Delayed post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy (DPHL) is a rare condition that may manifest after a prolonged period of cerebral hypoxia.

We present the case of a 43-year-old man who was found unconscious at his home. Examination revealed generalised muscle rigidity, miotic pupils, lack of response to stimuli, and a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3. He initially responded to intravenous naloxone, but significant respiratory effort persisted, with tachypnoea, tachycardia, and diffuse rhonchi on auscultation. Despite receiving oxygen at an FiO2 of 100%, and nebulised salbutamol and ipratropium bromide, the patient developed acute respiratory failure, requiring orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. He presented low-grade fever, and a chest radiography revealed consolidations at both lung bases; the results of a cranial CT scan and a blood test were normal. A urine test revealed presence of benzodiazepines, opioids, and cannabis. His personal history included paranoid schizophrenia, beginning in adolescence and treated with olanzapine and amisulpride. He also occasionally consumed opioid and sedative drugs, cannabis, and cocaine.

Two days after admission, his level of consciousness recovered; a neurological examination yielded normal results. As a complication, the patient developed a respiratory infection, which responded well to antibiotics, and acute renal damage secondary to an increased level of creatine kinase (8277U/L), due to probable rhabdomyolysis. Twenty-one days after admission, his condition suddenly worsened, with the development of somnolence and bradypsychia. He progressively began to present stereotypic movements, motor disinhibition, and reduced verbal communication, with diminished fluency and impaired comprehension. All limbs presented cogwheel rigidity. Myotatic reflexes were normal and plantar reflexes were flexor bilaterally. No focal deficit in strength or sensitivity was observed at any time. He became unable to walk, as gait deteriorated with a significant apraxic component. In the following days, clinical symptoms deteriorated until the patient's condition progressed to akinetic mutism.

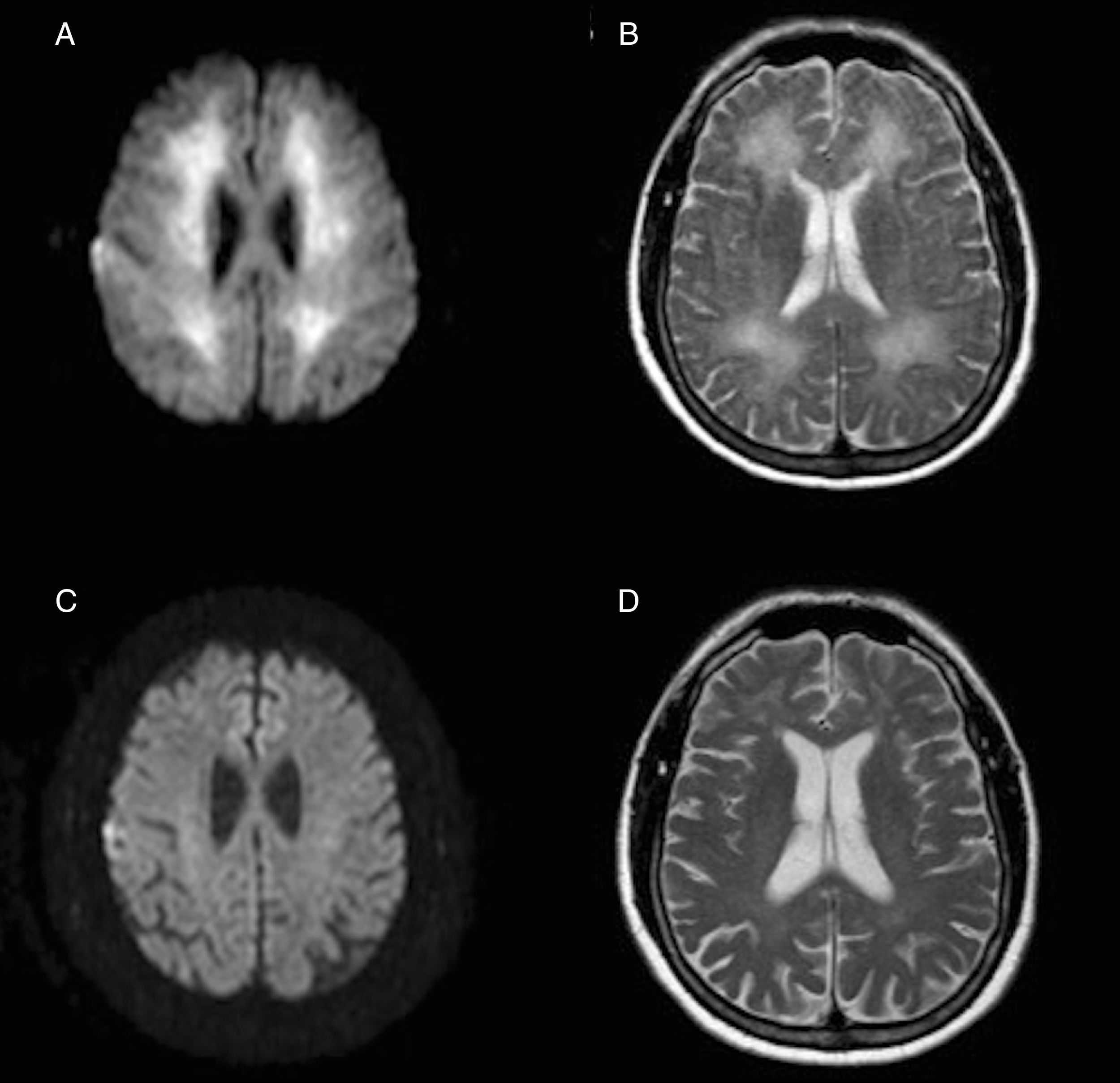

A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed 3 weeks after the hypoxic event revealed extensive involvement of the white matter in T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences, and restriction in diffusion-weighted sequences (Fig. 1A and B).

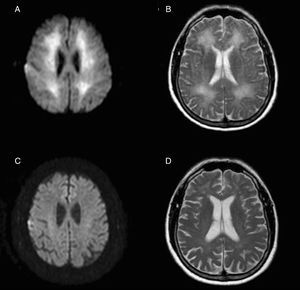

Axial MRI images obtained 3 weeks after the hypoxic event, with restricted diffusion in the diffusion-weighted sequence (A) and hyperintensity in the T2-weighted sequence (B) extensively affecting the whole periventricular white matter. Below, diffusion-weighted (C) and T2-weighted sequences (D) obtained one year later show the resolution of both alterations.

General analysis including a coagulation study, autoimmunity study, serology test, copper test, lactate tests, and arylsulphatase A test yielded no relevant findings. The patient received general care and rehabilitation therapy and his condition improved gradually; after 2 months and a half, he had recovered to a baseline state and was discharged. One year after admission, the patient remains asymptomatic and can perform the activities of daily living independently. Likewise, MRI scans show a very favourable evolution (Fig. 1C and D). Considering the clinical and radiological recovery, and having excluded other possible inflammatory or infectious causes, final diagnosis was reversible DPHL.

This condition is typically characterised by a biphasic course with an immediate recovery after an episode of cerebral hypoxia-induced coma; onset is followed by neuropsychiatric symptoms days or weeks after the episode.1

The cause most frequently associated with this entity is carbon monoxide poisoning,2 but it may also occur after other such anoxic events as strangulation,3 haemorrhagic shock,4,5 or opiate or sedative agent abuse,6,7 as in our case.

The precise pathophysiological mechanism of DPHL is still to be determined, but given the similarity between the demyelinating findings on the MRI and those typical of metachromatic leukodystrophy, it has been suggested that a deficiency of arylsulphatase A (which is necessary for myelin turnover) may predispose to this syndrome.8,9 However, several similar cases with normal levels of this enzyme have also been published.10 Other mechanisms involved are the myelin toxicity of some external agents,11 alterations in the regulation of white matter vascularisation,12 or the specific susceptibility of white matter oligodendrocytes to cerebral hypoxia.13

The characteristic clinical symptoms include cognitive/behavioural impairment, disorientation, frontal signs, amnesia, parkinsonism, akinetic mutism, and psychosis. MRI images typically show hyperintensity in T2- and diffusion-weighted sequences; cerebrospinal fluid analysis yields normal results. There is no specific treatment, and prognosis may vary; complete recovery may be achieved, probably depending on the patient's age.1

In conclusion, DPHL is an infrequent entity with characteristic clinical symptoms which should be known in order to avoid administering unnecessary treatments and diagnostic tests; cranial MRI scans are useful for diagnosis and follow-up.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Tainta M, de la Riva P, Urtasun MÁ, Martí-Massó JF. Leucoencefalopatía posthipóxica diferida reversible. Neurología. 2018;33:59–61.