Actinotignum schaalii and the genus Aerococcus are considered emerging pathogens, since their isolation has been rising the last years thanks to the improvement of diagnosis techniques, such as the implementation of MALDI-TOF in microbiology laboratories for routine. Their patogenicity is nowadays well described in urinary tract infections affecting susceptible individuals, although both have been isolated from other biological samples. The aim of our study is to evaluate the impact of using mass spectrometry technology on the frequency of isolation of Aerococcus spp and A. schaalii in our hospital.

MethodsFrom January 2014 and December 2015 44.654 urines were collected in our laboratory from patients that were expected to have an UTI. Samples were processed using a flow cytometer and cultured if applicable. After 48h, microbial growth was assessed. Due to the suspicion of an Aerococcus spp or A. schaalii infection identification test was performed using Vitek2 until 2014 and MALDI-TOF from 2015.

ResultsBetween the period of study, a total of 35 Aerococcus spp/A. schaalii isolates were collected from 34 patients. Six isolates were identified by Vitek2 and the other 29 were identified by MALDI-TOF. Out of 34 patients, 33 had at least one risk factor including age >65 years, immunosuppression or cancer, abnormality of the genitourinary tract, recurrent UTI, diabetes or a catheterization.

ConclusionsSince the implementation of the MALDI-TOF in the laboratory the isolation of Aerococcus spp/A. schaalii has increased almost five times. The most frequent patient corresponds to an elderly patient with recurrent UTI and cancer.

Actinotignum schaalii y el género Aerococcus son considerados patógenos emergentes debido al aumento en los últimos años de su aislamiento gracias a la mejora de las técnicas diagnósticas, como la implementación del MALDI-TOF en la rutina de los laboratorios de microbiología. Su patogenicidad está bien descrita en las infecciones del tracto urinario (ITU) en individuos susceptibles, aunque los dos géneros se han aislado también en otras muestras biológicas. El objetivo de nuestro estudio es evaluar el impacto del uso de la espectrometría de masas en la frecuencia de aislamiento de Aerococcus spp/A. schaalii en nuestro hospital.

MétodosDesde enero 2014 a diciembre 2015 se recibieron 44.654 orinas en nuestro hospital procedentes de pacientes con sospecha de ITU. Las muestras fueron procesadas por citometría de flujo y sembradas según criterios establecidos. Pasadas 48h, se evaluó el crecimiento. Ante la sospecha de infección por Aerococcus spp/A. schaalii, se realizó un test de identificación con Vitek2® hasta 2014 y con MALDI-TOF desde 2015.

ResultadosDurante el periodo de estudio se registraron 35 aislamientos de Aerococcus spp/A. schaalii correspondientes a 34 pacientes. Seis aislados se identificaron por Vitek2® y 29 por MALDI-TOF. De los 34 pacientes, 33 tenían como mínimo un factor de riesgo (>65 años, inmunosupresión o cáncer, anormalidades del tracto urinario, ITU recurrente, diabetes o cateterismo).

ConclusionesDesde la implementación del MALDI-TOF en el laboratorio, el aislamiento de Aerococcus spp/A. schaalii ha aumentado 5 veces. El perfil más afectado es el de un individuo de edad avanzada con ITU recurrentes y cáncer.

Urinary tract infections (UTI) affect 150 million people each year worldwide1; and about 1 out 3 women will have had at least 1 episode of UTI requiring antimicrobial treatment by the age of 24 years.2 The most common pathogens are gram-negative bacteria found in 75–90% of cases. Among these, the most frequent causative agent is Escherichia coli followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gram-positive bacteria including Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Enterococcus faecalis and group B Streptococcus are responsible for the remaining proportion. Nevertheless, they are particularly common among the elderly, pregnant women or in individuals who have other risk factors for UTI such as structural or functional alterations of the urinary tract (often associated to catheterization), or other underlying renal, metabolic or immunological disorders.3,4

Nowadays, other rare, misclassified and underreported gram-positive bacteria are emerging, coinciding with the implementation of a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) system in the microbiology laboratories for routine identification.5–9Aerococcus spp and Actinotignum schaalii (formerly Actinobaculum schaalii10) exemplify this fact.

Several causes can explain why these organisms have been overlooked. A. schaalii is a gram-positive and facultative anaerobic coccoid rod and it is part of the urogenital flora and skin of healthy patients.11 It has a slowly (48h) and tedious growth requiring blood-enriched media and an anaerobic or 5% CO2-supplemented atmosphere. These conditions are not usually achieved in routine isolation, especially from urine. Indeed, nitrate reductase activities are negative. In addition, its tiny and gray colonies could be dismissed as a contaminant or overgrown by other bacteria.3,5–7

Aerococcus spp are gram-positive cocci showing a cluster organization in Gram stain although before catalase test they look like streptococci. The normal habitat of the human pathogenic aerococci is not known, but they occur both as a part of the normal flora of the human urinary tract and of the human oral flora of patients receiving cytostatic drugs. By the morphology of their colonies they can be confused with viridans streptococci.9

Moreover, in the pre-molecular diagnostic era identification was performed using standard phenotypic methods such as API system and Vitek 2 Compact (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) which did wrongly distinguish the two species.6,9 Indeed, some authors consider biochemical reactions inappropriate for aerococci determination.9

Performing direct examination of urine samples with Gram stain when there is significant leukocyturia allows microbiologists to detect the presence of gram-positive bacteria in order to cultivate them in suitable conditions (i.e. onto gram-positive selective media, colistin-nalidixic acid agar, incubated under 5% CO2).5

The aim of our study was to evaluate the utility of MALDI-TOF to identify A. schaalii and Aerococcus spp by comparing the frequency of infection due to these bacteria over 2 years in Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital (HUGTiP, Badalona, Spain) before and after its introduction in our laboratory and to describe demographic data of the patients.

Material and methodsStudy designThis is a retrospective observational study designed to assess the evolution of the diagnosis of UTI at the Microbiology Department of the HUGTiP with two different techniques: Vitek 2 Compact (BioMérieux) until 2014 and MALDI-TOF (Bruker Daltonics) from 2015.

Study population and clinical samplesDuring the period January 2014–December 2015, our hospital's clinical microbiology laboratory received 44.654 urines to be processed. These samples were collected from patients that were expected to have an UTI (i) coming from the emergency department or hospitalized at HUGTiP (21.722 urines) and (ii) from primary care centers (22.932 urines). All urine samples were collected in 5mL sterile tubes and stored without preservatives for a maximum of 4h at 4°C before processing.

Urine samples processingUrine samples were processed using the Sysmex UF-1000i flow cytometer (TOA Medical Electronics, Kobe, Japan). This stains the urine particles with a fluorescent dye, allowing them to be classified into white blood cells (WBC), red blood cells (RBC), epithelial cells (EC), bacteria (BAC) and yeasts (YEA) by impedance, scattering and fluorescence. This version has also an independent channel for bacteria.

All the samples from the HUGTiP were cultured with a 10μL loop onto chromogenic chromID® CPS® Elite plates (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) whereas only those samples considered positives (>40WBC/μL or 500BAC/μL by flow cytometry as established by previous studies12) from primary care centers were cultured. All samples were incubated for 24–48h at 37°C under aerobic conditions. Additionally, samples from the HUGTiP with >40WBC/μL by flow cytometry were Gram stained. When gram-positive bacteria with clinical significance were detected selective plates such as colistin-nalidixic acid plate were cultivated 48h under 5% CO2.

After this time, microbial growth was assessed by counting the number of colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) and by making a morphological recognition of the colonies. Clinical reports were collected to determine the pathogenic role of the isolate. Due to the suspicion of an Aerococcus spp or A. schaalii infection an identification test was performed: until 2014 was used the Vitek 2 (Bio-Mérieux, France) and from 2015 is used the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics, Leipzig, Germany).

Ethical approval from the Ethics Committee Research of Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital Ethics Committee was obtained (PI-17-165) and the need for informed consent was waived.

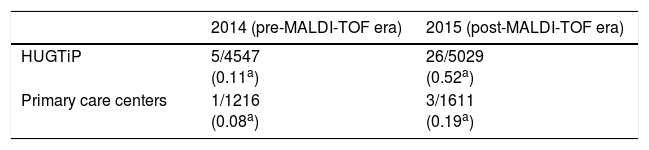

ResultsBetween January 2014 and December 2015, a total of 35 Aerococcus spp or A. schaalii isolates were collected from 34 patients. Six isolates were identified by Vitek2 (Bio-Mérieux, France) in 2014, and the other 29 were identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) in 2015. Out of 35 episodes, 4 correspond to patients from primary care centers and 31 were HUGTiP patients. The evolution in the frequency of Aerococcus spp or A. schaalii isolates before and after the introduction of the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics, Germany) is summarized in Table 1.

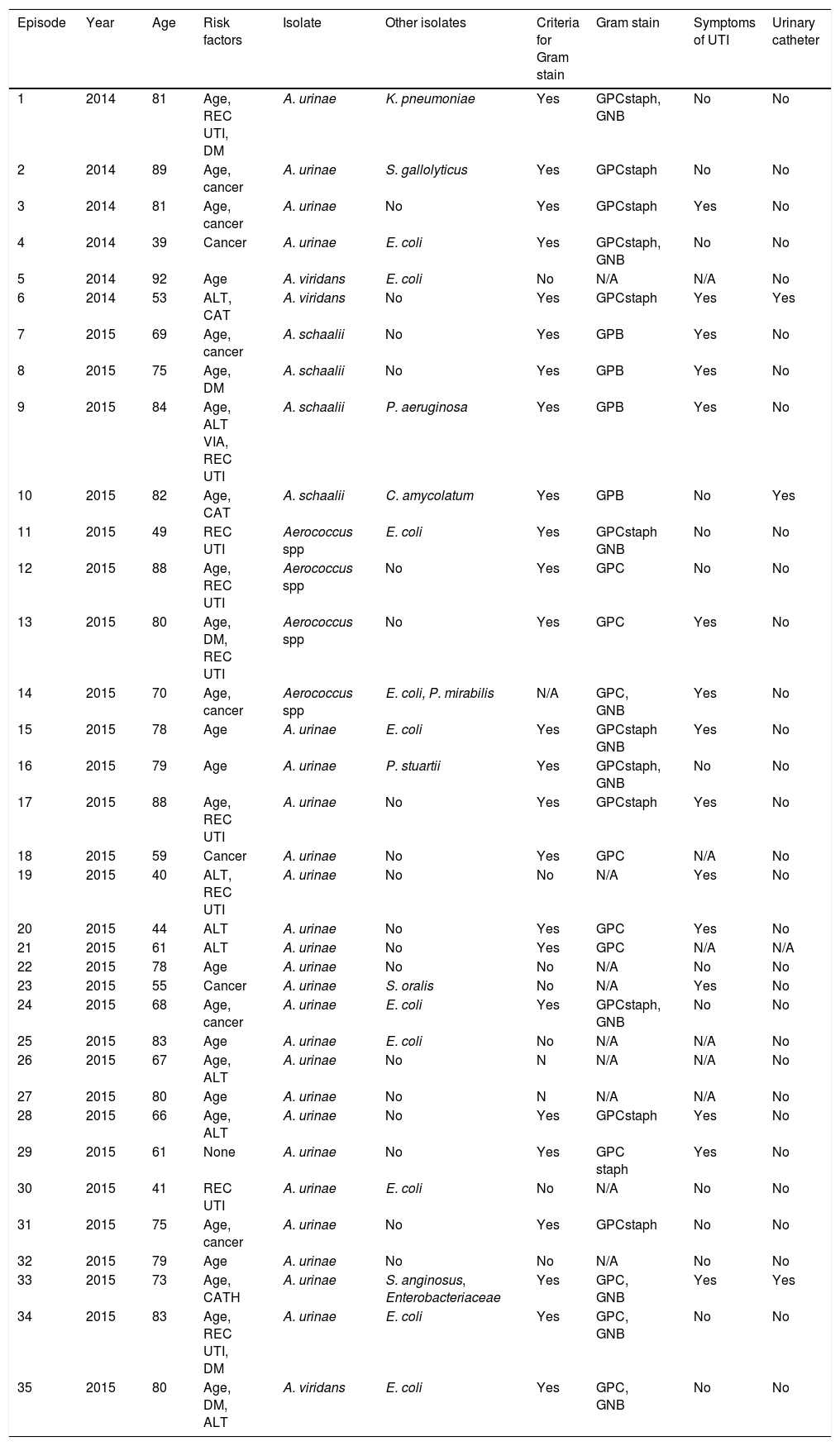

The study population was made up of 25 women and 9 men. The mean age was 75 years, ranging from 39 to 92 years. Patient demographic data for this cohort is shown in Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of pacients.

| Episode | Year | Age | Risk factors | Isolate | Other isolates | Criteria for Gram stain | Gram stain | Symptoms of UTI | Urinary catheter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2014 | 81 | Age, REC UTI, DM | A. urinae | K. pneumoniae | Yes | GPCstaph, GNB | No | No |

| 2 | 2014 | 89 | Age, cancer | A. urinae | S. gallolyticus | Yes | GPCstaph | No | No |

| 3 | 2014 | 81 | Age, cancer | A. urinae | No | Yes | GPCstaph | Yes | No |

| 4 | 2014 | 39 | Cancer | A. urinae | E. coli | Yes | GPCstaph, GNB | No | No |

| 5 | 2014 | 92 | Age | A. viridans | E. coli | No | N/A | N/A | No |

| 6 | 2014 | 53 | ALT, CAT | A. viridans | No | Yes | GPCstaph | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | 2015 | 69 | Age, cancer | A. schaalii | No | Yes | GPB | Yes | No |

| 8 | 2015 | 75 | Age, DM | A. schaalii | No | Yes | GPB | Yes | No |

| 9 | 2015 | 84 | Age, ALT VIA, REC UTI | A. schaalii | P. aeruginosa | Yes | GPB | Yes | No |

| 10 | 2015 | 82 | Age, CAT | A. schaalii | C. amycolatum | Yes | GPB | No | Yes |

| 11 | 2015 | 49 | REC UTI | Aerococcus spp | E. coli | Yes | GPCstaph GNB | No | No |

| 12 | 2015 | 88 | Age, REC UTI | Aerococcus spp | No | Yes | GPC | No | No |

| 13 | 2015 | 80 | Age, DM, REC UTI | Aerococcus spp | No | Yes | GPC | Yes | No |

| 14 | 2015 | 70 | Age, cancer | Aerococcus spp | E. coli, P. mirabilis | N/A | GPC, GNB | Yes | No |

| 15 | 2015 | 78 | Age | A. urinae | E. coli | Yes | GPCstaph GNB | Yes | No |

| 16 | 2015 | 79 | Age | A. urinae | P. stuartii | Yes | GPCstaph, GNB | No | No |

| 17 | 2015 | 88 | Age, REC UTI | A. urinae | No | Yes | GPCstaph | Yes | No |

| 18 | 2015 | 59 | Cancer | A. urinae | No | Yes | GPC | N/A | No |

| 19 | 2015 | 40 | ALT, REC UTI | A. urinae | No | No | N/A | Yes | No |

| 20 | 2015 | 44 | ALT | A. urinae | No | Yes | GPC | Yes | No |

| 21 | 2015 | 61 | ALT | A. urinae | No | Yes | GPC | N/A | N/A |

| 22 | 2015 | 78 | Age | A. urinae | No | No | N/A | No | No |

| 23 | 2015 | 55 | Cancer | A. urinae | S. oralis | No | N/A | Yes | No |

| 24 | 2015 | 68 | Age, cancer | A. urinae | E. coli | Yes | GPCstaph, GNB | No | No |

| 25 | 2015 | 83 | Age | A. urinae | E. coli | No | N/A | N/A | No |

| 26 | 2015 | 67 | Age, ALT | A. urinae | No | N | N/A | N/A | No |

| 27 | 2015 | 80 | Age | A. urinae | No | N | N/A | N/A | No |

| 28 | 2015 | 66 | Age, ALT | A. urinae | No | Yes | GPCstaph | Yes | No |

| 29 | 2015 | 61 | None | A. urinae | No | Yes | GPC staph | Yes | No |

| 30 | 2015 | 41 | REC UTI | A. urinae | E. coli | No | N/A | No | No |

| 31 | 2015 | 75 | Age, cancer | A. urinae | No | Yes | GPCstaph | No | No |

| 32 | 2015 | 79 | Age | A. urinae | No | No | N/A | No | No |

| 33 | 2015 | 73 | Age, CATH | A. urinae | S. anginosus, Enterobacteriaceae | Yes | GPC, GNB | Yes | Yes |

| 34 | 2015 | 83 | Age, REC UTI, DM | A. urinae | E. coli | Yes | GPC, GNB | No | No |

| 35 | 2015 | 80 | Age, DM, ALT | A. viridans | E. coli | Yes | GPC, GNB | No | No |

REC: recurrent UTI, DM: diabetes mellitus, ALT: urinary tract alteration, CATH: use of urinary catheter, GPC: Gram-positive cocci, GPCstaph: Gram-positive cocci staphylococcus-like, GNB: Gram-negative bacilli.

All the samples corresponding to the 35 episodes presented pathological sediment (only in 5 cases were counted <40leukocytes/μL, but in all those cases they were >500BAC/μL). Plate counting of colony-forming units was in 33 of 35 episodes over 100.000, in 2 cases from 10.000 to 50.000 and in 1 case from 1.000 to 10.000.

Gram stain was performed in 26 of 35 urine samples, observing in all the cases cocci or bacilli forms. Bacteria in study were isolated from selective plates and in 100% of the cases were consistent with the observed form in the Gram stain.

Out of 34 patients, 33 had at least one risk factor, including age >65 years (76% of the individuals), immunosuppression or cancer (26%), abnormality of the genitourinary tract or recurrent UTI (24%), diabetes (15%) or a catheterization (12%). In 18 of the 35 documented episodes infections were monomicrobial (only A. schaalii or Aerococcus spp were isolated); while in the remaining cases17 urine samples harbored in addition other common uropathogenic bacteria (Enterobacteriaceae in more than 75% of samples).

DiscussionThe current study focuses in UTIs because MALDI-TOF was firstly introduced in the urine culture section of the laboratory for routine identification. In reviewing the literature, UTIs are the most frequent infection reported caused by aerococci and A. schaalii, however A. schaalii has been associated with sepsis, osteomyelitis, endocarditis and Fournier's gangrene13–16 among other and Aerococcus spp has been described to also cause urosepsis, infective endocarditis and osteoarticular infection.9,17,18 This highlights the invasive potential of these microorganisms. Fimbrial genes coding for attachment pili, recently revealed through the study of the genome of A. schaalii, can intervene in the colonization.19

The ongoing introduction of MALDI-TOF in other areas of the microbiology laboratory of HUGTiP permitted to identify Aerococcus spp and A. schaalii from other samples than urine. In the period of study, Aerococcus spp was present in 2 blood cultures and A. schaalii was isolated from one blood culture and 3 collections in the groin area. This result suggests that this organism can be found as a commensal on skin, as other studies concluded.11 Respecting the sepsis, in one case Aerococcus spp was the only bacteria isolated from blood culture and urine and in the other 2 episodes another recognized pathogen such as E. coli was isolated both from blood and urine cultures.

Some authors5 suggest to perform Gram stain to urine samples when the sediment is considered pathological in order to culture urines onto selective media. According to them, our results show that in all the cases of A. schaalii or Aerococcus spp infection optimal conditions of growth were achieved after performing a Gram stain. Thus, no A. schaalii or aerococci were ignored in urines with pyuria, but neither a selective plate was cultured unjustifiably.

The increase in the frequency of A. schaalii or Aerococcus spp isolates from urine samples in our laboratory coincides with the introduction of MALDI-TOF MS in clinical practice for routine identification of causative agents of UTI. It seems possible that this was due to a lack on the database included on biochemical tests used before 2015, which did not permit to identify these organisms.4,6,7 Mass spectrometry technique and molecular-based methods are more accurate since they allow distinguishing species with similar characteristics.

As Vouga and Greug have described in a recent review,20 the improvement in diagnosis tools is one of the reasons that have lead to the discovery of previously underreported preexisting prokaryotes, not only pathogenic microbes but also beneficial or harmless bacteria. The authors add the increase of human exposure to organisms due to social and environmental changes, and the increased susceptibility of people and virulence of bacteria. Further, knowledge of the invasive capacity of these emerging prokaryotes has increased the interest of microbiologists to isolate them.

As announced previously, UTIs are the most common presentation of an Aerococcus spp or A. schaalii infection. Although all the episodes of isolation of these organisms form urine samples were accompanied by pathological sediment, only 15 patients presented obvious symptoms of urinary tract infection (e.g. dysuria, pollakyuria). It is important to remember, on one hand, that at advanced ages such as our cohort symptoms of UTI can be very non-specific (confusion, malaise). On the other hand, asymptomatic bacteriuria can be accompanied by pyuria in 90% of the elderly.21 Thus, clinicians have to assess the role of the isolate to decide whether or not to treat it.

In our study we found 17 monomicrobial urine samples, and 18 cultures with a classical uropathogen in addition to aerococci or A. schaalii. Monomicrobial cultures of gram-positive bacteria were deemed as responsible for infection with the exception of 2 cases of urinary catheterized-patients where the presence of the microorganism was interpreted as colonization and malfunction of the catheter.

More controversial is to assess a mixed culture with a classical pathogen. Since the literature recognizes the uropathogenic potential of these organisms, in our laboratory we did not underestimate the infective role of Aerococcus spp or A. schaalii, especially if they are found in the same proportion as the classical uropathogen. Nevertheless, some authors with similar results consider the other possibly associated bacteria a commensal and they fail to identify it.7

At least one risk factor is found in 33 about 34 patients, which reveal their opportunistic behavior. Advanced age is the most frequent risk factor in our cohort, coinciding to other studies.7,11,22,23 An explanation is that the humid environment generated by urinary incontinence in elderly patients facilitates the colonization for A. schaalii. Following a recent study24 a similar reasoning can be made for small children, who can likely harbor the bacteria as they have enuresis and wear diapers.

Suffering from recurrent UTI is another common risk factor found in patients with aerococci/A. schaalii urinary tract infection. Uncomplicated UTI caused by classical uropathogen are usually treated orally with fluoroquinolones (such as ciprofloxacin) or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, however both Aerococcus spp and A. schaalii are resistant to these antibiotics to a slightly different extent, hence they can outlast to infections. Furthermore, its tedious culture and identification can prolong the detection.

Urologic-related predisposing conditions are also associated to UTI by gram-positive bacteria.3 In some cases, isolating Aerococcus spp/A. schaalii from a patient suffering chronic UTI could serve as an indicator of an alteration of the urinary tract.

Summarizing, microbiologists have to suspect an Aerococcus spp/A. schaalii infection before an elderly patient undergoing persistent UTI together with leukocyturia and negative cultures, now that literature recognizes its potential disease-causing capacity. New diagnostic tools such as MALDI-TOF have permitted to identify emerging prokaryotes. The role of these bacteria in normal microbiota and the incidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria remain to be studied.

Formatting of funding sourcesThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestNone.