One of the effective factors in reducing postpartum mental illnesses, such as anxiety, is observing maternal rights and mothers' positive attitude about childbirth. The present study aimed to determine the relationship between maternal rights charter observance during labor and postpartum anxiety.

Materials and methodsThis was a cross-sectional study. We investigated the observance of maternal rights charter using a researcher-made questionnaire. Postpartum anxiety was investigated using Spielberger questionnaire. The relationship between these 2 factors was investigated via studying 160 eligible pregnant mothers admitted in Hazrat Zeinab, Hafez, and Shooshtari hospitals. Data were analyzed through SPSS software (version 16), using one-way ANOVA and Pearson correlation coefficient at the significant level of 5%.

ResultsThere a was a significant relationship between the delivery team members in terms of dimensions in the maternal rights charter (p=.003) and general dimensions (p=.001). This difference was in emotional (p=.001) and informational (p=.013) dimensions. There was no significant difference in physical dimension (p=.070). Among the participants, 93.75% had implicit anxiety and 83.75% had explicit anxiety.

ConclusionsFailure to observe maternal rights charter was associated with an increase in explicit and implicit postpartum anxiety. Maternal rights in the physical aspect were observed equally by the midwife instructor, staff, and residents. However, there was a difference in the emotional and informational dimensions of the members of the delivery team.

Uno de los factores eficaces para reducir las enfermedades mentales posparto, como la ansiedad, es el respeto de los derechos maternos y la actitud positiva de las madres ante el parto. El propósito de este estudio fue determinar la relación entre la observancia de la Carta de Derechos Maternos durante el parto y la ansiedad posparto.

Materiales y MétodosEste es un estudio transversal. Investigamos la observancia de la carta de derechos maternos utilizando un cuestionario elaborado por un investigador; La ansiedad posparto se investigó mediante el cuestionario de Spielberger. Además, se investigó la relación entre estos dos factores en 160 madres embarazadas ingresadas en los hospitales Hazrat Zeinab, Hafez y Shooshtari y fueron elegibles para su inclusión. Los datos se analizaron mediante el software SPSS (versión 16), utilizando ANOVA unidireccional y coeficiente de correlación de Pearson al nivel significativo del 5%.

ResultadosEntre los integrantes del equipo de parto en cuanto a las dimensiones de la carta de derechos maternos (p = 0,003) y dimensiones generales (p = 0,001) fue significativa. Esta diferencia se produjo en las dimensiones emocional (p = 0,001) e informativa (p = 0,013). No hubo diferencia significativa en la dimensión física (p = 0,070). El 93,75% de los participantes en este estudio tenía ansiedad implícita y el 83,75% tenía ansiedad explícita.

ConclusionesEl incumplimiento de la carta de derechos maternos se asoció con un aumento de la ansiedad posparto explícita e implícita. Los derechos maternos en el aspecto físico fueron respetados por igual por la partera instructora, el personal y los residentes. Sin embargo, hubo una diferencia en las dimensiones emocional e informativa de los miembros del equipo de entrega.

One of the most common and well-documented mental problems after childbirth is maternal anxiety with adverse effects on maternal–neonatal early interactions, spousal relationships, and the long-term development of the infant.1,2

The prevalence of postpartum anxiety has been reported as 12%–13% in some studies.3,4 On the other hand, the prevalence of anxiety in women is twice more than that of men due to their unique stress such as pregnancy and childbirth.5 Anxiety is a very unpleasant and often ambiguous feeling that is characterized by extreme fear or uncertainty about an unknown factor, often accompanied by symptoms such as headache, sweating, palpitations, restlessness, and shortness of breath.6

Studies show that protection and observance of women's rights during labor are divided into three general categories: (1) emotional support: respect for mother, compassionate care, etc.; (2) informational support and counseling: giving required information and trainings to mother in labor; and (3) physical support: attention to oral hygiene, nutrition, emptying the bladder, etc.7–9 According to the results of Ghani's study (2011) in Egypt, the greatest need of women (85%) during labor and delivery is related to protecting and observing their rights in the emotional domain.10

According to Renfrew et al., the quality of care, effective and respectful treatment, and skills of service providers are the most important and basic needs of women during childbirth.11 Considering the role of treatment staff in reducing postpartum mental illness and its effects on family health, postpartum support and its impact on postpartum mental health have been studied in different studies so far.12 Not respecting the rights of mothers and patients can cause serious health problems, and even endanger patients' lives and safety.

It also weakens the relationship between the healthcare workers and the sick person. This ultimately leads to a reduction in the effectiveness of services and effective patient care. Due to the limitations of the studies and the necessity of the above, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between maternal rights observance by each of the delivery team members in labor.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the relationship between the observance of maternal rights charter in labor and postpartum anxiety of mothers at Hazrat Zeinab, Hafez and Shooshtari hospitals in Shiraz, Iran.

Sample size and randomizationThe sample size was determined according to the objectives and type of study, previous studies13,14 in this field, and the following parameters: 95% confidence coefficient and 80% power and the minimum predicted correlation coefficient of 0.25. Using the formula, 130 subjects was estimated to participate. To increase the accuracy of sampling and intra-group analysis, the sample size was increased to 160 people.

The simple stratified sampling method was used. At first, the proportion of each classification relative to the population size of each maternity hospital was determined from the total sample size. Then, simple purposive sampling method was used in each classification. Thus, the researcher began referring to the mentioned hospitals at the time of the study and began sampling from those present individuals and moving to the next person if the selected person was not included in the sample for any reason. In university hospitals, maternal delivery can be performed by 3 different teams: a midwifery instructor with students, an obstetrics resident with medical students, and midwifery staff. In the same sample, 53 mothers were delivered by a midwifery instructor, 54 by an obstetrics resident, and 53 by the staff. The samples of each group were collected from 3 hospitals.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe study inclusion criteria were pregnant woman's consent to participate in the study, pregnant woman's residence in Shiraz, vaginal delivery, pregnancy age between 37 and 42 weeks, no maternal surgical internal diseases (according to records), having medical history of normal delivery during pregnancy and childbirth, no current and past psychological illness (according to the records and self-report), not using psychotropic medications, not having a poor history of midwifery (such as recurrent abortion, stillbirth, and intrauterine fetal demise), and not using assisted reproductive methods. The study exclusion criteria included unwillingness to continue to cooperate and physical or psychological illnesses during the study (based on patient records and self-report).

Subject population and interventionHaving referred to the aforementioned centers, the researcher first explained the importance of the study to eligible mothers 12–24 h after their delivery. Then, the sampling was conducted from among mothers who completed the informed consent form to participate in the project. The delivery factor (midwife, staff, and resident) of each sample was determined by the researcher. The researcher completed the questionnaires of maternal rights and postpartum anxiety according to mothers' answers.

In this study, Spielberger questionnaire and researcher-made maternal rights charter questionnaire were used. The questionnaire consists of 27 questions based on articles and books designed and developed in accordance with the Maternal Rights Charter in labor and delivery (published by the Iranian Ministry of Health) in 3 dimensions: physical support, emotional support, and informational support. Face validity and content validity were confirmed by 10 experts in this field. By studying 40 individuals, we calculated the Cronbach's alpha as 91%. The validity and reliability of the Spielberger questionnaire has been confirmed in foreign studies.15,16 The validity and reliability of this study was also confirmed in a previous study. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 86%.17

Data analysis methodTo analyze the data, we used descriptive statistical methods, multivariate analysis of variance, and Bonferoni test to compare the scores of maternal rights charter observance in 3 dimensions of informational, physical, and emotional. One-way ANOVA and post hoc analysis were used to compare the score of maternal rights charter observance in general by each of the delivery team members. Chi-square test was used to determine the frequency of mothers with explicit and implicit postpartum anxiety in general & low, medium, and high levels of postpartum anxiety in 3 groups of residents, midwifery instructor, and staff. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to determine the correlation between the scores of maternal rights charter and postpartum anxiety at the significant level of 0.05. Data were analyzed by SPSS software (version 16).

Ethical considerationsThis research project was approved by the local Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Project Number: 19245, Ethics ID: IR. SUMS. REC.1398.525). Permission to conduct the research was given by the authorities of the related units, and the full description of the study objectives were provided to the authorities. Also, the patients were given a verbal lecture and written information about the goals and approach of the project. After obtaining the patients' agreement to participate, the researchers introduced themselves to the participants. Afterwards, all the participants filled out an informed consent form prior to their attendance in the study and were assured that all research information was kept confidential.

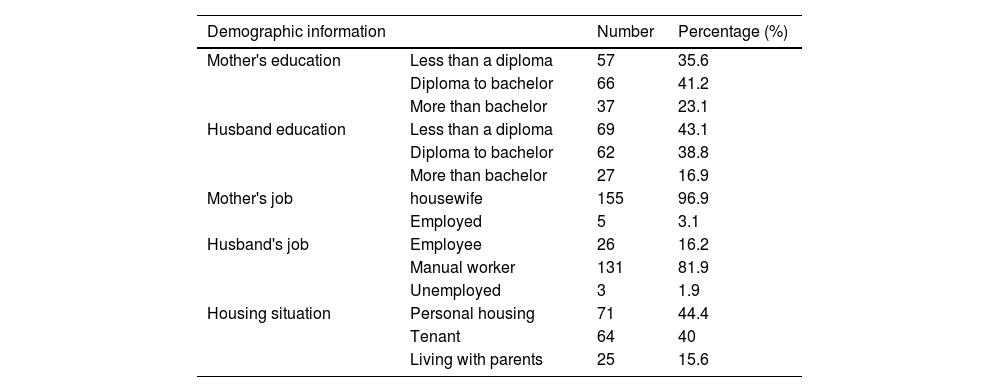

ResultsThe mean age of the mothers and fathers who participated in this study was 28.21±5.89 and 33.57±5.38, respectively. Their demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. It should be noted that the gestational age of the mothers participating in this study ranged from 37 to 42 years (Table 1). According to the results of this study, observance of maternal rights charter by each member of the delivery team was associated with reduced explicit (r=−874, p<.001) and implicit (r=−876, p<.001) postpartum anxiety. Explicit anxiety was directly correlated with implicit anxiety (r=0.963, p<.001). There was also no statistically significant difference between the delivery team members in terms of explicit and implicit postpartum anxiety. Overall, 83.75% of the subjects in this study had explicit and 93.75% had implicit postpartum anxiety (Table 2).

Demographic characteristics of the mothers participating in this study and their spouses.

| Demographic information | Number | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother's education | Less than a diploma | 57 | 35.6 |

| Diploma to bachelor | 66 | 41.2 | |

| More than bachelor | 37 | 23.1 | |

| Husband education | Less than a diploma | 69 | 43.1 |

| Diploma to bachelor | 62 | 38.8 | |

| More than bachelor | 27 | 16.9 | |

| Mother's job | housewife | 155 | 96.9 |

| Employed | 5 | 3.1 | |

| Husband's job | Employee | 26 | 16.2 |

| Manual worker | 131 | 81.9 | |

| Unemployed | 3 | 1.9 | |

| Housing situation | Personal housing | 71 | 44.4 |

| Tenant | 64 | 40 | |

| Living with parents | 25 | 15.6 |

Relationship between the score of maternal rights charter observance and postnatal anxiety and between explicit and implicit anxiety.

| Maternal rights charter | State anxiety | Trait anxiety | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal rights charter | r=−0.874p<.001 | r=−0.876p<.001 | |

| State anxiety | r=−0.874p<.001 | r=0.963p<.001 | |

| Trait anxiety | r=−0.876p<.001 | r=0.963p<.001 |

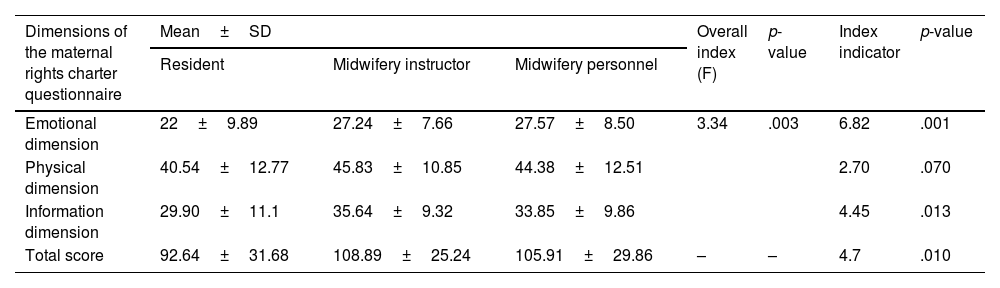

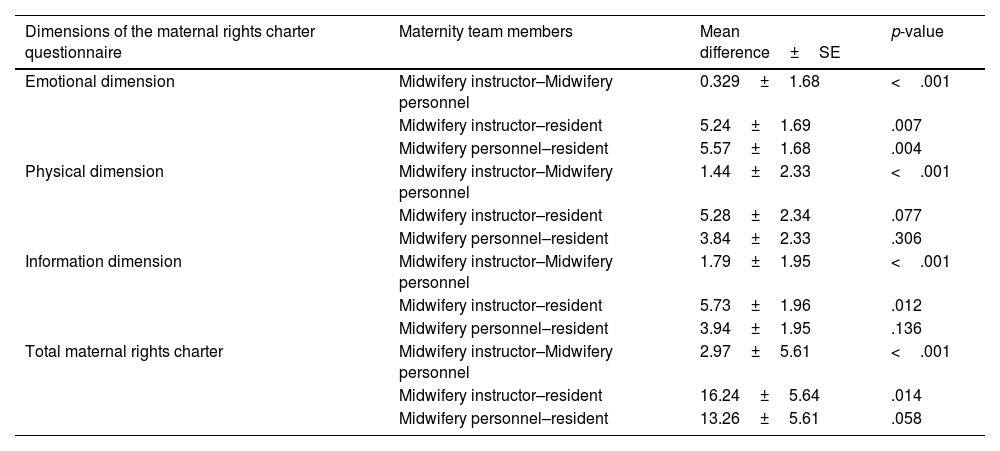

There was a significant difference between the maternal team members in terms of the dimensions of maternal rights charter observance (p=.003) and in general terms (p=.001). This difference was observed in the informational (p=.013) and emotional (p=.001) dimensions. However, there was no significant difference in physical dimension (p=.070). A difference was observed in informational dimension between the midwifery instructor and resident (p=.012). In the emotional dimension, there was a difference between midwifery instructor and resident (p=.007), and between midwifery and resident staff (p=.004). As to maternal rights charter observance in general, there was a significant difference between the midwifery instructor and resident (p=.014) (Tables 3, 4).

Comparison of the frequency of the score of maternal rights charter observance in the emotional, informational, and physical and general dimensions by each member of delivery team (midwife instructor, resident, and midwifery personnel).

| Dimensions of the maternal rights charter questionnaire | Mean±SD | Overall index (F) | p-value | Index indicator | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident | Midwifery instructor | Midwifery personnel | |||||

| Emotional dimension | 22±9.89 | 27.24±7.66 | 27.57±8.50 | 3.34 | .003 | 6.82 | .001 |

| Physical dimension | 40.54±12.77 | 45.83±10.85 | 44.38±12.51 | 2.70 | .070 | ||

| Information dimension | 29.90±11.1 | 35.64±9.32 | 33.85±9.86 | 4.45 | .013 | ||

| Total score | 92.64±31.68 | 108.89±25.24 | 105.91±29.86 | – | – | 4.7 | .010 |

Comparison of the delivery team members in terms of the observance of maternal rights charter in 3 emotional, physical, and informational dimensions and general dimensions

| Dimensions of the maternal rights charter questionnaire | Maternity team members | Mean difference±SE | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional dimension | Midwifery instructor–Midwifery personnel | 0.329±1.68 | <.001 |

| Midwifery instructor–resident | 5.24±1.69 | .007 | |

| Midwifery personnel–resident | 5.57±1.68 | .004 | |

| Physical dimension | Midwifery instructor–Midwifery personnel | 1.44±2.33 | <.001 |

| Midwifery instructor–resident | 5.28±2.34 | .077 | |

| Midwifery personnel–resident | 3.84±2.33 | .306 | |

| Information dimension | Midwifery instructor–Midwifery personnel | 1.79±1.95 | <.001 |

| Midwifery instructor–resident | 5.73±1.96 | .012 | |

| Midwifery personnel–resident | 3.94±1.95 | .136 | |

| Total maternal rights charter | Midwifery instructor–Midwifery personnel | 2.97±5.61 | <.001 |

| Midwifery instructor–resident | 16.24±5.64 | .014 | |

| Midwifery personnel–resident | 13.26±5.61 | .058 |

According to the results of this study, failure to observe the rights of the mother in labor was associated with increased postpartum anxiety in each of the delivery team members. In this regard, according to the results of the study carried out by Giakoumaki and Bell, support for mothers in labor and their positive feeling and satisfaction with childbirth are effective in reducing postpartum anxiety.18,19 In fact, women evaluate the experience of delivery based on the services provided to them and the observance of their rights during delivery. In the present study, maternal rights in labor were formulated in 3 dimensions of emotional, physical, and informational, and their relationship with postpartum anxiety was investigated. However, previous studies have examined the effect of postpartum support on reducing postpartum anxiety.20,21

As to supports during labor, previous studies have generally examined the relationship between one maternal dimension (emotional dimension) in labor and postpartum anxiety.13,22 However, the present study examined the relationship between maternal rights in 3 emotional, physical, and informational dimensions with postpartum anxiety.

In the present study, maternal rights in physical dimension were observed equally by the midwifery instructor, midwifery staff, and resident. This indicates that the delivery team members are responsible for their profession and play an active role in maintaining standards and performing their duties. In the Bahri's study (2014) in Gonabad, 93% of the mothers were satisfied with the physical support they received from staff during labor.23 In Safayi's study (2014) in Mashhad, maternal rights were observed to a certain extent from the perspective of the midwife, midwife's colleague, head of maternity ward, and the mother.14

Maternal rights score by the midwifery instructor in the informational dimension were also higher than those of other members of the delivery team. This means that the midwife, in her interactions with the mother, has provided the mother with required information at different stages of delivery. In Bahri's study, 92% of the mothers were also satisfied with the information they received from the staff,23 but in Khodakarami study, women did not have adequate information support.24 More observance of maternal rights by the midwife instructor may be due to her greater awareness of maternal rights. Because being aware of the provisions of the charter of maternal rights obliges the doctors and midwives to observe them. Respect for dignity and rights of pregnant mothers is the basis of midwifery care which is a step toward increasing the mothers' satisfaction with the services provided by the healthcare staff.25 It appears that increased maternal satisfaction with the delivery process may also be effective in increasing the fertility rates. On the other hand, respecting the rights and giving the information needed to the patients is a primary and ethical duty. Also, contrary to the existing beliefs, patient's awareness does not lead to increased emotional and uncontrolled demand, rather it leads to mutual behavior of the patient and provider in a more balanced way that moderates mutual expectations.26 In some cases, physicians find it unnecessary to provide information to the patient. In a study in Lithuania, only 50% of the physicians found it necessary to provide the patients with information on diagnosis and treatment.27 In emotional dimension, maternal rights were observed by midwifery instructors and staff more than the residents. Establishing a good relationship with patients is an important part of nursing and midwifery care and can promote health outcomes and patients' satisfaction. Residents' less observance of maternal emotional rights may be due to their focus on health issues. In the case study of Kazemnezhad, mean score of observance of the patient's emotional rights by physicians and nurses was reported as 1.67±0.74 and 2.13±1.05, respectively. This indicates that the patient's emotional rights are less observed by physicians than nurses.28 In Bahry's study, mothers received less emotional support (74%) from the staff than other supports.23 Among the causes of the failure to observe the rights of patients completely by doctors and paramedics, we can refer to their low level of awareness and attitude toward this issue and their ignorance of the consequences of not observing the emotional rights of the mother on the health of the infant, the mother and the family in general.28

One of the strengths of this study was comparison of the score of maternal rights observance in 3 emotional, physical, and informational dimensions by the members of the delivery team (midwives, residents, and staff) as well as the relationship of observing the rights of the mother in labor with postpartum anxiety. Limitations of this study include lack of participation of some mothers due to postpartum fatigue. This lengthened the sampling period.

Given the role of midwives and obstetricians in the healthcare system, the results of this study can be used to inform the medical staff about maternal rights in labor. Also, by observing maternal rights in labor, the effects of postpartum anxiety on the health of the mother, infant and family can be prevented.

The results of this research in the field of midwifery and professionalism can be used to prepare a pregnant woman to accept the role of mother and recognize her rights. Also, managers in any part of the society, especially in the field of nursing and in intensive care units, can benefit from the results of such research in order to improve maternal and neonatal health and shorten the length of hospital stay of the infants. Besides, presenting the results of this study to midwives and obstetricians and gynecologists will play an important role in informing them about maternal rights in labor and will lead to mental health of the mothers, infants, and families. One of the problems of the research was the restriction of mothers' cooperation in completing the postnatal questionnaires. In some cases, due to the mother's unfavorable conditions, the researcher referred several times a day to complete the questionnaires.

It is recommended to conduct further research on the effect of teaching the charter of pregnant women's rights to midwives, obstetrician, and obstetrical residents on the level of maternal satisfaction, maternal anxiety, complications during labor, and postpartum, and also investigate the effects of mothers' awareness of the rights of pregnant women.

ConclusionThere was a relationship between increased maternal anxiety and lack of observance of maternal rights by each member of the delivery team. However, there was no significant statistical difference between the members of the delivery team in terms of trait and state of covert postpartum anxiety; and the maternal rights charter was observed equally in physical aspect by the midwife, staff, and resident. However, in the emotional and informational dimension, maternal rights were more observed by the midwifery instructors and midwifery staff than the residents. Generally, it can be said that the midwifery instructors observed maternal rights more than the residents. Therefore, it is suggested that workshops should be held on how the midwives and other service providers should interact with the pregnant mother.

FundingThis work was supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Ethical considerationsThe ethics committee approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Project Number: 19245, Ethics ID: IR. SUMS. REC.1398.525).

This article was extracted from Ms. Marziye Shahpari's thesis (Project Number: 19245), which was approved and sponsored by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. The authors would like to thank Shiraz University of Medical Sciences and The Center for Development of Clinical Research of Namazi Hospital for their cooperation in data analysis and Dr. Nasrin Shokrpour for editorial assistance.