This study sought to compare the ovarian response and follicular dynamics after stimulation with HP-hMG vs. rFSH+rLH in ovulation induction treatment. We hypothesized that the administration of 75IU of HP-hMG should be similar to 75IU of rFSH+75IU of rLH in terms of ovarian response.

Material and methodProspective, randomized, open-label study was conducted in the Instituto Valenciano de Infertilidad (IVI). It included 75 patients<39 years undergoing IUI, of whom 66 were randomly assigned to one of the following groups: (1) 75IU/day rFSH+75IU/day rLH; or (2) 75IU/day HP-hMG. The objective was to compare follicular dynamics and the sample size was calculated to detect a difference in the increase in serum estradiol (E2) of 75pg/mL between days 1 and 6 of stimulation.

ResultsNo differences were observed in terms of serum E2 increase, follicles recruited on day 6, serum E2 the day of hCG administration and days of stimulation. Rates of cancellation, pregnancy, pregnancy loss and clinical pregnancy between the two groups were similar. Although no statistically significant differences in the distribution of mature, medium-sized and small follicles were observed on the day of hCG administration, the number of medium-sized follicles tended to be lower in the group receiving HP-hMG.

DiscussionStimulation with rFSH+rLH or HP-hMG offers similar results in terms of ovarian response, demonstrating that bioactivity is comparable between the two treatments when administered in the same ratio. The additional advantage of HP-hMG is the lower proportion of medium-sized follicles, which could be responsible for an increased risk of OHSS and multiple gestations. Administration of HP-hMG can be a valid and safe option for the induction of ovulation in IUI.

El presente estudio pretende comparar la respuesta ovárica y la dinámica folicular tras estimulación con HP-hMG vs. FSHrec+LHrec en tratamientos de inducción de la ovulación. Nuestra hipótesis es que la administración de 75UI de HP-hMG debe resultar en una respuesta ovárica similar a la administración de 75UI de FSHrec+75UI de LHrec.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo aleatorizado abierto realizado en el Instituto Valenciano de Infertilidad (IVI). Incluye 75 pacientes <39años sometidas a inseminación intrauterina, de las que 66 fueron asignadas aleatoriamente a uno de los siguientes grupos: 1)75UI/día FSHrec+75UI/día LHrec, o 2)75UI/día HP-hMG. El objetivo fue comparar la dinámica folicular, calculándose el tamaño muestral con el fin de detectar una diferencia en el incremento de estradiol sérico (E2) de 75pg/ml entre los días 1.° y 6.° de estimulación.

ResultadosNo se observaron diferencias significativas en cuanto al incremento de E2 sérico, número de folículos reclutados en el día 6.° de estimulación, E2 sérico el día de la administración de hCG y días de estimulación. Las tasas de cancelación, embarazo, aborto y embarazo evolutivo fueron similares entre ambos grupos. Aunque no se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la distribución de folículos de tamaño maduro, intermedio o pequeño el día de la administración de la hCG, el número de folículos de tamaño intermedio tiende a ser inferior en el grupo que recibió HP-hMG.

DiscusiónLa estimulación con FSHrec+LHrec o HP-hMG ofrece resultados similares en términos de respuesta ovárica, demostrando que la bioactividad de ambos compuestos es comparable cuando son administrados en la misma proporción. La ventaja adicional de la administración de HP-hMG es la menor proporción de folículos de tamaño intermedio, los cuales pueden ser causa de un incremento del riesgo de síndrome de hiperestimulación y gestación múltiple. La administración de HP-HMG puede ser una opción válida para la inducción de la ovulación en inseminación artificial.

Intrauterine insemination (IUI) is an assisted reproductive technology (ART) used mainly in cases of mild male factor, ovulation disorders, unexplained infertility and in women without a male partner who wish to have children. The process may be carried out in the context of a patient's spontaneous natural cycle, but it is usually associated with treatment of ovulation induction with clomiphene citrate or ovarian stimulation with gonadotropins, with the aim of developing multiple mature follicles and thus increasing the success rate of the technique by providing more oocytes capable of being fertilized (Veltman-Verhulst et al., 2012; Balasch, 2004; Hughes, 1997; Guzick et al., 1999). The ovarian stimulation protocols most commonly used for IUI are usually carried out with exogenously administered gonadotropins, mainly follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG).

During treatment with FSH, it is possible to add luteinizing hormone (LH). This supplementation has been studied in IVF treatments, where there has been a positive effect on its use in patients with low response and/or over 35 years (Bosch et al., 2011; Marrs et al., 2004; Humaidan et al., 2004). The rationale for its use is based on the intrafollicular LH level inducing the secretion of androgens, which are the precursors of oestrogens and are found in lower concentrations in older patients (Davison et al., 2005). In the context of IUI treatments, the use of LH activity is less clear, but so far, the use of HP-hMG has shown no inferiority in clinical pregnancy rates compared to the use of FSH in IUI cycles (Sagnella et al., 2011).

Both, rFSH as well as rLH, were developed through genetic engineering techniques, providing an effective, safe, uniform and well-tolerated alternative. Their high purity facilitates characterization and quantification. Co-administration is not associated with the occurrence of pharmacokinetic interactions or substantial variations in the response to FSH or LH bioavailability (Burgués, 2001; le Cotonnec et al., 1998).

Highly purified or ultrapure hMG (HP-hMG) is obtained from the chromatographic ultrapurification of gonadotropic fractions contained in the urine of menopausal women. This process increases the homogeneity of the extractive product, which is characterized by FSH and LH activity in a 1:1 ratio more consistent than that of traditional hMG. LH activity is due to the product containing human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), thus mimicking the function of LH. hCG is six-fold more active than LH, and that is why, approximately, 10IU of hCG that is in a 75IU ampule of hMG are equivalent to 75IU of LH activity (Choi and Smitz, 2014; Filicori et al., 2005). At the same time, it substantially reduces the amount of protein contaminants and enables subcutaneous administration in an aqueous solution. The basic pharmacokinetic characteristics of HP-hMG (maximum concentration, time to maximum concentration and area under the curve) do not differ from those of conventional hMG.

Although recombinant gonadotropic preparations have been on the market since the 1990s, the debate on the comparability of level of clinical efficacy persists today. Multiple studies have compared them in ovarian stimulation in in vitro fertilization cycles (IVF) (Westergaard et al., 2001, 2011; Andersen et al., 2006; Rashidi et al., 2005; Goldfarb and Desai, 2003; van Wely et al., 2003; Kilani et al., 2003; Gordon et al., 2001). The main conclusion of these studies is that there is insufficient evidence to conclude that some are more effective than others in terms of clinical pregnancy, although different parameters of ovarian response have been observed (Devroey et al., 2012; Bosch et al., 2008; Rashidi et al., 2005).

Also, in the context of IVF, initial recruitment with rFSH+rLH was compared against HP-hMG and a similar follicular response was observed. However, there are few randomized studies available in the literature comparing different gonadotropic products in IUI.

Among them are several prospective randomized studies comparing urinary FSH versus rFSH (Gerli et al., 2004; Isaza et al., 2003; Matorras et al., 2000); urinary FSH vs. rFSH vs. hMG (Demirol and Gurgan, 2007); rFSH vs. hMG (Sagnella et al., 2011; Platteau et al., 2006); and HP-hMG vs. rFSH+rLH (Moro et al., 2015).

Demirol and Gurgan (2007) concluded that rFSH achieves higher clinical pregnancy rates but at the expense of an increased number of mature follicles. By contrast, other studies have shown similar ovulation rates with rFSH and HP-hMG, and have pointed out that the addition of hMG decreases the number of medium-sized follicles and thus reduces the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and multiple pregnancies (Moro et al., 2015; Sagnella et al., 2011). In fact, it was described that the number of cancelled cycles due to risk of OHSS and multiple pregnancies was significantly higher in the rFSH group than in the HP-hMG group. That is why it has been suggested that the addition of LH activity is a good alternative in anovulatory patients in the WHO's Group II.

A randomized study recently published by Moro et al. (2015) found no differences in ongoing clinical pregnancy rate in women older than 35 years treated with HP-hMG vs. rFSH+rLH who underwent IUI treatment. An interesting finding of this study is that the number of cycles cancelled due to OHSS risk was significantly lower in the group receiving HP-hMG.

These latter outcomes are in line with the study presented in this article, which sought to compare the ovarian response in younger patients between ovarian stimulations with HP-hMG vs. LH+rFSH in ovulation induction treatment for intrauterine insemination.

The main objective of this study is to evaluate the initial ovarian response in terms of follicular recruitment via estradiol (E2) production of HP-hMG compared to the administration of rFSH and rLH, in equal proportions, in order to clarify whether the FSH and LH activities present in HP-hMG is equivalent to the well-established activity of the recombinant products. The secondary objective is to evaluate both protocols in terms of clinical outcomes.

Material and methodsDesign and scope of studySingle-centre, prospective, randomized controlled trial (RCT), open study in the Instituto Valenciano de Infertilidad (IVI) in Valencia, Spain, was conducted. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board and the Institution's Ethics Committee before starting the study. The registration number on clinicaltrials.com is NCT00820482.

PatientsThe eligible population for the study were all those patients with primary or secondary mild to moderate male infertility, and patients with unexplained infertility, who were undergoing their 1st or 2nd cycle of IUI and met the following inclusion criteria:

- -

Sterility>1 year duration

- -

Age 18–39 years

- -

Body mass index (BMI): 18–30kg/m2

- -

Regular menstrual cycles (26–32 days)

- -

Baseline FSH and LH<10IU/L; baseline serum E2<75pg/mL in a period not exceeding 3 months prior to initiation of treatment.

- -

Tubal patency demonstrated by hysterosalpingography (HSG)

- -

Motile sperm count after swim-up (MSC)>3 million/mL.

Excluded from the eligible population were all those who presented one of the following criteria:

- -

Polycystic ovary syndrome (POS).

- -

Grade III–IV endometriosis, diagnosed by transvaginal ultrasound.

- -

Congenital or acquired uterine pathology (polyps, intracavitary fibroids, Müllerian abnormalities, etc.)

- -

Hormonal treatment of any type in the 3 months prior to the study.

- -

Relevant, endocrine or metabolic systemic diseases.

- -

Previous history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

- -

Hypersensitivity to any of the products included in the study.

Patients ultimately included were randomized to one of two study groups:

- -

Group A: 75IU/day of HP-hMG (Menopur®, Ferring, Copenhagen, Denmark)

- -

Group B: 75IU/day of rFSH (Gonal®, Merck-Serono, Geneva, Switzerland)+75IU/day of rLH (Luveris®, Merck-Serono, Geneva, Switzerland)

- -

Group A: Start stimulation (day 3 of cycle±1 day) with 75IU/day of HP-hMG administered subcutaneously (sc.) for 5 consecutive days. Determinations of estradiol (E2) levels on day 1 and day 6 of stimulation were performed as well as on the day of hCG administration. The dose remained fixed to the end of the stimulation.

- -

Group B: Start of stimulation (day 3 of cycle±1 day) with 75IU/day of rFSH+75IU/day of rLH, administered together sc. for 5 consecutive days. After hormonal (serum E2) and ultrasound control, the doses of both preparations were kept constant until the end of the stimulation.

In both groups, the final oocyte maturation and ovulation was induced with a single injection of 250μg of recombinant hCG subcutaneously (Ovitrelle®, Merck-Serono, Geneva, Switzerland), when at least one follicle reached a diameter ≥17mm. The cycle was cancelled if 4 or more mature follicles developed risk of OHSS and multiple pregnancies.

Primary endpoint was to compare the increase in serum E2 after 5 days of stimulation and the follicular dynamics after ovarian stimulation in IUI cycles when using HP-hMG as opposed to rFSH with rLH, in order to assess whether the bioactivity is comparable between the two treatments in the same FSH-LH ratio.

Variables analysed- -

Increase of serum E2 (pg/mL) between the first day of stimulation (d1), and after 5 days of stimulation (d6).

- -

Number of follicles recruited (>10mm) on day 6 of stimulation.

- -

Serum E2 on day of hCG administration (pg/mL).

- -

Number of small (≤14mm), medium-sized (15–16mm) and mature (≥17mm) follicles on the day of hCG dosing.

- -

Duration of stimulation (days).

- -

Total dose administered (IU).

- -

Cancelled cycles.

- -

Motile sperm count (MSC) in both IUIs.

- -

Clinical pregnancy rate.

- -

Pregnancy loss rate.

- -

Ongoing pregnancy rate (>12 weeks).

All semen samples were prepared based on the swim-up procedure. Briefly, the ejaculates were diluted 1:1 (v/v) with Sperm Medium (MediCult®, Jyllinge, Denmark), centrifuged at 400×g for 10min, and the supernatant was discarded. Aliquots of 0.5–1mL of fresh medium were deposited on the plate, and incubated for 45min at 37°C, with the tubes inclined at an angle of 45°. After this period, the top 0.5mL was taken. Ten microliter aliquots were used to analyse sperm concentration, motility and morphology after preparation. The remaining sample was loaded into the insemination catheter to deposit at the bottom of the uterine cavity.

The IUI was conducted on 2 consecutive days after administration of hCG, a procedure routinely performed at our centre at the time of completion of the study. The second day of insemination, luteal phase support was started with 200mg/day of natural micronized progesterone administered vaginally (Progeffik®, Laboratorios Effik, Madrid, Spain, or Utrogestan®, SEID, Barcelona, Spain). A quantitative analysis of serum β-hCG was conducted 2 weeks after insemination. In case of pregnancy, the patient continued with the administration of vaginal progesterone until week 8 of gestation and the first ultrasound was performed at 3 weeks of the IUI to evidence the number and location of the gestational sac(s). The last ultrasound was performed at 8–10 weeks to diagnose the presence of ongoing clinical pregnancy. Pregnancies that are not clinically controlled in our centre are followed periodically by telephone until the time of delivery.

Measurement of serum E2To measure serum E2 a microparticle enzyme-linked immunoassay was run using an AxSym System (Abbott Científica, S.A., Madrid), with a sensitivity of 28pg/mL and intra- and inter-observer coefficients of 6.6% and 7.7%, respectively.

Sample sizeThe sample size calculation was performed with the main objective of detecting a difference in serum E2 increase between day 1 and day 6 of stimulation of 75pg/mL bilaterally between both groups, with an estimated standard deviation of 100pg/mL, a 95% confidence interval (error α=5%) and a statistical power of 80% (error β=20%). To meet these criteria, 28 patients in each group were required, and therefore, a total of 56 patients. A loss rate of 20% was estimated, so the final number of patients needed was 66. The distribution was performed using computer generated block randomization, and was performed on the starting day of the stimulation.

Statistical analysisFor statistical analysis, the mean comparison test was used for two independent groups: Student “t” test for quantitative variables, and the χ2 test for comparison of categorical variables. The analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Chicago, IL) for Windows, version 17.0.

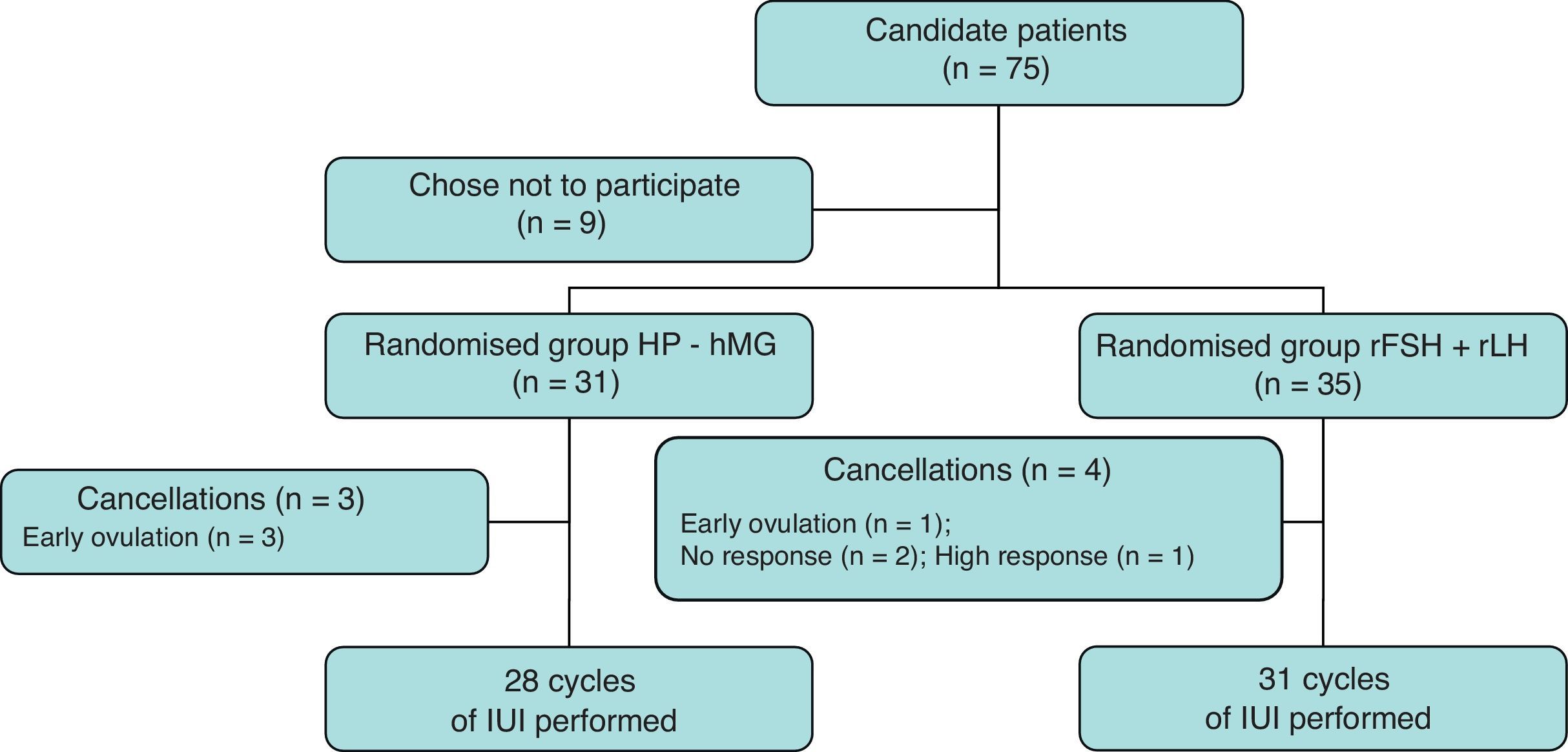

ResultsA total of 75 women were recruited for the study, of which 66 agreed to participate in it. Thirty-one patients were randomly assigned to group A (HP-hMG) and 35 patients to group B (rFSH+rLH). A total of 28 and 31 cycles of IUI were completed, respectively. Fig. 1 shows the flowchart of patients included.

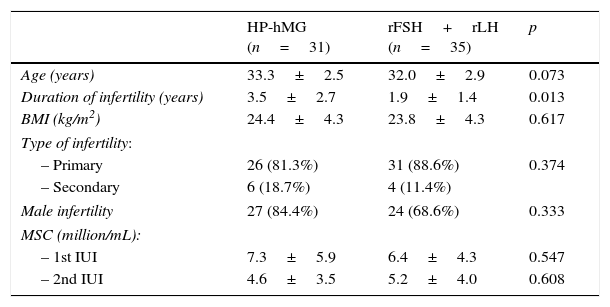

Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients included in both study groups. There were no significant differences in terms of the age of the patients and the percentage of cases of male factor infertility. Patients receiving HP-hMG exhibited infertility for a longer period of time than those receiving rFSH+rLH, with a statistically significant difference. Prepared semen samples used on both days were similar in the two study groups.

Baseline characteristics of patients included in the study.

| HP-hMG (n=31) | rFSH+rLH (n=35) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.3±2.5 | 32.0±2.9 | 0.073 |

| Duration of infertility (years) | 3.5±2.7 | 1.9±1.4 | 0.013 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.4±4.3 | 23.8±4.3 | 0.617 |

| Type of infertility: | |||

| – Primary | 26 (81.3%) | 31 (88.6%) | 0.374 |

| – Secondary | 6 (18.7%) | 4 (11.4%) | |

| Male infertility | 27 (84.4%) | 24 (68.6%) | 0.333 |

| MSC (million/mL): | |||

| – 1st IUI | 7.3±5.9 | 6.4±4.3 | 0.547 |

| – 2nd IUI | 4.6±3.5 | 5.2±4.0 | 0.608 |

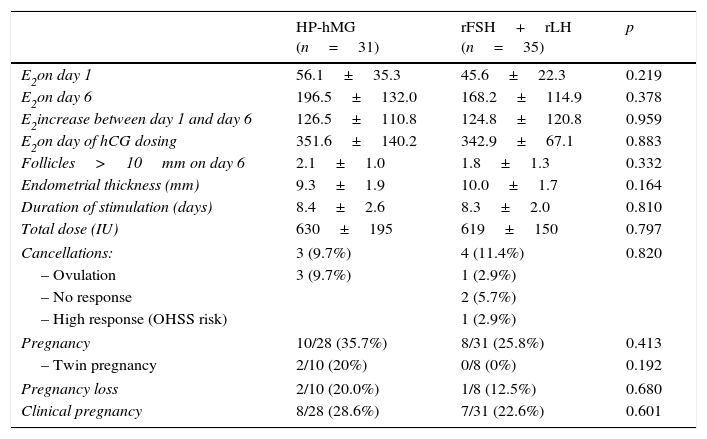

Table 2 shows the results of the cycle in terms of ovarian response and rate of cancellation, pregnancy, pregnancy loss and clinical pregnancy. No differences were observed in serum E2 increase between days 1 and 6 of stimulation, follicles recruited on day 6 (>10mm) and serum E2 on the day of administration of hCG. The duration of stimulation and total doses used were similar. No differences were observed in the rate and causes of cancellation. Pregnancy rates, pregnancy loss and clinical pregnancy between the two groups were similar.

Response to ovarian stimulation and clinical outcomes.

| HP-hMG (n=31) | rFSH+rLH (n=35) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E2on day 1 | 56.1±35.3 | 45.6±22.3 | 0.219 |

| E2on day 6 | 196.5±132.0 | 168.2±114.9 | 0.378 |

| E2increase between day 1 and day 6 | 126.5±110.8 | 124.8±120.8 | 0.959 |

| E2on day of hCG dosing | 351.6±140.2 | 342.9±67.1 | 0.883 |

| Follicles>10mm on day 6 | 2.1±1.0 | 1.8±1.3 | 0.332 |

| Endometrial thickness (mm) | 9.3±1.9 | 10.0±1.7 | 0.164 |

| Duration of stimulation (days) | 8.4±2.6 | 8.3±2.0 | 0.810 |

| Total dose (IU) | 630±195 | 619±150 | 0.797 |

| Cancellations: | 3 (9.7%) | 4 (11.4%) | 0.820 |

| – Ovulation | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | |

| – No response | 2 (5.7%) | ||

| – High response (OHSS risk) | 1 (2.9%) | ||

| Pregnancy | 10/28 (35.7%) | 8/31 (25.8%) | 0.413 |

| – Twin pregnancy | 2/10 (20%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0.192 |

| Pregnancy loss | 2/10 (20.0%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | 0.680 |

| Clinical pregnancy | 8/28 (28.6%) | 7/31 (22.6%) | 0.601 |

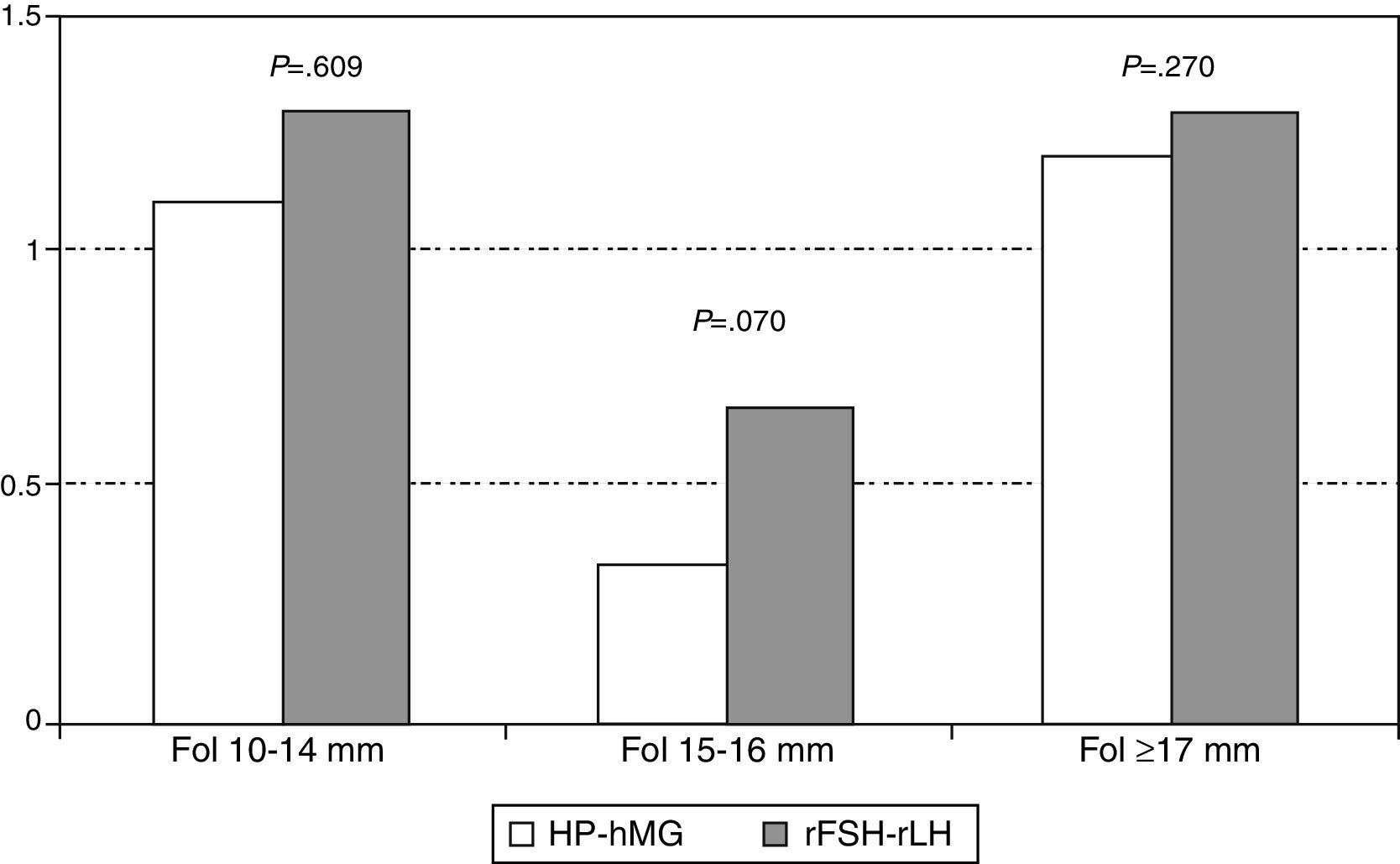

No statistically significant differences were observed in the distribution of mature (≥17mm), medium-sized (15–16mm) and small (10–14mm) follicles the day of hCG administration in both study groups. However, as shown in Fig. 2, the number of medium-sized follicles tended to be lower in the group receiving HP-hMG.

DiscussionThe main objective of this study was to evaluate the response to ovarian stimulation in IUI cycles when using HP-hMG as opposed to rFSH with rLH, in order to assess whether the bioactivity is comparable between the two treatments.

Our results show that ovarian response after 5 days of stimulation was almost identical in both groups, with an increase in serum E2 that also showed a very similar standard deviation, thereby reflecting a consistency between batches of HP-hMG comparable to that of the recombinant preparations. Recruitment was around 2 follicles with both protocols, which shows that both treatments are a valid option in intrauterine insemination, where a bifollicular response is considered appropriate and prudent to avoid an increased risk of multiple pregnancies.

Analysis of the response following stimulation also shows very close results in serum E2 and an even follicular distribution, although a slight tendency to the presence of a greater number of medium-sized follicles was observed in the group receiving rFSH+rLH. This trend did not reach statistical significance, probably because of the small sample size; it is in line, however, with an interesting study published about patients with WHO type II anovulation, which showed that HP-hMG reduces the number of medium-sized follicles and decreases the number of larger follicles without affecting the rates of clinical and ongoing pregnancy (Moro et al., 2015). A previous study published by Loumaye et al. (2003) had hypothesized that the LH activity is clinically relevant in the induction of ovulation in anovulatory patients because it facilitates selective follicular growth, decreasing the number of medium-sized follicles and increasing the proportion of women with a single dominant follicle (Loumaye et al., 2003). Similarly, in the context of IVF, it was observed that the addition of LH activity reduced the number of smaller follicles and increased the selection of larger ones (Filicori et al., 2001).

The decreased number of medium-sized follicles is of paramount clinical importance because it decreases the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation and multiple pregnancies, two of the complications to avoid in ovarian stimulation treatment for IUI. In our study, 2 cases of twin pregnancy were observed in the group receiving HP-hMG and one case was cancelled due to high ovarian response in the rFSH and rLH groups. With so few complications occurring, it is not possible to offer any conclusion in our study because they could be random.

The cancellation rate was also comparable for both protocols. There were 3 cases of cancellation due to spontaneous ovulation in the HP-hMG group, while the only cancellations due to low response (n=2) and risk of OHSS and multiple pregnancies (n=1) were in the group that received rFSH+rLH.

However, other larger studies found significant differences. In fact, it has been reported that the number of cancelled cycles and risk of OHSS and multiple pregnancies was significantly lower in the group receiving HP-hMG compared to the rFSH group (8.4% vs. 1.2%, respectively (absolute difference −7.27% (95% CI −11.3 to −3.7)) (Moro et al., 2015) or compared to the rFSH+rLH group in older patients (0.7% vs. 4.5%, OR: 6.73, P=0.013) (Loumaye et al., 2003).

In the descriptive analysis of the data, it is evident that the treatment groups did not differ in prognostic variables, such as age, BMI, type and severity of male factor infertility. It was only found that the group receiving HP-hMG suffered from longer-term infertility than the group receiving rFSH and rLH, with a statistically significant difference, but the magnitude of the difference does not appear to be clinically relevant (1.6 years).

The sample size of this study was calculated to assess ovarian response in terms of serum E2 increase between the first day of stimulation and after 5 days of treatment. This value was chosen as the most relevant, since it is the most objective assessment possible and can indirectly reflect follicular dynamics. The number of recruited follicles (>10mm) at the same time of the cycle was chosen as an additional parameter. Secondly, serum E2 and the distribution of follicular growth at the end of stimulation were compared, on the day of hCG administration.

However, with this sample size, the statistical power to estimate clinical outcomes is insufficient. In any case, the data obtained show rates of clinical pregnancy, miscarriage and ongoing pregnancy that are comparable between both groups. These clinical results are expected, since both demographic and prognostic characteristics of patients, ovarian response and semen parameters were similar.

When our study was conducted and preliminary data were presented at the congress of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) (Labarta et al., 2007), no published studies so far had compared the effectiveness of both protocols in intrauterine insemination maintaining the same FSH:LH activity ratio of 1:1. Recently, a study has been published comparing the efficacy of HP-hMG and rFSH+ rLH in a ratio of 1:1 in women over 35 years undergoing IUI treatment. The difference between this work and ours is that the doses are 75IU/day vs. 150IU/day, respectively. Moreover, the mean age of our patients was significantly lower. However, both studies obtained consistent conclusions, because they suggest that the bioactivity of HP-hMG is similar to that provided by the combination of rFSH+rLH when administered in the same ratio.

Consequently, we believe that the use of HP-hMG in inducing ovulation is a very useful option considering that, while obtaining the same results, it can reduce the risk of multiple pregnancies and ovarian hyperstimulation. This effect is evident in young patients, such as those in our study, as well as in older patients, as has been recently published. In any case, in order to evaluate differences in clinical outcomes, further prospective RCT studies including a larger number of women should be planned.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.