The aim was to investigate the predictive value of a single serum determination of activin A and inhibin A for classifying pregnancies of unknown location (PUL) after IVF cycles in both own fresh and donated oocytes. A case–control study conducted in a University-affiliated IVF center. Pregnancy outcomes after own fresh oocytes included 12 failing PUL, 12 ectopic pregnancies (EP) and a control group of 24 singleton intrauterine pregnancies (IUP). The same scheme was followed for the oocyte donation recipients. Inhibin A, activin A, β-hCG and Progesterone (P) were determined. In the own fresh oocytes IVF, the AUC for predicting EP vs. f failing PUL were: Activin A: 0.458 and Inhibin A: 0.60. In the oocyte donation cycles, the AUC for predicting EP were: Activin A: 0.521 and Inhibin A: 0.906. Our result cannot be extrapolated to spontaneously conceived pregnancies, since values of some of these biomarkers are higher after induced ovulation compared with natural cycle. It will be necessary to continue the search of a biomarker which accurately predict pregnancy evolution.

El objetivo del estudio fue investigar el valor predictivo de una única determinación sérica de activina A e inhibina A para clasificar las gestaciones de localización desconocida (GLD) tras ciclos de FIV tanto con ovocitos de la propia paciente como donados. Estudio de casos y controles realizado en un centro de FIV asociado a la universidad. Los resultados en el grupo de ovocitos propios frescos incluyeron 12 abortos bioquímicos, 12 embarazos ectópicos (EE) y un grupo control de 24 embarazos intrauterinos únicos. El mismo esquema se siguió para los receptores de donación de ovocitos. Se determinaron inhibina A, activina A, β-hCG y progesterona (P). En el grupo de FIV con ovocitos propios, el área bajo la curva para predecir EE frente a aborto bioquímico fue: activina A: 0,458 e inhibina A: 0,60. En los ciclos de donación de ovocitos, las áreas bajo la curva para predecir EE fueron: activina A: 0,521 e inhibina A: 0,906. Nuestro resultado no se puede extrapolar a embarazos concebidos espontáneamente, ya que los valores de algunos de estos biomarcadores son más altos después de la ovulación inducida en comparación con el ciclo natural. Será necesario continuar la búsqueda de un biomarcador que prediga con precisión la evolución de la gestación.

The term PUL (pregnancy of unknown location) defines a situation in which a positive pregnancy test and an empty uterus with no signs of intrauterine or extrauterine pregnancy on a TVS (transvaginal scan) coexist (Kirk et al., 2009a; Barnhart et al., 2011). To depict between early pregnancy loss and an EP, β-hCG and progesterone (P) are normally used in clinical practice. However, after IVF treatment the diagnosis is often protracted and costly. The development of a single diagnostic serum biomarker would minimize these problems.

Recent studies have shown that a single serum determination of Activin A and Inhibin A may identify patients at risk of EP (Florio et al., 2007; Segal et al., 2008), while others do not support these findings.

Activin A and Inhibin A are secreted by the ovary and placenta in early pregnancy (Cartwright et al., 2009; Muttukrishna et al., 1997; Fowler et al., 1998), thus the presence of multiple corpora lutea resulting from controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) could affect the evaluation of these markers in the prediction of the outcome of PUL. On the other hand, in the oocyte donation setting, corpus lutea are not present, as these patients do not undergo COS. For this reason we included also a group of donor egg pregnancies as a model which has no corpus luteum.

The objective of the present study was to analyze the predictive value of a single serum determination of serum activin A, inhibin A, human chorionic gonadotrophin (β-hCG) and P for accurately diagnosing PUL in IVF, especially the early diagnosis of EP, in both own fresh and oocyte donation cycles.

Materials and methodsThis case-control study included 96 pregnancies achieved by IVF in a University-affiliated IVF center between January 2008 and April 2009. The study was approved by the local Ethical Review Board.

Briefly, IVF treatment cycles generally consist of gonadotrophin stimulation associated to a gonadotrophin releasing hormone analog to prevent LH surge. Transvaginal oocyte retrieval and subsequent embryo transfer (ET) are performed as described elsewhere (Soares et al., 2005; Melo et al., 2006). Luteal phase support was provided by vaginal micronized progesterone (P) until 12 weeks of pregnancy.

A venous blood sample was withdrawn 16 days after ET for β-hCG assay. Establishment of pregnancy was defined by ≥10IU/L; when levels were between 10 and 100IU/L, a new β-hCG determination was done 48h later. If hormonal level was suitable (i.e. 2 fold increase), the patient was submitted for a control approximately one week later.

In this control, made 22–27 days after oocyte retrieval, women also underwent a TVS examination using a 6.5-MHz transducer (Voluson 730 Pro V; General Electric, Madrid, Spain), to qualify the pregnancy as ectopic, intrauterine or of unknown location in the case that no clear ultrasound evidence of pregnancy can be observed. Our PUL rate in the period study was 8%, and therefore acceptable (<15%) (Condous et al., 2006a).

Women were followed up in our center until the final diagnose was done. Patients whose controls were performed in other institutions were not included.

Pregnancy outcomes after own fresh oocytes included 48 cases: 12 spontaneously resolved PUL or failing PUL (FP), spontaneous resolution of serum β-hCG to undetectable levels (Barnhart et al., 2011), 12 EP (diagnosed by ultrasound) and a control group of 24 singleton ongoing intrauterine pregnancies (IUP) matched for age, body mass index (BMI), cause of sterility and ART procedure. A sample size of 12 per group has been considered to rule of thumb for a pilot study (Julious, 2005). Only singleton pregnancies were included because the feto-placental unit is a source of activin and Inhibin A and concentrations of these hormones would be higher in multiple pregnancies, wherein the placental mass is greater (Cartwright et al., 2009; O’Connor et al., 1999).

The same scheme was followed for the oocyte donation recipients: 12 FP, 12 EP, and a control of 24 singletons IUP. For the recipients we used a protocol of endometrial preparation with oestrogens, hormonal replacement therapy (HRT). In case of ovarian function a GnRH antagonist was administered daily from the first day of the period and during 7 days (Vidal et al., 2010) or down-regulated in the mid lutheal phase of the previous cycle with a single-dose of depot GnRH-agonist (Soares et al., 2005). Lutheal phase was supported by daily vaginal administration of micronized intravaginal P.

Serum assayBlood samples were taken at the time of the first ultrasound examination. After the aliquots were used to measure β-hCG and P, samples were stored at −20°C. Assays were done in these samples collected at the initial visit, without knowledge of pregnancy outcome, and results of P, activin A and Inhibin A did not influence treatment.

β-hCG and inhibin A were determined by chemiluminescence and activin A using ELISA. Measurements were performed in duplicate.

β-hCG assay (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, California, USA) had a sensitivity of 0.5mIU/ml, with an intra-observer coefficient of variation (CV) of 2.1% and inter-observer CV of 3.3%; no cross reactivity to LH, FSH and TSH was shown. Progesterone assay (IMMUNOTECH, Marseille, France) had a sensitivity of 0.05ng/ml, with a within-assay CV less than 5.8% and interassay CV less than 9%; the cross reaction with 17-OH progesterone, estriol, 17β estradiol, testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone was less than 0.3%. The Activin A assay (Oxford Bio-Innovation Ltd., Oxfordshire, United Kingdom) had a limit of detection of 78pg/ml, with an intraobserver CV of 2% and interassay CV of 4%, without cross-reaction with Inhibin A, Activin B or inhibin B. Inhibin A assay (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, California, USA) had a sensitivity of 1pg/ml, with an intraassay CV of 4% and interassay CV less of 5%; the cross reaction with Activin B, FSH, LH, Prolactin, TSH and α2 macroglobulin was less than 0.006%.

Statistical analysisData were analyzed with the SPSS software (Stadistical Package for Social Sciences, 17.0). Quantitative variables were compared by the “t” test for the independent samples for normal distribution, and by the Mann Whitney test for non normal distributions. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, in a two-tailed analysis. For the diagnosis capability of all the biomarkers analyzed, a receiving operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis was performed by defining the area under the curve (AUC) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) for them all to predict EP and failing PUL when PUL was observed.

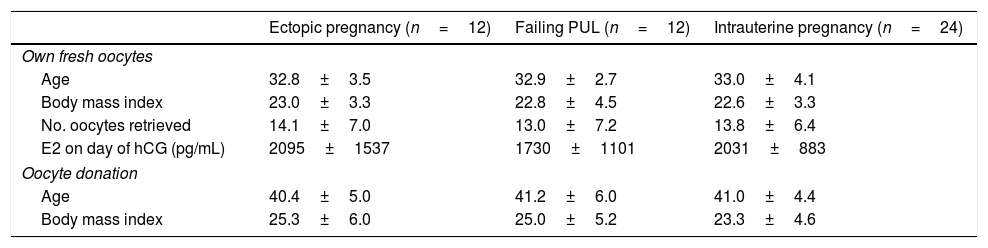

ResultsAge, BMI, number of oocytes retrieved and serum E2 levels on the day of triggering were similar among the different pregnancy types in the own fresh oocyte cycles, nor were there any age- or BMI-related differences between groups in the oocyte donation cycles (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics of patients in fresh own oocytes and oocyte donation cycles.

| Ectopic pregnancy (n=12) | Failing PUL (n=12) | Intrauterine pregnancy (n=24) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Own fresh oocytes | |||

| Age | 32.8±3.5 | 32.9±2.7 | 33.0±4.1 |

| Body mass index | 23.0±3.3 | 22.8±4.5 | 22.6±3.3 |

| No. oocytes retrieved | 14.1±7.0 | 13.0±7.2 | 13.8±6.4 |

| E2 on day of hCG (pg/mL) | 2095±1537 | 1730±1101 | 2031±883 |

| Oocyte donation | |||

| Age | 40.4±5.0 | 41.2±6.0 | 41.0±4.4 |

| Body mass index | 25.3±6.0 | 25.0±5.2 | 23.3±4.6 |

Serum inhibin A (105.0 vs. 11.7pg/ml) and progesterone (60.9 vs. 10.0ng/ml), but not activin A concentrations (0.35 vs. 0.375pg/ml; p=0.44) were elevated in IUP pregnancies arising from IVF when compared with oocyte donation cycles (p<0.001), probably as a result of the presence of multiple corpora lutea resulting from ovarian hyperstimulation. However, there was no significant relation between the number of oocytes in IUP after IVF and the serum levels of activin A (p=0.5) or inhibin A (p=0.1).

Indeed, in EP when compared pregnancies arising from IVF with those from oocyte donation neither activin A (0.32 vs. 0.33pg/ml; p=0.96) nor inhibin A concentrations (18.8±15.01 vs. 5.2±8pg/ml; p=0.13) were elevated.

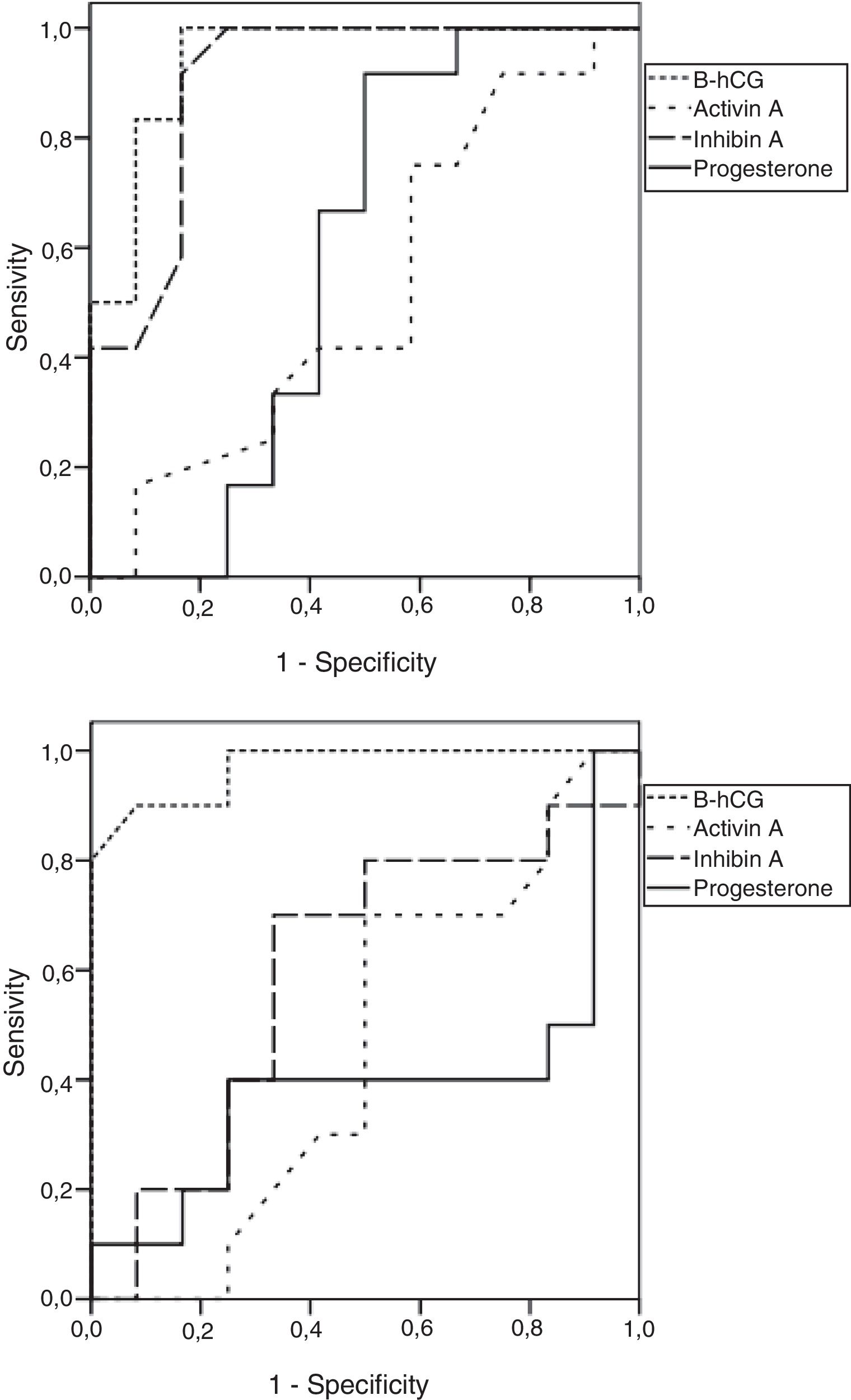

Fig. 1 shows the ROC curves for predicting the EP for all the biomarkers analyzed: in the own fresh oocytes IVF cycles, only beta-hCG appeared to be highly predictive of EP, while both beta-hCG and inhibin A were predictive of EP in the oocyte donation cycles.

β-hCG was also a good predictor of failing PUL in both IVF and oocyte donation cycles. Inhibin A was useful only in the donated group, while activin A was poor at predicting PUL in either own fresh IVF or oocyte donation cycles (Table 1).

DiscussionThe present study shows the behavior of four different biomarkers (activin A, inhibin A, β-hCG and P) with three possible outcomes after diagnosing embryo implantation (EP, failing PUL and IUP) in two different scenarios (own fresh oocytes IVF and oocyte donation cycles).

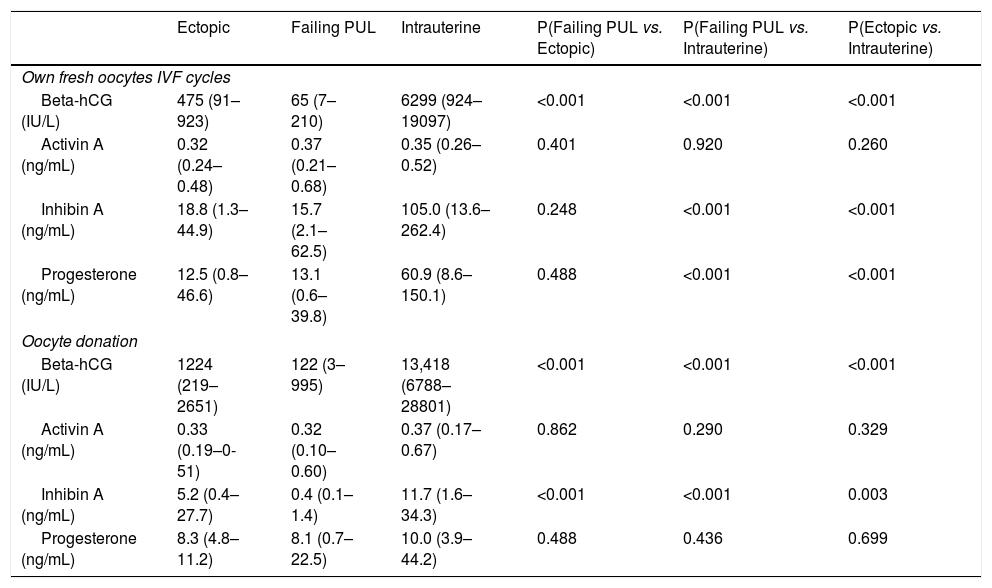

In the own fresh IVF cycles that ended with failing PUL, activin A did not significantly differ from EP (0.37 vs. 0.32pg/ml, p=0.4) or IUP (0.37 vs. 0.35pg/ml, p=0.92). Inhibin A was lower in failing PUL compared to IUP (p<0.001), but not to EP. The value in EP was significantly lower compared with IUP (18.8 vs. 105pg/ml, p<0.001) (Table 2).

Mean (minimum-maximum) values of Beta-hCG, Activin A, Inhibin A and Progesterone in ectopic, failing PUL and intrauterine pregnancies. Comparisons were made with a non parametric test (Mann Whitney).

| Ectopic | Failing PUL | Intrauterine | P(Failing PUL vs. Ectopic) | P(Failing PUL vs. Intrauterine) | P(Ectopic vs. Intrauterine) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Own fresh oocytes IVF cycles | ||||||

| Beta-hCG (IU/L) | 475 (91–923) | 65 (7–210) | 6299 (924–19097) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Activin A (ng/mL) | 0.32 (0.24–0.48) | 0.37 (0.21–0.68) | 0.35 (0.26–0.52) | 0.401 | 0.920 | 0.260 |

| Inhibin A (ng/mL) | 18.8 (1.3–44.9) | 15.7 (2.1–62.5) | 105.0 (13.6–262.4) | 0.248 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Progesterone (ng/mL) | 12.5 (0.8–46.6) | 13.1 (0.6–39.8) | 60.9 (8.6–150.1) | 0.488 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Oocyte donation | ||||||

| Beta-hCG (IU/L) | 1224 (219–2651) | 122 (3–995) | 13,418 (6788–28801) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Activin A (ng/mL) | 0.33 (0.19–0-51) | 0.32 (0.10–0.60) | 0.37 (0.17–0.67) | 0.862 | 0.290 | 0.329 |

| Inhibin A (ng/mL) | 5.2 (0.4–27.7) | 0.4 (0.1–1.4) | 11.7 (1.6–34.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Progesterone (ng/mL) | 8.3 (4.8–11.2) | 8.1 (0.7–22.5) | 10.0 (3.9–44.2) | 0.488 | 0.436 | 0.699 |

On the contrary, β-hCG levels were significantly lower in failing PUL compared to both EP and IUP. Also β-hCG levels were significantly lower in EP compared with IUP. Progesterone followed the same pattern as inhibin A, levels were lower in failing PUL compared to IUP, but not when compared to EP (Table 2).

The values of the biomarkers in the oocyte donation group are shown in Table 2. Activin A was similar for all three possible situations, as it was in the IVF own fresh cycles. However, Inhibin A was significantly different in failing PUL compared with EP (0.4 vs. 5.2pg/ml, p<0.001) and IUP (0.4 vs. 11.7pg/ml, p<0.001). The EP levels were lower compared with IUP (5.2 vs. 11.7pg/ml, p=0.003) (Table 2).

For the own fresh oocytes cycles, in which COS was performed, Inhibin A and P, both produced by the corpora lutea, were significantly higher in IUP compared to EP and failing PUL, but were unable to depict between EP and failing PUL. Beta-hCG was able to predict failing PUL and EP. Activin showed similar serum levels regardless of pregnancy outcome, but was unable to predict either EP or failing PUL. This contrasts with previous studies in which Activin A levels were different in these situations in spontaneous (Florio et al., 2007; Kirk et al., 2009b; Florio et al., 2011) and IVF pregnancies (Akan et al., 2011).

Our ROC analysis showed that Activin A was not a good predictor of PUL outcome as none of the analyzed cut-off points displayed good predictive capability. These findings are consistent with those observed by others (Fowler et al., 1998; Barnhart et al., 2011; O’Connor et al., 1999; Kirk et al., 2009b; Florio et al., 2011; Akan et al., 2011; Warrick et al., 2012) in spontaneous pregnancies. In the women who underwent IVF, inhibin A levels were also significantly lower in EP and FP compared with singleton ongoing pregnancies (Yohkaichiy et al., 1993; Treetampinich et al., 2000; Hauzman et al., 2004).

Our data showed that Inhibin A was not a good predictor of failing PUL in IVF. These findings differed from those previously observed in spontaneous pregnancies (Kirk et al., 2009b) and IVF (Hauzman et al., 2004). Regarding EP, we found that inhibin A was not a useful biomarker, which agrees with other studies (Kirk et al., 2009a; Yohkaichiy et al., 1993).

In the oocyte donation model, inhibin A and P remained low regardless of pregnancy outcome since, in this case, no corpora lutea were present. Yet between these two biomarkers, only inhibin A measurements showed capability for predicting EP in the oocyte donation cycles. β-hCG remained predictive of EP in the oocyte donation model.

Inhibin A and β-hCG were also predictive of failing PUL in this context. However, the presence of a case in the ectopic group with significantly higher inhibin A should be noted.

With regard to the classic biomarkers, β-hCG was found to be a good predictor of FP and EP, whilst recently findings showed single serum hCG level had the lowest diagnostic value, while strategies using serum hCG ratios, either alone or incorporated in logistic regression models, showed reasonable diagnostic performance for EP (Van Mello et al., 2012; Condous et al., 2005a, 2005b, 2006b). Differences in this point could be related to the sample size of our study.

Moreover, activin A did not provide any predictive value for either EP or failing PUL in the oocyte donation model, and the same occurred in own fresh oocyte IVF cycles. Our data on Activin and Inhibin A were similar to those presented in prior publications (Treetampinich et al., 2000; Lockwood et al., 1997).

To the best of our knowledge, these data represent the first evidence that Activin A is not useful for predicting the outcome of women with PUL in ART. At the same time, this work provides estimates of the possible utility of inhibin A as a predictor of PUL in oocyte donation cycles.

In early pregnancy, Activin A is secreted from the ovary and placenta (Muttukrishna et al., 1997; Wen et al., 2008) while the fundamental source seems to be the trophoblast (Florio et al., 2007; Petraglia et al., 1987). Previous studies have reported a major contribution of circulating inhibin A from either the ovary (Rombauts et al., 1996) or the placenta in spontaneous (Petraglia et al., 1987; Birdsall et al., 1997) and in IVF pregnancies. The apparent discrepancies could be due to the different assay used, the stage of the gestation and the treatment used in IVF cycles. Analysis of IVF pregnancies achieved using donated eggs allows for the separation of the contribution of the fetoplacental unit from that of the corpus luteum, since donor oocyte conceptions are usually brought in women with ovarian failure or complete ovarian suppression with GnRH analogues. Our study demonstrates that inhibin A, but not activin A, concentrations were elevated in IUP pregnancies arising from IVF when compared with oocyte donation cycles (p<0.001), and provide evidence that inhibin A is a product not only of the fetoplacental unit in this period. Indeed, we used progesterone for lutheal support, which has an effect directly by supporting endometrium but not significant effect on function of the corpus luteum.

In conclusion, none of the biomarkers we analyzed showed good diagnosis capability to localize PUL after one single determination. Clinical follow-up with serial serum beta-hCG monitoring, and TVS is apparently nowadays the best option to classify a given PUL. Inhibin A seems useful only in oocyte donation. For this reason, research into biomarkers to accurately predict pregnancy evolution as early as possible should continue.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interests.