Behavioural and psychiatric symptoms (BPS) are frequent in neurological patients, contribute to disability, and decrease quality of life. We recorded BPS prevalence and type, as well as any associations with specific diagnoses, brain regions, and treatments, in consecutive outpatients examined in a cognitive neurology clinic.

MethodA retrospective analysis of 843 consecutive patients was performed, including a review of BPS, diagnosis, sensory impairment, lesion topography (neuroimaging), and treatment. The total sample was considered, and the cognitive impairment (CI) group (n=607) was compared to the non-CI group.

ResultsBPS was present in 59.9% of the patients (61.3% in the CI group, 56.4% in the non-CI group). One BPS was present in 31.1%, two in 17.4%, and three or more in 11.4%. BPS, especially depression and anxiety, are more frequent in women than in men. Psychotic and behavioural symptoms predominate in subjects aged 65 and older, and anxiety in those younger than 65. Psychotic symptoms appear more often in patients with sensory impairment. Psychotic and behavioural symptoms are more prevalent in patients with degenerative dementia; depression and anxiety in those who suffer a psychiatric disease or adverse effects of substances; emotional lability in individuals with a metabolic or hormonal disorder; hypochondria in those with a pain syndrome; and irritability in subjects with chronic hypoxia. Behavioural symptoms are more frequent in patients with anomalies in the frontal or right temporal or parietal lobes, and antipsychotics constitute the first line of treatment. Leaving standard treatments aside, associations were observed between dysthymia and opioid analgesics, betahistine and statins, and between psychotic symptoms and levodopa, piracetam, and vasodilators.

Los síntomas conductuales y psiquiátricos (SCP) son frecuentes en el enfermo neurológico, contribuyen a producir discapacidad y reducen la calidad de vida. Se ha observado, en pacientes de neurología cognitiva, la prevalencia y tipo de SCP y su asociación con diagnósticos, regiones cerebrales o tratamientos específicos.

MétodoAnálisis retrospectivo de 843 pacientes consecutivos de neurología cognitiva, revisando SCP, diagnóstico, alteración sensorial, topografía lesional en neuroimagen y tratamiento. Se contempló el total y se comparó el grupo de pacientes con deterioro cognitivo objetivo (n=607) y sin deterioro.

ResultadosHubo SCP en el 59,9% de los pacientes (61,3% en los deteriorados y 56,4% en el resto). Un 31,1% tenía un SCP, 17,4% dos y 11,4% más de dos. Los SCP son más frecuentes en mujeres, sobre todo depresión y ansiedad. En los mayores de 64 años predominan los síntomas psicóticos y conductuales, y en los menores de 65 la ansiedad. Las personas con alteración sensorial tienen más síntomas psicóticos. Se aprecian más síntomas conductuales y psicóticos en personas con demencia degenerativa, depresión y ansiedad en las que tienen enfermedad psiquiátrica o efecto nocivo de sustancias, labilidad emocional en relación con trastorno metabólico u hormonal, hipocondría en los síndromes dolorosos e irritabilidad en la hipoxia crónica. Hay más alteraciones de la conducta en pacientes con anomalía en lóbulos frontales o temporal o parietal derechos, y se tratan preferentemente con antipsicóticos. Aparte de los tratamientos estándar, se observó asociación de distimia con opioides, betahistina y estatinas, y síntomas psicóticos con levodopa, piracetam y vasodilatadores.

Cognitive neurology clinics evaluate and treat declining intellectual function. Furthermore, this decline is often associated with behaviour disorders and other typical symptoms of psychiatric diseases. These associated symptoms may indicate a psychological reaction to the self-perceived cognitive disorder, which may also be accompanied by other neurological and/or systemic manifestations. This perception can lead to different degrees of worry or alarm, depending on the patient's personality and intensity of symptoms; alarm may manifest in the form of behavioural changes and such psychiatric symptoms as depression and anxiety. In other cases, behavioural and psychiatric symptoms (BPS) are part of the array of changes arising from the dysfunction of neuronal circuits that also elicit the cognitive dysfunction. At times, both the primary and the reactive mechanisms contribute to these symptoms in varying degrees.

This is a transcendent matter because the prevalence of BPS is high in patients with neurological disease1–4 and because these clinical manifestations increase disability,5 lessen quality of life,6,7 and are very stressful for those living with the patient.6,8

The purpose of this study is to observe BPS frequency in a sample of patients seen at a cognitive neurology clinic. We also examine the association between these symptoms and specific diagnoses, or with structural changes in precise regions of the brain.

Patients and methodsWe performed a transversal retrospective analysis of a register of 857 patients examined in a cognitive neurology clinic. Records lacking any of the essential data for this study were excluded. Patients were categorised in 2 groups. Those in group 1 had a syndromic diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or dementia. In group 2, which served as a control, cognitive function was not considered pathological.

We recorded age, sex, aetiological diagnosis, and the presence and type of BPS. If BPS were detected, we examined neuroimaging studies when available. To assess their potential influence on outcomes, we checked for presence or absence of sensory alterations (visual or auditory) and recorded the type of treatment for each patient.

In a later stage, we estimated prevalence of BPS and examined the association between these symptoms and different aetiological diagnoses (disease types). We examined the possibility of a link between BPS and neuroimaging anomalies in specific regions (disease topography). We also compared results from groups 1 and 2.

BPS occurring during sleep, such as somnambulism or REM sleep behaviour disorders, were not included. BPS recognised in this study were limited to those relevant to the diagnosis, affecting family life, or requiring treatment or modifying treatment. We did not examine sporadic or mild symptoms with no significance and no repercussions on treatment decisions.

Sensory disorders were limited to changes interfering with functional capacity in patients who refused corrective lenses or hearing aids, or whose functions could not be corrected with these devices.

We recorded any visible changes in MR or CT images that were considered symptomatic. Where such changes were present, we recorded the affected hemisphere and lobe; the deep subcortical area was considered separately. Type of alteration (atrophy, infarct, tumour, etc.) was not recorded.

When recording treatments, we excluded eye drops and other occasional medications.

Generic diagnoses and treatments were listed to ensure proper sample sizes for the analysis; specific diagnoses and treatments were recorded to detect any associations between them and presence of BPS.

SPSS 15.0 software was used for the statistical analysis. Associations between qualitative variables were checked using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test; the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative variables between groups 1 and 2. Two significance levels were used: P<.05 and P<.01.

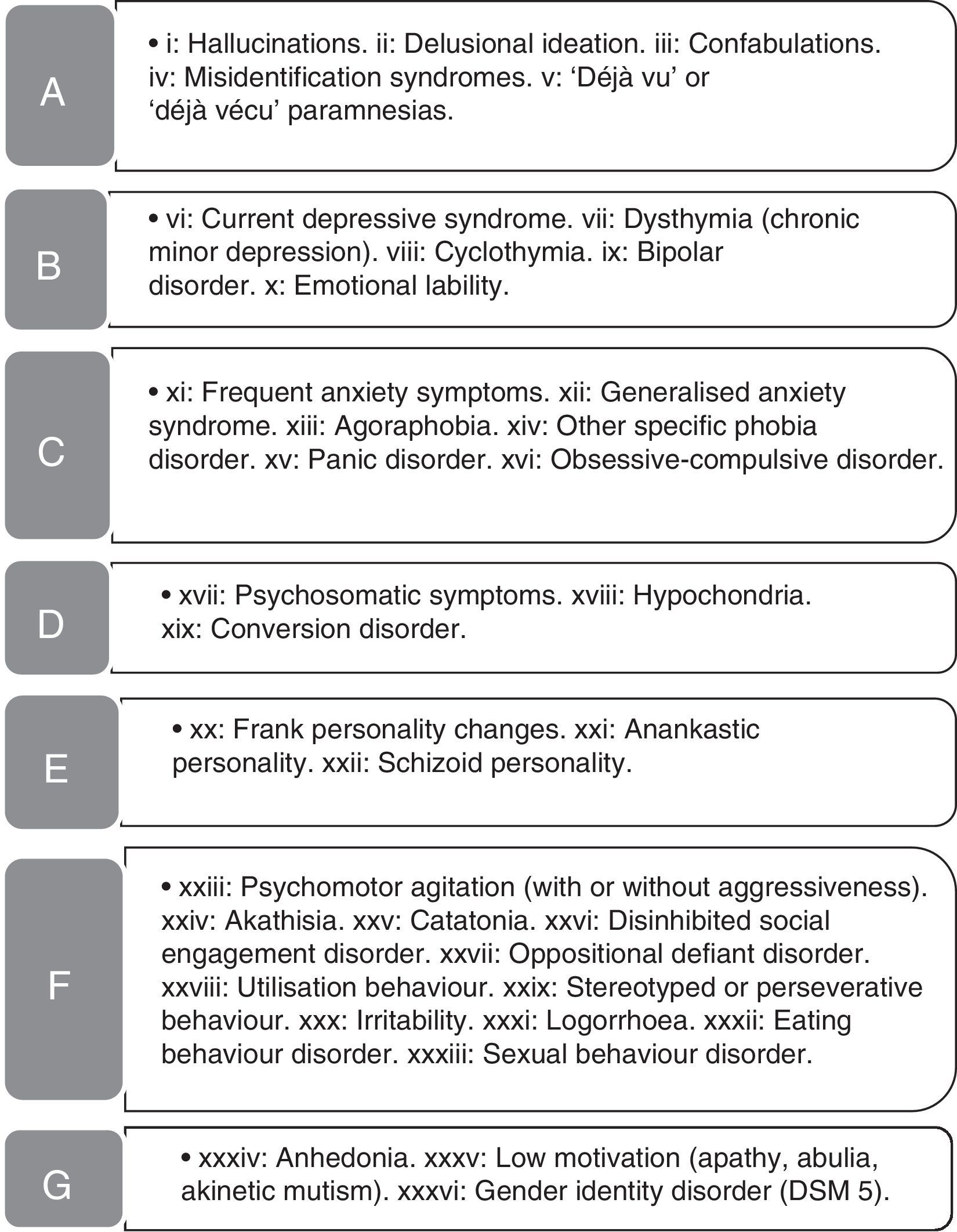

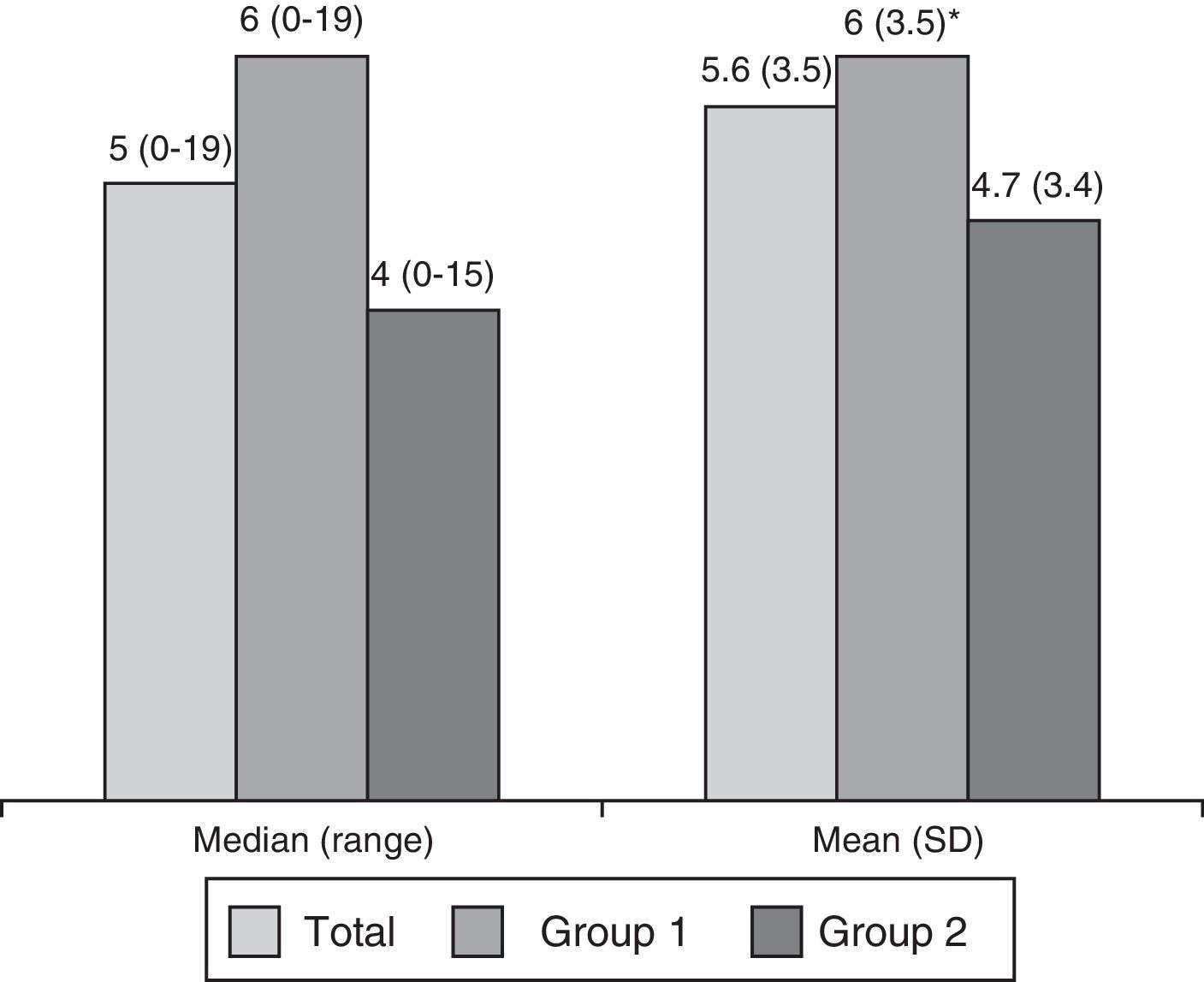

ResultsWe analysed 843 subjects, 607 in group 1 and 236 in group 2. At least one BPS was present in 59.9% (61.3% in group 1 and 56.4% in group 2). Subjects could be divided further into those with one BPS (31.1% of the total, or 31.1% of group 1 and 30.9% of group 2); 2 BPS (17.4%, 18.0%, and 16.1% respectively); or more than 2 BPS (11.4%, 12.2%, and 9.3%). Table 1 displays prevalence of BPS (Fig. 1).

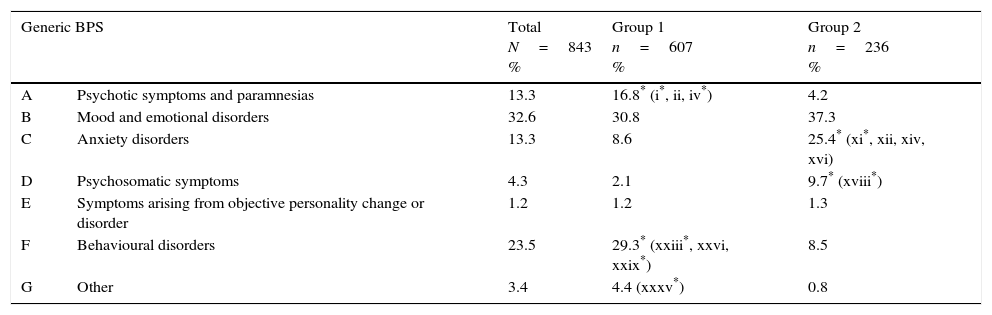

Behavioural and psychiatric symptoms (BPS) in patient sample.

| Generic BPS | Total N=843 % | Group 1 n=607 % | Group 2 n=236 % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Psychotic symptoms and paramnesias | 13.3 | 16.8* (i*, ii, iv*) | 4.2 |

| B | Mood and emotional disorders | 32.6 | 30.8 | 37.3 |

| C | Anxiety disorders | 13.3 | 8.6 | 25.4* (xi*, xii, xiv, xvi) |

| D | Psychosomatic symptoms | 4.3 | 2.1 | 9.7* (xviii*) |

| E | Symptoms arising from objective personality change or disorder | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| F | Behavioural disorders | 23.5 | 29.3* (xxiii*, xxvi, xxix*) | 8.5 |

| G | Other | 3.4 | 4.4 (xxxv*) | 0.8 |

In parentheses: specific symptoms (see Fig. 1) that are significantly more frequent than in the other group (P<.05).

Group 1: patients with dementia or mild cognitive impairment; Group 2: patients with no objective cognitive impairment (controls).

Behavioural and psychiatric symptoms (BPS) examined in the study. List of BPS detected in our patient sample. The names of the symptom groups (A-G) are given in Table 1.

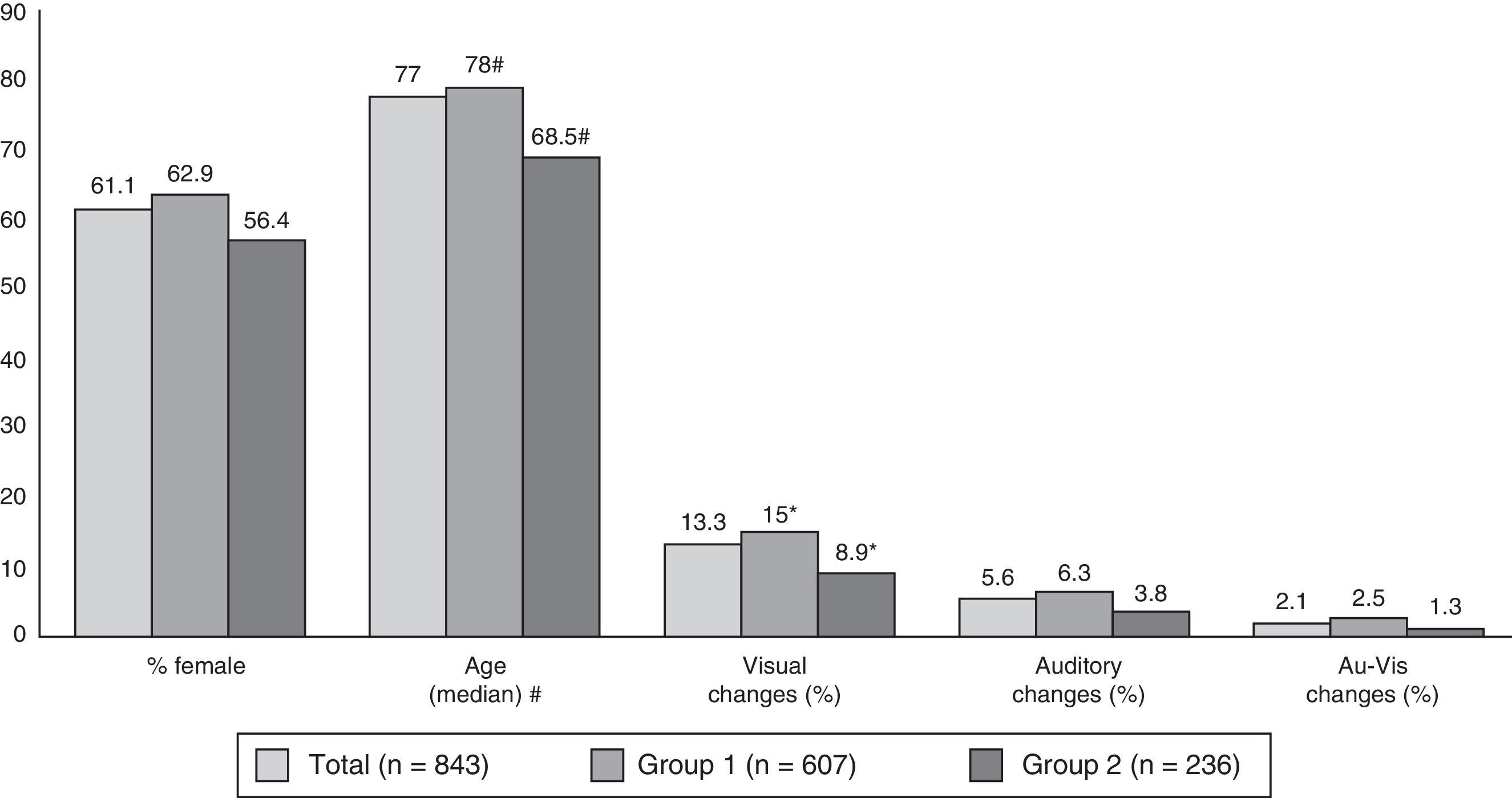

Fig. 2 shows the breakdown of the sample by age, sex, and presence or absence of sensory changes. Subjects aged 65 and older accounted for 80.5% of the total (89.3% of group 1 and 58% of group 2); the difference was significant (P<.01). Patients in group 1 were older overall and had a higher prevalence of visual changes than those in group 2.

Breakdown of patients by sex, age, and sensory changes. Au-Vis: auditory and visual. #: mean±SD (range): Total, 72.9±14.4 (14-104); Group 1, 76.6±10.5 (19-104); Group 2, 63±18.3 (19-95). Intergroup differences are statistically significant for P<.01 (*: intergroup differences statistically significant for P<.05).

In the full sample and in both subgroups, BPS was more frequently observed in women (65.2%, 64.7%, and 66.9% in women, vs 51.5%, 55.6%, and 42.7% in men; P<.01, P<.05, P<.01). Differences were marked for depression and anxiety. In men, more cases of BPS was detected overall in cases than in controls (55.6% vs 42.7%), whereas there were no significant differences between cases and controls in women.

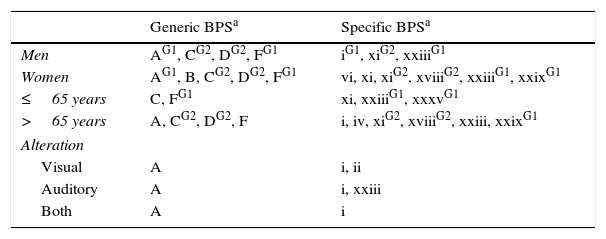

Presence of BPS was similar in subjects older than and younger than 65, although there was a higher rate of psychotic symptoms and behaviour disorders in older subjects, and of anxiety disorders in younger subjects (Table 2). Specific BPS in the older subjects included hallucinations, dysidentity syndromes, and agitation; symptoms of anxiety were predominant in the younger group.

Most prevalent behavioural and psychiatric symptoms (P<.01) broken down by sex, age, and presence of sensory changes.

| Generic BPSa | Specific BPSa | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | AG1, CG2, DG2, FG1 | iG1, xiG2, xxiiiG1 |

| Women | AG1, B, CG2, DG2, FG1 | vi, xi, xiG2, xviiiG2, xxiiiG1, xxixG1 |

| ≤65 years | C, FG1 | xi, xxiiiG1, xxxvG1 |

| >65 years | A, CG2, DG2, F | i, iv, xiG2, xviiiG2, xxiii, xxixG1 |

| Alteration | ||

| Visual | A | i, ii |

| Auditory | A | i, xxiii |

| Both | A | i |

When prevalence is higher in only one group, that group is indicated in superscript.

G1: Group 1; G2: Group 2.

Prevalence of BPS did not vary according to presence or absence of sensory changes, although we found psychotic symptoms to be more frequent in people with visual and/or auditory changes (Table 2).

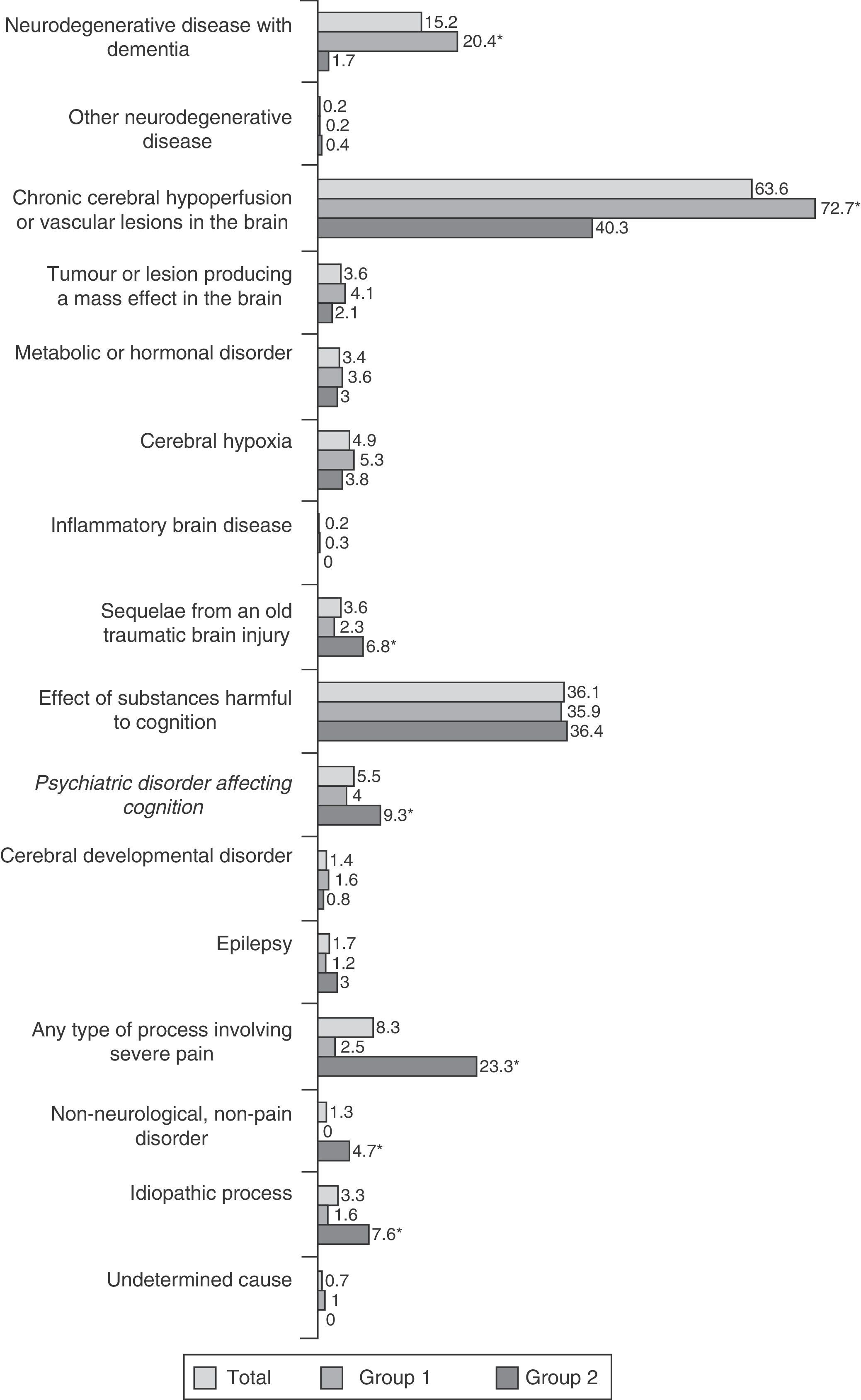

We registered 84 aetiological diagnoses, distributed among 18 categories (Fig. 3). Degenerative and cerebrovascular diseases were predominant in group 1; in contrast, the frequency of pain disorders, sequelae of traumatic brain injury, and psychiatric illnesses, as well as the absence of objective neurological disease, was higher in group 2. Regarding specific diagnoses, we observed higher rates of Alzheimer disease, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and cerebrovascular disease in group 1. Group 2 also demonstrated a higher prevalence of dysthyroidism, sequelae of traumatic brain injury, somatic manifestations of anxiety, psychogenic or psychosomatic symptoms, familial essential tremor, muscle tension headaches, migraine, cervical brachiocephalic syndrome of cervical origin, polyneuropathy with pain or paraesthesia, and cases in which no neurological or pain disorders were present.

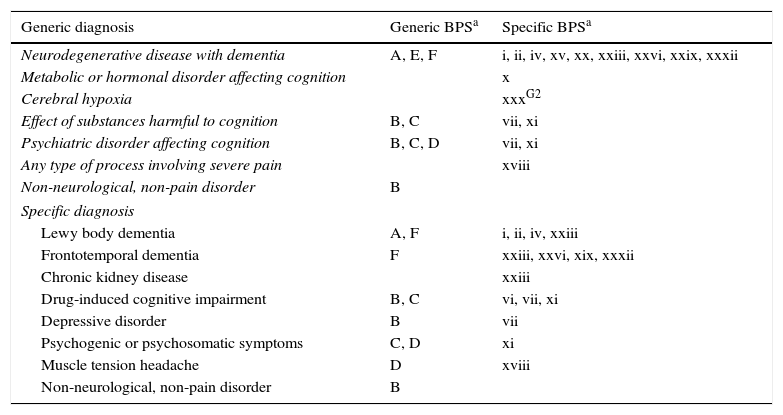

Table 3 lists noteworthy types of BPS by diagnosis. Degenerative diseases were more likely to be associated with psychotic symptoms, personality changes, and behavioural disorders; patients exhibiting substance abuse showed a higher prevalence of anxiety and mood disorders; psychiatric diagnoses were associated with mood disorders, anxiety, and psychosomatic symptoms. Lastly, patients with no neurological or pain disorders displayed higher rates of affective disorders. Emotional lability was more common in individuals with metabolic or hormonal disorders; irritability in controls with cerebral hypoxia; and hypochondria symptoms in individuals experiencing pain of any type.

Breakdown of the most common BPS (P<.01) by diagnosis.

| Generic diagnosis | Generic BPSa | Specific BPSa |

|---|---|---|

| Neurodegenerative disease with dementia | A, E, F | i, ii, iv, xv, xx, xxiii, xxvi, xxix, xxxii |

| Metabolic or hormonal disorder affecting cognition | x | |

| Cerebral hypoxia | xxxG2 | |

| Effect of substances harmful to cognition | B, C | vii, xi |

| Psychiatric disorder affecting cognition | B, C, D | vii, xi |

| Any type of process involving severe pain | xviii | |

| Non-neurological, non-pain disorder | B | |

| Specific diagnosis | ||

| Lewy body dementia | A, F | i, ii, iv, xxiii |

| Frontotemporal dementia | F | xxiii, xxvi, xix, xxxii |

| Chronic kidney disease | xxiii | |

| Drug-induced cognitive impairment | B, C | vi, vii, xi |

| Depressive disorder | B | vii |

| Psychogenic or psychosomatic symptoms | C, D | xi |

| Muscle tension headache | D | xviii |

| Non-neurological, non-pain disorder | B | |

When prevalence is higher in only one group, that group is indicated in superscript.

G1: Group 1; G2: Group 2.

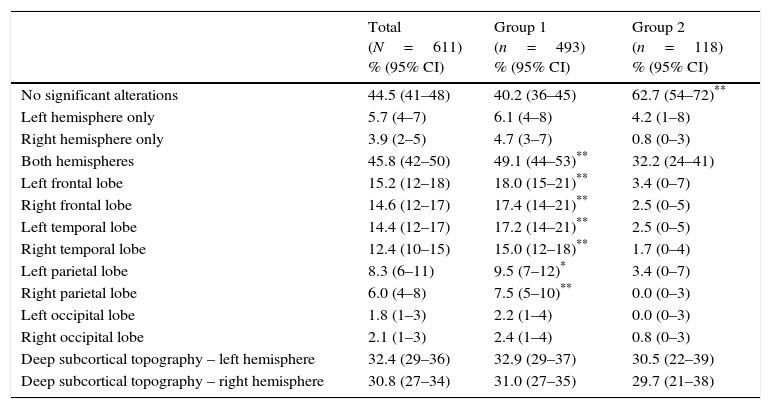

Table 4 shows the topography of changes observed in the neuroimaging studies of patients with BPS. Bihemispheric changes were more common in cases than in controls, and cases were particularly more likely to show changes in the frontal, temporal, or parietal lobes. Imaging studies from controls were less likely to show significant changes. Anomalies were more frequent in deep subcortical regions than in superficial regions, but intergroup differences were not significant.

Topography of the changes observed in neuroimaging studies for cases with BPS examined using brain CT or MRI.

| Total (N=611) % (95% CI) | Group 1 (n=493) % (95% CI) | Group 2 (n=118) % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No significant alterations | 44.5 (41–48) | 40.2 (36–45) | 62.7 (54–72)** |

| Left hemisphere only | 5.7 (4–7) | 6.1 (4–8) | 4.2 (1–8) |

| Right hemisphere only | 3.9 (2–5) | 4.7 (3–7) | 0.8 (0–3) |

| Both hemispheres | 45.8 (42–50) | 49.1 (44–53)** | 32.2 (24–41) |

| Left frontal lobe | 15.2 (12–18) | 18.0 (15–21)** | 3.4 (0–7) |

| Right frontal lobe | 14.6 (12–17) | 17.4 (14–21)** | 2.5 (0–5) |

| Left temporal lobe | 14.4 (12–17) | 17.2 (14–21)** | 2.5 (0–5) |

| Right temporal lobe | 12.4 (10–15) | 15.0 (12–18)** | 1.7 (0–4) |

| Left parietal lobe | 8.3 (6–11) | 9.5 (7–12)* | 3.4 (0–7) |

| Right parietal lobe | 6.0 (4–8) | 7.5 (5–10)** | 0.0 (0–3) |

| Left occipital lobe | 1.8 (1–3) | 2.2 (1–4) | 0.0 (0–3) |

| Right occipital lobe | 2.1 (1–3) | 2.4 (1–4) | 0.8 (0–3) |

| Deep subcortical topography – left hemisphere | 32.4 (29–36) | 32.9 (29–37) | 30.5 (22–39) |

| Deep subcortical topography – right hemisphere | 30.8 (27–34) | 31.0 (27–35) | 29.7 (21–38) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval. Percentage is significantly higher than in the other group.

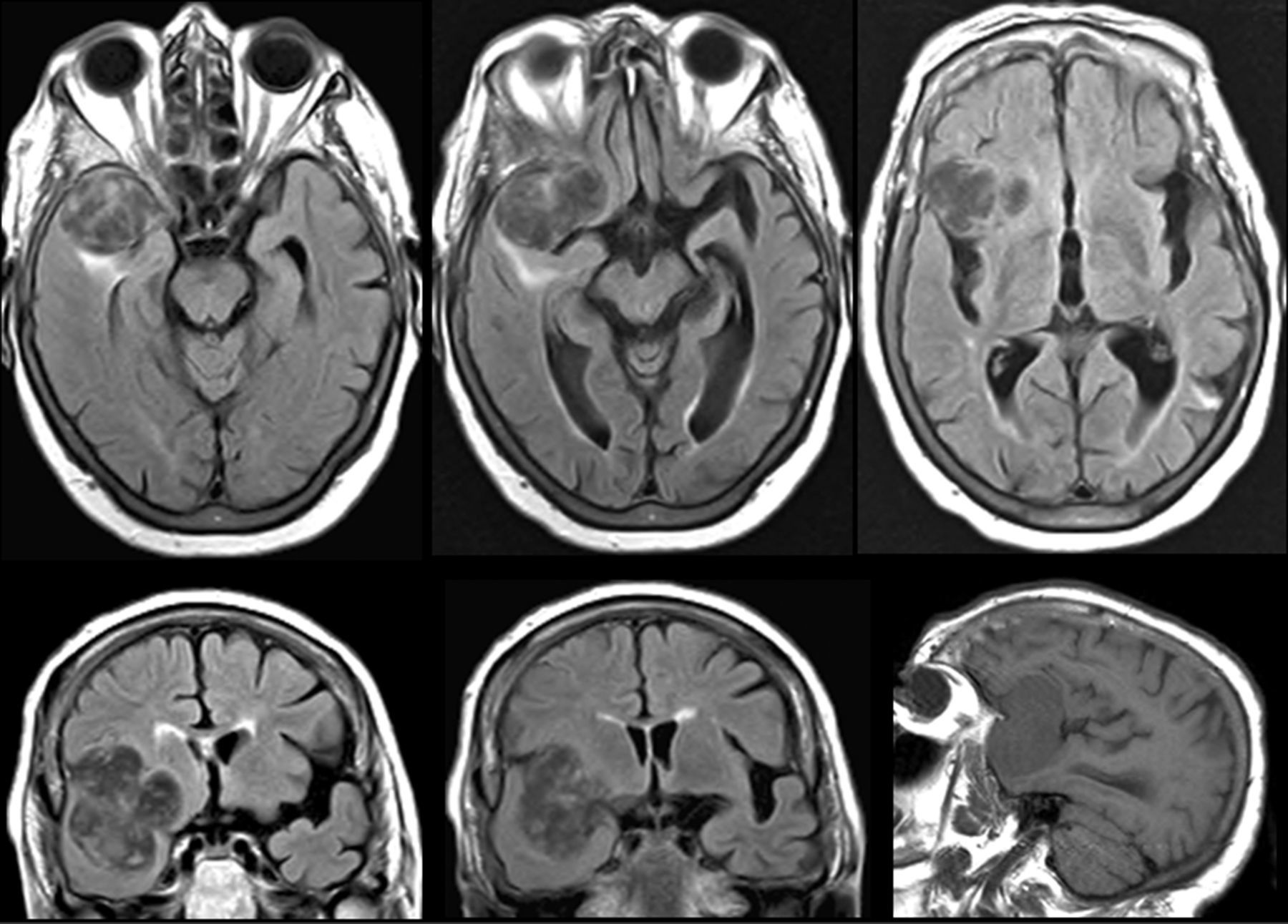

Bihemispheric presence of anomalies was associated with behaviour alterations (P<.01) and psychotic symptoms (P<.05), whereas patients with no changes in neuroimaging studies showed a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders (P<.01) and of mood disorders (P<.05). Changes in the frontal lobes and in the right temporal or parietal lobe (P<.01) or the left parietal lobe (P<.05) were associated with more behaviour disorders; changes in the right frontal lobe were linked to psychotic symptoms (P<.05). Examining the most frequent specific BPS (P<.01), we found an association between misidentification syndromes and right temporal lesions (Fig. 4); between agitation and left frontal, right frontal, and right temporal anomalies; social disinhibition and isolated right hemisphere or right frontal and left temporal anomalies; stereotyped behaviours and left frontal, right frontal, and right parietal anomalies; and eating behaviour disorders with right frontal, left frontal, and right temporal anomalies.

Cerebral MRI of an 81-year-old woman. One-year history of delusional ideation; in recent months, she had also exhibited reduplicative paramnesia and altered social and eating behaviours. A space-occupying lesion was detected in the anterior frontal posteroinferior region of the right temporal lobe.

Reported medications included 172 substances, classified in 43 groups. Fig. 5 indicates that patients in group 1 took more drugs than those in group 2.

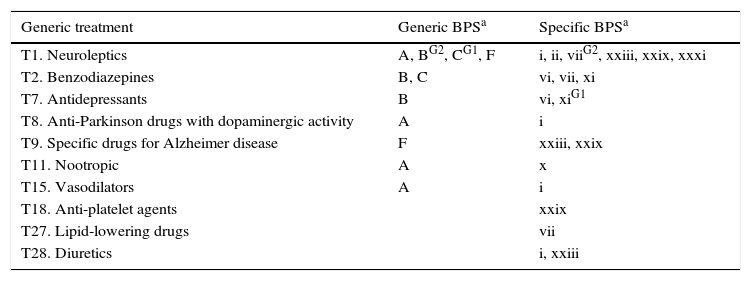

Lastly, Tables 5 and 6 list associations between BPS and drug treatments. Given the high percentage of polymedicated patients and the influence of other factors (such as the diagnosis), drug associations were only evaluated if more than 1% of the cases showed the association with a significance level of P<.01.

Breakdown of the most common BPS (P<.01) by drug therapeutic group.

| Generic treatment | Generic BPSa | Specific BPSa |

|---|---|---|

| T1. Neuroleptics | A, BG2, CG1, F | i, ii, viiG2, xxiii, xxix, xxxi |

| T2. Benzodiazepines | B, C | vi, vii, xi |

| T7. Antidepressants | B | vi, xiG1 |

| T8. Anti-Parkinson drugs with dopaminergic activity | A | i |

| T9. Specific drugs for Alzheimer disease | F | xxiii, xxix |

| T11. Nootropic | A | x |

| T15. Vasodilators | A | i |

| T18. Anti-platelet agents | xxix | |

| T27. Lipid-lowering drugs | vii | |

| T28. Diuretics | i, xxiii |

When prevalence is higher in only one group, that group is indicated in superscript.

G1: Group 1; G2: Group 2.

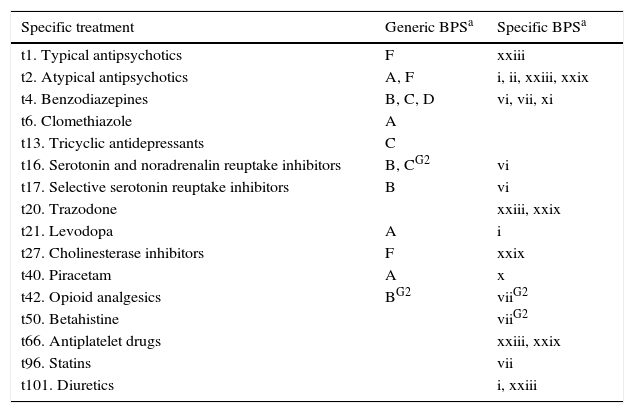

Breakdown of BPS associated with specific treatments (P<.01).

| Specific treatment | Generic BPSa | Specific BPSa |

|---|---|---|

| t1. Typical antipsychotics | F | xxiii |

| t2. Atypical antipsychotics | A, F | i, ii, xxiii, xxix |

| t4. Benzodiazepines | B, C, D | vi, vii, xi |

| t6. Clomethiazole | A | |

| t13. Tricyclic antidepressants | C | |

| t16. Serotonin and noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors | B, CG2 | vi |

| t17. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | B | vi |

| t20. Trazodone | xxiii, xxix | |

| t21. Levodopa | A | i |

| t27. Cholinesterase inhibitors | F | xxix |

| t40. Piracetam | A | x |

| t42. Opioid analgesics | BG2 | viiG2 |

| t50. Betahistine | viiG2 | |

| t66. Antiplatelet drugs | xxiii, xxix | |

| t96. Statins | vii | |

| t101. Diuretics | i, xxiii |

When prevalence is higher in only one group, that group is indicated in superscript.

G1: Group 1; G2: Group 2.

This study aimed to calculate BPS prevalence in patients examined in a cognitive neurology clinic. It also examined associations between BPS and different factors in patients’ medical records, and compared findings between patients with and without objective cognitive impairment. The study did not enter into the genotypes that may affect susceptibility to developing BPS.9,10

It detected a high rate of BPS (59.9%) similar to those yielded by other studies reporting rates of over 50% in patients seen in outpatient neurology clinics.1,4 We also detected more BPS in patients with cognitive impairment (61.3%) than in patients in group 2 (56.4%), a difference that has already been reported.6,8,11

Frequencies of affective and anxiety symptoms, and of personality changes and psychosomatic symptoms (32.6%, 13.3%, 1.2%, and 4.3%, respectively), are similar to those reported by Jefferies et al.2 in hospitalised neurological patients (24.8%, 12.7%, 2%, and 4.5%). The differences are due to the dissimilar percentages of patients with cognitive impairment (72% in this study vs 17.7% in Jefferies et al.2). Psychotic symptoms were more frequent in group 1 (16.8%) than in group 2 (4.2%), as were behavioural changes (29.3% vs 8.5%). In contrast, we observed a higher prevalence of anxiety and psychosomatic symptoms in group 2 (25.4% and 9.7% vs 8.6% and 2.1%). It is understood that dementia disorders are more likely than other neurological disorders to entail dysfunction of cerebral areas related to behavioural control and perception. This gives rise to behavioural and psychotic symptoms as a primary manifestation. On the other hand, the anosognosia displayed by these patients may actually reduce those symptoms of mental illness that require a greater degree of introspection and better cognitive functioning in order to manifest.

A higher percentage of women than men display cognitive impairment; this is also the case of BPS, as has been reported by other studies.12 The overall female predominance is accounted for by higher rates of depression and anxiety; these findings are supported by the literature.13,14

Psychotic and behavioural symptoms are predominant in subjects aged 65 and older; younger subjects are more likely to have anxiety. Older subjects in group 1 display more agitation and stereotyped behaviour, whereas younger subjects exhibit more behavioural changes, apathy, and agitation (Table 2). These differences seem entirely logical. The older patients include those who have had psychotic symptoms from a younger age, as well as older patients who have developed symptoms of dementia or confusional syndrome.15 Anxiety, on the other hand, often develops in young adults. When it is present in older patients, it often has a long-standing chronic profile or corresponds to an exacerbation due to incidental problems.16

Sensory changes are associated with a higher incidence of psychotic symptoms. One study found a higher prevalence of visual disturbances in individuals with psychotic symptoms and schizophrenia.17 Another study in patients with dementia found auditory and visual disorders to be associated with the appearance of psychotic symptoms.18

Psychotic symptoms were more prevalent in group 1 than in group 2; this could be explained by the older age overall in patients with dementia, and the higher prevalence of sensory alterations that could contribute to these symptoms. Furthermore, dementia syndromes include psychotic symptoms; some are specific, such as the typical visual hallucinations in Lewy body dementia, while others are more varied, such as those in established Alzheimer disease and in vascular dementia.19–21

We can expect a higher incidence of anxiety and mood disorders among patients with psychiatric conditions, or those whose symptoms were solely derived from substance abuse. Likewise, hypochondria can be expected among individuals with pain disorders. Furthermore, irritability is a documented symptom of patients with chronic hypoxia, as seen in this study.22 The higher rates of emotional lability observed in individuals with metabolic or hormonal disorders (17.2% vs 3.1% in the rest of the population) are not as easily justified. We know that this symptom commonly appears in different types of dementia,23 and that corticotropin-releasing hormone and cerebral glucocorticoid receptors intervene in regulating emotional expression.24 Therefore, it is understandable that emotional lability would be present in cognitive disorders arising from the hormonal or metabolic disorders that affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

The topographical analysis shows that patients with cognitive impairment are more likely to display affectation of the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes than of the occipital lobes. This is to be expected based on the typical impact pattern in degenerative dementias, and considering that strokes arise more frequently from the medial or anterior cerebral arteries than from the posterior cerebral artery. In the BPS correlation study, we observed that frontal lobe alterations, and right-hemisphere temporal or parietal lesions, were associated with higher numbers of behaviour disorders. Agitation was associated with alterations in the frontal lobes and right temporal lobe; disinhibition with the right frontal lobe; stereotyped behaviour with the frontal lobes and right parietal lobe; and eating behaviour disorders with the frontal lobes and right temporal lobe. These findings are supported by current research.25–33 The association between misidentification syndromes and the right temporal lobe is also compatible with earlier observations.34,35

Associations were also detected between certain BPS and drugs. We presume that most drugs were prescribed to treat BPS, but our methodology does not allow us to detect the cases in which BPS appeared as the side effects of treatment.

Given that polymedication promotes confusional syndrome,36,37 the higher frequency of BPS in group 1 than in group 2 may be linked to their higher consumption of medications (Fig. 5).

It is logical to find consumption of neuroleptics in patients with psychotic symptoms, benzodiazepine consumption in those with anxiety, and antidepressants for those with affective disorders. Use of antipsychotics was also higher among patients with non-psychotic behaviour disorders, including agitation, stereotyped behaviours, and logorrhoea. Antipsychotic agents are also often used to combat BPS arising in dementia, even though risks are present and the level of evidence of efficacy is lower.38,39 However, only a handful of published studies have examined the effectiveness of these drugs on different non-psychotic behaviour disorders, or whether they might elicit certain disorders.

It should be noted that 18 of the patients with stereotypies were taking mirtazapine or trazodone. These patients had frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, or cerebrovascular disease; these disorders frequently feature frontal dysfunction, which may be accompanied by stereotyped behaviours.40,41 It is therefore more likely that the symptom would be due to the disease than to treatment.

Psychotic symptoms are not uncommon in patients taking dopaminergic anti-Parkinson drugs; in fact, these drugs facilitate the appearance of such symptoms.42,43 Hallucinations are the most common symptom in dementia patients who take levodopa. This finding is consistent with the known high rate of hallucinations in patients with cortical Lewy bodies and dementia associated with Parkinson disease, or with Lewy body dementia.44–47

Some diseases are treated with anticholinesterase drugs, which also reduce BPS.48,49 Therefore, the association we found suggests that BPS are not an adverse effect of these drugs.

Piracetam was prescribed to 18.8% of the patients with psychotic symptoms and to 30% of those with emotional lability. The first group was diagnosed with neoplasm or degenerative, vascular, or metabolic disease; the second had progressive supranuclear palsy or vascular cognitive impairment. Since the underlying diseases were capable of eliciting these BPS and patients were treated with a mean of 6.85 drugs, piracetam was not believed to be responsible for the BPS listed here.

Treatment with opioid analgesics varies and the same drug may be employed at different doses. For this reason, and considering how different opioid receptors affect mood,50 patients treated with opioids may experience changes in mood ranging from euphoria to depression. Dysthymia was the most prevalent mood disorder in our sample.

Our study points to a link between vasodilators and hallucinations. Although these findings are infrequent, the literature has indicated associations between hallucinations and pentoxifylline,51–53 trimetazidine,54 flunarizine,55 and nitrovasodilators.51,56 The high frequency of BPS in cerebrovascular disease57–59 may explain the associations that have been found between betahistine and anti-platelet drugs.

The association between statins and depression supports theories indicating that lower cholesterol levels in cerebral cell membranes, or the resulting weakened response of the serotonergic system, may promote depression.60–62 Nevertheless, some authors have found the opposite to be true.63–66

The agitation and hallucinations recorded in patients taking diuretics may be attributed to temporary electrolyte imbalances, especially if the patients were predisposed to these symptoms due to advanced age or cognitive impairment.67

To summarise, BPS are frequent in neurological patients (affecting 59.9% of the sample); they are even more frequent in patients with impaired cognitive function (61.3%). Depressed mood is more common in women, patients diagnosed with a primary psychiatric disorder, users of intoxicating substances, and patients taking opioid analgesics, betahistine, or statin drugs. In our sample, anxiety was more prevalent among women, patients younger than 65, and those diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder or substance abuse. Psychotic symptoms were more frequent in patients aged 65 and older, those with visual or auditory changes or a neurodegenerative disease, and those taking levodopa, piracetam, or vasodilators. Behaviour disorders were predominant in the older group, in patients with degenerative disease, and those with structural changes in the frontal lobes or the right temporal or parietal lobes. Psychosomatic symptoms were associated with psychiatric disorders, hypochondria with pain disorders, emotional lability with metabolic or hormonal disorders plus treatment with piracetam, and irritability with chronic hypoxia.

FundingNo funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Robles Bayón A, Gude Sampedro F. Síntomas conductuales y psiquiátricos en neurología cognitiva. Neurología. 2017;32:81–91.