-e Hakim Hospital. It would be helpful to conduct additional studies, perhaps with a larger and more diverse cohort, to validate these results and determine their applicability to other patient populations.

FundingToxicological Research Center (TRC) of Loghman Hakim Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical statementThe study is approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with code IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1402.072. All authors read and approved the study. Written informed consent received from participants.

The authors would like to thank the Toxicological Research Center (TRC) of Loghman Hakim Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran for their support, cooperation, and assistance throughout the study. The researchers also thank and appreciate the support of Professor Latif Gachkar in the design and implementation of this research.