Despite the number of research studies regarding the individual burden of migraine, few studies have examined its impact on the patients’ partners. We aim to assess migraine effects on the patients’ partners on sentimental relationship, children relationship, friendship, and work, as well as the caregiver burden, anxiety and/or depression.

MethodsA cross-sectional observational study was conducted through an online survey of partners of patients with migraine followed-up in 5 Headache Units. Questions about the 4 areas of interest and 2 scales (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Zarit scale) were included. Scores were compared against the population prevalence.

ResultsOne hundred and fifty-five answers were analysed. Among the patient’s partners 135/155 (87.1%) were men, with a mean age of 45.6 ± 10.1 years. Migraine’s main effects on partners were observed in the sentimental relationship and items concerning children and friendships, with a minor impact at work. Partners showed a moderate burden (12/155 = 7.7% [4.1%–13.1%]), and a higher moderate-severe anxiety rate (23/155 = 14.8% [9.6%–21.4%]), and similar depression rate (5/155 = 3.2% [1.1%–7.3%]) compared to the National Health Survey.

ConclusionsThe burden of migraine impacts the partners’ personal relationship, childcare, friendship and work. Moreover, certain migraine partners showed a moderate burden according to Zarit scale and higher anxiety levels than the Spanish population.

Diversos estudios han evaluado la sobrecarga individual de la migraña, sin embargo, pocos estudios han examinado su impacto en las parejas de los pacientes. Nuestro objetivo es evaluar los efectos de la migraña en las parejas de los pacientes sobre la relación sentimental, la relación con los hijos, la amistad y el trabajo, así como la sobrecarga del cuidador, la ansiedad y/o la depresión.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio observacional transversal a través de un cuestionario en línea a las parejas de pacientes con migraña seguidos en cinco Unidades de Cefalea. Se incluyeron preguntas sobre las cuatro áreas de interés y dos escalas (Escala de Ansiedad y Depresión Hospitalaria y escala de Zarit). Las puntuaciones se compararon con la prevalencia de la población según la Encuesta Nacional de Salud.

ResultadosSe analizaron ciento cincuenta y cinco respuestas. Las parejas de los pacientes con migraña fueron 135/155 (87.1%) hombres, edad media de 45.6 ± 10.1 years; Los principales efectos de la migraña en la pareja se observaron en la relación sentimental y en los ítems relativos a los hijos y las amistades, con menor impacto en el trabajo. Las parejas mostraron una carga moderada (12/155 = 7,7%[4,1%-13,1%]), y una tasa de ansiedad moderada-grave más alta (23/155 = 14,8%[9,6%-21,4%]) y una tasa de depresión similar (5/155 = 3,2%[1,1%-7,3%]) respecto a la población española.

ConclusionesLa carga de la migraña tiene un impacto en la relación personal de la pareja, el cuidado de los hijos, la amistad y el trabajo. Además, algunos cuidadores de pacientes con migraña presentan una carga moderada y niveles de ansiedad más altos que la población española.

Migraine is a stigmatised disease which entails prejudice and stereotypes that may lead to worsening of health status and personal relationships, and to unemployment or social status decline.1,2 Currently, one of the main aspects on which clinical trials are focusing is patient-reported outcomes,3 which has been found to be an important issue for patients with migraine.4 Some studies have addressed the family impact of migraine, such as the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes study (CaMEO).5–7 However, the partner’s opinion, knowledge and involvement concerning migraine have barely been studied. Due to the chronic nature of the disease, the unpredictability of the attacks and its clinical characteristics, which produce isolation with a direct impact on the patients’ social and/or family life, the disease’s real impact could be greater than has previously been described. Migraine may significatively impact the patient’s partner’s lifestyle and could entail caregiver burden, as well as a higher prevalence of mood disorders than the average population. The hypothesis of this study is that migraine may have a substantial impact on the daily life of migraine patients’ partners, including potential mental health disorders and burden related to the patients’ care. Therefore, we aim to analyse migraine’s effect on the patient’s partner in 4 areas: couple relationship, relationship with their children, friendship, and impact at work; as well as to evaluate the caregiver burden and the presence of symptoms of depression and anxiety among them.

MethodsStudy population and data collectionThis is a cross-sectional observational study that was conducted in 5 Headache Units from 5 third-level hospitals. The patients with migraine were being followed up during the recruitment period at any of the mentioned Headache Units and were contacted via a telephone call to invite them and their partners to participate in the study. Then, these participants received an email with a link to an online survey where filling consent to participate in the study was mandatory to be included. The online survey was anonymously filled by migraine patients’ partners between 8 June and 8 October, 2020, through Google Forms. The following items were registered: sex, age, migraine progression time, migraine classification (episodic or chronic), prescribed treatment and current treatment, time spent together at home, impact on couple relationship, impact on the relationship with the children, friendship impact, and work impact. For the survey’s implementation, the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) official guide to communicate results of Internet surveys was followed.8 The survey was voluntary, its estimated duration was shown at the beginning of the survey, there was no randomisation of the items, and some questions could be answered exclusively depending on previous answers (eg, questions related to the children). The survey (which included open and yes/no questions) can be consulted in the Supplementary Material. Only the first 2 authors and the last author had access to the data, without access to personal details that could allow the identification of subjects.

The inclusion criteria for patients were: 1) age between 18 and 65 years, 2) episodic or chronic migraine diagnosis following the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-III),9 and 3) being diagnosed for at least 6 months; the inclusion criteria for partners were: 1) age between 18 and 65 years and 2) at least one-year of sentimental relationship with the patient. Patients’ exclusion criteria were: 1) primary or secondary headache (different to migraine) diagnosis, except for medication-overuse headache or infrequent tension-type headache (less than one day per month), 2) neurological, psychiatric, or incapacitating diseases diagnosis, and 3) another syndrome accompanied by pain. Partners’ exclusion criteria were: 1) not having enough cognitive ability to complete the survey, having refused informed consent, 3) cohabitating with the patient less than 3 days per week, and 4) suffering from migraine (at least one crisis per month), another syndrome accompanied by pain or neurological, psychiatric, or incapacitating diseases diagnosis.

Partnerss burden concerning the patient’s care was analysed according to the Zarit scale.10 This scale includes 22 items, with 5 options each, scoring between 0 and 4, being 0 = never and 4 = nearly always. The categorical scores for caregiver burden are no burden (score lower than 22), mild (score between 22 and 40, both included), moderate (score between 41 and 60, both included), and severe (score higher than 60). Anxiety and depression levels on the partner were analysed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).11 This scale has 7 questions concerning anxiety and another 7 concerning depression. Depending on the answer, each question scores between 0 and 3, with 4 possible answers. The 4 possible categorical scores are normal (score lower than 8), mild (score between 8 and 10, both included), moderate (score between 11 and 14, both included) and severe (score higher than 14).

Study endpointsThe primary endpoint was to evaluate the effect of cohabitating with migraine patients on the 4 areas (sentimental relationship, relationship with children, friendship, and work impact). Secondary endpoints were partners’ levels of anxiety and depression measured by HADS scale and partner’s burden according to the Zarit scale.

Statistical analysisThe descriptive analysis of the quantitative (ratio) variables was conducted with mean and standard deviation (SD). The qualitative variables (nominal and ordinal) were described by frequency and their percentage. Binomial tests were used to evaluate the effect of cohabiting with migraine patients on the 4 areas (sentimental relationship, relationship with children, friendship, and work impact), anxiety, depression, and burden appearance. For this assessment, there is no specific hypothesis test and only the proportion and the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated. With respect to anxiety and depression, both percentages were compared, according to the HADS scores (moderate or severe values), to the global Spanish prevalence shown in a national mental health study conducted by the Spanish Department of Health in 2017, which was 6.7% for both disorders.12 With regard to patients’ partners’ burden, it was studied whether the proportion of partners with moderate or severe scores was significatively different from 0 or not. To evaluate factors weighing on anxiety, depression and burden appearance, univariate models like generalised linear models (GLM) with Gaussian family were made so as to establish the candidate variables to a later analysis with models with multiple covariates (variables with P < .2).

Once the variables were selected, GLM with multiple covariates were obtained following a stepwise strategy, ie, a variable could be added or removed in every step. Models were chosen according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC), with the lowest value representing the best model.13 Once every model was obtained, collinearity between variables was verified, suppressing those with higher variance inflation factor (VIF), and repeating the procedure when co-linearity was found. Statistical significance was established as P < .05. Every analysis was made with the R statistical software, version 3.5.2, and the selected predictors included in the final models were corrected by multiple comparisons with the false discovery rate (FDR) method developed by Benjamini and Hochberg.14

Furthermore, as secondary analysis, the relationship between scales was studied with the Pearson correlation value. The consistency of the obtained measures was verified with Cronbach’s alpha. To obtain a 95% CI for the Cronbach’s alpha, 1000 bootstrap samples were used (for this sole aim). Complete case analysis was carried out in case of missing data.

Ethical approvalThe study followed the basic ethical principles described in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Rules of Good Clinical Practice (CPMP/ICH/135/95) getting approval by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario de la Princesa (number 4090).

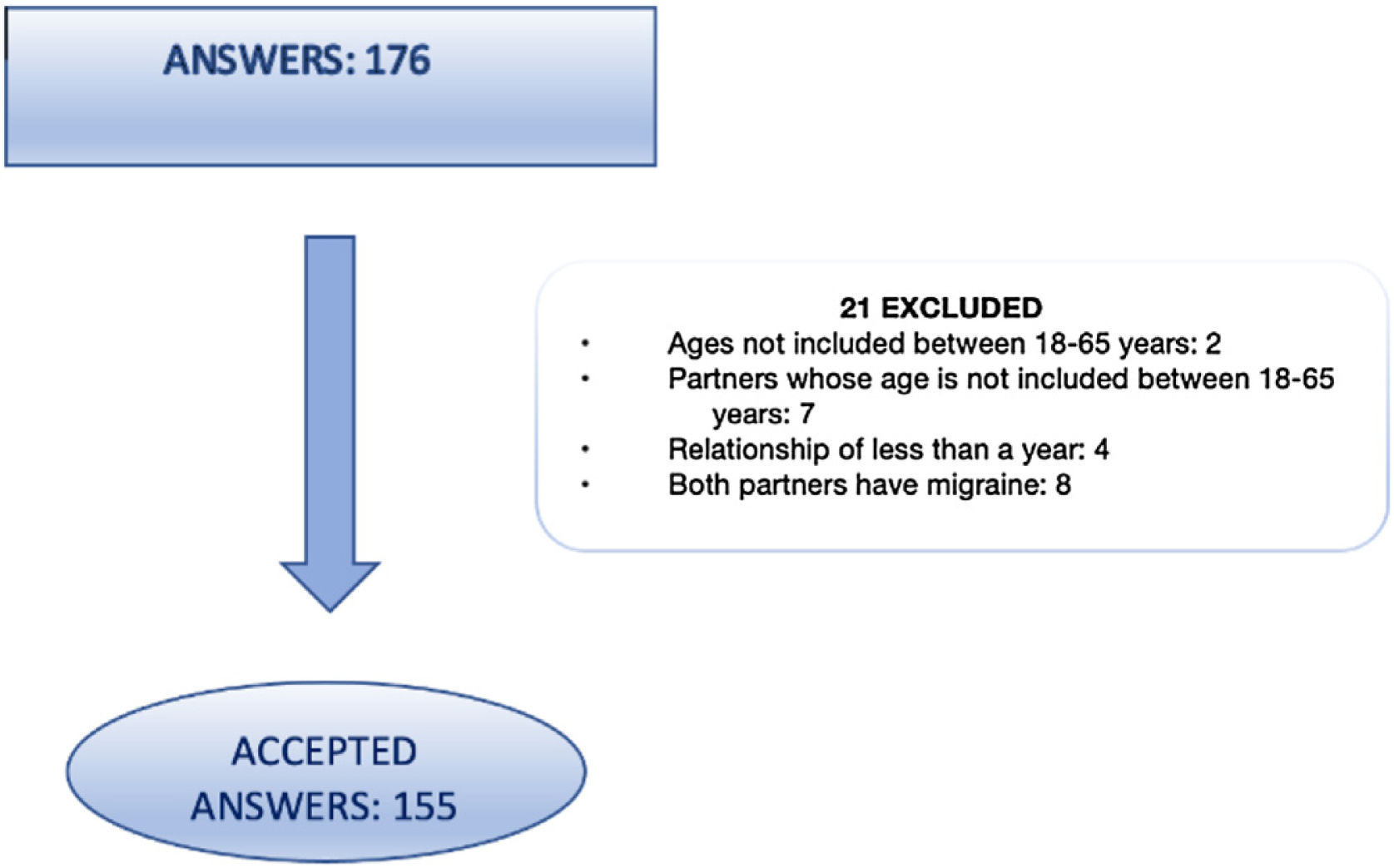

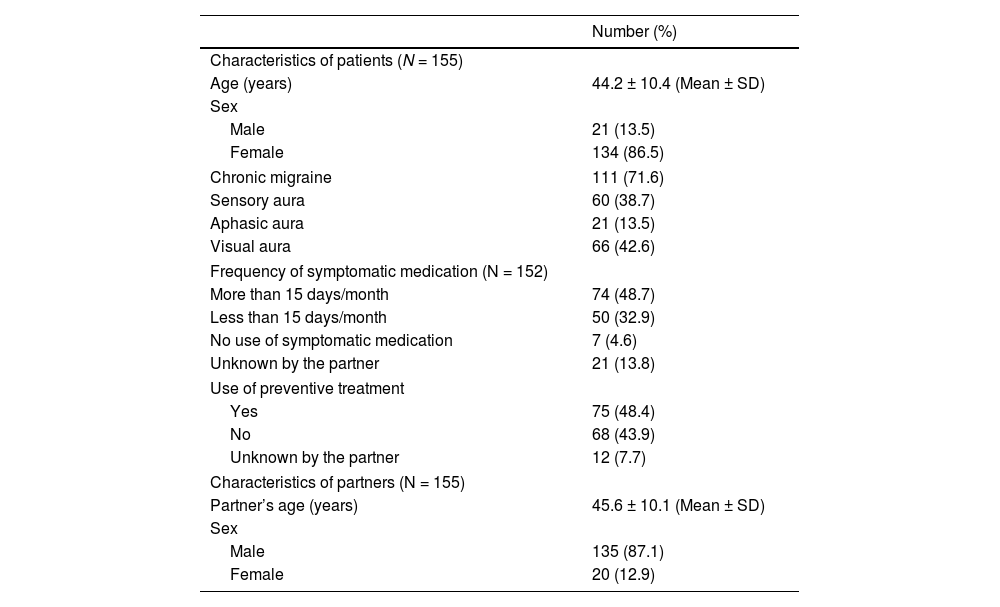

ResultsA total of 176 answers were collected, 155 of which fulfilled eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the main characteristics of patients and their partners. Among the patient’s partners 135/155 (87.1%) were men, with a mean age of 45.6 ± 10.1 years; patients were women in 134/155 (86.5%) cases, with a mean age of 44.2 ± 10.4 years; 111/155 (71.6%) suffered from chronic migraine; other characteristics of the patients and their partners can be consulted in Tables S1−3.

Characteristics of patients and partners.

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Characteristics of patients (N = 155) | |

| Age (years) | 44.2 ± 10.4 (Mean ± SD) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 21 (13.5) |

| Female | 134 (86.5) |

| Chronic migraine | 111 (71.6) |

| Sensory aura | 60 (38.7) |

| Aphasic aura | 21 (13.5) |

| Visual aura | 66 (42.6) |

| Frequency of symptomatic medication (N = 152) | |

| More than 15 days/month | 74 (48.7) |

| Less than 15 days/month | 50 (32.9) |

| No use of symptomatic medication | 7 (4.6) |

| Unknown by the partner | 21 (13.8) |

| Use of preventive treatment | |

| Yes | 75 (48.4) |

| No | 68 (43.9) |

| Unknown by the partner | 12 (7.7) |

| Characteristics of partners (N = 155) | |

| Partner’s age (years) | 45.6 ± 10.1 (Mean ± SD) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 135 (87.1) |

| Female | 20 (12.9) |

SD: Standard deviation.

Regarding sentimental relationship, 3 variables showed a proportion over 50% in patient’s partners: change of the own routine as consequence of migraine attacks (120/154 = 77.9%; 95% CI: 70.5%-84.2%), increased amount of housework because of migraine (96/152 = 63.2%; 95% CI: 55.0%-70.8%), and the belief that the relationship with the patient would be better without migraine (105/139 = 75.5%; 95% CI: 67.5%-82.4%). On the other hand, self-perceived distance from the patient because of migraine (47/149 = 31.5%; 95% CI: 24.2%-39.7%), lower trust in the patient (12/146 = 8.2%; 95% CI: 4.3%-13.9%), and a larger number of arguments due to migraine attacks (51/151 = 33.8%; 95% CI: 26.3%-41.9%) presented a low proportion (lower than 50%).

In the evaluation of the relationship with their children, a sole variable, fear that children would suffer from migraine (81/132 = 61.4%; 95% CI: 52.5%-69.7%), presented a proportion over 50%. The other variables can be checked in the Supplementary Material.

With respect to friendship, the variable related to cancelling plans with friends due to migraine attacks showed a proportion over 50% (110/151 = 72.8%; 95% CI:65.0%-79.8%) and partners of patients judged that they had more social relationships than their partner with a low proportion (19/147 = 12.9%; 95% CI: 8.0%–19.4%).

Concerning the impact on the workplace, a low proportion was found in 3 variables: worse job performance related to the patient’s attacks (12/149 = 8.1%; 95% CI: 4.2%–13.6%), change of employment related to migraine (5/155 = 3.2%; 95% CI: 1.5%–7.4%), and difficulties combining work and love life because of migraine attacks (26/151 = 17.2%; 95% CI: 11.6%-24.2%).

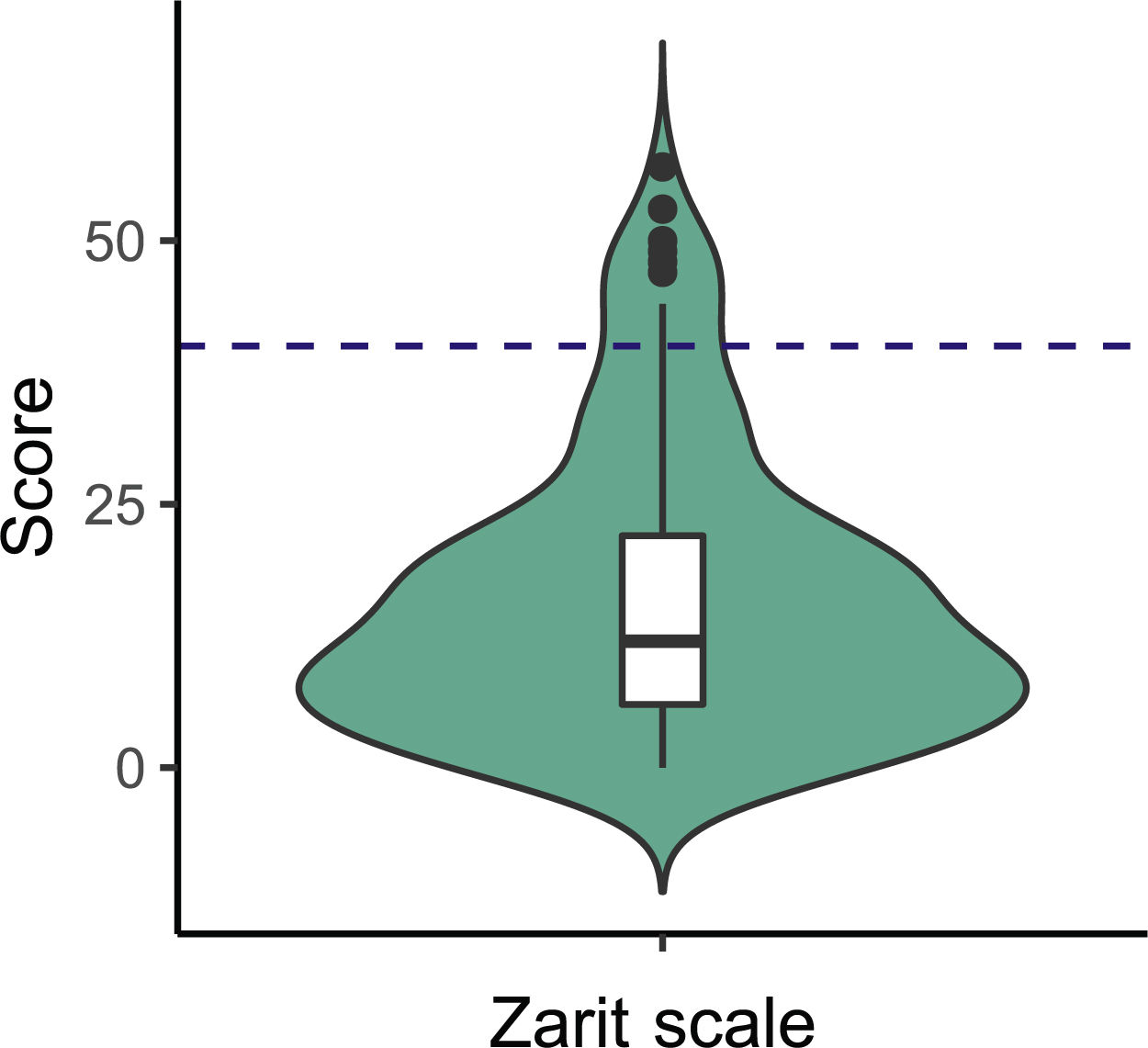

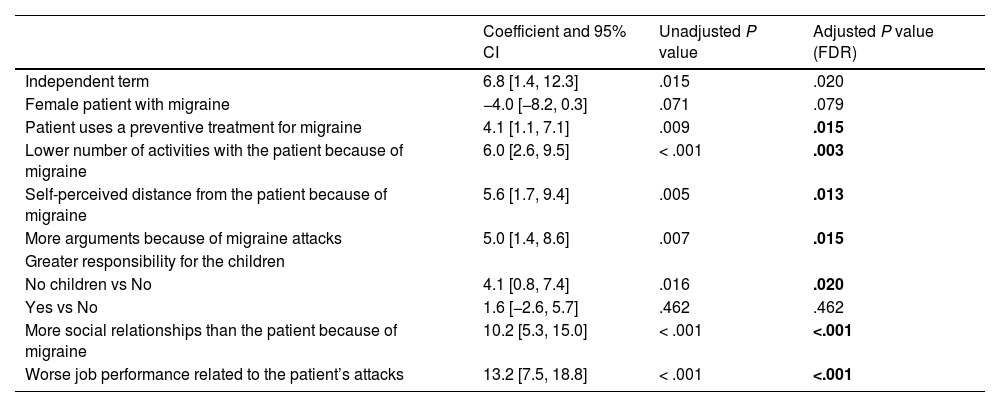

Caregiver burdenThe number of partners that presented moderate burden according to the Zarit scale was between 4%-13% (12/155 = 7.7%; 95% CI: 4.1%–13.1%); further details are available in Table S4. Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.93 [0.91–0.94], which denotes high consistency. Fig. 2 shows the scores’ distribution. After applying FDR correction, it was observed that statistically significant higher burden scores according to the Zarit’s scale were associated with use of preventive treatment (adjusted P = .015). Moreover, higher Zarit’s scale scores were associated with the following daily life situations: lower number of activities (adjusted P = .003), self-perceived distance from the patient (adjusted P = .013), and more arguments because of migraine attacks (adjusted P = .015). With reference to the variables related to the relationship with the children, higher burden scores were identified in people with no children with respect to those who did not feel more responsibility regarding their care (adjusted-P = .020). Higher values in the Zarit scale were linked to a higher number of social relationships than the patient due to migraine (adjusted P < .001) and worse job performance related to the patient’s attacks (adjusted P < .001). The complete results of the analysis are shown in Table 2. Univariate analysis results can be consulted on Table S5.

Generalised linear model with multiple covariates for the Zarit scale in the respondents.

| Coefficient and 95% CI | Unadjusted P value | Adjusted P value (FDR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent term | 6.8 [1.4, 12.3] | .015 | .020 |

| Female patient with migraine | −4.0 [−8.2, 0.3] | .071 | .079 |

| Patient uses a preventive treatment for migraine | 4.1 [1.1, 7.1] | .009 | .015 |

| Lower number of activities with the patient because of migraine | 6.0 [2.6, 9.5] | < .001 | .003 |

| Self-perceived distance from the patient because of migraine | 5.6 [1.7, 9.4] | .005 | .013 |

| More arguments because of migraine attacks | 5.0 [1.4, 8.6] | .007 | .015 |

| Greater responsibility for the children | |||

| No children vs No | 4.1 [0.8, 7.4] | .016 | .020 |

| Yes vs No | 1.6 [−2.6, 5.7] | .462 | .462 |

| More social relationships than the patient because of migraine | 10.2 [5.3, 15.0] | < .001 | <.001 |

| Worse job performance related to the patient’s attacks | 13.2 [7.5, 18.8] | < .001 | <.001 |

Sample size was N = 155. When a reference is not explicitly shown for a variable, the reference is the corresponding negative or opposite feature (eg, lower number of activities vs no lower number of activities). For the first variable excluding the independent term, the reference category is male patient. The independent term reflects the value of the Zarit scale when all variables for a subject present the reference category. The FDR correction was only applied to the variables included in this model. Statistically significant results are shown in bold.

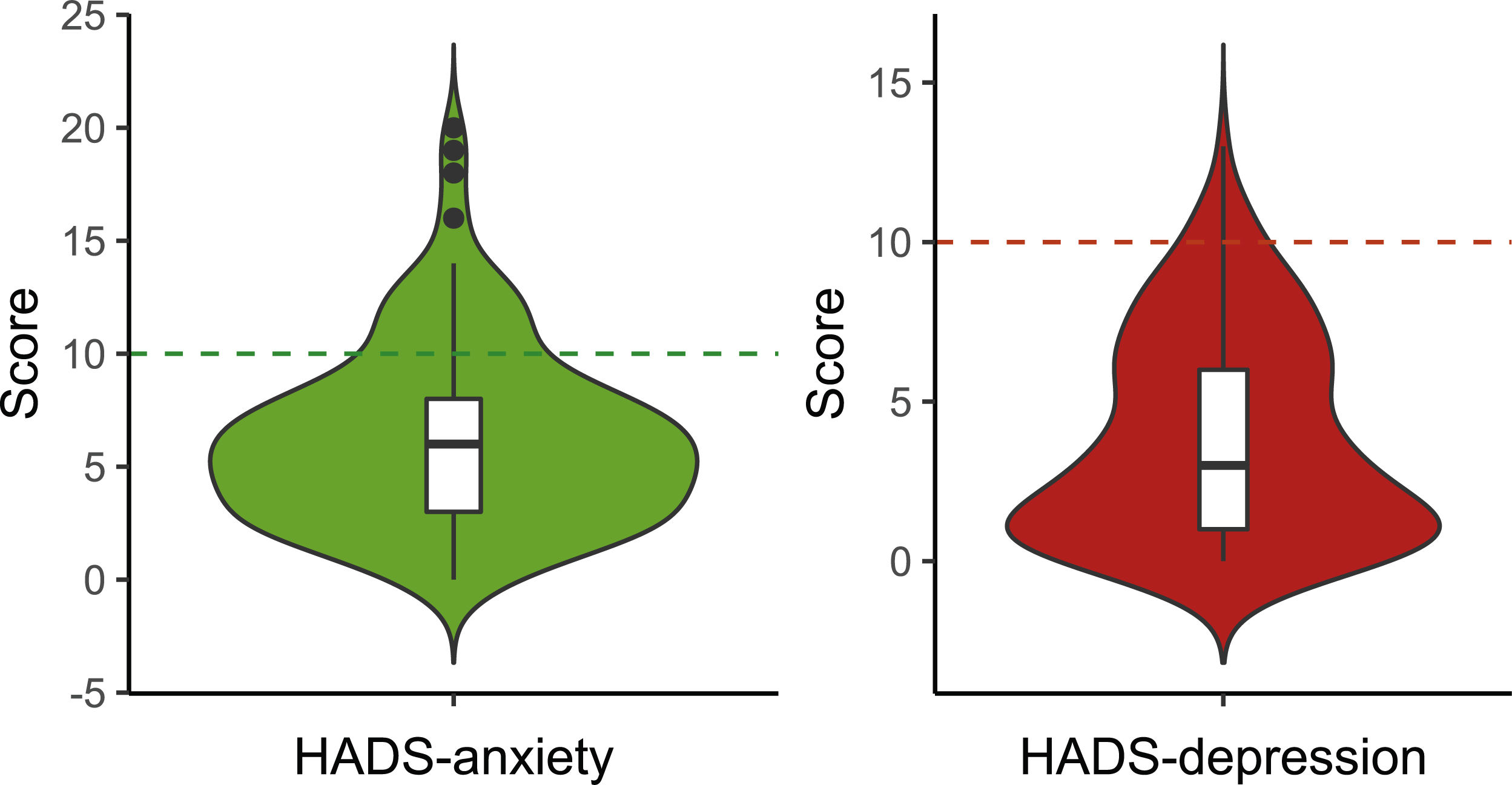

In relation to HADS anxiety subscale, partners presented a higher proportion of moderate-severe anxiety with respect to the Spanish national prevalence of 6.7% (23/155 = 14.8%; 95% CI: 9.6%-21.4%). With higher detail, men over 44 showed no statistically significant differences of moderate-severe anxiety compared to the Spanish prevalence of this group, ie, 3.3%-6.2% (5/73 = 6.8%; 95% CI: 2.3%-15.6%), while men under 45 showed significantly higher proportion of moderate-severe anxiety than the national maximum prevalence for any age group, ie, 6.2% for men between 45 and 54 (9/62 = 14.5%; 95% CI: 6.9%-25.8%). Women presented higher proportion of moderate-severe anxiety than the national maximum prevalence for any group, ie, 13.4% for women between 55 and 64 (9/20 = 45.0%; 95% CI: 23.1%-68.5%). Regarding the depression subscale, the proportion of partners with moderate depression showed no statistically significant differences compared to the Spanish national prevalence of 6.7% (5/155 = 3.2%; 95% CI: 1.1%-7.3%) but did not achieve statistically significant differences; further details are available in Table S4. The 95% CI includes the prevalence of depression for men in any age group and the prevalence for women younger than 55 years. Cronbach alpha score for each scale was α = 0.85 [0.80-0.89] in anxiety (high consistency) and α = 0.77 [0.71-0.82] in depression (good consistency). Fig. 3 shows the distribution for anxiety and depression scores.

Violin plots accompanied by box and whiskers plots showing the distribution of the anxiety (left) and depression (right) HADS subscale scores of the participants. The green and red dotted lines represent the threshold between mild and moderate levels of anxiety and depression, respectively (the maximum score for mild levels is 10 in both subscales).

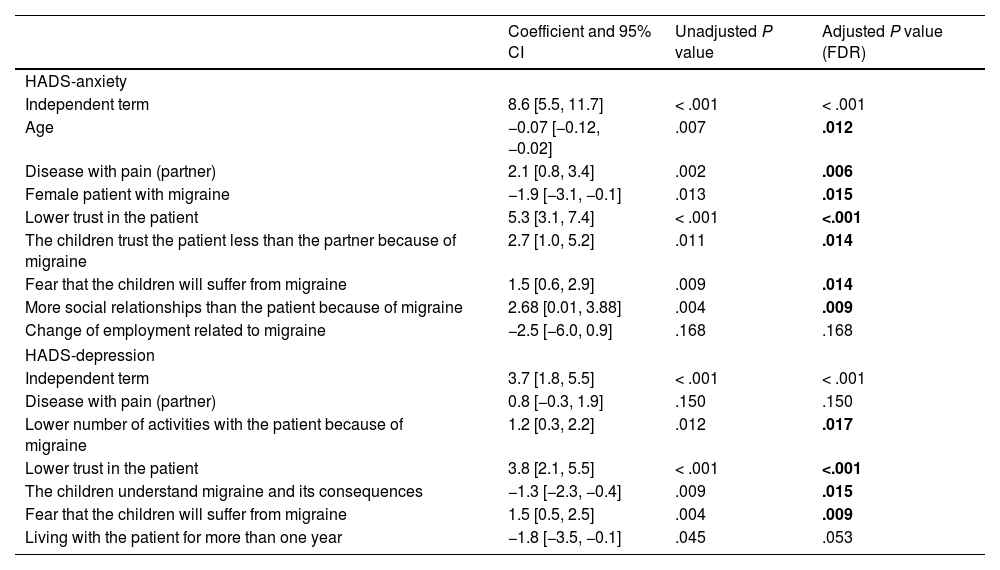

According to our results, higher anxiety levels in the partners of patients with migraine were related to age, sex of the patient, suffering from a disease accompanied by pain, and specific variables associated with daily life situations, relationship with the children and social relationships. Once FDR correction was applied to anxiety subscale, it was observed that higher scores in the scale were associated with the partner’s having a disease with pain different to migraine (adjusted P = .006) and, regarding daily life situations, presenting lower trust in the patients (adjusted P < .001). Lower anxiety scores were associated with a higher age (adjusted P = .012) and cohabiting with a female patient with migraine (adjusted P = .015). Regarding the relationship with the children, higher anxiety values were associated with lower trust in the patient by the children because of migraine (βadjusted P = .014) and fear of future migraine in children (adjusted P = .014). Moreover, higher values were identified in the partners with more social relationships than the patient (adjusted P = .009).

In the case of the depression subscale, higher depression levels were linked to particular daily life situations and variables reflecting aspects of the relationship with the children. After FDR correction was applied, higher values of depression were related to lower trust in the patient (adjusted P < .001) and lower number of activities with the patient because of migraine (adjusted P = .017). Higher values were associated with the fear that the children will suffer from migraine (adjusted P = .009). In contrast, the fact that children understand migraine and its consequences showed lower values related to depression (adjusted P = .015). Complete results of the analysis with multiple covariates are reflected in Table 3. Univariate analysis results can be consulted in Tables S6−7.

Generalised linear model with multiple covariates for the HADS anxiety and depression scores in the respondents.

| Coefficient and 95% CI | Unadjusted P value | Adjusted P value (FDR) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HADS-anxiety | |||

| Independent term | 8.6 [5.5, 11.7] | < .001 | < .001 |

| Age | −0.07 [−0.12, −0.02] | .007 | .012 |

| Disease with pain (partner) | 2.1 [0.8, 3.4] | .002 | .006 |

| Female patient with migraine | −1.9 [−3.1, −0.1] | .013 | .015 |

| Lower trust in the patient | 5.3 [3.1, 7.4] | < .001 | <.001 |

| The children trust the patient less than the partner because of migraine | 2.7 [1.0, 5.2] | .011 | .014 |

| Fear that the children will suffer from migraine | 1.5 [0.6, 2.9] | .009 | .014 |

| More social relationships than the patient because of migraine | 2.68 [0.01, 3.88] | .004 | .009 |

| Change of employment related to migraine | −2.5 [−6.0, 0.9] | .168 | .168 |

| HADS-depression | |||

| Independent term | 3.7 [1.8, 5.5] | < .001 | < .001 |

| Disease with pain (partner) | 0.8 [−0.3, 1.9] | .150 | .150 |

| Lower number of activities with the patient because of migraine | 1.2 [0.3, 2.2] | .012 | .017 |

| Lower trust in the patient | 3.8 [2.1, 5.5] | < .001 | <.001 |

| The children understand migraine and its consequences | −1.3 [−2.3, −0.4] | .009 | .015 |

| Fear that the children will suffer from migraine | 1.5 [0.5, 2.5] | .004 | .009 |

| Living with the patient for more than one year | −1.8 [−3.5, −0.1] | .045 | .053 |

Sample size was N = 155. When a reference is not explicitly shown for a variable, the reference is the corresponding negative or opposite feature (eg, disease with pain vs no disease with pain). The reference category for the female patient variable is living with a male patient. The reference for age is 0 years. The independent term reflects the value of the HADS scales when all variables for a subject present the reference category. The FDR correction was only applied to the variables included in each model. Statistically significant results are shown in bold.

Correlation between scales was analysed, obtaining a moderate correlation in all cases: between Zarit and anxiety-HADS scales r = 0.53 (0.40-0.63) (Fig. S1); between Zarit and depression-HADS scales r = 0.59 (0.47-0.68) (Fig. S1); between anxiety and depression HADS r = 0.70 (0.61-0.77) (Fig. S1).

DiscussionThe present study shows that migraine substantially influences partners’ lifestyle, mainly in aspects related to daily life, social relationships, and the relationship with the children, and causes a moderate caregiver burden in a proportion of the partners of the patients, also generating higher levels of anxiety in comparison to the general population, with scarce impact on the depression levels.

Migraine’s repercussion on the patients’ partners’ lifestyleIt has been reported that migraine is the leading cause of years lived with disability between 15 and 49 years.15 In this study, it is shown that migraine not only affects patients but also worsens the quality of life of their partners or relatives. These results are in line with the Eurolight study, in which a meaningful proportion of patients with migraine declared that headaches caused difficulties in their love life, including the loss of social activities by the partner, and prevented the patients from caring their children.16 Similar results were reported in the Atlas of Migraine conducted in Spain in 2018, a survey for Spanish patients and their families. In addition, most patients with chronic or episodic migraine identified repercussions on all studied areas (change of employment, going outside so there was silence, lost friendships, playing with their children, and impossibility to make any plans, among others).17 Moreover, in a study that involved adolescents (11–17 years old) and children of a parent with migraine, it was found that migraine especially affected childrens’ global well-being and their relationship with their parents.18

Our study has pointed out that migraine notoriously influences the patient’s partner’s life in 3 out of the 4 studied areas: couple relationship, relationship with friends and with their children. However, work impact was limited, just as poorer work performance, and the need to change jobs, exceptionally. We found that partners were influenced by their relatives’ migraine attacks, which may force them to change their routines, plans with friends and/or the amount of housework to do. These changes are of great relevance and partners claimed that their relationship would be better if the patient did not suffer from migraine. The different areas of day life affected by migraine would favour both anxiety and depression, as well as the feeling of having to take care of their partner. To sum up, our study’s results suggest that patients’ partners are influenced by migraine with a substantial impact on their lives; therefore, patients may be aware of this repercussion on their families’ lives, which could explain part of the stigma associated with migraine.2

Burden on patients’ partnersThis study is the first to show that migraine is a disease that could overburden the patients’ partners. Using the Zarit scale as a burden measure, despite not being specifically designed for migraine, 7.7% of partners (with an average score of 16.1) presented moderate burden. These values are lower than those of the same Zarit scale in other neurological conditions.19–23 In the case of epilepsy (score of 20 points) some similarities with migraine must be noted: the disease manifests as attacks, and the symptoms’ similar age of onset concerning its stigma.24 This overburden, although occurring in less than 10%, might be interesting due to migraine being considered one of the most disabling neurological disease in terms of disability-adjusted life years standardised by age,25 which could explain the presence of a burden scores in their partners. Moreover, it would be interesting to design a Zarit based scale for partners of patients to improve the measurement of the burden of the disease; moreover, it would be interesting to study if caregiver burden increases with disease progression, if it keeps stable, or even if it decreases when patients have a good adherence to treatment permitting a proper control of the crisis.

Anxiety and depression in the patients’ partnersWe found that moderate-severe anxiety prevalence (14.8%) was higher than the Spanish population’s value (6.7%), particularly in men under 45 and in women. Moderate depression prevalence in the studied partners presented a similar proportion compared to the Spanish population (6.7%), according to values provided by the National Health Survey conducted by the Spanish Health Department in 2017.12

Anxiety has already been described in caregivers of patients suffering from other neurological diseases, such as epilepsy, using the Hamilton scale for anxiety,26 or dementia, in which a meta-analysis of 10 studies showed an anxiety prevalence of 32.1%,27 higher than therate observed in migraine patients’ partners. However, it must be noted that dementia involves a greater dependence and that, in the study conducted on Spanish population, 79.2% of caregivers were women, who suffer from higher mood disorders prevalence.28 In the current study 87.1% of patients’ partners were men, which makes migraine an important factor for anxiety in couple relationships.

Lower scores in the depression subscale were associated with the children’s understanding of the illness and its consequences. A similar effect has already been described in another interventional study, regarding anxiety and stress levels suffered by epilepsy patients’ caregivers, with reduced anxiety and stress levels in the caregiver group that attended informative sessions (about the disease, treatment, etc).29 Therefore, the understanding of the disease and its consequences by the family could be considered a protective factor regarding mood disorders, and it could help diminish the disease’s impact on the family.

Limitations of the studyThe study has several limitations: only patients from Headache Units were offered to participate to assure a proper understanding of the study, therefore it implies a selection bias; moreover, there was no matched control group; in addition, we were unable to study the possible correlation between the results of the survey and the medical history of the patients with migraine; lastly, the worldwide epidemiological situation could have had an impact in the present study.

ConclusionsMigraine is a disease which involves a meaningful impact not only for the patients, but also for their partners, especially affecting their sentimental relationships and relationships with their children and their friends. It has been observed that partners of patients with migraine present higher anxiety levels than the average population. Furthermore, it has been shown that migraine may imply a moderate caregiver burden, similar to the burden caused by other neurological diseases.

As far as we know, this is the first study focused on the repercussion of migraine patients’ partners. This broadens the knowledge about the psychosocial repercussion of migraine in its environment and emphasises the need to implement partner’s approach and tailored questionnaires when evaluating a patient with migraine to help diminish the stigma of this disease.

Key findings- •

Migraine has an impact on patients’ partners, especially affecting their sentimental relationships, their children, and their friends.

- •

Higher anxiety levels than the average population were found in partners of patients with migraine.

- •

Migraine partners show a moderate burden, similar to other neurological diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, epilepsy or multiple sclerosis.

Any data that support the findings of this study are included within the article.

FundingFunding ISCIII & European Union (ESF), Río Hortega Fellowship (CM21/00178) to AGM”. ALG was supported by the European Union (NextGenerationEU).

Competing interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest in this article.

Ethical approvalThe study obtained the approval of the Medical Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario de la Princesa (register number 4090).

Informed consentPrior to the inclusion in the study, participants signed the informed consent and there was no economical compensation regarding the participation in the study.

We thank AEMICE (Spanish Migraine and Headache Association) for their support and advice when providing the patient's perspective for this study.