Psychotropic medicines use alters according to socio-economic factors and perceived stress. The study aimed to assess the prevalence of use of psychotropic medicines and supplements (PMS) without medical advice, including storage at home, and its relationship with socio-demographic characteristics and perceived stress in primary care patients.

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional sample of adult attendees in an urban primary care unit in Crete, Greece, were surveyed during regularly scheduled appointments during a three-week period in October 2020. A questionnaire was distributed to investigate PMS use during the last 12 months. The validated Greek version of Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) was adopted to measure perceived stress.

ResultsOf 263 respondents (mean age 46.3±14.5 years; 66.5% females), 101 (38.4%; 95%CI 33.1–43.7%) recalled having psychotropic medicines stored at home cabinets and 72 (27.4%; 95%CI 22.4–32.3%) reported using PMS without medical advice in the last 12 months.

ConclusionsThis study revealed a high prevalence of PMS use without medical advice, including storage at home. People>59 years of age, experiencing irregular sleep and scoring high in PSS, displayed increased prevalence of storing PMS at home or using them without medical advice. The findings could potentially inform primary care providers to focus on patients most likely to be users of PMS without medical advice.

El uso de medicamentos psicotrópicos cambia según los factores socioeconómicos y el estrés percibido. El estudio tuvo como objetivo evaluar la prevalencia de uso de medicamentos y suplementos psicotrópicos (MSP) sin consejo médico, incluido el almacenamiento en el hogar y su relación con las características sociodemográficas y el estrés inferido en pacientes de atención primaria.

Materiales y métodosSe encuestó a una muestra transversal de asistentes adultos en una Unidad de Atención Primaria Urbana en Crete, Grecia, durante citas programadas regularmente durante un periodo de tres semanas en Octubre de 2020. Se distribuyó un cuestionario para investigar el uso de MSP durante los últimos 12 meses. Se adoptó la versión griega validada de la Escala de Estrés Percibido (Perceived Stress Scale 14, PSS-14) para medir el estrés percibido.

ResultadoDe 263 encuestados (edad media 46,3 ± 14,5 años; 66,5% mujeres), 101 (38,4%; IC 95%; 33,1-43,7%) recordaban tener medicamentos psicotrópicos almacenados en los armarios de sus casas y 72 (27,4%; IC 95%; 22,4-32,3%) informó haber usado MSP sin consejo médico en los últimos 12 meses.

ConclusionesEste estudio reveló una alta prevalencia de uso de MSP sin consejo médico, incluido el almacenamiento en el hogar. Las personas mayores de 59 años, que experimentaron sueño irregular y puntuaron alto en PSS, mostraron una mayor prevalencia de almacenar MSP en casa o usarlos sin consejo médico. Los hallazgos podrían informar potencialmente a los proveedores de atención primaria para que se centren en los pacientes con mayor probabilidad de usar MSP sin consejo médico.

Greece was one of the most affected countries by the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Between 2008 and 2015, the mean annual income in Greece declined from 21.194€ to 16.258€.1 Many studies were conducted in order to describe the effects of the economic crisis on mental health. A study conducted in Greece pointed out that low income was related to increased risk of depression and suicidality mainly in men.2 Another survey reported that economic burden and poor housing conditions were associated to chronic stress, especially among the unemployed and the unskilled workers.3 Other studies suggested that residents of deprived neighborhoods were at higher risk of perceived stress and more likely to develop health-risk behaviors such as low consumption of fruits, smoking and reduced physical activity.4

Additionally, some reports suggest that when objective and subjective socioeconomic status was decreased, people scored higher in perceived stress assessments.5 Furthermore, people with higher perceived stress were more likely to develop health-compromising behaviors, such as substance use, unprotected sex and unhealthy diet.6 Individuals with low income had also been found to demonstrate health-risk behaviors.6 In addition, perceived stress was negatively associated with components of social capital, with individuals having higher levels of perceived helpfulness to indicate lower levels of perceived stress.7

The consumption of psychotropic medicines also seemed to be related with social and economic conditions. Loss of employment had been reported to be associated with higher risk of psychotropic drug use, especially among men.8 Moreover, a research concerning the use of psychotropic drugs during the three latest economic crises in USA, found that antidepressant and anxiolytic prescriptions were rising, with unemployment rate increase and slower pace of income rise.9 Additionally, another study suggested that the use of substances was associated with higher levels of perceived stress.10 Therefore, perceived stress could be correlated not only to substance use but also to the psychotropic medicine consumption. Rather than that, individuals with high perceived stress levels tended to prescribe psychotropic agents more often and to visit primary health care facilities more frequently.11

Most studies exploring the use of psychotropic drugs had been based on medical prescriptions and there was limited data on psychotropic medicines or supplements (e.g. valeriana alone or in combination) stored at home or on medicines and supplements that people use without medical advice. To this end, the present study sought to estimate the prevalence of use of psychotropic medicines and supplements (PMS) without medical advice and its association with perceived stress and socio-economic characteristics in adults receiving primary health care services. A secondary aim was to examine the levels of perceived stress of people who either store PMS at home or use them without medical advice.

Materials and methodsSetting and sampleThe study was conducted at an urban primary health care unit in the city Heraklion in Greece, which serves a registered population of approximately 6000 people. A cross-sectional design was followed and the sample consisted of regularly scheduled consecutive appointments of registered adult attendees during a three-week period in October 2020. In Greece being registered to a general practitioner (GP) was not mandatory at the time the study took place and primary healthcare attendees did not need GP's referral to attend specialized healthcare units. Attendees with an appointment for any medical reason, during the study period, were eligible for the survey, provided that they: (a) were over 18 years old, (b) did not seek urgent care, (c) were able to cognitively and practically communicate the requested information. In total, 314 attendees were asked to participate and 263 accepted. Prior to study conduct, we calculated that 237–307 participants would need to be enrolled in this study to allow estimation of an anticipated PMS prevalence of 20–30% in our target population with precision ±5% and with a confidence level of 95%. This sample size would allow inclusion of about 7–14 predictors (degrees of freedom) in a binary regression model based on a 5–10 events per variable criterion, respectively.12

Ethics approvalsThis study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics and Deontology Committee of the University of Crete (Protocol no. 176/25.09.2020) and the 7th Health Regional Authority, Crete (Protocol no. 48814). Written informed consent from participants was obtained.

InstrumentsA questionnaire was distributed to investigate PMS use. The questionnaire firstly recorded main socio-demographic information (age, gender, health insurance, family status, occupational status, receipt of social welfare benefits). There were also items on buying habits, living expenses, financial comfort for vacation spending, sleeping routine and smoking habits of the participants. According to the literature, when income reduction observed (for example during an economic crisis period) people tend to ‘shrink’ vacation expenses, buy products based on price and not on brand and change their behavior toward savings and living expenses.13–15 In order to investigate PMS use, participants were asked to recall if they had used them without medical advice during the last year. Additionally, another question was asking about PMS storage at home. In both questions participants could choose any of the following psychotropic medicines and supplements: hypnotics, anxiolytics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, sedatives, valeriana alone or in combination. Responses of both questions were not summed but they were analyzed separately. Moreover, Perceived Stress Scale (14-item version) created by Cohen et al. was adopted to measure perceived stress on the day of the survey.16 The scale was validated in Greek by Andreou et al.17 This is based on 14 Likert-type questions, that are rated from 0 to 4 (0=never to 4=very often), and overall higher rating (after reversing where necessary) is indicative of greater perceived stress.17

Statistical analysisCategorical sample data were presented as counts and percent proportions and numerical data were summarized as means with standard deviation. Population estimates of proportions and means were presented using 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). Multivariable Poisson regression with log-link function and robust variance estimation18 was applied to identify characteristics of the respondents that are independently and significantly associated with storing PMS at home and using PMS without medical advice. Perceived stress was the main exposure variable and main socio-demographic factors known or expected to be associated with use of PMS were included as potential confounders (gender, age, family status, employment, health insurance, social benefits, recent reduction in living expenses, current smoking and irregular sleep) in a single model. The strength and direction of associations were presented using adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs)19 with respective 95%CIs. Collinearity among the independent variables was ruled out by examining variance inflation factors. We did not assume linear associations (on the log scale) between continuous predictor variables and the risk of PMS use without medical advice and home storage, but examined age and perceived stress scale as categorical factors based on quartile groupings. Standard errors and confidence intervals for means, proportions and aPRs were estimated using the bias-corrected and accelerated Bootstrap method with 1000 replications. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v. 28 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

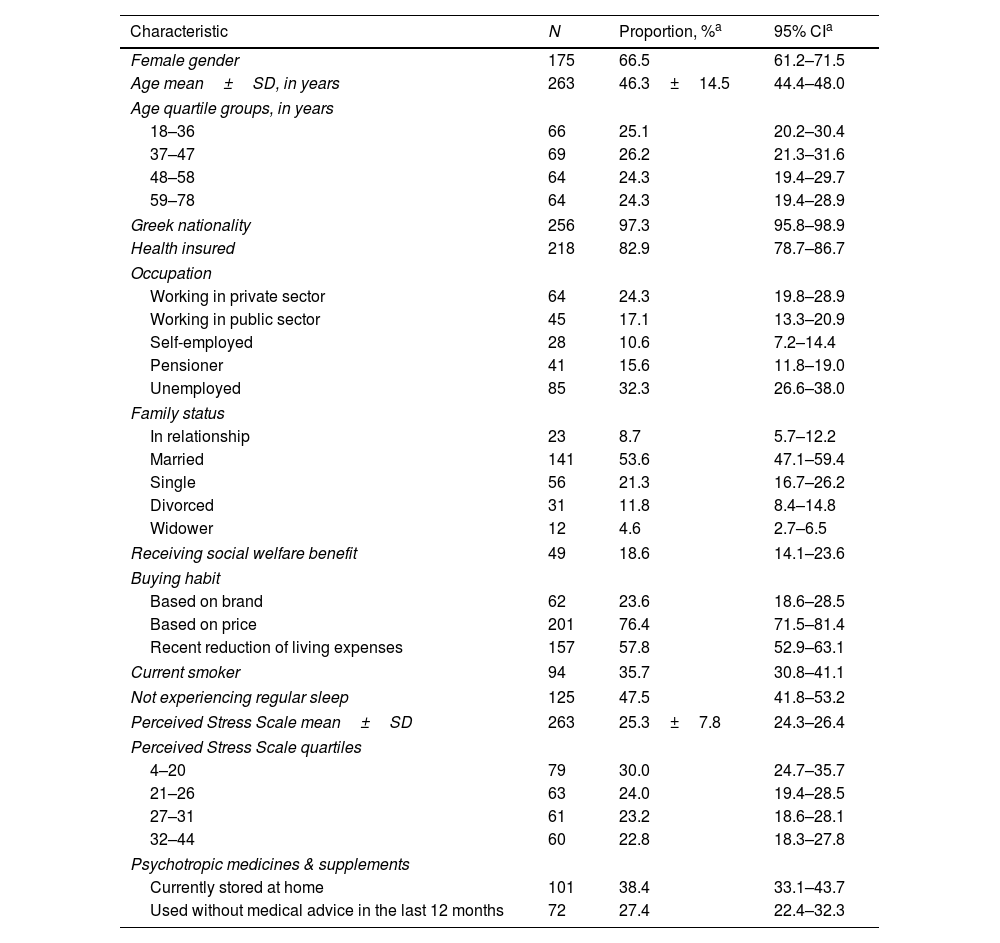

ResultsOf 314 eligible individuals approached, 263 fully completed study questionnaires (84% response rate). Main reasons for non-response included lack of time, eyesight problems, old age and poor literacy. Participants were on average 46.3±14.5 years old (age range 18–78 years) and 175/263 (66.5%) were females. The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the studied population based on a sample of N=263 respondents.

| Characteristic | N | Proportion, %a | 95% CIa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 175 | 66.5 | 61.2–71.5 |

| Age mean±SD, in years | 263 | 46.3±14.5 | 44.4–48.0 |

| Age quartile groups, in years | |||

| 18–36 | 66 | 25.1 | 20.2–30.4 |

| 37–47 | 69 | 26.2 | 21.3–31.6 |

| 48–58 | 64 | 24.3 | 19.4–29.7 |

| 59–78 | 64 | 24.3 | 19.4–28.9 |

| Greek nationality | 256 | 97.3 | 95.8–98.9 |

| Health insured | 218 | 82.9 | 78.7–86.7 |

| Occupation | |||

| Working in private sector | 64 | 24.3 | 19.8–28.9 |

| Working in public sector | 45 | 17.1 | 13.3–20.9 |

| Self-employed | 28 | 10.6 | 7.2–14.4 |

| Pensioner | 41 | 15.6 | 11.8–19.0 |

| Unemployed | 85 | 32.3 | 26.6–38.0 |

| Family status | |||

| In relationship | 23 | 8.7 | 5.7–12.2 |

| Married | 141 | 53.6 | 47.1–59.4 |

| Single | 56 | 21.3 | 16.7–26.2 |

| Divorced | 31 | 11.8 | 8.4–14.8 |

| Widower | 12 | 4.6 | 2.7–6.5 |

| Receiving social welfare benefit | 49 | 18.6 | 14.1–23.6 |

| Buying habit | |||

| Based on brand | 62 | 23.6 | 18.6–28.5 |

| Based on price | 201 | 76.4 | 71.5–81.4 |

| Recent reduction of living expenses | 157 | 57.8 | 52.9–63.1 |

| Current smoker | 94 | 35.7 | 30.8–41.1 |

| Not experiencing regular sleep | 125 | 47.5 | 41.8–53.2 |

| Perceived Stress Scale mean±SD | 263 | 25.3±7.8 | 24.3–26.4 |

| Perceived Stress Scale quartiles | |||

| 4–20 | 79 | 30.0 | 24.7–35.7 |

| 21–26 | 63 | 24.0 | 19.4–28.5 |

| 27–31 | 61 | 23.2 | 18.6–28.1 |

| 32–44 | 60 | 22.8 | 18.3–27.8 |

| Psychotropic medicines & supplements | |||

| Currently stored at home | 101 | 38.4 | 33.1–43.7 |

| Used without medical advice in the last 12 months | 72 | 27.4 | 22.4–32.3 |

NOTE. n, number of respondents; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Overall, 101 participants (38.4%; 95%CI 33.1–43.7%) reported having psychotropic medicines and supplements stored at home cabinets and 72 participants (27.4%; 95%CI 22.4–32.3%) recalled using at least one PMS without medical advice in the last 12 months. Some of the participants recalled to store more than one PMS at their home cabinets. Therefore, the most frequent PMS stored at home were listed to be valeriana, alone or in combination (n=38/144; 26.4%), followed by anxiolytics (n=34/144; 23.6%), sedatives (n=33/144; 22.9%), antidepressants (n=31; 21.5%) and antipsychotics (n=8/144; 5.6%). Valeriana, alone or in combination, was reported to be used more often by the participants (n=43/72; 59.7% of PMS users) followed by sedatives (n=12/72; 16.7%), anxiolytics (n=12/72; 16.7%), antidepressants (n=8/72; 11.1%) and antipsychotics (n=3/72; 4.2%). Four participants recalled to use 2 PMS categories and 1 participant used 3 PMS categories during the last year. From the 72 participants who reported PMS use without medical advice, 41 (56.9%) of them reported having a previous prescription.

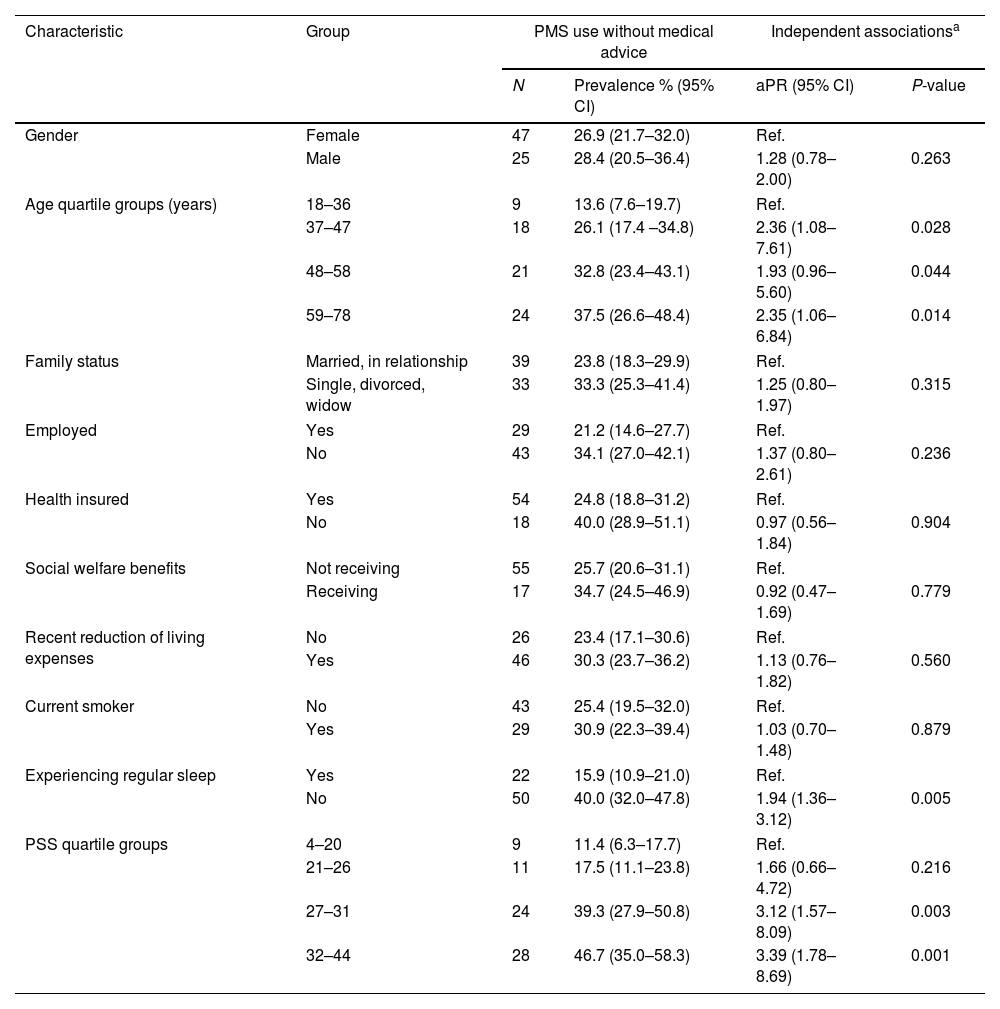

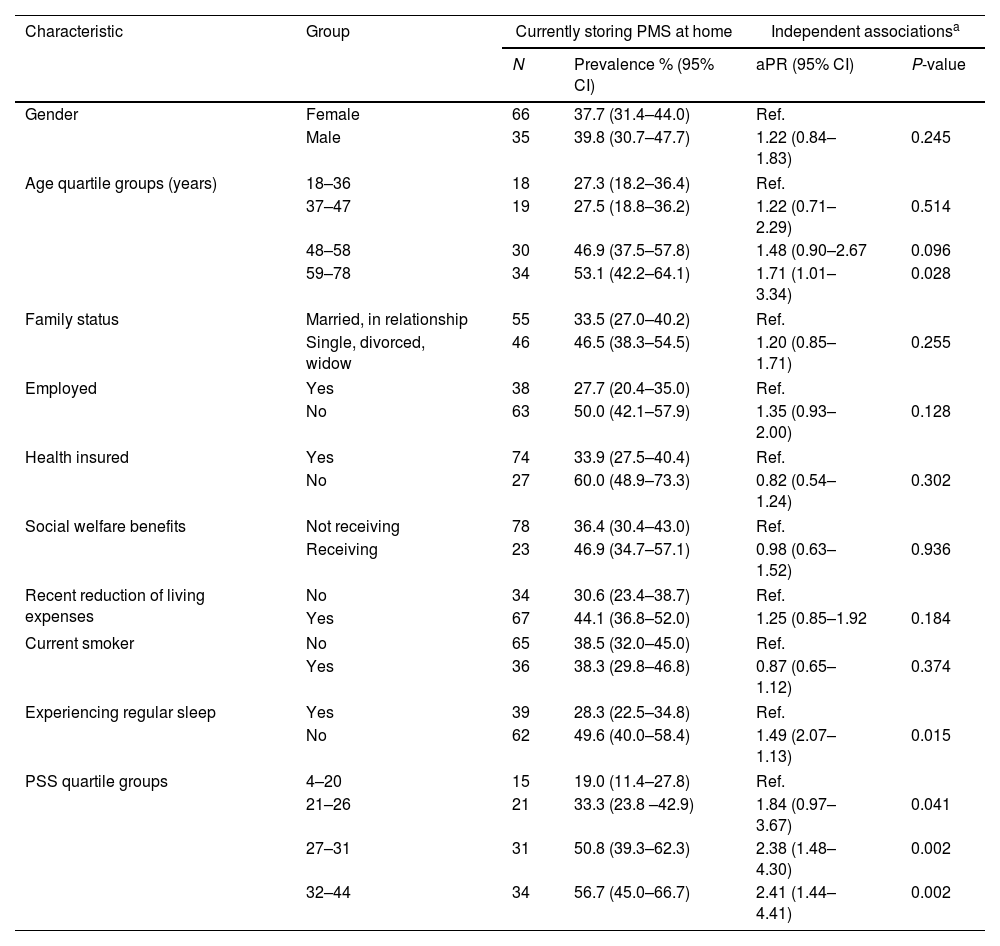

Multivariable Poisson regression identified independent and significant associations between increased one-year prevalence of PMS use without medical advice and higher age (aPR=2.35 for those aged>59 years compared to those aged<36 years, P=0.014), not experiencing regular sleep (aPR=1.94, P=0.005) and scoring high on perceived stress (aPR=3.39, P=0.001, for scores 32–44 and aPR=3.12 for scores 27–31, P=0.003, compared to scores below 20) (Table 2). The same respondent characteristics were seen to be independently and significantly associated with increased prevalence of storing PMS at home (Table 3). High proportions of storing PMS at home, reaching and exceeding 50%, were seen for people aged>59 years, unemployed citizens, those without health insurance, those receiving social welfare benefits, those experiencing irregular sleep and those who scored high (>25) on the perceived stress scale.

Self-reported prevalence of use of psychotropic medicines and supplements (PMS) without medical advice in the last 12 months according to socio-demographic characteristics and perceived stress of the respondents (N=263).

| Characteristic | Group | PMS use without medical advice | Independent associationsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Prevalence % (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Gender | Female | 47 | 26.9 (21.7–32.0) | Ref. | |

| Male | 25 | 28.4 (20.5–36.4) | 1.28 (0.78–2.00) | 0.263 | |

| Age quartile groups (years) | 18–36 | 9 | 13.6 (7.6–19.7) | Ref. | |

| 37–47 | 18 | 26.1 (17.4 –34.8) | 2.36 (1.08–7.61) | 0.028 | |

| 48–58 | 21 | 32.8 (23.4–43.1) | 1.93 (0.96–5.60) | 0.044 | |

| 59–78 | 24 | 37.5 (26.6–48.4) | 2.35 (1.06–6.84) | 0.014 | |

| Family status | Married, in relationship | 39 | 23.8 (18.3–29.9) | Ref. | |

| Single, divorced, widow | 33 | 33.3 (25.3–41.4) | 1.25 (0.80–1.97) | 0.315 | |

| Employed | Yes | 29 | 21.2 (14.6–27.7) | Ref. | |

| No | 43 | 34.1 (27.0–42.1) | 1.37 (0.80–2.61) | 0.236 | |

| Health insured | Yes | 54 | 24.8 (18.8–31.2) | Ref. | |

| No | 18 | 40.0 (28.9–51.1) | 0.97 (0.56–1.84) | 0.904 | |

| Social welfare benefits | Not receiving | 55 | 25.7 (20.6–31.1) | Ref. | |

| Receiving | 17 | 34.7 (24.5–46.9) | 0.92 (0.47–1.69) | 0.779 | |

| Recent reduction of living expenses | No | 26 | 23.4 (17.1–30.6) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 46 | 30.3 (23.7–36.2) | 1.13 (0.76–1.82) | 0.560 | |

| Current smoker | No | 43 | 25.4 (19.5–32.0) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 29 | 30.9 (22.3–39.4) | 1.03 (0.70–1.48) | 0.879 | |

| Experiencing regular sleep | Yes | 22 | 15.9 (10.9–21.0) | Ref. | |

| No | 50 | 40.0 (32.0–47.8) | 1.94 (1.36–3.12) | 0.005 | |

| PSS quartile groups | 4–20 | 9 | 11.4 (6.3–17.7) | Ref. | |

| 21–26 | 11 | 17.5 (11.1–23.8) | 1.66 (0.66–4.72) | 0.216 | |

| 27–31 | 24 | 39.3 (27.9–50.8) | 3.12 (1.57–8.09) | 0.003 | |

| 32–44 | 28 | 46.7 (35.0–58.3) | 3.39 (1.78–8.69) | 0.001 | |

NOTE. n, number of respondents who reported PMS use without medical advice; CI, confidence interval; aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio calculated by multivariable Poisson regression; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale.

Self-reported prevalence of storing psychotropic medicines and supplements (PMS) at home according to socio-demographic characteristics and perceived stress of the respondents (N=263).

| Characteristic | Group | Currently storing PMS at home | Independent associationsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Prevalence % (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Gender | Female | 66 | 37.7 (31.4–44.0) | Ref. | |

| Male | 35 | 39.8 (30.7–47.7) | 1.22 (0.84–1.83) | 0.245 | |

| Age quartile groups (years) | 18–36 | 18 | 27.3 (18.2–36.4) | Ref. | |

| 37–47 | 19 | 27.5 (18.8–36.2) | 1.22 (0.71–2.29) | 0.514 | |

| 48–58 | 30 | 46.9 (37.5–57.8) | 1.48 (0.90–2.67 | 0.096 | |

| 59–78 | 34 | 53.1 (42.2–64.1) | 1.71 (1.01–3.34) | 0.028 | |

| Family status | Married, in relationship | 55 | 33.5 (27.0–40.2) | Ref. | |

| Single, divorced, widow | 46 | 46.5 (38.3–54.5) | 1.20 (0.85–1.71) | 0.255 | |

| Employed | Yes | 38 | 27.7 (20.4–35.0) | Ref. | |

| No | 63 | 50.0 (42.1–57.9) | 1.35 (0.93–2.00) | 0.128 | |

| Health insured | Yes | 74 | 33.9 (27.5–40.4) | Ref. | |

| No | 27 | 60.0 (48.9–73.3) | 0.82 (0.54–1.24) | 0.302 | |

| Social welfare benefits | Not receiving | 78 | 36.4 (30.4–43.0) | Ref. | |

| Receiving | 23 | 46.9 (34.7–57.1) | 0.98 (0.63–1.52) | 0.936 | |

| Recent reduction of living expenses | No | 34 | 30.6 (23.4–38.7) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 67 | 44.1 (36.8–52.0) | 1.25 (0.85–1.92 | 0.184 | |

| Current smoker | No | 65 | 38.5 (32.0–45.0) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 36 | 38.3 (29.8–46.8) | 0.87 (0.65–1.12) | 0.374 | |

| Experiencing regular sleep | Yes | 39 | 28.3 (22.5–34.8) | Ref. | |

| No | 62 | 49.6 (40.0–58.4) | 1.49 (2.07–1.13) | 0.015 | |

| PSS quartile groups | 4–20 | 15 | 19.0 (11.4–27.8) | Ref. | |

| 21–26 | 21 | 33.3 (23.8 –42.9) | 1.84 (0.97–3.67) | 0.041 | |

| 27–31 | 31 | 50.8 (39.3–62.3) | 2.38 (1.48–4.30) | 0.002 | |

| 32–44 | 34 | 56.7 (45.0–66.7) | 2.41 (1.44–4.41) | 0.002 | |

NOTE. n, number of respondents who reported storing PMS at home; CI, confidence interval; aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio calculated by multivariable Poisson regression; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale.

The main findings of the study revealed that more than one third of the participants stored PMS at home and more than one quarter of the participants used them without medical advice, during the last year. The study also provides useful information regarding the social groups prone to PMS use without medical advice and storage of them at home. People aged>59 years, experiencing irregular sleep and scoring high in PSS-14 demonstrate higher prevalence of using PMS without medical advice or storing them at home.

Some evidence supported the recent imprint of financial crisis on population's mental health.20 There was extremely limited reported information, to authors’ knowledge, that explored the use of psychotropic medicines without medical advice, by collecting information from urban primary care facilities, immediately after economic crisis period, in Greece. However, some studies tried to figure on the prevalence of psychotropic drugs in primary health care settings elsewhere. A study in Brazil reported that the prevalence of psychotropic drug use in 10 primary health care settings was 38.7%.21 Similar were the results of another study in Catalonia, showing that the prevalence of prescribed psychotropic drugs in primary health care was 33.6%.22 However, a household survey carried out in Northern Ireland showed that the prevalence of psychotropic drug use in the general population was 14.9%.23 Of course, factors related to culture, community perceptions and interactions, care access, and local regulations of medicines supply may occur and quantitatively interfere with this phenomenon. The storage of medicines, in general, is very common in Greece as it was stressed out in a previous study.24 The same study also reported that people tend to own or interchange medicines from members of the family, friends, relatives, and neighbors.24 Therefore, a future study could explore whether the same ‘collective’ attitudes have occurred for the use of psychotropic medicines as well, once social and economic conditions might further power this trend.

Several studies were in partial compliance with the study findings regarding the characteristics of people using psychotropic drugs. More specifically, increased age and decreased income were related to psychotropic drug use, while older age and unemployment were connected to psychotropic drug use in women.25,26

There was limited research, to authors’ knowledge that dealt with the association between perceived stress and PMS use without medical advice. However, a study among people who used psychotropic drugs without medical advice reported 46% prevalence for depression and 41.7% prevalence for anxiety.27 A study in Argentina stressed out that approximately one third of the psychotropic medicine users were consuming them without medical advice.28 Self-medication phenomenon expands beyond mental health and former usage, condition improvement, and prescription of a similar medication were the primary reasons of self-medication.29 Additionally, the use of psychotropic drugs was higher in people with common mental disorders and those reporting both physical and mental health issues,30 and in those with low self-efficacy.31 At the same time increased prescribed psychotropic drug use was associated to higher emotional discomfort.31

Concerning perceived stress, it was reported that higher level of perceived stress was positively associated with use of psychotropic drugs.32 A more recent cohort study indicated that those with higher stress levels tended to use mental health-related services more often compared to those with lower stress levels.11 Such mental health services were more related to psychotropic drug use than long term continual therapy.11 Perceived stress could be considered a predictor for sedative drug use. According to a study, sedatives could scale down the restlessness caused by perceived stress and that was the reason of usage.33 Another research report, in the USA, stressed out that perceived stress was positively associated with alcohol and substance use,34 while a national scale survey reported gender differences with increased odds of alcohol use among males with higher perceived stress levels but not among females.35 Higher levels of perceived stress were also related to larger consumption of energy drinks among university students.36 It could be argued that there was a clear connection between use of psychotropic drugs – with or without medical advice – or other supplements and perceived stress or other mental health issues. However, little is known about the association of perceived stress and PMS use without medical advice and that was the subject that our study tried to unfold.

One of the strengths of this study was that we recorded storage of PMS at home and therefore direct potential access to them. Information was collected with self-reporting process after their full consent. Associations with economic or social condition were also indirect and not through questions of which answers were influenced by social uncertainty or a social ‘fatigue’ meaning. In addition, the research surveyed PMS use without current medical advice and the demographic characteristics of those people allowed to conclude robust associations after analysis. Moreover, the tool which was used in order to measure perceived stress was a well-known scale, used at several research settings, translated and validated into Greek17 in order to allow comparisons beyond borders.

However, the study had some limitations too. First of all, the design of the study was cross-sectional and offered a ‘snapshot’ of what occurred during study period. Additionally, data were retrospectively collected and participants had to recall their attitudes during the past year. The nature of the cross-sectional study, did not allow to the researchers to recall further information from the participants. Therefore, reporting biases cannot be excluded. Also, data were collected from only one municipal setting and for this reason generalization deserves great attention. Data regarding the participants’ health status were not obtained. However, due to the participation of regular appointments only, it can be stated that the participants did not seek urgent care. Of course, use or storing of valeriana, without active medical advice, has not the same impact with the use or storing anxiolytics, sedatives, antidepressants, or antipsychotics. However, the overall attitude appears to match with variables as age, irregular sleep, and perceived stress.

The authors also offer some empirical explanation concerning how participants could possibly obtain PMS without medical advice. PMS might be provided by older sporadic prescriptions of their own (as the use period cut-off was one year), by a friend, a family member, or a neighbor, or some of them can be bought without a medical prescription. Qualitative research can be designed, in order to better understand reasons, motivations or practices in regards to supply and use of such medicines from primary care attendees in Greece. Future studies that include a multi setting sample, around the country, are needed in order to extract results on a larger scale. Rather than that, data collection was timely allocated in the middle of COVID-19 period and we cannot exactly estimate how much this condition altered a more recent medicine use or procurement in comparison to the early months of the year.

The findings of the study could support primary care professionals to identify determinants that could probably lead to the adoption of psychotropic medicines/supplements without medical advice. A case finding approach appears to be simple and feasible, as emerged from this study. Primary care providers may clinically detect hidden mental health disorders, follow-up or refer their attendees to articulated mental health services, if it would be necessary. Additionally, this research effort may contribute to the development of specific and collaborative preventing policies and procedures. Specific interventions could be designed in order to intercept the use of psychotropic medicines/supplements without a medical advice, customized for community groups, which were identified as more exposed at a risk determinant related to a self-treatment decision. The term ‘at risk’ is used to define those who according to their socio-demographic characteristics or their perceived stress levels are prone to use PMS without medical advice in the future. In order to implement such interventions, interdisciplinary collaboration is required. For instance, services that influence health preventive strategies can collaborate with health care providers under the support of local and regional health authorities.37

ConclusionsThe current study presents data that can inform to what extend individuals store PMS at home and therefore have a higher likelihood to use them without consulting a health care professional. At the same time, it becomes obvious that primary health care professionals can have an implication in handling such eventuality. Furthermore, it is stressed out that perceived stress level assessment showed a consistent association with the use of psychotropic medicines without any or renewed medical advice. These findings could also be used for health care professional training, in order to improve services that overlap between primary and mental health care. It is also suggested that psychotropic medicine use may be a good example to focus on health care integration, in the ‘natural’ environment of primary care. Decision making for mental health issues or needs should be ‘distant’ from self-care initiatives. Similar efforts should aim to psychosocial and behavioral interventions that focus on covering citizens’ needs holistically, safely, and effectively.

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization, P.V. and E.K.S.; methodology, P.V. and E.K.S.; validation, E.I.K.; formal analysis, E.I.K.; investigation, P.V.; resources, P.V. and E.K.S.; data curation, E.I.K.; writing-original draft preparation, P.V.; writing-review and editing, E.K.S. and E.I.K.; visualization, P.V., E.K.S. and E.I.K.; supervision, E.K.S.; project administration, P.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics approvalsThe study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics and Deontology Committee of the University of Crete (Protocol no. 176/25.09.2020) and the 7th Health Regional Authority, Crete (Protocol no. 48814). Written informed consent from participants was obtained.

Informed consent statementInformed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data availability statementThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestAll authors declare no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank Professor Christos Lionis, Director of the post-graduate program “Public Health-Primary Health Care-Health Services”, as well as the academic staff of the Clinic of Social and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Crete, Greece. Also, we acknowledge the support of Dr. Fotini Anastasiou, Coordinator of the 4th Local Health Team of Heraklion, and the unit staff.