Obesity represents a major global health challenge. Female sexual dysfunctions have a negative impact on quality of life and overall health balance. A higher rate of female sexual dysfunctions in obese women has been suggested. This systematic review summarized the literature on female sexual dysfunction prevalence in obese women. The review was registered (Open Science Framework OSF.IO/7CG95) and a literature search without language restrictions was conducted in PubMed, Embase and Web of Science, from January 1990 to December 2021. Cross-sectional and intervention studies were included, the latter if they provided female sexual dysfunction rate data in obese women prior to the intervention. For inclusion, studies should have used the female sexual function index or its simplified version. Study quality was assessed to evaluate if female sexual function index was properly applied using six items. Rates of female sexual dysfunctions examining for differences between obese vs class III obese and high vs low quality subgroups were summarized. Random effects meta-analysis was performed, calculating 95% confidence intervals (CI) and examining heterogeneity with I2 statistic. Publication bias was evaluated with funnel plot. There were 15 relevant studies (1720 women participants in total with 153 obese and 1567 class III obese women). Of these, 8 (53.3%) studies complied with >4 quality items. Overall prevalence of female sexual dysfunctions was 62% (95% CI 55–68%; I2 85.5%). Among obese women the prevalence was 69% (95% CI 55–80%; I2 73.8%) vs 59% (95% CI 52–66%; I2 87.5%) among those class III obese (subgroup difference p=0.15). Among high quality studies the prevalence was 54% (95% CI 50–60%; I2 46.8%) vs 72% (95% CI 61–81%; I2 88.0%) among low quality studies (subgroup difference p=0.002). There was no funnel asymmetry. We interpreted that the rate of sexual dysfunctions is high in obese and class III obese women. Obesity should be regarded as a risk factor for female sexual dysfunctions.

La obesidad representa un importante desafío para la salud mundial. Las disfunciones sexuales femeninas tienen un impacto negativo en la calidad de vida y en el estado general de la salud. Se ha sugerido una mayor tasa de disfunciones sexuales femeninas en mujeres obesas. Esta revisión sistemática resumió la literatura sobre la prevalencia de las disfunciones sexuales femeninas en las mujeres obesas. Se registró la revisión (Open Science Framework OSF.IO/7CG95) y se realizó una búsqueda bibliográfica sin restricciones de idioma en PubMed, Embase y Web of Science, desde enero de 1990 hasta diciembre de 2021. Se incluyeron estudios transversales y de intervención, estos últimos solo si proporcionaron datos de tasa de disfunción sexual femenina en mujeres obesas antes de la intervención. Para la inclusión, los estudios debieron haber utilizado el índice de función sexual femenina o su versión simplificada. Se evaluó la calidad del estudio para determinar si el índice de función sexual femenina se aplicó correctamente utilizando seis ítems. Se resumieron las tasas de disfunciones sexuales femeninas examinando las diferencias entre obesas frente a obesas clase III y subgrupos de alta frente a baja calidad. Se realizó un metaanálisis de efectos aleatorios, se calcularon los intervalos de confianza (IC) del 95% y se examinó la heterogeneidad con la estadística I2. El sesgo de publicación se evaluó con un gráfico en embudo (funnel plot). Hubo 15 estudios relevantes (1.720 mujeres participantes en total, con 153 obesas, y 1.567 mujeres con obesidad claseIII). De estos, 8 (53,3%) estudios cumplieron con > 4 ítems de calidad. La prevalencia general de disfunciones sexuales femeninas fue del 62% (IC 95%: 55–68%; I2: 85,5%). En las mujeres obesas, la prevalencia fue del 69% (IC 95%: 55–80%; I2: 73,8%) frente al 59% (IC 95%: 52–66%; I2: 87,5%) en las obesas clase III (diferencia de subgrupos p=0,15). En los estudios de alta calidad, la prevalencia fue del 54% (IC 95%: 50–60%; I2: 46,8%) frente al 72% (IC 95%: 61–81%; I2: 88,0%) en los estudios de baja calidad (diferencia de subgrupos p=0,002). No hubo asimetría de embudo. Se interpretó que la tasa de disfunciónes sexuales es alta en mujeres obesas y obesas clase III. La obesidad debe ser considerada como un factor de riesgo para las disfunciones sexuales femeninas.

Sexual dysfunctions, a heterogeneous group of disorders that alter a person's ability to respond sexually or experience sexual pleasure, have a negative impact on self-esteem, often in couple relationships, as well as on the quality of life and overall health balance.1,2 The worldwide prevalence of female sexual dysfunctions (FSD) is estimated to be high.3 Obesity represents a major health challenge with a growing global prevalence.4,5

Key general health including cardiovascular and metabolic disease such as arterial hypertension6,7 and diabetes mellitus8,9 have been shown to be risk factors for FSD through systematic reviews and meta-analyses. There are several non-systematic reviews that suggest a higher FSD rate in obese women10–18 and some systematic reviews that show the recovery of female sexual functionality in class III obese women who undergo bariatric surgery.19–23 Unlike what happens with male sexual dysfunctions, the extent to which obesity and FSD are linked is not formally systematically reviewed. Given the gap identified above, we undertook a comprehensive and systematic review of studies that deployed formal instruments to evaluate the rate of FSD associated with obesity.

MethodsThe systematic review was registered (https://osf.io/7cg95) and reported following the PRISMA checklist.24

Search strategy and study selectionThrough the Community of Madrid Department of Health Virtual Library (Biblioteca Virtual de la Consejería de Sanidad de la Comunidad de Madrid), a systematic search for research25,26 was carried out with no language limitation in three electronic bibliographic databases from January 1990 to December 2021 including Pubmed, Embase, and Web of Science (WOS). The search term combination included keywords, free-text words and word variants based on the following concept: ((female sexual function index OR female sexual dysfunction) AND women) AND (overweight OR obesity). We limited our search to women of any age, excluding any studies that included only male participants. Supplementary electronic searches were conducted looking for other female sexual dysfunctions not captured by the above using the terms corresponding to vaginismus, low sexual desire, low libido, decreased libido, anorgasmia, arousal disorder, genital arousal, dyspareunia, sexual pain, sexual pain disorder, vaginal pain. Reference lists of the meta-analyses and systematic reviews found27,28,23,29,30 were examined for potentially relevant citations. All citations found were exported to Zotero, where duplicates were removed.

Two independent reviewers, a medical methodologist and a medical expert in sexology, reviewed the titles and abstracts of all the citations found. We excluded studies conducted in women with diabetes, metabolic syndrome, endometriosis, or urinary incontinence, as these are known to increase the risk of FSD.7,31–35 Studies in obese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) were also excluded, as there is some evidence of a relationship with risk of FSD.36–41 Studies that did not report the presence of FSD, or did not specify BMI, or did not include obese women, or did not distinguish between obese and non-obese women, were discarded. We only included studies reporting the rate of FSD, or at least one female sexual dysfunction in obese women, whether they were prevalence studies or obesity intervention studies reporting pre-intervention prevalence. After each reviewer independently applied these criteria, a third reviewer, a methodologist, arbitrated on the decision to accept or reject the studies in which there was disagreement. The reviewers who assessed the relevance of the studies for the present investigation knew the names of the authors, but not the institutions, nor the journal of publication, nor the results, when they applied the eligibility criteria.

Data extraction and study quality assessmentData were extracted and the quality of the selected studies assessed. The information extraction was recorded in Microsoft Excel, including the following parameters: Author, year, type of obesity, population, type of study, country, age range, number of women, FSD Definition, FSD prevalence (%), and female sexual function Index (FSFI) total score. The quality of the selected studies was based on the recommendations to facilitate the comparability of future studies that use the FSFI.42 There were 6 quality items. They covered the examination of all exclusion criteria for data sampling and analysis, especially whether or not sexually active women were excluded from the analysis, presentation of the means or medians and standard deviations or percentiles of all subscales and of the total score of the FSFI, and the use the cutoff point of Wiegel et al.43 for the detection of FSD (≤26.55 points). We regarded compliance with >4/6 items (>67%) to reflect good quality.

Data synthesisFrom the numerical data reported, we tabulated reported FSD rate of all the studies and FSFI total score where reported. We also tabulated study quality, age groups, menopausal status, and level of obesity, as factors related to FSDs. To investigate heterogeneity statistically, we examined for differences between obese vs class III obese and high vs low quality subgroups, calculated I2 statistic, and performed subgroup and meta-regression analysis. Overall meta-analysis using random effects model.44 We evaluated publication bias and small study effects using funnel plot of logit of prevalence vs its standard error. We used Stata software for statistical analysis.

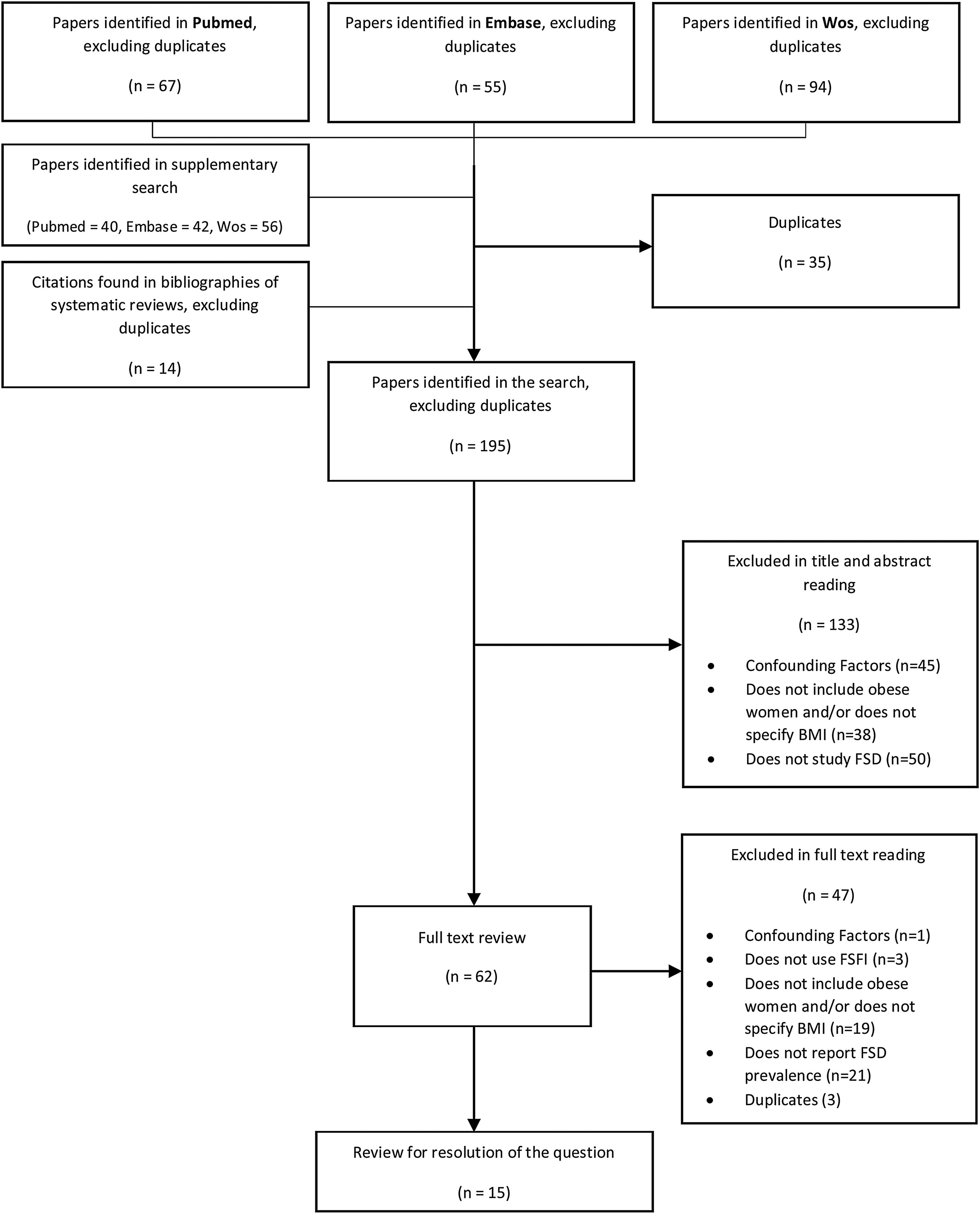

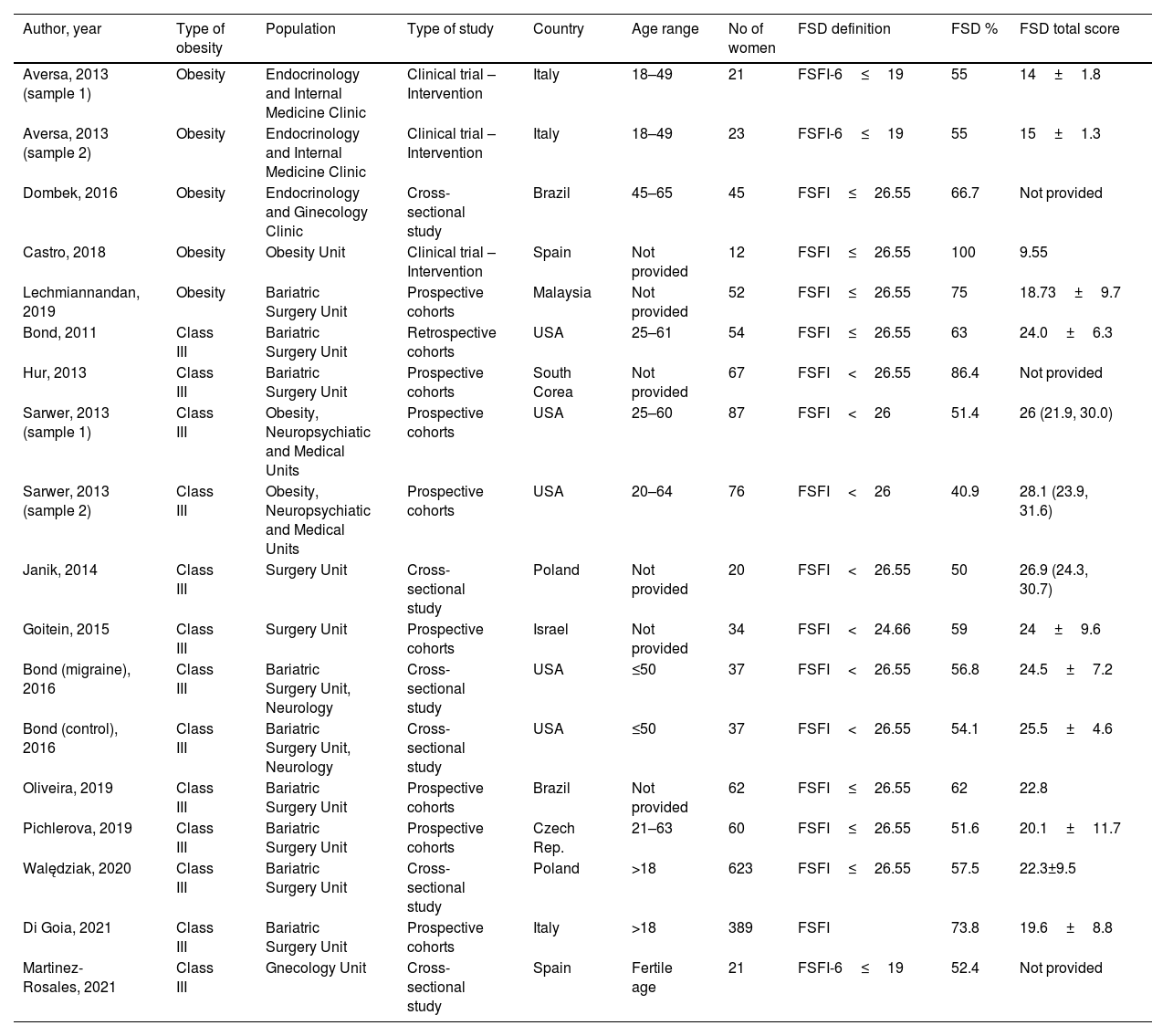

ResultsFig. 1 describes the process of the search, identification and selection of studies. A total of 195 studies were obtained. After reading the titles and abstracts, a total of 62 studies were examined in full text by pairs, and 15 studies were finally selected45–59 There was 100% agreement between reviewers regarding selection. There were 5 cross-sectional studies (one providing two rates),47 7 prospective cohort studies (one providing two rates),58 1 retrospective cohort study, and 2 clinical intervention trials (one providing two rates),46 which together included a total of 1720 women. The sample size ranged from 12 to 623 women, with a mean (standard deviation) of 95.5 (154.3) women and a median of 48.5. All the studies had as reference population people who attended specialized clinical units, of which 5 were medical units and 10 were surgical. The age groups of 11 of the 15 included adult women of any age with a lower age limit of 18 years, and an upper limit of indefinite or up to 64 years. Two studies focused on premenopausal women, setting an upper age limit of up to 50 years,46,47 one study focused on fertile age56 and another study focused on postmenopause,51 setting limits of 45–65 years. The investigations covered a wide geographical distribution: Europe (n=7), North America (n=3), Asia (n=3) and South America (n=2). The results of the studies are presented in Table 1.

Characteristics of the selected studies in the systematic review on prevalence of female sexual dysfunctions in obesity.

| Author, year | Type of obesity | Population | Type of study | Country | Age range | No of women | FSD definition | FSD % | FSD total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aversa, 2013 (sample 1) | Obesity | Endocrinology and Internal Medicine Clinic | Clinical trial – Intervention | Italy | 18–49 | 21 | FSFI-6≤19 | 55 | 14±1.8 |

| Aversa, 2013 (sample 2) | Obesity | Endocrinology and Internal Medicine Clinic | Clinical trial – Intervention | Italy | 18–49 | 23 | FSFI-6≤19 | 55 | 15±1.3 |

| Dombek, 2016 | Obesity | Endocrinology and Ginecology Clinic | Cross-sectional study | Brazil | 45–65 | 45 | FSFI≤26.55 | 66.7 | Not provided |

| Castro, 2018 | Obesity | Obesity Unit | Clinical trial – Intervention | Spain | Not provided | 12 | FSFI≤26.55 | 100 | 9.55 |

| Lechmiannandan, 2019 | Obesity | Bariatric Surgery Unit | Prospective cohorts | Malaysia | Not provided | 52 | FSFI≤26.55 | 75 | 18.73±9.7 |

| Bond, 2011 | Class III | Bariatric Surgery Unit | Retrospective cohorts | USA | 25–61 | 54 | FSFI≤26.55 | 63 | 24.0±6.3 |

| Hur, 2013 | Class III | Bariatric Surgery Unit | Prospective cohorts | South Corea | Not provided | 67 | FSFI<26.55 | 86.4 | Not provided |

| Sarwer, 2013 (sample 1) | Class III | Obesity, Neuropsychiatic and Medical Units | Prospective cohorts | USA | 25–60 | 87 | FSFI<26 | 51.4 | 26 (21.9, 30.0) |

| Sarwer, 2013 (sample 2) | Class III | Obesity, Neuropsychiatic and Medical Units | Prospective cohorts | USA | 20–64 | 76 | FSFI<26 | 40.9 | 28.1 (23.9, 31.6) |

| Janik, 2014 | Class III | Surgery Unit | Cross-sectional study | Poland | Not provided | 20 | FSFI<26.55 | 50 | 26.9 (24.3, 30.7) |

| Goitein, 2015 | Class III | Surgery Unit | Prospective cohorts | Israel | Not provided | 34 | FSFI<24.66 | 59 | 24±9.6 |

| Bond (migraine), 2016 | Class III | Bariatric Surgery Unit, Neurology | Cross-sectional study | USA | ≤50 | 37 | FSFI<26.55 | 56.8 | 24.5±7.2 |

| Bond (control), 2016 | Class III | Bariatric Surgery Unit, Neurology | Cross-sectional study | USA | ≤50 | 37 | FSFI<26.55 | 54.1 | 25.5±4.6 |

| Oliveira, 2019 | Class III | Bariatric Surgery Unit | Prospective cohorts | Brazil | Not provided | 62 | FSFI≤26.55 | 62 | 22.8 |

| Pichlerova, 2019 | Class III | Bariatric Surgery Unit | Prospective cohorts | Czech Rep. | 21–63 | 60 | FSFI≤26.55 | 51.6 | 20.1±11.7 |

| Walędziak, 2020 | Class III | Bariatric Surgery Unit | Cross-sectional study | Poland | >18 | 623 | FSFI≤26.55 | 57.5 | 22.3±9.5 |

| Di Goia, 2021 | Class III | Bariatric Surgery Unit | Prospective cohorts | Italy | >18 | 389 | FSFI | 73.8 | 19.6±8.8 |

| Martinez-Rosales, 2021 | Class III | Gnecology Unit | Cross-sectional study | Spain | Fertile age | 21 | FSFI-6≤19 | 52.4 | Not provided |

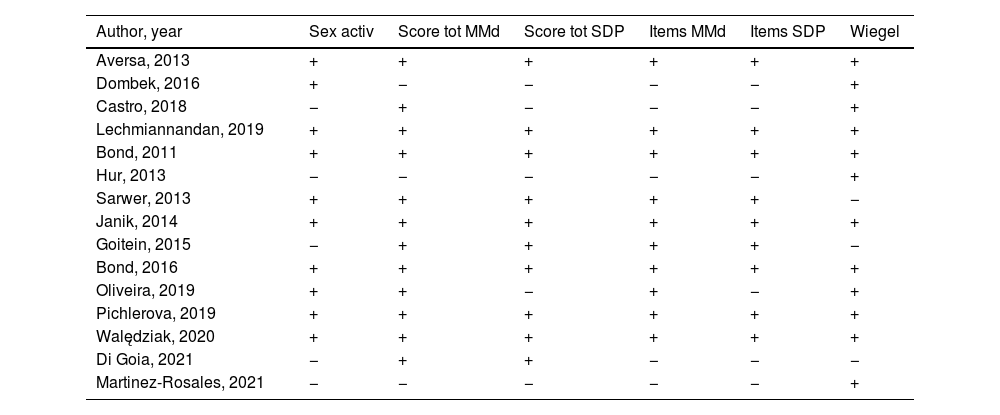

The quality of the included studies is summarized in Table 2. Of the total, 8 (53.3%) studies complied with >4 quality items. Only 5 studies49,50,52,53,56 did not report the condition of sexual activity as an inclusion criterion. The majority, 12 studies,45,52,54,55,57–59 reported the mean or median of the total score of the FSFI, and of these, all except two,49,57 also reported its standard deviation or percentiles. Regarding the subscales or items of the FSFI, 10 studies45–48,52,54,55,57–59 reported the mean or median of the total score of each subscale, and all but one57 also reported the standard deviation or percentiles of each item. Full version of FSFI was used in 13 and its simplified version (FSFI-6) in 2.46,56 Twelve of them45–49,51,53–57,59 used the pre-established and statistically validated cut-off point to detect the presence of FSD43: 26.55 points for the FSFI and 19 for the FSFI-6. Only Sarwer et al.58 and that of Goitein et al.52 used a different scale: 26 and 24.66 points respectively. Di Goia et al.50 did not report the cut-off point used. The average total score obtained in the FSFI or FSFI-6 (Table 1), was included in 12 of the 15 selected papers, with a range of values between 9.55 and 28.1 points for the FSFI, and it was lower than the cut-off point established for the detection of FSD in 10 of these 12 studies, with the exception of the studies by Sarwer et al.58 (26 and 28.1 respectively in each sample) and Janik et al.54 (26.9), the same ones whose prevalence of FSD was not higher than 50%.

Summary of the quality of the studies included in the systematic review on prevalence of female sexual dysfunctions in obesity.

| Author, year | Sex activ | Score tot MMd | Score tot SDP | Items MMd | Items SDP | Wiegel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aversa, 2013 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Dombek, 2016 | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| Castro, 2018 | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Lechmiannandan, 2019 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Bond, 2011 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hur, 2013 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Sarwer, 2013 | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Janik, 2014 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Goitein, 2015 | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| Bond, 2016 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Oliveira, 2019 | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Pichlerova, 2019 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Walędziak, 2020 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Di Goia, 2021 | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Martinez-Rosales, 2021 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

Sex Activ: presents as inclusion criteria the condition of sexually active woman, Score tot MMd: presents the result of the mean or median of the total score of the FSFI, Score tot SDP: presents the result of the standard deviation of the mean or percentiles of the median of the FSFI, Items MMd: presents the result of the total score of the mean or median of the subscales (items) of the FSFI, Items SDP: presents standard deviation or percentile results of the subscales (items) of the FSFI, Wiegel: uses a cut-off point of 26.55 points to detect DSF.

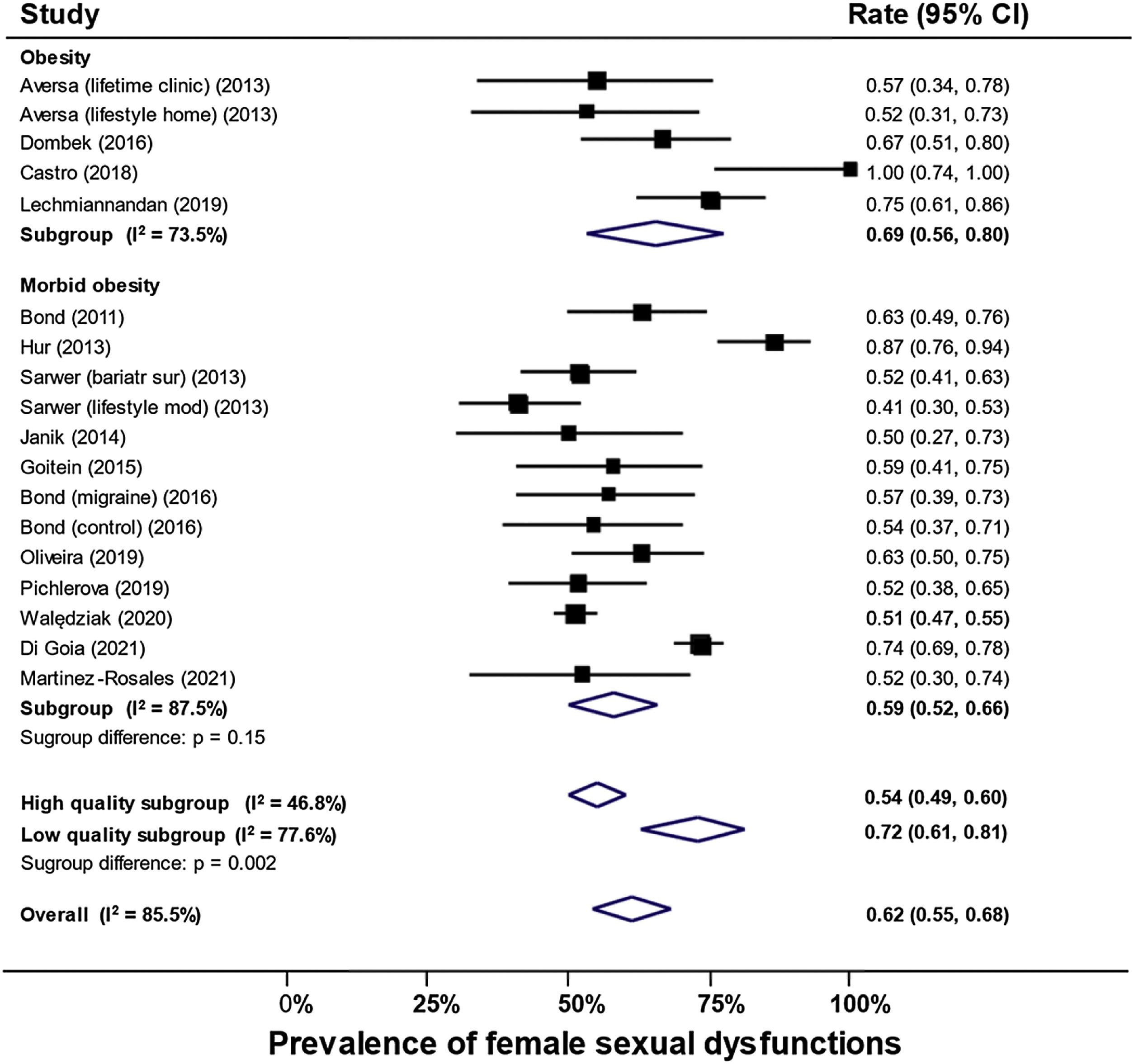

The FSD prevalence ranged from 51.4% to 100% across all studies. Some studies provided rates for more than sample and in total there were 18 samples for statistical synthesis. In one of the samples of the study by Sarwer et al.58 rate was 40.9% and the studies by Janik et al.54 (50%), both in women with class III obesity and with a lower number of participants compared to the rest of the studies reviewed. The four studies carried out in women with any kind of obesity (not only class III) had values above 50% in a range of 55–100% of prevalence of FSD. Among obese women the median rate of female sexual dysfunctions was 66.7% (range 55–100%, n=5), and among class III obese women it was 56.8% (range 40.9–86.4%, n=13).

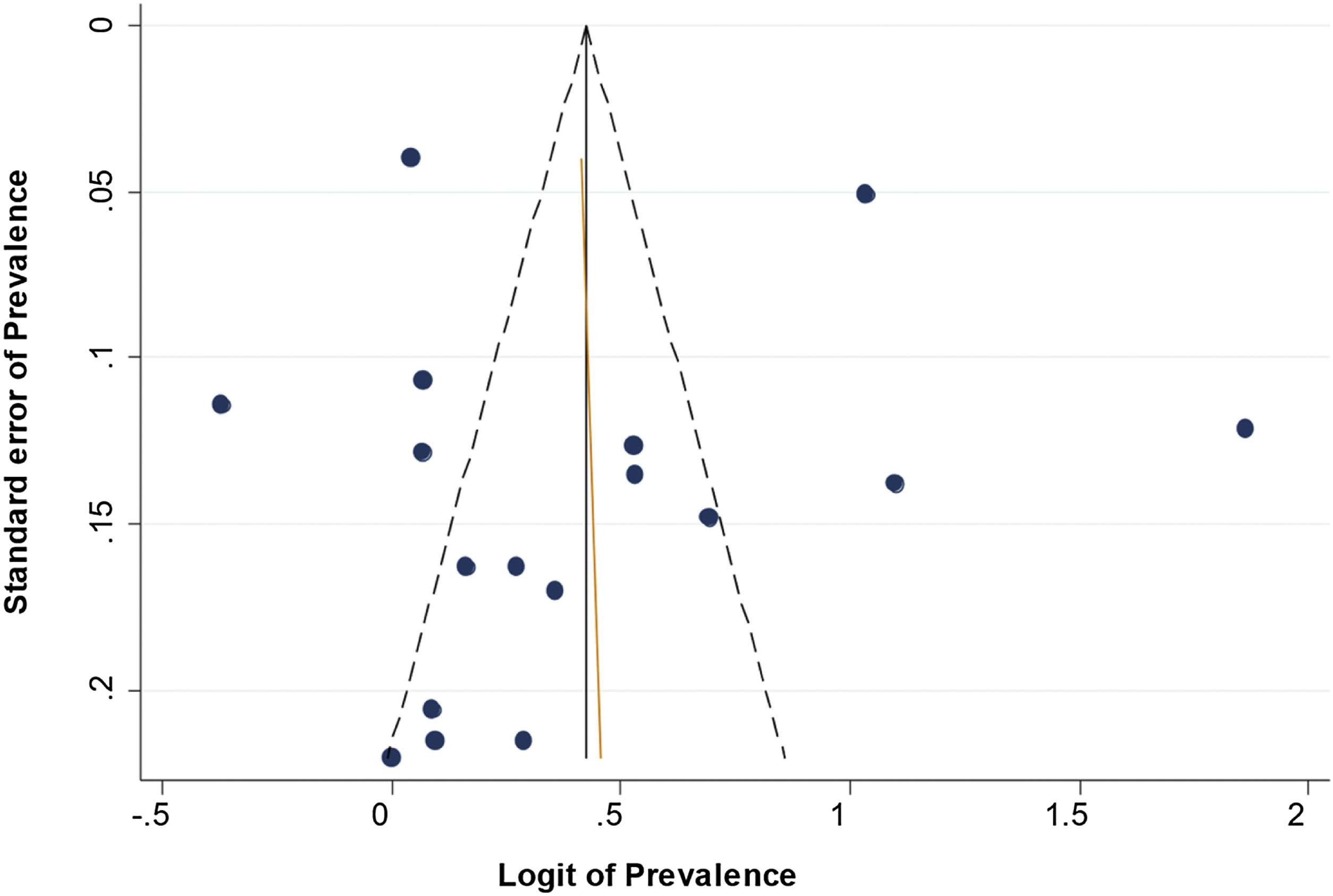

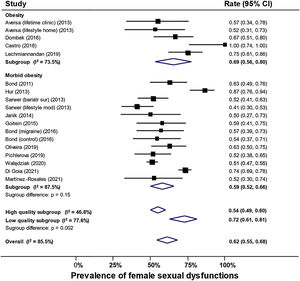

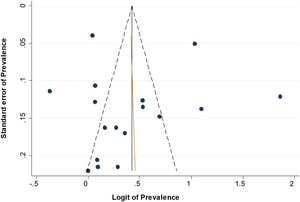

As shown in Fig. 2, there was no significant difference between the obese and class III obese subgroups (p=0.15). Overall prevalence of female sexual dysfunctions was 62% (95% CI 55–68%; I2 85.5%). Among obese women the prevalence was 69% (95% CI 55–80%; I2 73.8%) vs 59% (95% CI 52–66%; I2 87.5%) among those class III obese (subgroup difference p=0.15). Among high quality studies the prevalence was 54% (95% CI 50–60%; I2 46.8%) vs 72% (95% CI 61–81%; I2 88.0%) among low quality studies (subgroup difference p=0.002). Meta-regression confirmed FSFI was highly correlated with prevalence (p=0.001). It also showed that age and obesity levels (p=0.79 and 0.16 respectively) were not associated with prevalence but study quality was (p=0.001). There was no funnel asymmetry (Fig. 3).

Our systematic review, where over half of the studies had good quality, found that over two-thirds of obese women suffered FSD while over half of those with class III obesity suffered FSD. FSD prevalence exceeded 50% in all but two small studies among class III obese women. We found heterogeneity that could not be explained by difference in level of age and obesity, but it was related to study quality. The observed prevalence rates in obese women were above the estimated worldwide FSD prevalence for any age group.3

We did not find any systematic review that studies the prevalence of FSD in obese women, and in the very limited number of studies that study FSD prevalence in general population, very few record the body mass index (BMI). The prevalence of FSD in the samples analyzed was higher than that established by the ICSM worldwide and regardless of age (40–50%).3 Based on the results of our review, we recommend carrying out new studies on the prevalence of FSD in which BMI is recorded in order to determine and compare the rate of obese and not obese women with FSD in the community setting. Also, based on these advantages and disadvantages of the FSFI and in order to improve the accuracy and quality of future studies on the epidemiology of DSF, we propose the use of the FSM-2 questionnaire, a questionnaire validated in spanish60 which presents several advantages compared to the FSFI, because in addition to exploring all the phases of the female sexual response (desire, arousal, orgasm, satisfaction), it is more adapted to the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-V, it allows to know key aspects of sexual activity (sexual performance anxiety, initiative, confidence to communicate preferences, etc.) and contains fewer items.

We can conclude that obesity may be regarded a risk factor for FSD, as there is a very high prevalence of FSD in obese and class III obese women.

We conducted the review with a broad, comprehensive search. Even though the number of selected papers was small and the ranges of prevalence rates wide, the meta-analysis produced precise confidence intervals. Since the data presented for analysis were prevalences -in cross-sectional studies- or the prevalences before the study, we preferred to use FSFI42 over other quality tools such as the JBI checklist because the former is specifically developed for comparison between studies and assessment of the quality of the information provided by the FSFI, and thus it was not relevant to assess the overall quality of the studies. One of the main limitations of this systematic review is the high level of heterogeneity, which remained unexplained despite subgroup comparison. It is likely that this type of heterogeneity is unavoidable in prevalence reviews. Another criticism may be that there is a type of selection bias in that the samples were derived from clinical care units where women attended due to their obesity. However, this is a limitation of the published literature, not of our systematic review methodology. Our selection criteria were guided by scientific reasoning26 to exclude literature potentially biased by co-morbidities related to obesity. Fig. 1 illustrates transparently the amount of research excluded with the reasons for exclusion stated. The selection criterion requiring the use the FSFI, either full version or simplified, to detect the presence of FSD added quality to our review with respect to measurement. Despite limitations,42 FSFI is a widely used validated tool to detect FSD and it evaluates the relevant domains including desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain related to vaginal penetration.43 The FSFI-6 questionnaire, the simplified and validated version of the FSFI,61 has similar characteristics. Given the established measurement properties of FSFI, we can conclude that obesity is a risk factor for FSD confidently based on the high prevalence observed in our review.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest.

KSK is Distinguished Investigator at University of Granada funded by the Beatriz Galindo (senior modality) Program of the Spanish Ministry of Education.