Headache is the most common neurological complaint at the different levels of the healthcare system, and clinical history and physical examination are essential in the diagnosis and treatment of these patients. With the objective of unifying the care given to patients with headache, the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Headache Study Group (GECSEN) has decided to establish a series of consensus recommendations to improve and guarantee adequate care in primary care, emergency services, and neurology departments.

MethodsWith the aim of creating a practical document, the recommendations follow the dynamics of a medical consultation: clinical history, physical examination, and scales quantifying headache impact and disability. In addition, we provide recommendations for follow-up and managing patients’ expectations of the treatment.

ConclusionsWith this tool, we aim to improve the care given to patients with headache in order to guarantee adequate, homogeneous care across Spain.

La cefalea es el motivo de consulta neurológico más prevalente en los distintos niveles asistenciales, donde la anamnesis y exploración son primordiales para realizar un diagnóstico y tratamiento adecuados. Con la intención de unificar la atención de esta patología, el Grupo de Estudio de Cefalea de la Sociedad Española de Neurología (GECSEN) ha decidido elaborar unas recomendaciones consensuadas para mejorar y garantizar una adecuada asistencia en Atención Primaria, Urgencias y Neurología.

MetodologíaEl documento es práctico, sigue el orden de la dinámica de actuación durante una consulta: anamnesis, escalas que cuantifican el impacto y la discapacidad y exploración. Además, finaliza con pautas para realizar un seguimiento adecuado y un manejo de las expectativas del paciente con el tratamiento pautado.

ConclusionesEsperamos ofrecer una herramienta que mejore la atención al paciente con cefalea para garantizar una asistencia adecuada y homogénea a nivel nacional.

Headache is one of the most frequent reasons for neurological consultation. Therefore, it is essential for physicians attending these patients to be proficient in its diagnosis and treatment.

Proper history-taking and examination are fundamental,1,2 given that correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment may be established from the first consultation, without needing to perform any complementary examination.

With a view to ensuring the proper medical care of patients with headache, unifying clinical practice, and guaranteeing healthcare equality for our patients, the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Headache Study Group (GECSEN) has established the following consensus recommendations, which are intended to facilitate systematic history-taking, examination, assessment, and follow-up of patients with headache.

A table is included to facilitate their use in the very different contexts in which patients with headache are attended: primary care, emergency departments, and neurology consultations. As with other publications, the study group’s Board invited young neurologists with experience in headache management to draft this consensus document, basing the recommendations on clinical experience and a review of the recent literature.

Medical historyMedical history should address the reason for consultation and the current disease (focusing on pain characteristics).3

Reason for consultationThe reason for consultation includes age, clinical course of the headache (focusing on onset and progression), and history of headache. Emergency departments should also record the reason for seeking emergency consultation.3

Current diseaseHistory-taking targeting pain characteristicsInitially, patients must be allowed to spontaneously describe the characteristics of their headache. This usually only takes 1-2 minutes.4,5 The next stage of history-taking should comprise a structured, targeted interview (Table 1) addressing the following aspects.6

Key points to be addressed in medical history interviews targeting pain characteristics.

| Temporal characteristics |

| Age at onset |

| Pain onset: sudden, gradual; time to peak |

| Frequency: daily, weekly, monthly; alternating attacks and remission |

| Duration: seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, years |

| Timeframe: morning, evening, night; fixed time; circadian rhythm; seasonal |

| Remission: sudden, progressive, persisting from onset |

| Quality |

| Pulsating, sharp, burning, lancinating, pressing |

| Intensity |

| Mild, moderate, intense |

| Incompatible with daily life |

| Nocturnal awakenings |

| Location |

| Focal, hemicranial, holocranial |

| Frontal, occipital, orbital, vertex pain; sensation of a band around the head |

| Changing location during progression |

| Triggering or exacerbating factors |

| Stress |

| Sleep pattern |

| Physical exercise |

| Hormonal factors (menstruation, contraception) |

| Diet, alcohol |

| Atmospheric changes |

| Valsalva manoeuvres (cough, intercourse) |

| Postural changes |

| Head movements |

| Pressure on a trigger point |

| Attenuating factors |

| Medication, rest/sleep, decubitus positions |

| Accompanying symptoms and time of onset (before/simultaneous with/after pain) |

| Nausea/vomiting |

| Phono-/photo-/osmophobia |

| Photopsia, scotoma, hemianopsia, diplopia |

| Hemiparesis/hemidysaesthesia |

| Instability, vertigo |

| Aphasia |

| Dysautonomic symptoms |

| Confusion/seizures/fever |

| Constitutional symptoms/jaw claudication |

It is crucial to know whether onset was sudden or insidious and, through analysing the progression of headache, whether the process is acute (< 72 hours), subacute (72 hours to 3 months), or chronic (> 3 months). We must evaluate the duration of the attack and whether pain is continuous and/or paroxysmal; in the latter case, we must establish the approximate duration. Disease progression is one of the most helpful characteristics in differential diagnosis. Pain frequency also guides assessment of the patient’s level of disability and the type of treatment to be indicated. Finally, some headaches, such as cluster headache, show a clear circadian pattern.

Pain qualityPulsating (throbbing)/pressing (tightening)/stabbing (puncture-like), sharp (perforating)/electric-shock–like.

Pain is usually perceived as pulsating in migraine, pressing in tension-type headache, sharp in cluster headache, burning and continuous in epicranial neuralgias, and electric-shock–like in neuralgias involving major trunks and in short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT)/short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with autonomic symptoms (SUNA). However, pain quality is not decisive in diagnosis, and careful attention must be paid to the remaining pain characteristics. In many cases, patients do not apply any of these descriptors to their pain.6

IntensityNumeric pain rating scale7: 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain). Scores of 1-3 are considered mild, 4-6 moderate, and 7-10 severe.

As pain and pain intensity are subjective, it is important to assess progression with intra-subject measures. It should also be noted that, with the exception of thunderclap headache, pain intensity usually does not correlate with the severity of the underlying cause.8

Location- ◦

Circumscribed/unilateral/holocranial/nerve territory

- ◦

Radiating

Patients should be asked to precisely indicate the site of pain onset and its potential radiation to nearby areas, as well as variation or migration to other areas of the face, head, or neck. For example, pain that appears and remains on one side of the head, never crossing the midline, may be considered differently to pain initiating in the same way but that changes sides or extends to the whole head; pain circumscribed to a circular or elliptical area or coinciding with the territory of a specific nerve should also be considered differently.6

Triggering or exacerbating factorsCluster headache may be triggered by alcohol or vasodilator drugs. Valsalva manoeuvres trigger or exacerbate secondary headaches, as well as certain primary headaches, such as those associated with cough, physical exercise, or intercourse. Hypnic headache exclusively appears during sleep. Low cerebrospinal fluid pressure headache typically occurs when standing, and improves with decubitus positions, unlike headache due to intracranial hypertension. Head movement exacerbates pain in such headaches as migraine and cervicogenic headache. Palpation of the emergence of the terminal branches may trigger attacks of neuralgia in the corresponding areas.

Attenuating factorsAttenuating factors are those that relieve pain, such as the type of treatment, treatment response, or head position; these may also guide us in identifying the type of headache. For example, response to indometacin is indicative of hemicrania continua, and decubitus positions typically alleviate headache secondary to intracranial hypotension.

Accompanying symptomsPhono-/photophobia and nausea are common symptoms during migraine attacks, although they may also appear in secondary headaches. Osmophobia and gustatory alterations may be even more specific to this type of headache.9 Diagnostic certainty is greater in patients presenting transient focal symptoms (scotoma; fortification spectrum; progressive, self-limited sensory or language syndromes) compatible with typical migraine aura or such premonitory symptoms as asthenia, neck stiffness, hyperphagia, or yawning.10,11 We should also enquire about oculofacial autonomic signs and symptoms ipsilateral to pain: in the correct clinical context, this guides the diagnosis of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, although these symptoms have also been described in association with migraine-type headache. Secondary headaches may also be accompanied by focal neurological signs, altered level of consciousness, fever, or seizures. Intracranial hypertension may manifest with tinnitus or temporary darkening of vision. Giant cell arteritis may be associated with constitutional and rheumatological symptoms or jaw claudication.

Secondary headache should initially be ruled out based on the signs and/or symptoms of pain itself, as well as the clinical characteristics associated with headache (Table 2).

Warning signs and symptoms of secondary headache.

| Type of warning sign/symptom | |

|---|---|

| Pain characteristics | Sudden or explosive onset, with or without associated effort or Valsalva manoeuvre |

| Recent onset with progressive increase in intensity or frequency | |

| Recent, considerable change in characteristics of previous headache | |

| Progressive increase in intensity/frequency and loss of response to previously effective analgesics | |

| Clear, consistent worsening with postural changes | |

| Nocturnal awakenings due to headache | |

| Strictly unilateral location | |

| Clinical characteristics | Age of onset > 50 years, especially if associated with rheumatic symptoms, jaw claudication, or constitutional syndrome |

| Presence of neoplasia and/or immunosuppression | |

| Increased risk of haemorrhage (eg, in patients receiving anticoagulants) | |

| Association with fever without focus, especially in patients with meningeal syndrome | |

| Vomiting not attributable to primary headache (migraine), or projectile vomiting | |

| Focal neurological signs | |

| Headache associated with seizures | |

| Visual alterations suggestive of papilloedema |

However, certain signs and symptoms can be associated with both primary and secondary headache (Table 3).

Signs and symptoms that may be associated with both primary and secondary headaches.

| Sign/symptom | Primary headache | Secondary headache |

|---|---|---|

| Pulsating pain, worsening with Valsalva manoeuvres, nausea and/or vomiting | Migraine | Meningitis |

| Hypertensive crisis/PRES | ||

| Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis | ||

| Atypical visual aura | Migraine with aura | Stroke |

| HaNDL syndrome | ||

| Ptosis, miosis | Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia | Carotid artery dissection |

| Cavernous sinus syndromes | ||

| Orbital pain, red eye, pupillary alterations | Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia | Angle-closure glaucoma |

| Uveitis | ||

| Cavernous sinus syndromes | ||

| Holocranial, pressing pain of mild to moderate intensity | Tension-type headache | Highly non-specific. Multiple processes |

| Pain in temporal region | Myofascial syndrome | Temporal arteritis |

| TMJ disorders | ||

| Exclusively nocturnal awakenings due to headache | Hypnic headache | Nocturnal hypertension |

HaNDL: transient headache and neurological deficits with cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis; PRES: posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome; TMJ: temporomandibular joint.

Adapted from Irimia.3

This part of the medical history interview should address the following areas (Table 4):

Key points to be addressed in targeted medical history interviews with patients with headache.

| Personal history |

| Medication allergies |

| Vascular risk factors |

| Drug habits |

| Craniofacial disorders (TMJ disorders, etc) |

| Heart disease/asthma/nephrolithiasis/glaucoma |

| Mood alterations |

| Sleep alterations (drowsiness, insomnia, bruxism, SAHS) |

| Head trauma |

| Phase in the menstrual cycle, oral contraceptives |

| Family history |

| Social factors |

| Type of work/shifts |

| Number of children and socioeconomic situation |

| Factors affecting headache transformation |

| Medication overuse |

| Body mass index |

| Mood alterations |

| Sleep cycle alterations |

| Caffeine consumption |

| Chronic stress |

| Sedentary lifestyle |

| Medication |

| Current or previous treatments |

| Maximum dose reached/duration |

| Effectiveness/adverse reactions |

SAHS: sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome; TMJ: temporomandibular joint.

It is important to gather information about the patient’s clinical history, as some health conditions, such as sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome, may play a role in headache. The patient’s history may also influence the treatments we can use, as some drugs may exacerbate underlying conditions (for instance, flunarizine can exacerbate depression and may cause weight gain). In other cases, we may be able to select a treatment with a dual effect; for example, in hypertensive patients, we may use beta-blockers, lisinopril, or candesartan to treat headache.

Family history of headacheWe should ask about family history of headaches resembling the patient’s, particularly among close relatives. Migraine is an example of a primary headache that can affect several members of the same family, with hereditability estimated at 40% to 60% (higher levels in migraine with aura); therefore, family members of patients with migraine present higher risk than the general population.12 Tension-type headache, and especially chronic forms, also tends to aggregate in families.13 Many patients with cluster headache report family history of headache, including migraine, with increased risk among first-degree relatives.14

Social factorsWe must determine whether any current or previous conflict or stressful situation may be triggering headache, particularly chronic headache. Personal, family, social, or work-related problems can occasionally play a role in the form of presentation of headache.6 Pain may also cause considerable disability; we should therefore enquire about this possibility and its potential impact on patients’ mood and cognitive performance.

Factors affecting headache transformationPhysicians should enquire about factors potentially leading to changes in pain frequency, and even chronic headache.15,16 The most frequent risk factors are listed in Table 4.

MedicationIt is helpful to determine what drugs the patient has used to control headache, and which were the most and the least effective (it is also important to record the maximum dose reached and the actual duration of treatment). We should also consider whether headache may be caused by some drug the patient is using. Drugs liable to worsen the clinical course of migraine include those used for hormone replacement therapy and oral contraception, vitamin A, and retinoic acid derivatives. Both migraine and cluster headache may be exacerbated by the use of such vasodilators as nitrites, minoxidil, and nifedipine. Chronic use of medications including opiates, barbiturates, caffeine, ergotamines, or a combination of these may cause rebound or withdrawal headache.17 It is also important to enquire about the use of oral anticoagulants, given the risk of secondary headaches or with a view to performing procedures during the consultation.

Recommended scalesThe instruments we recommend are self-administered questionnaires with validated Spanish-language versions that may be used for adult patients and for both clinical and research purposes. They aim to quantify disability, headache impact, comorbidities, and other variables of interest, as well as symptom improvement and worsening.

Disability assessmentThe Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire18 is broadly validated and has been translated into multiple languages. It comprises 5 items evaluating the impact of headache on work/school performance, domestic work, and social activities over a 3-month period. The total score indicates the patient’s grade of disability, from I to IV. Grade IV was recently subdivided into grades IVa and IVb in order to better characterise the disability associated with chronic migraine.

Another tool for measuring the functional impact of headache is the 6-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6).19 The scale assesses the frequency of severe pain, limitations in daily activities (including work, school, and social activities), desire to lie down, fatigue, irritability, and difficulty concentrating. It is also useful for assessing treatment response: a reduction of 2 or 3 points after 4 weeks of treatment is correlated with clinically significant improvement. It can also be used to evaluate patients with chronic migraine or chronic daily headache.

Finally, the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI),20 including 6 items, assesses limitations in everyday activities and performance at work. While this scale was not designed specifically for patients with headache or pain, an adapted version was created for this purpose.

Quality of life assessmentIn addition to the reduction in disability, improvements in quality of life are also used to evaluate patients’ response to certain treatments and interventions. The Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ)21 is ideal for assessing limitations on quality of life and treatment effectiveness. It evaluates the impact of migraine on 3 domains: socialising, work-related activities, and emotions related to migraine. In version 2.1, the content of the questionnaire was improved for greater clarity, and it was shortened to improve its ease of administration.

While it is not specific to migraine, the most widely used instrument for assessing quality of life is the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36),22 which addresses physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health. It includes 36 questions addressing patients’ experience over the previous 4 weeks. An abbreviated version, the SF-12,23 covers all 8 domains but does not provide specific scores for each.

Another widely used scale, which is also not specific to migraine, is the European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire,24 which evaluates health-related quality of life. The first part of the questionnaire includes 5 questions covering 5 dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), and the second is a visual analogue scale on which the patient is asked to rate their health from 1 to 100.

Assessment of psychiatric comorbiditiesIt is useful to have tools for screening or assessing the need to treat psychiatric disorders associated with headache. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)25 is a widely used screening tool comprising 14 items: 7 assessing anxiety (HADS-A) and 7 assessing depression (HADS-D). Scores are classified as normal, borderline, or abnormal.

Regarding depressive symptoms, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)26 is a 21-item questionnaire covering all the diagnostic criteria for depression listed in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and is the most indicated instrument for assessing the severity of depression. Each item is scored from 0 to 3, and the total score is divided into 4 categories: absent or minimal, mild, moderate, or severe. The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)27 may be useful for diagnosing depressive symptoms and for monitoring their intensity and treatment response. It includes 9 items scored from 0 to 3; patients are classified as having no depression, minor depressive disorder, or major depressive disorder, according to their total score.

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)28 measures the presence and severity of symptoms of anxiety. It includes 2 subscales comprising 20 questions each: the state subscale addresses the patient’s current state (“at this moment”), whereas the trait subscale focuses more on trends (“generally”). Finally, the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)29 is useful for screening for anxiety: this 21-item questionnaire assesses somatic symptoms of the condition.

Other instrumentsWhen evaluating a patient with headache, we may wish to quantify other symptoms or comorbidities potentially influencing the patient’s functional status. While reviewing all such scales is beyond the scope of the present study, Table 5 includes some of the most useful.30–35

Characteristics of the main self-administered scales for assessing patients with headache.

| Use | Disease | No. items | Administration time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disability | ||||

| MIDAS | Workplace, home, social | Migraine | 5 (+2) | < 5 min |

| HIT-6 | Everyday activities | Migraine | 6 | < 5 min |

| WPAI | Everyday and workplace activities | Non-specific | 6 | < 5 min |

| Quality of life | ||||

| MSQ | Quality of life limitations | Migraine | 14 | 5 min |

| SF-36 | General health status | Non-specific | 36 | 10 min |

| SF-12 | General health status | Non-specific | 12 | < 5 min |

| EQ-5D | Health-related | Non-specific | 6 | < 5 min |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | ||||

| HADS | Anxiety/depression screening | Non-specific | 14 | < 5 min |

| BDI-II | Degree of depression | Non-specific | 21 | 5-10 min |

| PHQ-9 | Depression screening and degree | Non-specific | 9 | < 5 min |

| STAI | Degree of anxiety | Non-specific | 40 | 10 min |

| BAI | Anxiety screening | Non-specific | 21 | 5-10 min |

| Other | ||||

| Short IPAQ | Physical activity | Non-specific | 9 | 5-10 min |

| PSQI | Sleep quality | Non-specific | 19 | 5-10 min |

| ISI | Insomnia | Non-specific | 5 | < 5 min |

| PSS | Self-perceived stress | Non-specific | 14 | 5-10 min |

| ASC-12 | Allodynia | Migraine | 12 | 5 min |

| CAPS | Autonomic symptoms | Migraine | 5 | < 5 min |

ASC-12: Allodynia Symptom Checklist; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory; CAPS: cranial autonomic parasympathetic symptoms; EQ-5D: European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HIT-6: Headache Impact Test; IPAQ: International Physical Activity Questionnaire; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; MIDAS: Migraine Disability Assessment; MSQ: Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire; PHQ-9: 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; SF: Short Form; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; WPAI: Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire.

Patient examination should be systematic and include both a general neurological examination and a specific examination of the head (Table 6).

Key procedures in the examination of patients with headache.

| General examination |

| Head and facial examination |

| Ophthalmoscopy |

| Inspection |

| Trophic/colouration changes |

| Trigeminal autonomic signs |

| Palpation |

| Allodynia; areas of hyper-/hypoalgesia |

| Pericranial nerves: supra-/infraorbital, GON, LON, mental, supra-/infratrochlear; lacrimal, auriculotemporal |

| Tenderness test |

| Trochlear region |

| Paranasal sinuses |

| Craniocervical muscles: assess trigger points |

| Temporomandibular joint |

| Temporal pulse |

| Cervical flexion-rotation test |

GON: greater occipital nerve; LON: lesser occipital nerve.

Special attention should be paid to signs that may present with secondary headache, such as meningeal signs or focal neurological signs.

Head and facial examinationOphthalmoscopyOphthalmoscopy should always be performed. It is particularly important to identify the optic disc, which measures approximately 1.5 cm and is located to the nasal side and appears pale pink in colour, with a rounded shape and well-defined edges. The emergence of vessels and venous pulsation should be evaluated, and any exudate or haemorrhage identified.

Optic disc oedema or pallor should also be assessed. While the term papilloedema refers specifically to inflammation of the optic disc secondary to increased intracranial pressure, oedema of the optic disc may also be caused by other factors. Cases have also been described of intracranial hypertension syndrome without papilloedema.36 Presence of venous pulsation is an additional sign indicating intracranial pressure below 20 cm H2O.

InspectionDuring the inspection, we must assess changes in colouration or trophic changes (eg, in patients with nummular headache) and establish the presence of trigeminal autonomic signs, such as ocular hyperaemia, tearing, ptosis, miosis, or rhinorrhoea. Examination may reveal findings that are not completely specific but are highly suggestive, such as asymmetrical findings in patients with hemicrania continua.

Palpation- •

Cranial allodynia should be assessed with gentle palpation of the parietal region. Subsequently, different symmetrical points on both sides of the head should be compared to identify areas of increased sensitivity or hyperalgesia.

- •

Pericranial nerves: diffuse cranial allodynia must always be ruled out first. The areas most frequently evaluated are:

Supraorbital nerve: emerges from the supraorbital foramen, in the medial third of the superciliary arch.37

Infraorbital nerve: follows a straight line on the vertical plane along the zygomatic arch from the supraorbital area.38

Greater occipital nerve: on an imaginary line from the occiput to the mastoid process, the nerve emerges where the middle third meets the medial third. It is usually easy to determine the course of the nerve by applying firm pressure along this imaginary line and asking the patient to locate the most painful area.39

Lesser occipital nerve: located laterally to the greater occipital nerve.

Others: mental nerve, supra- and infratrochlear nerves, lacrimal nerve, and auriculotemporal nerve.40

During palpation, one or 2 fingers (generally the second and third) should be used for support, while increasing pressure is applied along the course of the nerve. This support is important to prevent the finger from slipping into the eye. One clinical detail that often indicates hypersensitivity of a nerve is the jump sign, whereby the patient will wince and move the head/body to pull away from the pressure. It is also important to be aware that pressure applied to a nerve will cause an unpleasant and even painful sensation, even in healthy individuals. This part of the examination also provides the opportunity to evaluate such treatment options as anaesthetic nerve block.41

- •

Tenderness test: this test is mainly used for tension-type headache, and enables us to establish the presence of pericranial hypersensitivity.

- •

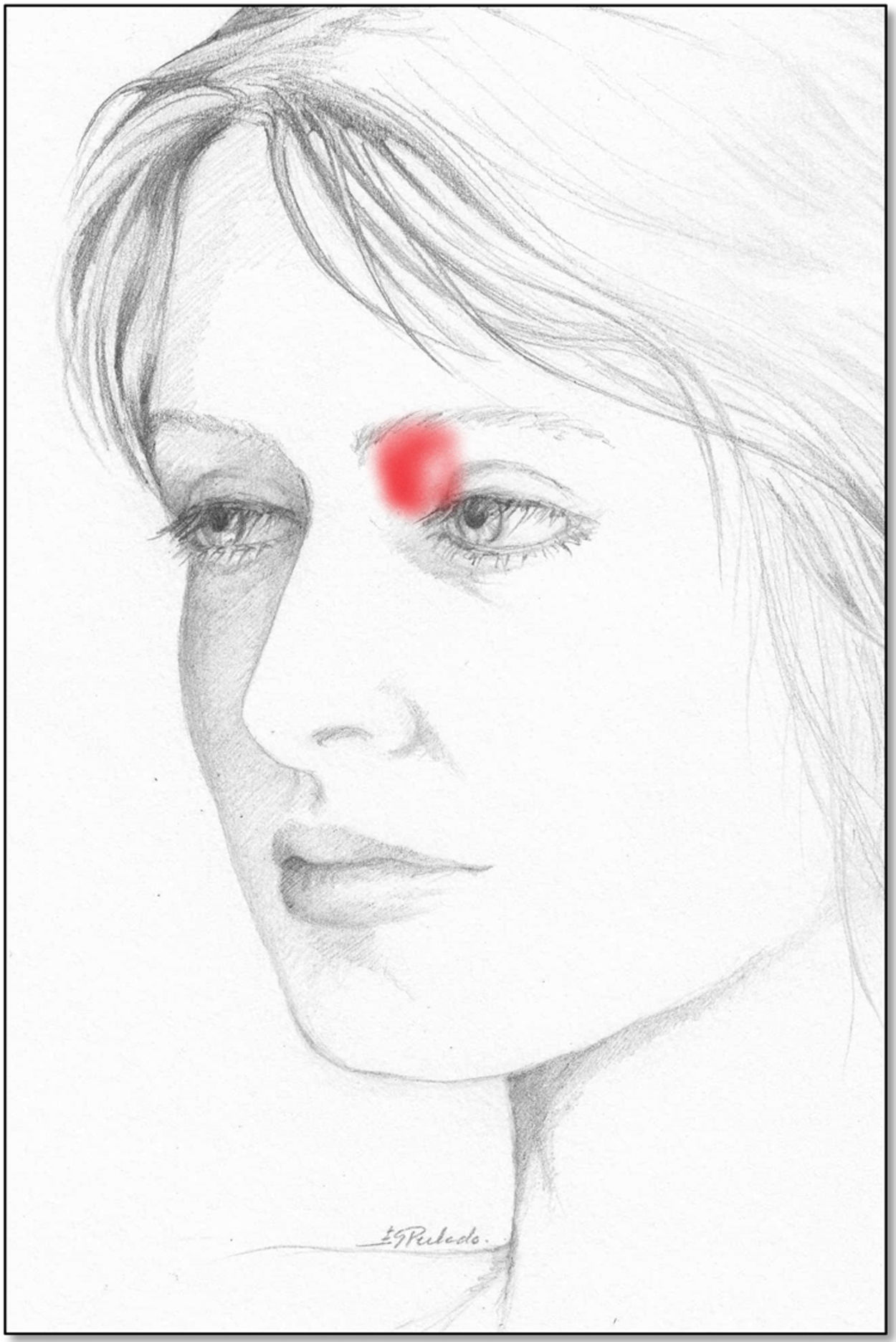

Trochlear region: located above the lacrimal caruncle, between the eye and the frontal bone (Fig. 1). Palpation should be used to ascertain the existence of clear hypersensitivity, which is typically exacerbated by vertical movement of the eye (which involves the superior oblique muscle). It should be noted that trochleitis is defined as the inflammation of this region, and specifically the trochlea of the superior oblique nerve; trochleodynia refers to the typical pain in this region without inflammation.

- •

Paranasal sinuses: during palpation of the paranasal sinuses, we must bear in mind that the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves run close to this area; the pain evoked in these nerves is much more focal.

- •

Palpation of the main craniocervical muscles: it is essential to search for trigger points, or hyperirritable spots in the muscle, which may cause local pain or a pattern of referred pain when the muscle is active. Tender points (areas in which palpation provokes intense pain) are identifiable by a clear tendency to recoil.42 Patients with temporomandibular joint disorders often present trigger points in the masseter and muscles of the temporal area. In these patients, clicking sounds and pain upon palpation of the temporomandibular joint and disproportionate wear of the cusps of the teeth should alert us to the possibility of temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome.

- •

Bilateral palpation of the temporal pulse: this is important in elderly patients with suspected temporal arteritis.

This test should be performed in patients with predominantly posterior headache. From behind the seated patient, the examining physician must flex the patient’s neck vertically by around 10°, then rotate the head on the horizontal plane to determine whether the patient is able to rotate the head by at least 70° in both directions. Absence of asymmetry or reproduction of the pain that led the patient to consult can reasonably be considered to rule out cervicogenic headache.

Recommendations for patient education, expectation management, and follow-upAfter the pharmacological treatment has been explained, clear instructions should be given to track pain at home with the use of headache calendars and diaries; patient education should also be provided to resolve any questions and manage patients’ expectations.

Headache calendars and diariesThe difference between these tools is that while headache diaries record the semiology of each episode in greater detail, and are mainly useful in early stages of assessment, calendars track the chronological distribution of episodes, and help in identifying aggravating factors and evaluating the effectiveness of preventive treatments without risk of recall bias.43–45

The key points to be recorded are:

- ◦

Pain days, indicating intensity (mild/moderate/severe)

- ◦

Disability days

- ◦

Symptomatic treatment days (number of pills)

- ◦

Menstruation.

This information may be noted on a paper record (which is not always available, potentially leading to less complete data or forgotten days) or electronically. Advances in information technology have led to the creation of digital tools specifically designed to be used simultaneously by patients and physicians.46 Specific diaries have also been designed to improve the semiological description of migraine aura and postdromic symptoms.47,48 While they are of limited clinical value, and patients must be instructed in their use, they can be helpful in the differential diagnosis of doubtful cases. These tools also allow for better communication between physician and patient.49–51

Patient educationSeveral studies have shown that behavioural interventions are well accepted by patients52; interventions aiming to improve lifestyle and adherence to preventive treatment are associated with better clinical outcomes.53Table 7 shows some standard recommendations to help in the education of patients with headache.

Education measures for patients with migraine and other primary headaches.

| General measures | Stress |

| Avoidance of trigger factors | Relaxation techniques |

| Avoidance of irritating stimuli | Biofeedback |

| Minimal use of screens | Behavioural interventions |

| Prevention of brain trauma | Cognitive-behavioural therapy |

| Sleep | Physical exercise |

| Regular sleep pattern | Increased baseline activity level |

| 8 h’ sleep per day | Aerobic exercise |

| Dinner 4 h before bed | Moderate intensity |

| Avoidance of fluids for 2 h before bed | Regular frequency |

| Elimination of naps | Adapted to physical fitness |

| Avoidance of screens in bed | Progressive onset |

| Visualisation techniques | Proper hydration |

| Diet | Overweight and obesity |

| Balanced, varied, moderate diet | Dietary interventions |

| 5 meals per day | Physical exercise |

| Avoidance of prolonged fasting | Behavioural therapy |

| 2.5 L water/day | Evaluation of pharmacological treatments |

| No more than 2 coffees per day on a regular basis | Evaluation of bariatric surgery |

| Minimal alcohol consumption | Avoidance of drugs that can cause weight gain |

| Acute treatment | Preventive treatment |

| Individualised | Non-pharmacological measures |

| Early | Compliance with daily regime |

| Appropriate administration route | Effectiveness to be assessed at 3 months |

| Additional dose in event of recurrence | Treatment to be maintained for 6-12 months |

| Treatment of accompanying symptoms | Notification of potential adverse effects |

| Emergency department visit if pain is refractory to treatment | Contact with medical team |

| Avoidance of opioids and combinations of drugs | |

| Avoidance of symptomatic medication overuse |

Adapted from Torres-Ferrus and Pozo-Rosich.55

As well as empowering patients, new technology has enabled them to improve their self-care. The perceived benefits to patients of applications and websites for the follow-up of chronic headache include better self-awareness, the ability to share data with physicians and to review historical data, and better control of their disorder.54

Many online resources with patient information are available in English, although some Spanish-language resources also exist. Such resources include:

Mobile applications including calendars, such as MyMigraines and MyMigraines Pro (Guerrero-Peral and colleagues), which also offer the possibility for the patient’s neurologist to view the data in real time; and MigraineBuddy, which also assists in identifying potential trigger factors including atmospheric changes in the patient’s location.

The website midolordecabeza.org (Pozo-Rosich and colleagues) is aimed both at patients and at professionals, and allows for the creation of calendars, the application of scales for follow-up (data may be sent to the physician to optimise history-taking in consultations), a forum for sharing experiences, and a blog with relevant news, run by specialists. It also provides information on access to research projects.

The websites neurodidacta.es and neurowikia.es also provide information for patients and physicians on headache and other neurological disorders.

ConclusionsRigorous, systematic history-taking and examination are essential in the diagnosis and treatment of headache, particularly given that complementary examinations are not diagnostic, and are only able to diagnose some secondary headaches. The training of primary care and emergency department physicians, as well as neurologists, is not always appropriate. Although these recommendations are no substitute for a rotation at a headache unit, we hope they will provide basic tools for performing holistic, targeted patient interviews, systematising and unifying the care provided to patients with headache at the national level.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Esperanza González Perlado for her beautiful drawing.

Please cite this article as: Gago-Veiga AB, Camiña Muñiz J, García-Azorín D, et al. ¿Qué preguntar, cómo explorar y qué escalas usar en el paciente con cefalea? Recomendaciones del Grupo de Estudio de Cefalea de la Sociedad Española de. Neurología. 2022;37:564–574.