Editado por: Dr. Ramón Pujol Farriols, MD. Facultad de Medicina, Univeristat de Vic, España

Última actualización: Noviembre 2023

Más datosEste estudio se centra en mejorar las habilidades profesionales de los Coordinadores de Calidad (QC) en la atención primaria de salud (APS) en Kosovo. Los CC son responsables de la supervisión interna de la calidad de las instituciones públicas de APS, pero se desconocen sus competencias para la mejora de la calidad. El objetivo era mejorar las habilidades profesionales de los QC a través de una formación específica, con el objetivo de mejorar la calidad de la atención sanitaria.

MétodosEl estudio implicó determinar las características básicas de los QC, evaluar el conocimiento de los estándares de calidad antes y después de la capacitación mediante un cuestionario; impartir dos sesiones de formación; y evaluar el impacto de la capacitación en el cumplimiento organizacional de los estándares de calidad de la atención médica. Como estadísticos de prueba se utilizaron la media, el porcentaje, el valor P, el intervalo de confianza, la prueba t y el rmcor.

ResultadosHubo un aumento estadísticamente significativo en el conocimiento de los QC sobre los estándares de calidad antes (x̅=11.4, SD = 2.9) y después de la capacitación (x̅=23.4, SD = 8.3), p = 0.011, IC 95%[3.9728, 20.0272]. Antes de la capacitación, el cumplimiento de los estándares de calidad fue del 83,1% (x̅=26,6, DE = 3,4), mientras que después de la capacitación aumentó al 87,5% (x̅=28,0, DE = 3,9), y esta diferencia fue estadísticamente significativa p = 0,047., IC del 95% [0,0303; 28,268].

ConclusiónEl estudio destaca la necesidad de una formación continua relacionada con la calidad y de herramientas y recursos adecuados para mejorar y mantener la calidad en la APS. Se necesitan más investigaciones para evaluar el impacto del sexo y la edad y la posible redefinición del papel de los QC.

One of the challenges in improving primary healthcare (PHC) quality and population outcomes is the awareness of quality, its tools, and methods.1 Such awareness can be increased by setting quality care standards,2 establishing mechanisms for quality supervision, and implementing targeted training as an effective intervention to improve the quality of care.3 Training in PHC significantly increases awareness of healthcare quality by increasing general knowledge,4–6 individual competence and performance,7 data collection,4,8 and communication skills.8,9 Awareness of expected quality standards and identification of knowledge gaps are essential for quality improvement activities.

In the developing country of Kosovo, public organizations of PHC are governed by local administrative municipalities, embracing the family medicine concept and aiming to treat 80% of health conditions.10 PHC institutions are subject to internal and external quality supervision.11 Quality Coordinators (QCs) have functional authority over the organization's quality control and improvement12 and carry out internal quality supervision. The Health Inspectorate of the Ministry of Health (MoH), which assesses the application of basic quality standards for PHC institutions in Kosovo, performs external quality supervision13 of PHC institutions.

While the members of the Health Inspectorate apply predefined quality standards to evaluate PHC institutions, there needs to be additional evidence of essential QCs' competencies and capabilities to improve the quality of PHC in Kosovo by applying the same standards in all PHC institutions.

This research aimed to shed light on this issue by assessing QCs' competencies with the following objectives: to obtain basic demographic information on QCs, to assess QCs knowledge of basic quality standards, to build on the capacity of QCs to supervise quality through targeted training on quality standards, and to evaluate the impact of training on PHC institutions' adherence to quality standards by exploring whether there is a relationship between QCs' knowledge of quality standards and organizational adherence to the standards.

Materials and methodsStudy design and time frameThis quantitative, non-randomized intervention study focused on evaluating QCs' competencies to perform their work by measuring awareness of basic quality standards of healthcare and building upon their knowledge of the same.

Units of observation and observed characteristicsThere are 2 types of observation units: PHC institutions and individual QCs.

Out of 38 publicly funded Main Family Medicine Centres (MFMCs) in PHC, 10 were eliminated due to duality of governance – parallel, mutually exclusive health systems (governed independently by Kosovo and Serbia). Fourteen other MFMCs providing maternity services (deliveries) were also eliminated, to limit the research to strictly outpatient institutions. The remaining 14 MFMCs were compared for adherence to 38 basic quality standards of healthcare, as evaluated by the Health Inspectorate in June–August 2018.

The comparison was made between MFMCs serving similar population numbers, creating 7 MFMC pairs. From each pair, 1 MFMC was selected for the intervention group, based on the lower-ranking score, as assessed by the Health Inspectorate. Individual QCs from the MFMCs of the intervention group were then selected to participate in the intervention. Each QC in the corresponding seven MFMCs was the only QC within the MFMC. Their knowledge of the 38 basic quality standards of healthcare was assessed before and after the intervention.

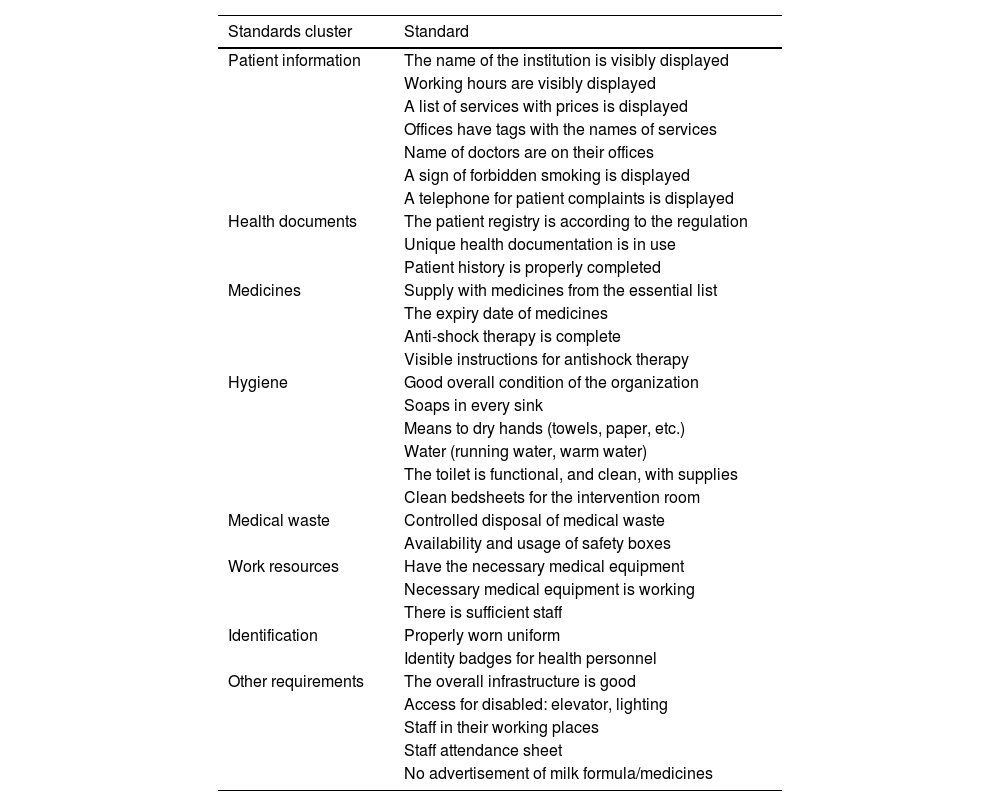

InterventionThe 7 selected QCs from the intervention group were invited for targeted training by the Health Inspectorate via an official memorandum. The training aimed to assess and build upon knowledge of QCs related to basic quality standards of healthcare based on which the PHC institutions where they serve were assessed for adherence by the Health Inspectorate. All of the invited QCs participated with no dropouts. Two training sessions were organized in official venues in the capital city of Prishtina: full-day training in December 2018 and a half-day follow-up in March 2019. The training included a summary of existing quality policies, particularly PHC policies, and related strategic developments; a detailed introduction of each of the standards used by the Health Inspectorate to evaluate healthcare organizations; the importance of the standards; their relation to legislative acts; how they are evaluated; and how they can be improved. Presenters were from the Health Inspectorate, Quality Division, Primary Healthcare Division, and Healthcare Services Directorate, all from the MoH. At the end of the training, QCs were provided with a copy of the standards for input in performing their organizational duties. The follow-up session was held 3 months later with the same participants. Pre- and post-training tests were administered to measure QCs' familiarity with the 32 standards used by the Health Inspectorate to evaluate their organization. For practical purposes of presenting the standards, they were grouped into 8 nominal clusters of different sizes that were categorically aligned by function and are presented in Table 1. The questionnaire required QCs to write all of the standards within the provided name of the cluster group.

Quality standards for primary healthcare institutions in Kosovo used by the Health Inspectorate of Kosovo.

| Standards cluster | Standard |

|---|---|

| Patient information | The name of the institution is visibly displayed |

| Working hours are visibly displayed | |

| A list of services with prices is displayed | |

| Offices have tags with the names of services | |

| Name of doctors are on their offices | |

| A sign of forbidden smoking is displayed | |

| A telephone for patient complaints is displayed | |

| Health documents | The patient registry is according to the regulation |

| Unique health documentation is in use | |

| Patient history is properly completed | |

| Medicines | Supply with medicines from the essential list |

| The expiry date of medicines | |

| Anti-shock therapy is complete | |

| Visible instructions for antishock therapy | |

| Hygiene | Good overall condition of the organization |

| Soaps in every sink | |

| Means to dry hands (towels, paper, etc.) | |

| Water (running water, warm water) | |

| The toilet is functional, and clean, with supplies | |

| Clean bedsheets for the intervention room | |

| Medical waste | Controlled disposal of medical waste |

| Availability and usage of safety boxes | |

| Work resources | Have the necessary medical equipment |

| Necessary medical equipment is working | |

| There is sufficient staff | |

| Identification | Properly worn uniform |

| Identity badges for health personnel | |

| Other requirements | The overall infrastructure is good |

| Access for disabled: elevator, lighting | |

| Staff in their working places | |

| Staff attendance sheet | |

| No advertisement of milk formula/medicines |

Data on the adherence of 14 MFMCs to basic quality standards of healthcare were collected during 2 rounds of inspection visits by the Health Inspectorate; initial inspections during June–August 2018 and final inspections during March–June 2019. During the initial inspections, closed-question questionnaires were distributed to the QCs, containing questions on QCs' demographic and work-related information (age, sex, education, healthcare worker profile, experience in healthcare, experience as a QC, and previous training).

Statistical analysesEvery recognized/completed standard was awarded 1 point, while the unrecognized/not completed standard was awarded 0 points. The observed outcome is the number of standards out of 32, observed in 2 different contexts, pre- and post-intervention, which are finally combined in a relationship analysis. In the case of observing OCs, it is “the number of standards known”, and in the case of observing PHC institutions, it is “the number of standards being adhered to”. In both cases, the total of standards, standard clusters, and individual standards were analyzed.

Statistical calculationsMicrosoft Excel 2020 was used to perform data analysis. The descriptive statistics measures calculated were mean, percentage, and standard deviation. Comparisons of the means within each of the trained QCs and PHC institutions, before and after training, were calculated via a two-tailed paired t-test. The significance was set to α=0.05, while the power was set to β=0.90. Repeated measures correlation (rmcorr) was used to determine the within-individual association of QCs knowledge and organizational adherence to standards pair, for the 2 measurements of each QC.

Ethical considerationsThe Board for Ethical Professional Supervision in the MoH approved the research under nr. 05–363/2017, while the participants signed consent forms before commencing the research. The confidentiality requirements were strictly observed throughout the study.

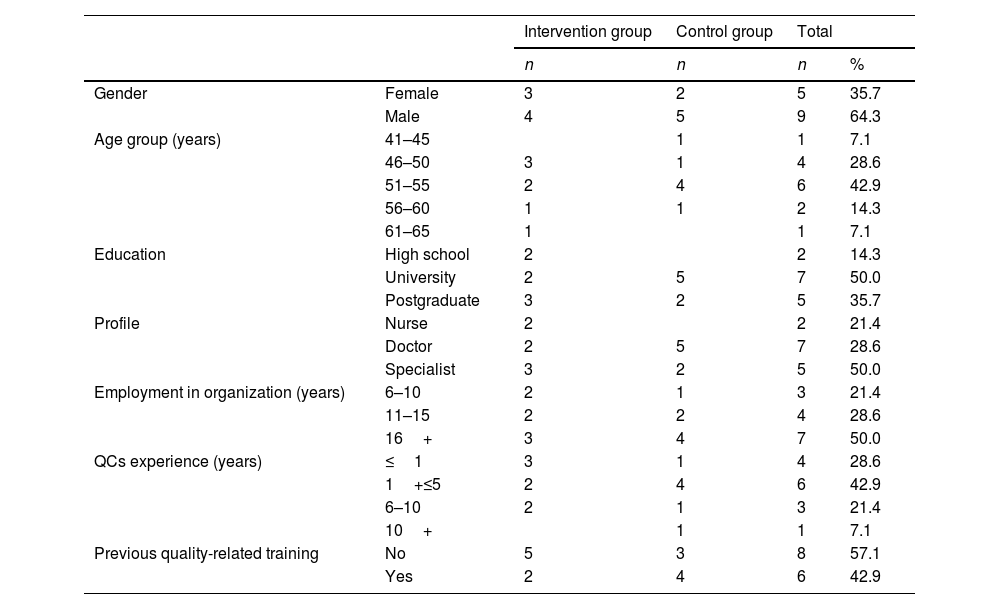

ResultsCharacteristics of the QCs of the PHC institutionsTable 2 presents the QCs demographic and work characteristics of the QCs population. As far as the intervention group, there were slightly more males than females; most of the QCs were in the 46–50 years age group; and only 2 QCs did not have a university education. Further, all QCs from the intervention group had served at least 6 years in their home organization, however, in most cases (n=3), the length of experience as a QC was 1 year or less. Most of the QCs from the intervention group (n=5) did not have previous quality-related training (Table 2).

Essential characteristics of the QCs of the PHC institutions (N=14).

| Intervention group | Control group | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | n | % | ||

| Gender | Female | 3 | 2 | 5 | 35.7 |

| Male | 4 | 5 | 9 | 64.3 | |

| Age group (years) | 41–45 | 1 | 1 | 7.1 | |

| 46–50 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 28.6 | |

| 51–55 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 42.9 | |

| 56–60 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 14.3 | |

| 61–65 | 1 | 1 | 7.1 | ||

| Education | High school | 2 | 2 | 14.3 | |

| University | 2 | 5 | 7 | 50.0 | |

| Postgraduate | 3 | 2 | 5 | 35.7 | |

| Profile | Nurse | 2 | 2 | 21.4 | |

| Doctor | 2 | 5 | 7 | 28.6 | |

| Specialist | 3 | 2 | 5 | 50.0 | |

| Employment in organization (years) | 6–10 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 21.4 |

| 11–15 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 28.6 | |

| 16+ | 3 | 4 | 7 | 50.0 | |

| QCs experience (years) | ≤1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 28.6 |

| 1+≤5 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 42.9 | |

| 6–10 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 21.4 | |

| 10+ | 1 | 1 | 7.1 | ||

| Previous quality-related training | No | 5 | 3 | 8 | 57.1 |

| Yes | 2 | 4 | 6 | 42.9 | |

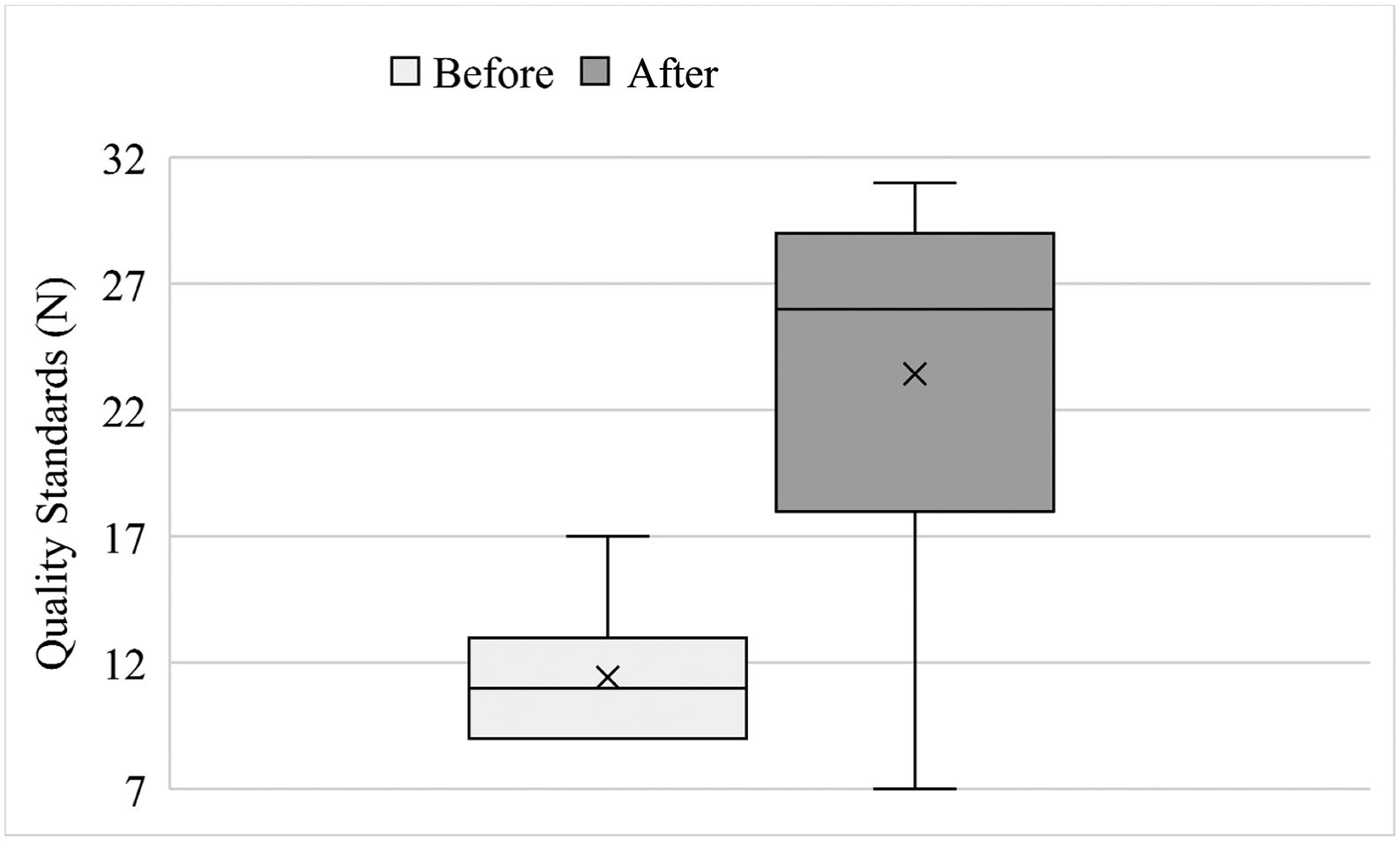

Before the training, QCs from the intervention group identified on average x̅=11.4 standards (SD=2.9) or 35.7% of them. The only standard that all QCs knew before the training was Patient history (Health documents cluster). Moreover, none of the QCs recognized a total of 9 or 28.1% of the standards: The display of the name of the institution (patient information cluster), complete anti-shock therapy with displayed instructions for it (medicines cluster), clean bedsheets (hygiene cluster), possession of necessary medical equipment, and functionality of the equipment (work resources cluster), infrastructure, staff presence list, and prohibition of advertising medicines/milk formulas in a healthcare organization (other cluster). The situation changed after the training; QCs were able to recognize on average x̅=23.4 (SD=8.3) standards or 73.2% of them. All the QCs from the trained group knew the following 3 standards: display of organizational working hours (patient information cluster), patient history (health documents cluster), and availability of soaps (hygiene cluster), while each standard was known by at least 3 QCs. A paired two-sample t-test was used to evaluate the impact of training on QC's knowledge of inspection standards. The results indicated a statistically significant increase in the QCs' knowledge of the standards before (x̅=11.4, SD=2.9) and after the training (x̅=23.4, SD=8.3), p=.011, 95% CI [3.9728, 20.0272], with a large effect size d=1.4 (Fig. 1).

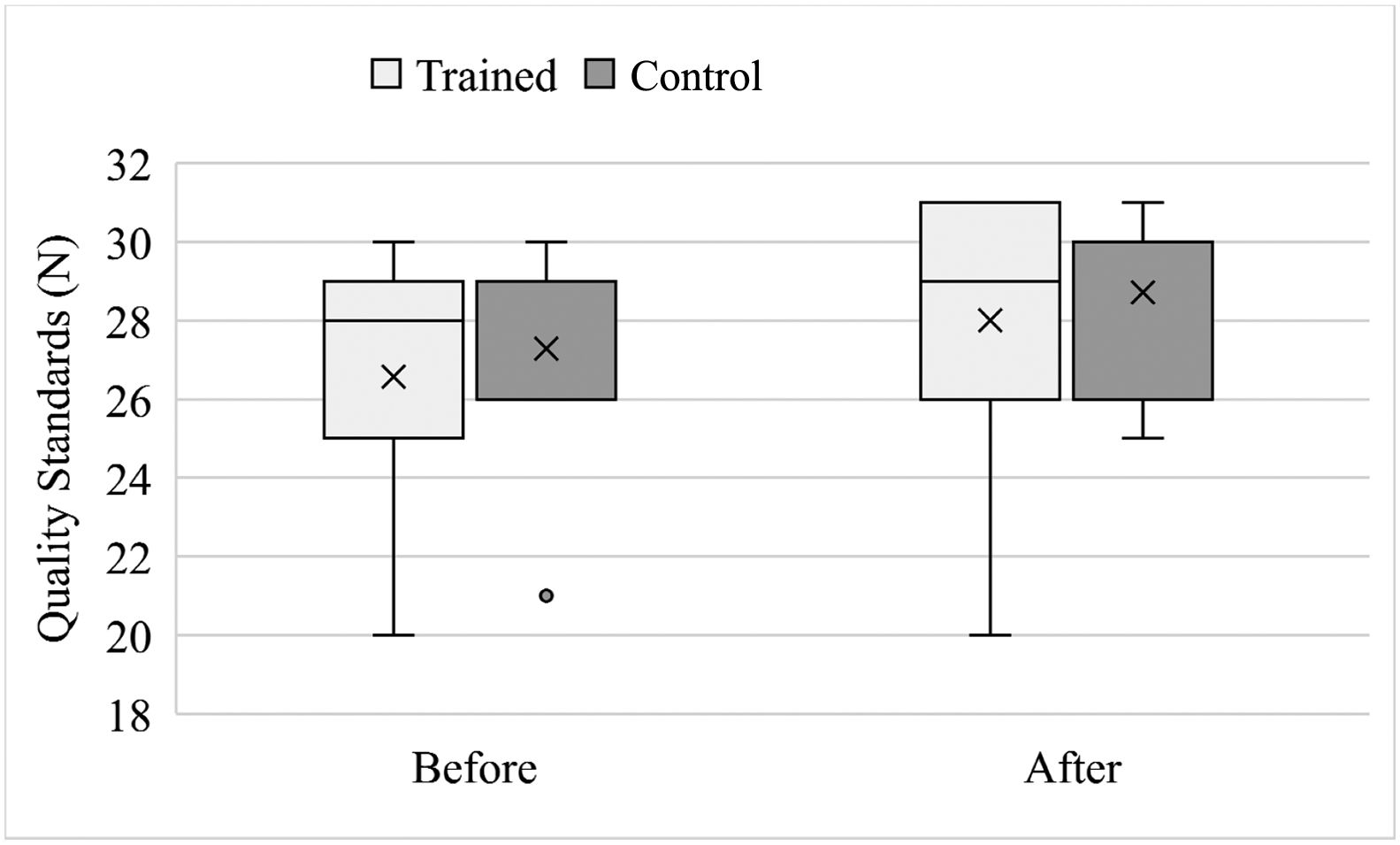

Analysis of organizational adherence to basic quality standards of healthcare before and after the QCs trainingFor the trained group, the respective PHC institutions adhered to 83.1% of the 32 standards before the training (x̅=26.6, SD=3.4). After the training, the adherence to standards increased to 87.5% (x̅=28.0, SD=3.9), and this difference was statistically significant, p=.047, 95% CI [0.0303, 2.8268], with a large effect size d=0.94. For the control group, before the training, the respective organizations adhered to 85.3% of the 32 standards (x̅=27.2, SD=3.1). After the training, the adherence to standards increased to 89.7% (x̅=28.7, SD=2.3), and this difference was statistically nonsignificant, p=.058, 95% CI [−0.0681, 2.9253], with a large effect size d=0.88 (Fig. 2).

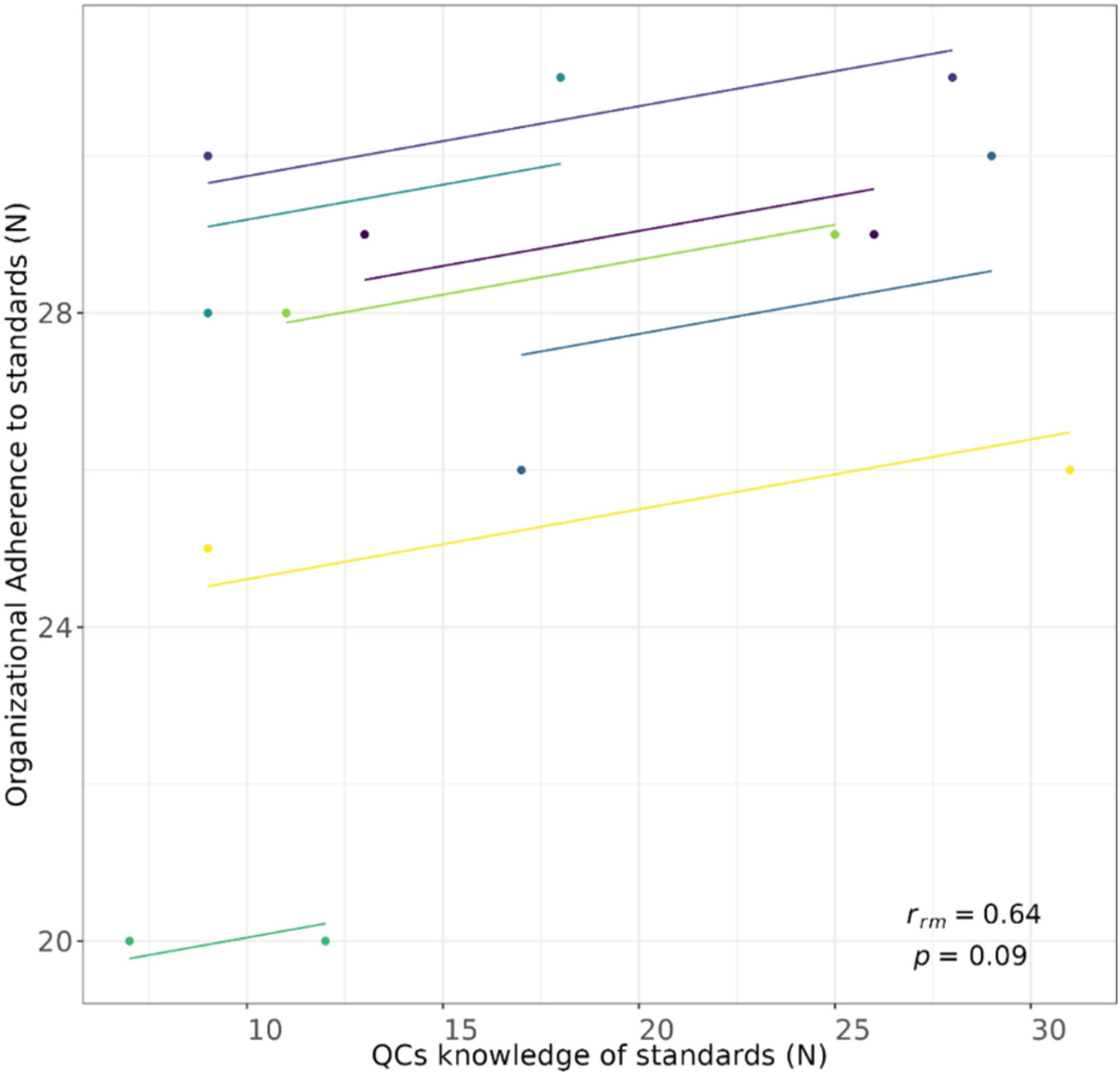

The relationship between QCs knowledge and organizational adherence to basic quality standards of healthcareThe repeated measures correlation test indicates that there is a stronger positive within-individual correlation for repeated measures of the “QCs knowledge – Organisational adherence to standards” pair, Rrm6=0.64, 95% CI [−0.113, 0.927], p=.085, even though with wide confidence intervals because there were only 14 data points (Fig. 3).

DiscussionThe findings reveal that in the intervention group, the QC's respondents had fairly low knowledge of basic quality standards although the adherence to standards within their organizations was fairly high. The targeted training significantly increased QCs' knowledge of quality standards by helping them identify previously overlooked standards, while the organizational adherence to the standards also increased after the QCs' training. A stronger positive relationship exists between QCs' knowledge and organizational adherence to standards. It is expected that training in healthcare quality increases participant knowledge; however, published studies have drawn diverse conclusions. In a study summarizing the experience of 10 years of training in healthcare quality, the authors found that knowledge, combined with mentorship and practice projects, has increased physicians' ability to analyze, study, and work on improving healthcare quality.14 Furthermore, a systematic review of 39 studies on teaching quality improvement to health personnel revealed that training improved knowledge and self-assurance but provided limited evidence on the impact of such improved knowledge on performance.15 This is unsurprising, as healthcare quality depends not only on health personnel knowledge and skills but also on the personal traits of the patients, healthcare organization, healthcare system, and broader environment.16 Similarly, in our study, although the knowledge of QCs was fairly low, the adherence to quality standards was greater, which suggests the existence of other drivers to increase quality.

This research will add new information on the demographic traits, professional skills, and needs of the personnel in charge of improving healthcare quality, thus guiding expectations and actions toward supporting them in performing such activities. In addition, this research provides basic evidence for informed decision-making regarding capacity building in PHC in the developing country of Kosovo. Finally, this novel study in Kosovo adds to the literature on the importance of training and capacity building in healthcare, as a basis for improving healthcare quality in developing countries.

This study has a few potential limitations. First, the sample size was small, which may have resulted in a type II error. However, the number of participants in this study was the maximum possible number for training, comparison, and evaluation in PHC outpatient organizations. Another limitation is the difficulty in replicating the study. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the only study on the fulfillment of basic quality standards of healthcare evaluated by external supervisors in the country. Therefore, it is challenging to compare the methodology or results with those of other studies locally. Additionally, comparison with the findings of other countries is complicated since different sets of quality standards are used for primary care in different countries, making it challenging to replicate the study.

On the other hand, this study boasts several crucial strengths. First, this study conclusively establishes a connection between external and internal supervision in healthcare, an area that has been grossly overlooked by researchers. Furthermore, the study uniquely examines the professional competencies of QCs. A comprehensive understanding of QCs' skills is paramount for improving healthcare quality, especially considering PHC's goal to cover 80% of health condition treatments. The research also highlights that targeted training, aligned with the same standards used to supervise and evaluate PHCs, can help QCs comprehend expected professional performance, thereby increasing organizational adherence to standards. Moreover, this research provides decision-makers with valuable new data to inform policy decisions on QCs appointments, regular training, and internal and external supervision of PHC. Finally, considering the limited quantitative data on the role of QC in Kosovo, this novel research becomes even more significant since there are no other comparable studies, to the best of the author's knowledge. Therefore, it can serve as a baseline for all other research studies in this area.

Policy and practice recommendations include the establishment of periodic mandatory quality-related training for QC staff and a shift of supervision focus from structural to process quality standards. Trained staff is instrumental in identifying and supporting quality improvement developments in PHC organization when the training is tailored to organizational and professional needs17; therefore, mandatory training should be provided for new QCs, followed by periodic follow-up training for already serving QCs. Furthermore, interestingly, QCs failed to recognize most of the structural standards used by the Health Inspectorate to evaluate the quality of their organizations; however, they considered other important quality issues, such as antibiotic prescription, patient confidentiality, and data archiving. This disparity raises the question of possible decoupling between what is relevant for quality assurers who aim to standardize healthcare and what is relevant for QCs – frontline healthcare workers who deal with the everyday practicalities of quality improvement. Therefore, there is a need to reopen discussions and reinitiate education for all staff at PHC centers about quality standards, tailoring the process to what is relevant for health personnel.18

Future research in the field may wish to explore the impact of other variables, such as QCs' gender and age as variables to determine whether differential behavioral effects may be observed, and multivariate statistical methods could be applied. More female QCs are needed since there are more female workers in PHC.19 Female professionals have a more person-centered, counseling, and compassionate communication style,20,21 which fosters active participation and joint decision-making,22 improving staff commitment to quality improvement actions. With the age of doctors in Kosova averaging 53 years,23 a new generation of younger QCs is essential to supplement these veterans, who may be in a position to teach younger candidates the intricacies and institutional histories vital for organizational success. Further, roles may need redefinition in a reformed system, and more nurses could be tapped to perform QC duties, empowering nurses to perform higher-level duties, and improving professional collaboration with doctors,18,24 shifting from instructional doctor–nurse relationships to complementary and supportive relationships. Finally, additional insight is needed to link increased QC knowledge and healthcare quality improvement, as QCs could play an essential role in communicating their knowledge to other professionals within the organization, acting as practice facilitators or coaches for quality improvement.25 Improved communication is crucial to improve the implementation of clinical guidelines,26,27 prevention in primary care,28,29 staff involvement in quality improvement activities, and acceptance of the change.25,30 Finally, one should remember the complexity of the research–policy–practice relationship therefore, in any chosen course of action, the 6 necessary elements ought to be followed: awareness on context and drivers, networking, evolving expectations with time, change, challenge and be challenged, and involving PHC practitioners.31

ConclusionsSimply appointing QCs does not guarantee improved job performance or quality in PHC in Kosovo. QCs are not fully equipped to promote quality at this level of healthcare. Targeted training can be a valuable tool for enhancing their knowledge of health inspection standards in PHC; however, QCs cannot work in isolation. It is necessary to invest in expanding the QC workforce by providing continuous and relevant training for QCs and other staff and ensuring the availability of appropriate tools and resources to assess, improve, and maintain quality. Additionally, a review and update of quality standards and other relevant policies are crucial. Such modifications can potentially lead to greater QCs effectiveness, and in the developing country of Kosovo, small changes may have a large impact on the quality of healthcare.

Funding disclosuresThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statementAll procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines, and have been approved by the Board for Ethical Professional Supervision in the Ministry of Health, nr. 05-363/2017. Informed consent was obtained from the participants, and the privacy rights of human subjects were observed.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Health Inspectorate, Quality Division, Primary Healthcare Division, and Healthcare Services Directorate from the Ministry of Health for their participation in the training.