The article by Carnero-Pardo published in Neurología1 has revived the debate on the possible obsolescence of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).2 In his review article, the author advocates retiring the MMSE and argues that there are other tests which are shorter and more effective for detecting cognitive impairment. We feel that Dr Carnero-Pardo's arguments are biased by the lack of time faced by clinicians in Spain as well as by other specific circumstances.

The 4 arguments the author uses to support the ‘well-deserved retirement’ of the MMSE are the lack of standardisation for its items, the effect of socio-educational variables on results, its limited effectiveness for detecting cognitive impairment, and the fact that it is copyright-protected. At present, however, these arguments lack the scientific basis necessary to be considered valid, for several reasons.

- (1)

It is quite true that some items (words to be memorised, phrases to repeat, etc.) vary between versions and that a more uniform administration process would be helpful. Nevertheless, what defines a test's construct validity (and general validity) is the extent to which each item assesses what the test claims to assess. This has been demonstrated repeatedly in the case of the MMSE.3,4 In Spain, the version translated by Tolosa et al.5 and the version validated by the NORMACODEM group6 are almost identical, and very similar to the original MMSE. These, along with the Mini-Examen Cognoscitivo (MEC, the first adaptation of the MMSE in Spain) are the most widely-used versions. The latest 30-point version of the MEC is more similar to the original MMSE, which indicates a progressive standardisation process.7

- (2)

The MMSE is sensitive to sociodemographic variables. This is also true for most cognitive tests, although in varying degrees: the clock drawing test, for example, is more affected by these variables. The effectiveness of the MMSE is known to be lower among Spanish speakers than among English speakers. Likewise, sex, age, educational level (<9 years of education), and especially illiteracy limit its effectiveness for assessing cognitive impairment and detecting dementia.3 Illiteracy, however, does not seem to affect performance when the cut-off point is lowered, as Carnero-Pardo himself shows diagnostic utility of 0.86 in a sample in which illiterate individuals constituted 14.3%.8 Another option would be to modify those items sensitive to illiteracy or a low educational level, as one study did to assess cognitive impairment in an Asian population,9 or to include functional assessment scales with good sensitivity and high specificity for dementia screening.10 Both of these strategies were used in the NEDICES study.11 Furthermore, it is commonly accepted that people with severe limitations for completing cognitive evaluations (hearing or visual impairment, illiteracy) must be thoroughly assessed using ad hoc tools.

- (3)

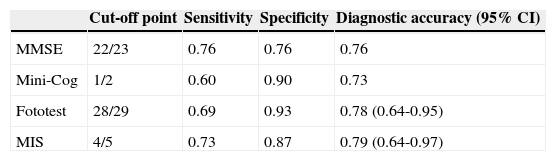

As Carnero-Pardo correctly states, cognitive impairment (whether mild cognitive impairment or dementia) is the sole target to be detected, but his view on the utility of the MMSE is erroneous. The sensitivity and specificity values that he mentions, taken from a meta-analysis,12 do not correspond to subjects with cognitive impairment but to subjects with mild cognitive impairment. The data he presents,1,13 which supposedly favour the Fototest, are biased since he did not use the optimal cut-off point for the MMSE. Comparative data from the Fototest and other short cognitive tests show similar diagnostic performance when the optimal cut-off points are applied (Table 1).

Table 1.Performance of MMSE, Mini-Cog, and Fototest for detecting cognitive impairment.

Cut-off point Sensitivity Specificity Diagnostic accuracy (95% CI) MMSE 22/23 0.76 0.76 0.76 Mini-Cog 1/2 0.60 0.90 0.73 Fototest 28/29 0.69 0.93 0.78 (0.64-0.95) MIS 4/5 0.73 0.87 0.79 (0.64-0.97) MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; MIS: Memory Impairment Screen.

Data are taken from Carnero-Pardo et al.13,14

- (4)

As far as we are concerned, the copyright of the MMSE is only applicable to the original English version of the questionnaire and to validated and registered ad hoc versions in other languages and only in such cases in which they are used for potentially lucrative economic activities (clinical trials, among others). It seems highly unlikely that researchers would have to pay copyright fees in any other than the circumstances described above especially since public healthcare is a non-profit field, and considering that we do not use the original version. To the best of our knowledge, no lawsuits have ever been brought for using the MMSE in the contexts we have mentioned (even when results are subsequently published).

As previously stated and as shown in Carnero-Pardo's well-chosen figure, the MMSE has become a standard tool for assessing cognitive function, especially in the elderly (nearly 30000 hits on PubMed in 2012). This is the case because the test now exists in so many languages and countries, and because of its versatility, which has given rise to multiple versions: short versions, long versions (3 MS), telephone versions, and versions adapted to specific populations (MMSE-37). Standard tools should not be retired; at most, they might be replaced by better tools, but there is no consensus as to which tool is better than this one. As such, there is no scientific basis for retiring the MMSE, although adaptations for specific populations or studies have already been made and are certainly welcome. While better cognitive assessment tools may be available in the future, the MMSE is the most widely accepted option to date.

FundingThis study has received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Olazarán Rodríguez J, Bermejo Pareja F. No hay razones científicas para jubilar al MMSE. Neurología. 2015;30:589–591.