Autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxias (ARCA) constitute a highly heterogeneous group of neurodegenerative disorders that may present as pure or complex cerebellar syndrome and may be associated with other neurological or systemic manifestations that may help inform the complex diagnostic process.1,2 In recent years, genetic studies have become increasingly important in establishing the aetiology of certain ARCAs.3

We present the cases of 2 brothers aged 27 and 20 years old who presented psychomotor retardation and language impairment. Both were born to consanguineous parents. The patients had no family history of neurological diseases. In both cases, pregnancy, delivery, puerperium, and the neonatal period and early childhood were uneventful. Screening tests for endocrine, metabolic, and hearing disorders yielded normal results. The elder brother (patient 1) presented normal psychomotor development until the age of 7 years, when he began to display learning difficulties and motor delay (IQ: 57), with language impairment starting at the age of 17 years. The younger brother (patient 2) presented marked psychomotor retardation from the age of 5 years, with language impairment and fine motor disability (IQ: 47). At present, both patients are able to walk independently. The neurological examination of patient 1 revealed convergent strabismus of the right eye (due to right sixth cranial nerve palsy) and bilateral asymmetric cerebellar syndrome (scanning speech and appendicular dysmetria, with ataxic gait and inability to walk in tandem), as well as signs of early pyramidal tract involvement (exaggerated deep tendon reflexes and absent plantar reflex bilaterally). Patient 2 presented less marked cerebellar syndrome (scanning speech; nystagmus in left gaze), but displayed difficulty performing manipulation tasks and was unable to walk in tandem, with no pyramidal signs. The ophthalmological examination detected no alterations in either patient. Sex-, age-, weight-, and height-adjusted head circumference was normal in both patients (56.2 cm in patient 1 and 56.8 cm in patient 2).

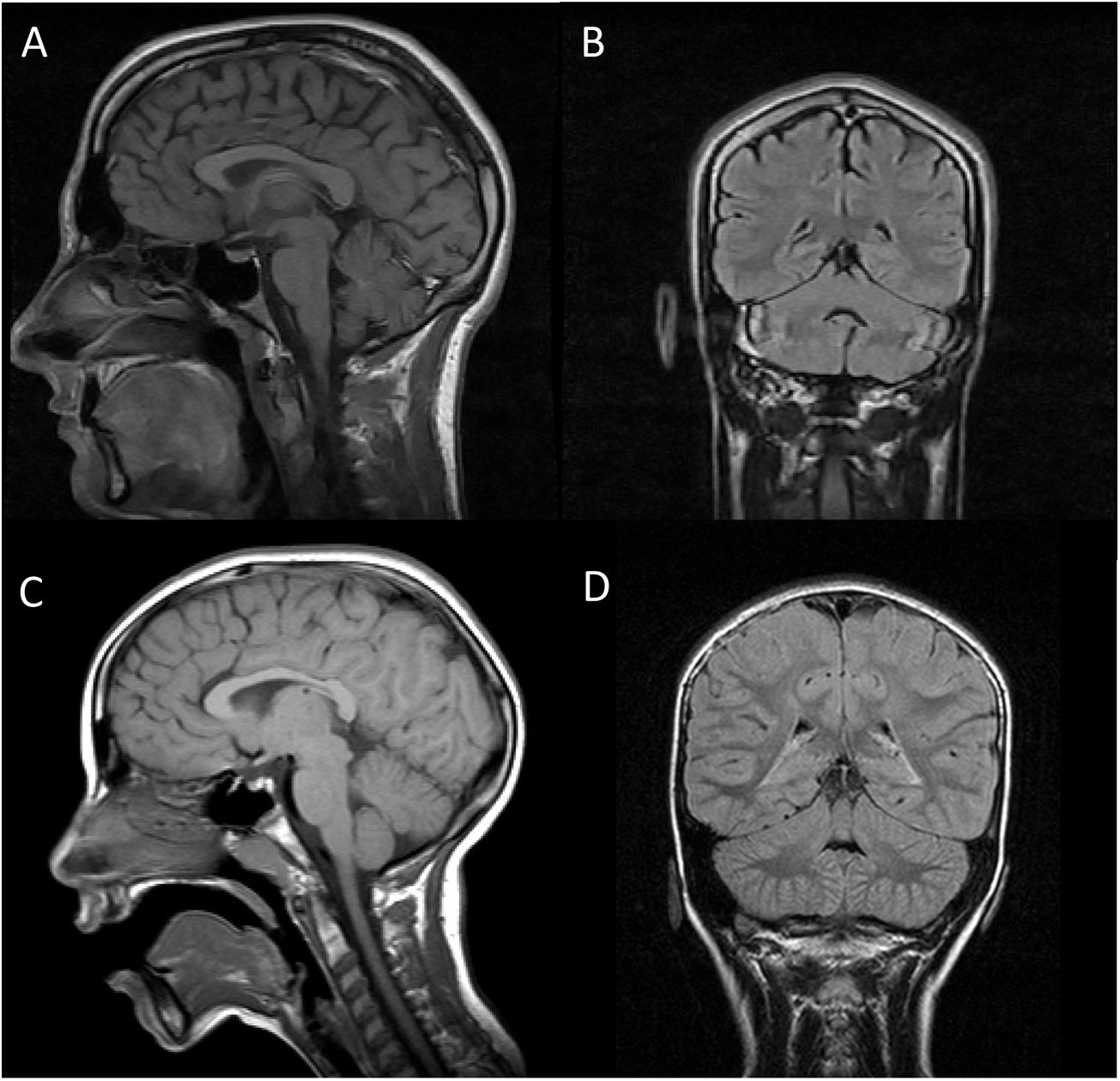

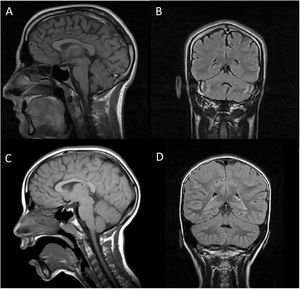

Both patients underwent brain (Fig. 1) and muscle MRI scans, electroencephalography, electromyography, electroneurography, and auditory evoked potentials studies, which yielded normal results, with the exception of slight atrophy of the vermis in patient 1. We screened for ARCAs potentially responsive to disease-modifying treatment, with negative results. We also performed a basic genetic study, including karyotyping, fragile X syndrome test, and an array CGH (60 K) study, finding no alterations. Finally, an ataxia panel revealed that both patients were homozygous carriers of variant NM_016955.3:c.1321 G > A; p.(Gly441Arg) in exon 11 of the SEPSECS gene; the variant was found in heterozygosis in both parents, and is considered pathogenic according to in silico prediction programmes.4 This missense mutation had previously been described in a patient with microcephaly and progressive cerebellar hypoplasia.4

Brain MRI scan of our 2 patients. A and C) T1-weighted sequence (sagittal plane). B and D) FLAIR sequences (coronal plane). Images A and B are from patient 1, and images C and D from patient 2. In both cases, MRI revealed no alterations in the brainstem or cerebellum, with absence of the typical signs of pontocerebellar hypoplasia, except for slight atrophy of the vermis in patient 1.

Pathogenic variants of the SEPSECS gene have been associated with pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 2D, an antenatal- or childhood-onset neurodegenerative disorder characterised by severe pontocerebellar atrophy, causing ataxia, chorea, hypotonia, nystagmus, microcephaly, spasticity, and cognitive impairment, with progressive cerebral and cerebellar atrophy.4–6 The clinical phenotype has recently been expanded with the description of milder, later-onset forms. It has been hypothesised that missense mutations, such as the one detected in our patients, may result in greater residual activity of the SepSecS protein, which may explain the later onset and milder severity.4

The SEPSECS gene, located at 4p15.2, catalyses the final step of selenocysteine synthesis. SEPSECS encodes the SepSecS protein, which gives rise to O-phosphoseryl-tRNA:selenocysteinyl-tRNA synthetase; this enzyme plays a key role in the only biosynthetic pathway for selenocysteine in eukaryotes and archaea.7 Selenocysteine is a selenoprotein that is particularly important in mammalian brain development.7

The clinical phenotypes of ARCAs frequently overlap, and present great variability. Diagnostic management should initially aim to determine whether the patient presents a type of ataxia for which an effective treatment is available, with a view to starting treatment as early as possible.2 This group includes recessive ataxias secondary to congenital metabolic defects (abetalipoproteinaemia, ataxia with vitamin E deficiency, etc).2 Once these disorders have been ruled out, diagnosis must be expanded based on the phenotype, considering the most frequent disorders (eg, Friedreich ataxia). According to the latest recommendations,1 a genetic study should subsequently be performed: initial testing should include studies of isolated genes (eg, Friedreich ataxia–associated trinucleotide repeat expansion in the FXN gene), followed by more complex techniques, such as next-generation sequencing, genetic panels, whole-exome sequencing, and even whole-genome sequencing.

In summary, we present the cases of 2 brothers with progressive cerebellar ataxia and no neuroimaging signs of atrophy, secondary to a SEPSECS mutation that until now had only been associated with pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 2D.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Martín Á, García-García J, Díaz-Maroto Cicuéndez I, Quintanilla-Mata ML, Segura T. Aportando luz en la oscuridad: ataxia cerebelosa autosómica recesiva por mutación en el gen SEPSECS. Neurología. 2022;37:709–710.