Cancer diagnosis is unusual during pregnancy. It occurs in about 0.02–0.15% of all pregnancies, with an incidence of 1 case per 1000–1500 gestations.1 There is no real evidence of an increase due to pregnancy itself, and several authors point at the increased maternal age of the first pregnancy as the most important reason.2

The most common tumors diagnosed during pregnancy include breast cancer, lymphoma, leukemia and cervical cancer.3 Treatment during pregnancy should adhere as much as possible to standard care.4,5

It is a complicated situation as much in the diagnosis as in the following therapeutic plan, because of the impact of anti-neoplastic drugs on the embryo, fetus and long-term effects on children. Administration of cytotoxic drugs during the first trimester is particularly dangerous and it is not recommended. It is frequently associated with the development of malformations, embryo death and spontaneous abortion, as the organogenesis occurs in that moment.6

Even though chemotherapy can be administered relatively safe during second and third trimesters, risk for intrauterine grow retardation, low birth weight and transient myelosuppression exists.7,8 Premature delivery should be avoided and a full term delivery should be aimed for.2 Illness and mortality in newborn babies are directly related to gestational age at delivery.

Long-term studies after exposure to chemotherapy in utero reveal children with normal neurologic development and no increased health problems, although available data are limited.3,7 We want to contribute with our experience of two cases of fetal exposure to anti-neoplastic drugs.

First of all we present two in utero twins exposed to chemotherapy after maternal diagnosis of breast cancer. Woman aged 37 years with a spontaneous bicorial biamniotic gestation. This woman had been diagnosed of Hodgkin lymphoma when she was 24 years old and suffered a right mastectomy due to an invasive ductal carcinoma at the age of 32.

In the 20th week of gestation she is diagnosed of invasive ductal carcinoma grade 3 in the left mama, with IIIA stage (T3N1M0), triple negative tumor (RE-, RP-, HERZ-) and tested positive for a BRCA2 mutation. Treatment is started. She receives 5-fluorouracil 1000mg, epirubicin 150mg and cyclophosphamide 1000mg every 21 days, 4 cycles well-tolerated.

Normal prenatal ultrasound follow-up was performed, according to gestational age. Last cycle is administered at 31+6 gestational weeks and delivery is planned at 35+1 weeks by an elective cesarean.

Newborns do not require resuscitation. First twin weighs 2410g (p10–25) and presents asymptomatic early hypoglycemia controlled with enteral feeding. Second twin weighs 2250g (p10–25) and presents type II respiratory distress syndrome and requires nasal CPAP (FiO2 0.21) during its first 9h of life. After these pathologies, they remain asymptomatic with normal physical exploration and normal analytical parameters. They both receive formula feeding due to maternal treatment. Discharge occurs at 15 days of life (postmenstrual age 37+2 weeks) and subsequent follow-up. Both of them present normal growth (Table 1) and neurodevelopment at the age of 3, with no cardiological disorders.

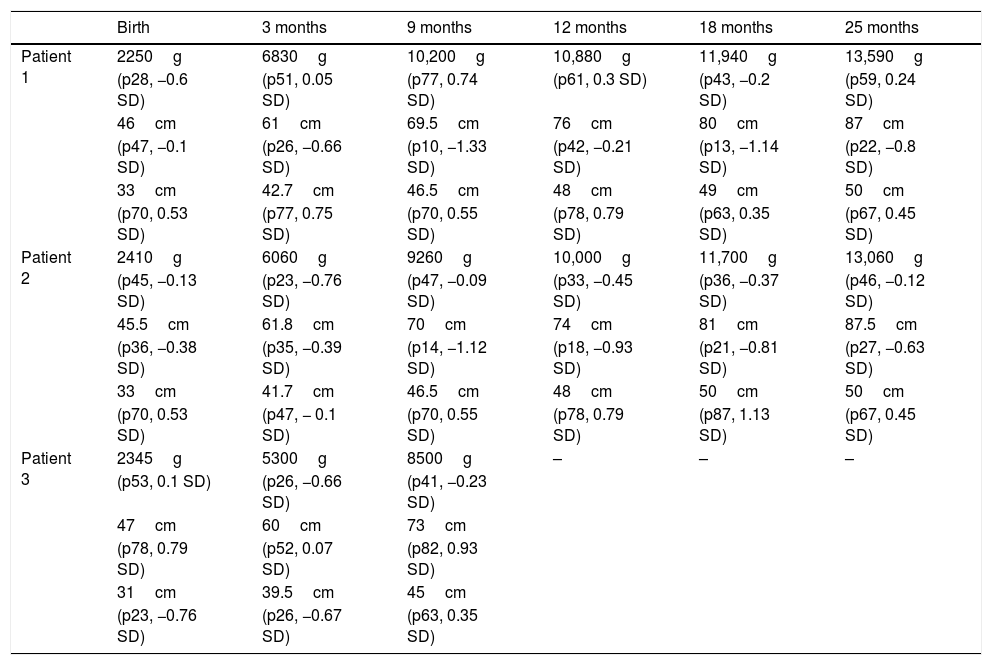

Patients growing follow-up.

| Birth | 3 months | 9 months | 12 months | 18 months | 25 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 2250g | 6830g | 10,200g | 10,880g | 11,940g | 13,590g |

| (p28, −0.6 SD) | (p51, 0.05 SD) | (p77, 0.74 SD) | (p61, 0.3 SD) | (p43, −0.2 SD) | (p59, 0.24 SD) | |

| 46cm | 61cm | 69.5cm | 76cm | 80cm | 87cm | |

| (p47, −0.1 SD) | (p26, −0.66 SD) | (p10, −1.33 SD) | (p42, −0.21 SD) | (p13, −1.14 SD) | (p22, −0.8 SD) | |

| 33cm | 42.7cm | 46.5cm | 48cm | 49cm | 50cm | |

| (p70, 0.53 SD) | (p77, 0.75 SD) | (p70, 0.55 SD) | (p78, 0.79 SD) | (p63, 0.35 SD) | (p67, 0.45 SD) | |

| Patient 2 | 2410g | 6060g | 9260g | 10,000g | 11,700g | 13,060g |

| (p45, −0.13 SD) | (p23, −0.76 SD) | (p47, −0.09 SD) | (p33, −0.45 SD) | (p36, −0.37 SD) | (p46, −0.12 SD) | |

| 45.5cm | 61.8cm | 70cm | 74cm | 81cm | 87.5cm | |

| (p36, −0.38 SD) | (p35, −0.39 SD) | (p14, −1.12 SD) | (p18, −0.93 SD) | (p21, −0.81 SD) | (p27, −0.63 SD) | |

| 33cm | 41.7cm | 46.5cm | 48cm | 50cm | 50cm | |

| (p70, 0.53 SD) | (p47, − 0.1 SD) | (p70, 0.55 SD) | (p78, 0.79 SD) | (p87, 1.13 SD) | (p67, 0.45 SD) | |

| Patient 3 | 2345g | 5300g | 8500g | – | – | – |

| (p53, 0.1 SD) | (p26, −0.66 SD) | (p41, −0.23 SD) | ||||

| 47cm | 60cm | 73cm | ||||

| (p78, 0.79 SD) | (p52, 0.07 SD) | (p82, 0.93 SD) | ||||

| 31cm | 39.5cm | 45cm | ||||

| (p23, −0.76 SD) | (p26, −0.67 SD) | (p63, 0.35 SD) |

Weight, height (evaluated according to Carrascosa et al., 2010 Spanish tables) and head circumference follow-up (evaluated according to Ferrández et al., 2002 Spanish table).

The second case report is about a 36-year-old woman who, in her 24th week of gestation, is diagnosed of acute promyelocytic leukemia, with an intermediate risk. In the 26th weeks, hematologists begin induction therapy with tetrionina 90mg/day during 35 days and idarubicin 23mg 4 days till complete remission at 32 weeks of gestation.

Normal prenatal ultrasound follow-up was performed, according to gestational age. Before the beginning of chemotherapy, the fetus had been diagnosed of unilateral severe renal hypoplasia. A programmed delivery was performed by cesarean section at 35 weeks of gestation, with no problems. The newborn weighs 2345g (p25–50) and presents hematomas in relation to extraction maneuvers, with no hematologic variations during admission (Table 2). The baby requires noninvasive ventilation with nasal CPAP (FiO2 0.28) during the first 72h of life, due to a type I respiratory distress syndrome, without further complications. An ultrasound examination was performed to diagnose a single kidney, which shows no other abnormalities. Discharge occurs at 11 days of life (postmenstrual age: 36+4 weeks), receiving formula feeding. Last control at 9 months of age shows normal growth (Table 1) and neurodevelopment.

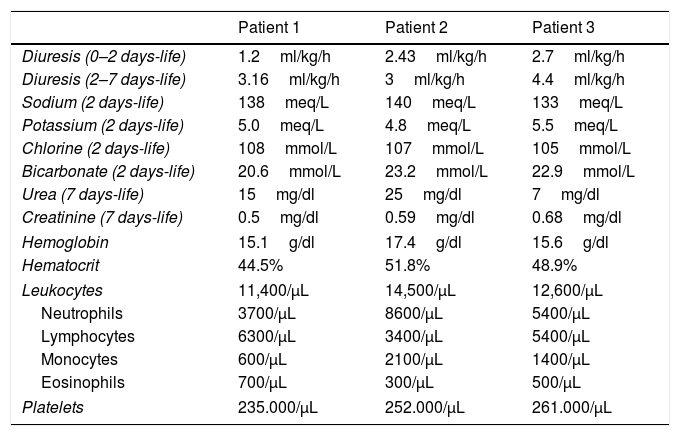

Kidney function and hematological evolution.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diuresis (0–2 days-life) | 1.2ml/kg/h | 2.43ml/kg/h | 2.7ml/kg/h |

| Diuresis (2–7 days-life) | 3.16ml/kg/h | 3ml/kg/h | 4.4ml/kg/h |

| Sodium (2 days-life) | 138meq/L | 140meq/L | 133meq/L |

| Potassium (2 days-life) | 5.0meq/L | 4.8meq/L | 5.5meq/L |

| Chlorine (2 days-life) | 108mmol/L | 107mmol/L | 105mmol/L |

| Bicarbonate (2 days-life) | 20.6mmol/L | 23.2mmol/L | 22.9mmol/L |

| Urea (7 days-life) | 15mg/dl | 25mg/dl | 7mg/dl |

| Creatinine (7 days-life) | 0.5mg/dl | 0.59mg/dl | 0.68mg/dl |

| Hemoglobin | 15.1g/dl | 17.4g/dl | 15.6g/dl |

| Hematocrit | 44.5% | 51.8% | 48.9% |

| Leukocytes | 11,400/μL | 14,500/μL | 12,600/μL |

| Neutrophils | 3700/μL | 8600/μL | 5400/μL |

| Lymphocytes | 6300/μL | 3400/μL | 5400/μL |

| Monocytes | 600/μL | 2100/μL | 1400/μL |

| Eosinophils | 700/μL | 300/μL | 500/μL |

| Platelets | 235.000/μL | 252.000/μL | 261.000/μL |

Kidney function evaluation and hematological control in the first week of life.

All of the three newborns conserved the urine output during their admission, and all the laboratory tests we did to evaluate the kidney function were normal according to their days of life (Table 2).

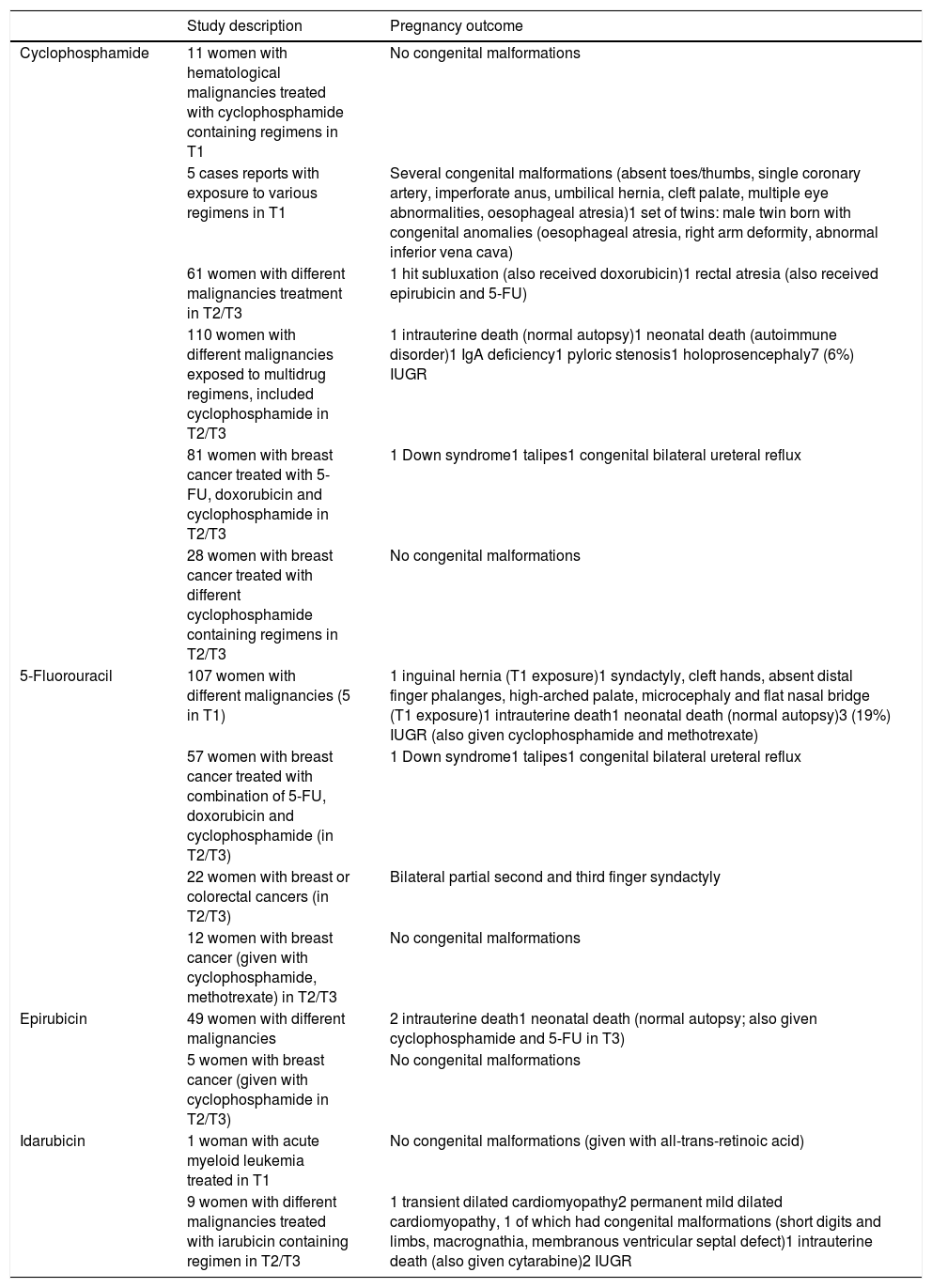

Cancer diagnosis during pregnancy should be made jointly by a multidisciplinary team (surgeon, hematologist, oncologist, obstetrician, neonatologist and psychologist).8 Exposure to chemotherapy during gestation, with the adequate drugs selection, seems to be safe and with no trend to indicate a higher rate of serious medical problems, nor cognitive impairment. Potential concerns may arise and will need to be followed, including pathologies as carcinogenesis, fertility problems, cardiac effects, neurological and psychological development7,10 (Table 3). Further investigations and prospective studies are important to guide optimal management of pregnant cancer patients and to provide parents and their children accurate information.

Summary of studies of women receiving same chemotherapic of our patients during pregnancy.9

| Study description | Pregnancy outcome | |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide | 11 women with hematological malignancies treated with cyclophosphamide containing regimens in T1 | No congenital malformations |

| 5 cases reports with exposure to various regimens in T1 | Several congenital malformations (absent toes/thumbs, single coronary artery, imperforate anus, umbilical hernia, cleft palate, multiple eye abnormalities, oesophageal atresia)1 set of twins: male twin born with congenital anomalies (oesophageal atresia, right arm deformity, abnormal inferior vena cava) | |

| 61 women with different malignancies treatment in T2/T3 | 1 hit subluxation (also received doxorubicin)1 rectal atresia (also received epirubicin and 5-FU) | |

| 110 women with different malignancies exposed to multidrug regimens, included cyclophosphamide in T2/T3 | 1 intrauterine death (normal autopsy)1 neonatal death (autoimmune disorder)1 IgA deficiency1 pyloric stenosis1 holoprosencephaly7 (6%) IUGR | |

| 81 women with breast cancer treated with 5-FU, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide in T2/T3 | 1 Down syndrome1 talipes1 congenital bilateral ureteral reflux | |

| 28 women with breast cancer treated with different cyclophosphamide containing regimens in T2/T3 | No congenital malformations | |

| 5-Fluorouracil | 107 women with different malignancies (5 in T1) | 1 inguinal hernia (T1 exposure)1 syndactyly, cleft hands, absent distal finger phalanges, high-arched palate, microcephaly and flat nasal bridge (T1 exposure)1 intrauterine death1 neonatal death (normal autopsy)3 (19%) IUGR (also given cyclophosphamide and methotrexate) |

| 57 women with breast cancer treated with combination of 5-FU, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (in T2/T3) | 1 Down syndrome1 talipes1 congenital bilateral ureteral reflux | |

| 22 women with breast or colorectal cancers (in T2/T3) | Bilateral partial second and third finger syndactyly | |

| 12 women with breast cancer (given with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate) in T2/T3 | No congenital malformations | |

| Epirubicin | 49 women with different malignancies | 2 intrauterine death1 neonatal death (normal autopsy; also given cyclophosphamide and 5-FU in T3) |

| 5 women with breast cancer (given with cyclophosphamide in T2/T3) | No congenital malformations | |

| Idarubicin | 1 woman with acute myeloid leukemia treated in T1 | No congenital malformations (given with all-trans-retinoic acid) |

| 9 women with different malignancies treated with iarubicin containing regimen in T2/T3 | 1 transient dilated cardiomyopathy2 permanent mild dilated cardiomyopathy, 1 of which had congenital malformations (short digits and limbs, macrognathia, membranous ventricular septal defect)1 intrauterine death (also given cytarabine)2 IUGR |

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Conflict of interestNo potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

It has not been published elsewhere and it has not been submitted simultaneously for publication elsewhere.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.