Lifestyle interventions (LSI) are recommended as first-line treatment for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), yet the strength of evidence underpinning LSIs effectiveness remains unclear. We systematically reviewed the literature on LSIs in PCOS, evaluated evidence quality and summarised recommendations for clinical practice.

Material and methodsWe searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL for all randomised trials evaluating any LSI in PCOS until April 2021. We extracted data on the LSIs’ characteristics, dietary composition, duration, implementation, compliance assessment, and reported outcomes. We evaluated the evidence gap using a network-map of evaluated interventions.

ResultsWe screened 550 citations and included 79 trials (n=4659 women). Most trials were from high-income countries (57/79, 72%) over a decade ago (48/79, 61%) and enrolled obese/overweight women (57/77, 74%). BMI was the commonest reported outcome (58/79, 73%), followed by weight (49/79, 62%), and testosterone (45/79, 57%). More than half of the trials had high-risk of randomisation (51/79, 65%) and allocation bias (49/79, 62%). Only 27 were registered prospectively (27/79, 34%). Two-thirds evaluated a dietary intervention (70/79, 88%), most commonly a hypocaloric diet (32/70, 46%); nineteen evaluated a combined dietary with pharmacological intervention (19/79, 24%), six combined diet with physical or behavioural intervention (6/79, 8%), and only one trial included all four elements.

ConclusionsEvidence on LSI in PCOS is of poor quality with high variations in trial design, comparisons, and outcome reporting. Hypocaloric diet is the most commonly recommended LSI intervention for primary care. Future trials are needed to evaluate pragmatic and simple LSIs in robust multicenter studies.

PROSPERO registrationCRD42020186571.

Las intervenciones en el estilo de vida (LSI) se recomiendan como tratamiento de primera línea para el síndrome de ovario poliquístico (SOP), sin embargo, la solidez de la evidencia que respalda la efectividad de la LSI sigue sin estar clara. Revisamos sistemáticamente la literatura sobre la LSI en el SOP, evaluamos la calidad de la evidencia, y resumimos las recomendaciones para la práctica clínica.

Material y métodosBuscamos en MEDLINE, Embase y CENTRAL, todos los ensayos aleatorios que evaluaran cualquier LSI en el SOP hasta abril de 2021. Extrajimos datos sobre las características, la composición dietética, la duración, la implementación, la evaluación del cumplimiento y los resultados informados de los LSI. Evaluamos la brecha de evidencia utilizando un mapa de red de intervenciones evaluadas.

ResultadosExaminamos 550 citas e incluimos 79 ensayos (n=4.659 mujeres). La mayoría de los ensayos se realizaron en países de ingresos altos (57/79, 72%), hace más de una década (48/79, 61%) e incluyeron mujeres obesas/con sobrepeso (57/77, 74%). El IMC fue el resultado informado con más frecuencia (58/79, 73%), seguido del peso (49/79, 62%) y la testosterona (45/79, 57%). Más de la mitad de los ensayos tuvieron alto riesgo de asignación al azar (51/79, 65%) y sesgo de asignación (49/79, 62%). Solo 27 se registraron de forma prospectiva (27/79, 34%). Dos tercios evaluaron una intervención dietética (70/79, 88%), más comúnmente una dieta hipocalórica (32/70, 46%); 19 evaluaron una dieta combinada con intervención farmacológica (19/79, 24%), 6 una dieta combinada con intervención física o conductual (6/79, 8%) y solo un ensayo incluyó los 4 elementos.

ConclusionesLa evidencia sobre la LSI en el SOP es de mala calidad con grandes variaciones en el diseño de los ensayos, las comparaciones y los informes de resultados. La dieta hipocalórica es la LSI más comúnmente recomendada para la atención primaria. Se necesitan ensayos futuros para evaluar la LSI pragmáticos y simples en estudios multicéntricos sólidos.

Registro PROSPEROCRD42020186571.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the commonest lifelong endocrine condition affecting women of reproductive age leading to chronic reproductive, metabolic, and physiological morbidity.1 PCOS often leads to delayed adverse clinical outcomes and poor mental health in affected women.1 Early management and effective prevention are essential to optimise the health of women with PCOS and reduce the risk of future complications such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, sleep apnoea and metabolic syndrome.2

Women with PCOS tend to have a higher body mass index (BMI) than the general population. As such, lifestyle interventions (LSI), including diet and exercise with or without behavioural intervention, are particularly helpful to aid weight loss and improve PCOS-related symptoms and complications.3,4 LSIs are recommended by most PCOS clinical guidelines as first-line interventions to optimise health in the community.5 However, the strength of the evidence on their effectiveness is purported to be inconsistent due to poor methodology and variations in outcomes reported.6 There remains no consensus on the optimal dietary or LSI that directly address the metabolic and endocrine features characteristic of PCOS.7 Methodological choices made by trialists may limit the implementation of LSI in the clinical care of women with PCOS such as reporting solely on biochemical or surrogate outcomes, evaluating single food items compared to a comprehensive dietary regime, not adjusting for participants’ compliance, and adopting a short follow-up leading to clinically irrelevant results.8 The features of the evidence need evaluation to explore the extent to which recommendations can be generated.

We aimed to systematically evaluate the current evidence on LSI in randomised trials on PCOS women to assess their methodological quality, define the current knowledge gap, guide clinical practice and assess future research need.

MethodsWe performed this systematic review using a prospectively registered protocol (CRD42020186571) and reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.9

Literature searchWe searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL for all randomised trials evaluating any LSI in women with PCOS from inception until April 2021. We used MeSH terms (syndrome, polycystic ovary, Stein-Leventhal, hyperandrogenism, hyperandrogenemia, lifestyle, healthy, diet*, food, nutrition, Exercises, Physical Activity, training, fitness, Woman, female, clinical trials, Randomi?ed) combining them using the Boolean operators AND/OR to screen for citations of relevant trials. No language restrictions or any other search filters will be applied. Complementary searches were conducted using Google Scholar and Scopus to identify additional relevant citations. We manually searched the bibliographies of potentially relevant articles to identify any missing citations.

Study inclusionTwo independent reviewers (BHA and NMH) completed the study selection and inclusion process in two stages. Initially, we screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant trials and then reviewed the full texts against our inclusion criteria. We included all randomised trials evaluating any LSI including dietary, exercise and behavioural interventions. Any discrepancies were resolved in consensus with a third reviewer (KSK). We excluded non-randomised studies, animal studies, and review articles. Trials that compared pharmacological interventions only with the same LSI introduced at baseline in both groups were excluded.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessmentBHA and NMH extracted data in duplicate using a piloted electronic data extraction tool. We assessed the characteristics of included trials reporting on the participant characteristics, inclusion/exclusion criteria, sample size, setting, compliance, and loss to follow-up rate. To evaluate current knowledge and future research need, we collected data on the design of included trials comprising the characteristics of evaluated LSI, their dietary composition, duration, and method of implementation. We also reported on the dietary assessment tools used to assess participants’ compliance and mapped out the reported outcomes.

BHA and NMH assessed the methodological quality of the included RCTs using the Cochrane risk of bias tool10 in duplicate. We evaluated each study in five domains: randomisation and sequence generation, adherence to assigned intervention groups, blinding and outcome assessment, completeness of outcome data, and selective outcome reporting.

Data synthesisWe reported our findings using percentages and natural frequencies. We evaluated the variation in sample size, dropout rate and methods and trial design to identify emerging themes and elements of best practice in the conduct of included randomised trials. We mapped out reported outcomes and compared them to the published core outcome set for trials on women with PCOS.11 We developed a network of comparators to evaluate the current knowledge gap and commonly evaluated interventions. We summarised recommendations to aid the adoption of LSI's in clinical practice following emerging trends in the reviewed evidence and recent evidence-based clinical practice guidelines.12 All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata, version 14 (StataCorp, TX).13

ResultsLiterature search, study characteristicsOur search identified 550 potentially relevant citations, of which we screened 157 in full and included 79 trials in our review (n=4659 women) (Fig. 1). Supplementary Table 1 summarises the characteristics of selected studies; the majority of included trials were relatively new published less than 10 years ago (48/79, 61%) and conducted in high-income countries (57/79, 72%). More than two-thirds included obese or overweight women with PCOS (57/77, 74%), 11 included women seeking fertility treatment (11/79, 14%), and only seven included adolescents (under 18s) with PCOS (8/79, 8.86%). The median sample size was 45 (range 6–343) and the median loss to follow-up was 14.8% (range 0–76.6%).

Characteristics of lifestyle interventionsThirty-one trials evaluated a pure dietary intervention (31/79, 39%), nineteen evaluated a combined dietary with pharmacological intervention (19/79, 24%), twelve had only a physical exercise intervention (12/79, 15%), six evaluated a combination of diet and physical exercise (6/79, 8%) or a combined dietary, physical and behavioural intervention (6/79, 8%). Four trials evaluated a combination of diet, physical and pharmacological intervention (4/79, 5%) and only one trial included all four elements14 (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1).

The most commonly evaluated dietary intervention was a generic hypocaloric diet (32/79, 40%), followed by a low-glycaemic diet (9/79, 11%) and low-carbohydrate diet (6/79, 8%) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). Majority of the trials implemented the intervention using one-to-one interviews with a dietician or researcher (19/79, 24%), five trials supplemented the intervention with group educational sessions on healthy eating habits to enforce the intervention (5/79, 6%). Three trials (3/79, 4%) provided only written information on how to adapt the intervention and change the participants’ lifestyle (e.g. using food item substitution list) (Supplementary Table 2).

About half of the included studied (34/79, 43%) employed some form of dietary assessment tools. These included using 24-hour recalls (4/34, 12%), 3-day food diaries (12/34, 35%), 7-day food diaries (7/34, 21%), food frequency questionnaires (5/34, 15%), unspecified food diaries (3/34, 8.8%) and three trials used more than one tool (Supplementary Table 2).

Most trials evaluating dietary and physical interventions included a 40–50min exercise session ranging from 3 to 5 sessions per week (Supplementary Table 3). The majority used aerobic or low-intensity exercises (18/40, 45%), eight used walking or self-resistance exercises (8/40, 20%), and 10 did not specify their mode of exercise (10/40, 25%). Only two studies used high intensity or endurance exercise programmes,15,16 and two used moderate-intensity exercises14,17 (Supplementary Table 3).

Among the trials that included a behavioural intervention, seven included general counselling sessions on lifestyle modification skills (7/17, 41%)18–23 and five implemented weekly counselling sessions to optimise dietary habits (5/17, 29%)14,16,24–26 (Supplementary Table 4). One trial provided a booklet on wellness, relaxation, and healthy lifestyle modification,27 two provided Structured lectures and flexible personal training on lifestyle modification skills23 and only three provided PCOS specific counselling25,26,28 (Supplementary Table 4).

Outcome reportingMajority of the trials focused on anthropometric and metabolic outcomes. The most commonly reported outcome in included trials was BMI (58/79, 73%), followed by weight (49/79, 62%), and Testosterone level (45/79, 57%). Serum lipids and glycaemic outcomes were reported in a third of included trials (Fig. 3). Only about 10% of trials reported on psychological outcomes (e.g. anxiety, depression, PCOSQ and HRQOL) with most focusing on objective biomarkers as surrogate clinical outcomes (Fig. 3).

Study quality and risk of biasThe overall quality was moderate with 51/79 (65%) of trials showing a high risk of bias for randomisation and 49/79 (62%) assignment to intervention groups (Fig. 4). Outcome assessment was poor in 31/79 studies (39%) and data loss was high in 37 studies (47%). Only a third were registered prospectively in an online trial registry (27/79, 34%) with an apparent high risk of selective outcome reporting in 51/79 (65%) (Fig. 4).

DiscussionSummary of findingsOur review identified an increasing number of trials highlighting the progressive interest in evaluating LSI as a first-line intervention for effective management of PCOS. Two-thirds of the trials were conducted within the last ten years which reflects the increased awareness for the benefits of adopting a healthy lifestyle to reduce the complications of PCOS as a chronic lifelong endocrine condition.29 However, we identified significant variations in the characteristics of the evaluated LSI and an overall poor trial methodology which could limit the synthesis of quality evidence. There were variations in the methods adopted to introduce the LSIs, monitor participant compliance, and reinforce lifestyle changes (Supplementary Table 2). Majority of the trials had a relatively small sample size with a high dropout rate (15%). As such, confidence in the available evidence remains poor30 and current recommendations on LSIs remain non-specific leading to poor permeation into clinical practice.

Strengths and limitationsThe strength of this review comes from its systematic design, comprehensive search strategy and pragmatic inclusion criteria to enable a holistic assessment of the evidence on LSI in PCOS. We extracted data in duplicate and adopted a standardised methodology supplemented with graphical tools to facilitate the interpretation of our findings and assess the current knowledge gap (Fig. 2).

Our findings were limited by the sub-optimal reporting in included studies. For example, only a third of included trials were registered prospectively and a minority published their protocols. Therefore, we were unable to gather detailed information on the intervention implementation methods, compliance assessment and outcome assessment tools. The reported follow up period in most included studies was limited (3–6 months) which also limits the generalisability of their findings into clinical practice. There was a wide variation in population characteristics, trial settings and intervention delivery methodology. Specifically, most trials described their evaluated dietary interventions using simple dietary composition formulas without providing an in-depth description of the implementation process of the evaluated LSIs or on the participants’ acceptability. Therefore, our analysis is largely descriptive and limited to the reported trials’ characteristics.

Recommendation for practiceLSIs are recommended as the first-line management strategy in women newly diagnosed with PCOS.5 However, there remains no consensus on the characteristics of the optimal LSI that directly addresses the pathophysiology of PCOS.31 Early adoption of effective LSIs in the community could help to reduce the long-term complications of PCOS.32 Furthermore, several behavioural strategies (e.g. peer-group support, education on problem-solving skills) could be introduced in primary care to increase LSIs uptake among affected women and minimise non-compliance.33

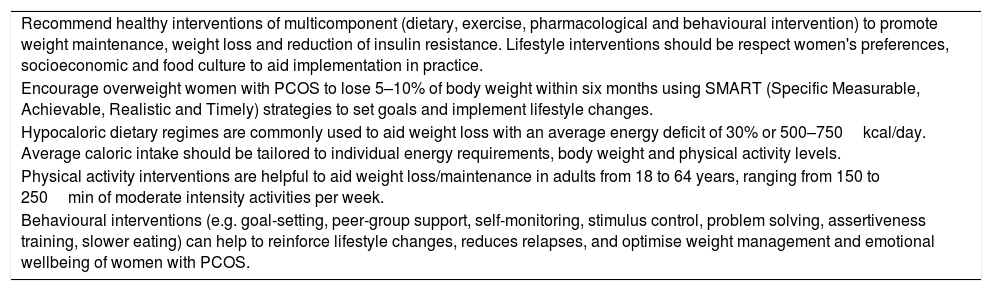

Our review highlights emerging patterns for effective adoption of LSIs in women with PCOS which are consistent with the recommendation of the recent international guideline on the diagnosis and management of PCOS6 (Table 1). Healthcare practitioners should promote the adoption of healthy multicomponent LSIs (combining dietary, exercise, pharmacological and behavioural interventions) to aid weight maintenance, weight loss and reduction of insulin resistance. These LSIs should be respectful of the women's preferences, socioeconomic and food culture to aid implementation in practice. Overweight women with PCOS should be encouraged to lose 5–10% of body weight within six months using SMART (Specific Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Timely) strategies. Behavioural interventions (e.g. goal-setting, peer-group support, self-monitoring, stimulus control, problem-solving, assertiveness training, slower eating) can help to reinforce lifestyle changes, reduces relapses, and optimise weight management and emotional wellbeing of women with PCOS.

Summary of recommendations for lifestyle interventions implementation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.

| Recommend healthy interventions of multicomponent (dietary, exercise, pharmacological and behavioural intervention) to promote weight maintenance, weight loss and reduction of insulin resistance. Lifestyle interventions should be respect women's preferences, socioeconomic and food culture to aid implementation in practice. |

| Encourage overweight women with PCOS to lose 5–10% of body weight within six months using SMART (Specific Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Timely) strategies to set goals and implement lifestyle changes. |

| Hypocaloric dietary regimes are commonly used to aid weight loss with an average energy deficit of 30% or 500–750kcal/day. Average caloric intake should be tailored to individual energy requirements, body weight and physical activity levels. |

| Physical activity interventions are helpful to aid weight loss/maintenance in adults from 18 to 64 years, ranging from 150 to 250min of moderate intensity activities per week. |

| Behavioural interventions (e.g. goal-setting, peer-group support, self-monitoring, stimulus control, problem solving, assertiveness training, slower eating) can help to reinforce lifestyle changes, reduces relapses, and optimise weight management and emotional wellbeing of women with PCOS. |

The most commonly evaluated dietary intervention in our review was a hypocaloric diet with an average energy deficit of 30% or 500–750kcal/day. Daily dietary needs should be tailored to individual energy requirements, body weight and physical activity levels. Lastly, promoting physical activity interventions could be helpful to aid weight loss/maintenance. On average, physical activity interventions should consist of 150–250min of moderate-intensity activities per week in adults from 18 to 64 years (Table 1).

Future research needIn the general population, the ideal LSIs for weight management should be safe, efficacious, nutritionally adequate, culturally acceptable, economically affordable to ensure long-term compliance and maintenance of weight loss.34 Contrastly, the majority of the LSIs evaluated in our review required participants to follow strict dietary formulas often imposing a significant change to their habitual diet and food shopping routine. Unsurprisingly, the dropout rate was relatively high in these RCTs which could indicate the difficulty in maintaining these LSIs on the long-term.35

High insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and blunted metabolism leading to inefficient use of energy sources and high conversion of glucose to fat are characteristic metabolic features of the polycystic ovary syndrome.36 As such, there is a need to identify and evaluate particular LSIs that can address this pathophysiology and facilitate the process of weight management in this cohort. Several studies showed that modest weight loss (as little as 5% of total body weight) in women with PCOS can induce short-term metabolic and reproductive health benefits.37 However, rapid loss using complex dietary interventions is commonly followed by gradual weight gain, poor compliance, high dropout rates ranging from 27 to 62%.34 Therefore, adopting simplified dietary modification aimed to gradually improve insulin resistance may produce greater benefits on the long-term in both obese and lean women with PCOS.

Engaging lay consumer in the process of LSI design and implementation is key to ensure participants’ long-term acceptability and compliance.38 This is particularly relevant when evaluating optimal methods to introduce the LSI with adequate peer or group support, to reinforce the intervention, and to equip the participants with problem-solving and critical thinking skills to optimise their lifestyle.38 Unfortunately, lay consumer engagement was largely absent in the evaluated trials in this review which could further explain the observed high dropout rate.39

We observed wide variations in the choice of outcomes reported in included trials as well as the outcome measurement tools used. This is likely to increase heterogeneity and reduce the quality of evidence synthesis leading to more research wastage.40 Using the proposed core outcome set for PCOS research11 could help to minimise this problem and improve the quality of evidence sought in future trials. Still, there remains no consensus on the optimal outcome measurement tools which is particularly relevant for biomarker essays (e.g. testosterone and anti-Müllerian hormone). Future consensus work is needed to optimise the quality of reporting in future trials evaluating LSIs in women with PCOS.11

ConclusionEvidence on LSI in PCOS is of poor quality with high variations in trial design, comparisons, and outcome reporting. Hypocaloric diet is the most commonly recommended LSI intervention for primary care. Future trials are needed to evaluate pragmatic and simple LSIs in robust multicenter studies.

Contribution to authorshipBHA conceived the idea, wrote the protocol and drafted the initial manuscript. BHA and NH conducted the search, extracted data and summarised the findings. KSK supervised study conducted and drafted the final manuscript.

FundingNo direct funding was provided to support this work. KSK is a Distinguished Investigator funded by the Beatriz Galindo (senor modality) Program grant given to the University of Granada by the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities of the Spanish Government.

Conflict of interestNone to declare.

None.