Ischaemic stroke is the most common neurological complication of cardiac catheterisation. This study aims to analyse the clinical and prognostic differences between post-catheterisation stroke code (SC) and all other in-hospital and prehospital SC.

MethodsWe prospectively recorded SC activation at our centre between March 2011 and April 2016. Patients were grouped according to whether SC was activated post-catheterisation, in-hospital but not post-catheterisation, or before arrival at hospital; groups were compared in terms of clinical and radiological characteristics, therapeutic approach, functional status, and three-month mortality.

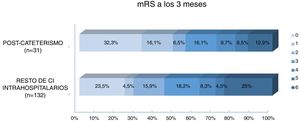

ResultsThe sample included 2224 patients, of whom 31 presented stroke post-catheterisation. Baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was lower for post-catheterisation SC than for other in-hospital SC and pre-hospital SC (5, 10, and 7, respectively; P=.02), and SC was activated sooner (50, 100, and 125minutes, respectively; P<.001). Furthermore, post-catheterisation SC were more frequently due to transient ischaemic attack (38%, 8%, and 9%, respectively; P<.001) and less frequently to proximal artery occlusion (17.9%, 31.4%, and 39.2%, respectively; P=.023). The majority of patients with post-catheterisation strokes (89.7%) did not receive reperfusion therapy; 60% of the patients with proximal artery occlusion received endovascular treatment. The mortality rate was 12.95% for post-catheterisation strokes and 25% for all other in-hospital strokes. Although patients with post-catheterisation stroke had a better functional prognosis, the adjusted analysis showed that this effect was determined by their lower initial severity.

ConclusionsPost-catheterisation stroke is initially less severe, and presents more often as transient ischaemic attack and less frequently as proximal artery occlusion. Most post-catheterisation strokes are not treated with reperfusion; in case of artery occlusion, mechanical thrombectomy is the preferred treatment.

El ictus es la complicación neurológica más frecuente tras una coronariografía. Nuestro objetivo fue estudiar las diferencias clínicas y pronósticas entre los códigos ictus (CI) poscateterismo y el resto de CI intra y extrahospitalarios.

MétodosRegistro prospectivo de activación de CI entre marzo de 2011 y abril de 2016 en nuestro centro. Comparamos características clínicas, radiológicas, tratamiento administrado, situación funcional y mortalidad a 3 meses dependiendo de si se trató de un CI poscateterismo, del resto de CI intrahospitalarios o extrahospitalarios.

ResultadosDe 2.224 activaciones de CI 31 fueron poscateterismo. Los CI poscateterismo presentaron una NIHSS basal menor respecto al resto de CI intrahospitalarios y extrahospitalarios (5 vs. 10 vs. 7 respectivamente, p=0,02), mayor rapidez en la activación (50min vs. 100min vs. 125min, p<0,001), mayor presentación en forma de AIT (38% vs. 8% vs. 9%, p<0,001) y menor tasa de oclusión arterial proximal (17,9% vs. 31.4% vs. 39.2%, p=0,023). El 89,7% de ictus poscateterismo no recibieron tratamiento de reperfusión. En caso de oclusión arterial proximal el 60% recibió tratamiento endovascular. La mortalidad fue del 12,95% en los CI poscateterismo y del 25% en el resto de CI intrahospitalarios. Aunque los ictus poscateterismo presentaron mejor pronóstico funcional, el análisis ajustado mostró que este efecto estaba determinado por su menor gravedad inicial.

ConclusionesEl ictus poscateterismo tiene una menor gravedad inicial, aparece más frecuentemente como AIT y presenta menor incidencia de oclusión arterial proximal. La mayoría no recibe tratamiento de reperfusión, pero cuando existe oclusión arterial, la mayor parte de ellos son tratados mediante trombectomía.

Ischaemic stroke is the most frequent neurological complication of cardiac catheterisation, with an estimated incidence of 0.05%-0.1% in patients undergoing diagnostic coronarography and 0.18%-0.44% in those undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.1 Stroke may have devastating consequences in this context, resulting in high mortality rates (22%-37%).1 The risk factors of post-catheterisation stroke are well characterised in large patient series. Older patients with chronic kidney disease and vascular risk factors have been shown to present a greater risk of stroke during or after prolonged emergency catheterisation procedures.2

For many years, stroke treatment in these patients has been controversial since heparin sodium infusion during angiography procedures is associated with a twofold increase in the risk of haemorrhage following systemic fibrinolysis,3–6 the only approved treatment until 2015. Arterial revascularisation with mechanical thrombectomy may represent a safe, effective option for patients with acute large-vessel occlusion.

Given that we are now able to offer these patients acute reperfusion treatment, it is essential to deepen our knowledge of the differentiating characteristics and functional prognosis of post-catheterisation stroke. The purpose of this study was to compare the clinical, radiological, and therapeutic characteristics of patients with post-catheterisation stroke and those with other types of stroke (both in-hospital and pre-hospital strokes), and to analyse differences in functional prognosis between patients with post-catheterisation stroke and patients with other types of in-hospital stroke.

Material and methodsStudy populationThe Barcelonés Nord and Maresme health district includes both rural and urban areas, with a total population of 705803 and an area of 463km2. It has 21 emergency medical service bases, 4 district hospitals, and a stroke reference hospital (Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol), which also serves a population of 2000000 as a tertiary-level centre for endovascular treatment.

Code stroke is activated when patients present neurological symptoms compatible with stroke of less than 8hours’ progression or unknown progression time, and in patients with wake-up stroke and known functional dependence (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score ≤ 2), regardless of age.

This study is based on our prospective registry, which includes data from all code stroke activations since March 2011. The registry prospectively gathers demographic data, the timeline of the episode, type of code stroke activation, baseline clinical and radiological characteristics, treatment administered, and diagnosis according to the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project (OCSP) classification.7

We included all cases of code stroke activations occurring between March 2011 and April 2016. All patients were evaluated by a neurologist and treated according to the European guidelines.8,9 Patients with ischaemic stroke of less than 4.5hours’ progression received systemic fibrinolysis with alteplase. In cases of contraindication to intravenous alteplase10 or failure of thrombolytic therapy, endovascular treatment was considered in patients with large-vessel occlusions (middle cerebral artery, intracranial carotid artery, tandem occlusion, basilar artery) of less than 8hours’ progression.11

Study variablesData were gathered on demographic variables (age and sex), time from symptom onset to code stroke activation, type of code stroke activation (in-hospital or pre-hospital), previous functional status (mRS), and stroke severity (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS]) at admission. Strokes were classified as post-catheterisation strokes (occurring within 24hours of the procedure), other in-hospital strokes, or pre-hospital strokes. The Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) was used to evaluate the presence of early signs of ischaemia on head CT or brain MRI studies performed at admission,12 and the presence and location of artery occlusion were determined using CT angiography, MRI angiography, or transcranial Doppler ultrasound. Data were also recorded on diagnosis according to the OCSP classification and the reperfusion treatment administered during the acute phase (systemic fibrinolysis, primary or rescue endovascular treatment, or no reperfusion treatment).

Follow-up and outcome measuresThe mRS was used to evaluate functional status at 3 months during follow-up neurological consultations exclusively for patients with in-hospital stroke. Scores ≤ 1 are considered to indicate excellent prognosis, with scores ≤ 2 indicating good prognosis. In patients who were deceased at 3 months, we recorded the cause of death to determine whether it was secondary to the cerebrovascular event.

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and the 25th and 75th percentiles (p25-p75), and categorical variables as frequencies. We compared the 3 subgroups (post-catheterisation stroke, other in-hospital strokes, pre-hospital stroke) using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables, and the chi-square test for categorical variables. We provide 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P values for all effect size estimates; statistical significance was set at P<.05. For the multivariate analysis of factors associated with good prognosis and mortality, we performed a logistic regression analysis including the variables showing a P value < .05 in the univariate analysis. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 23 (IBM; Chicago, IL, USA).

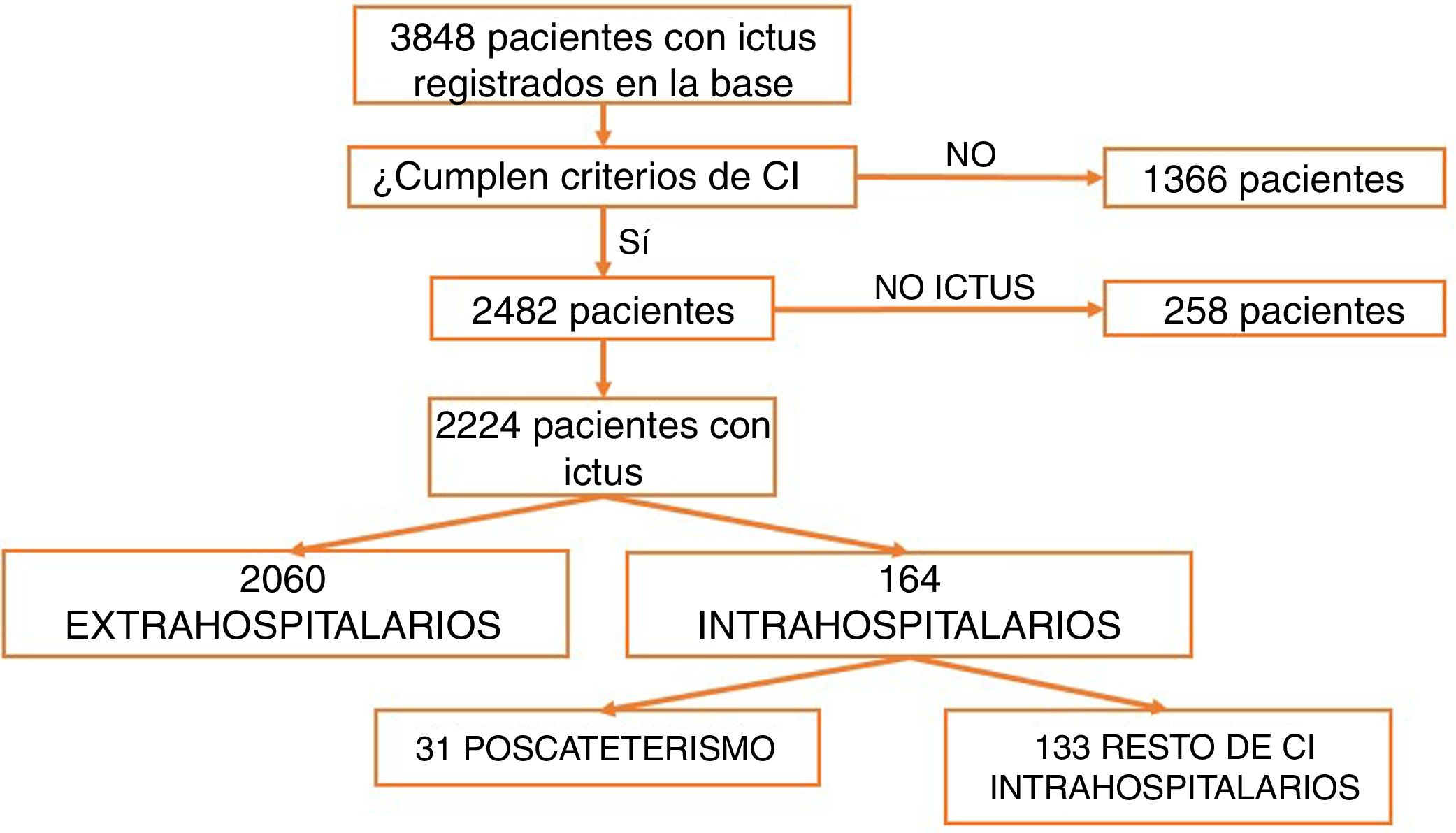

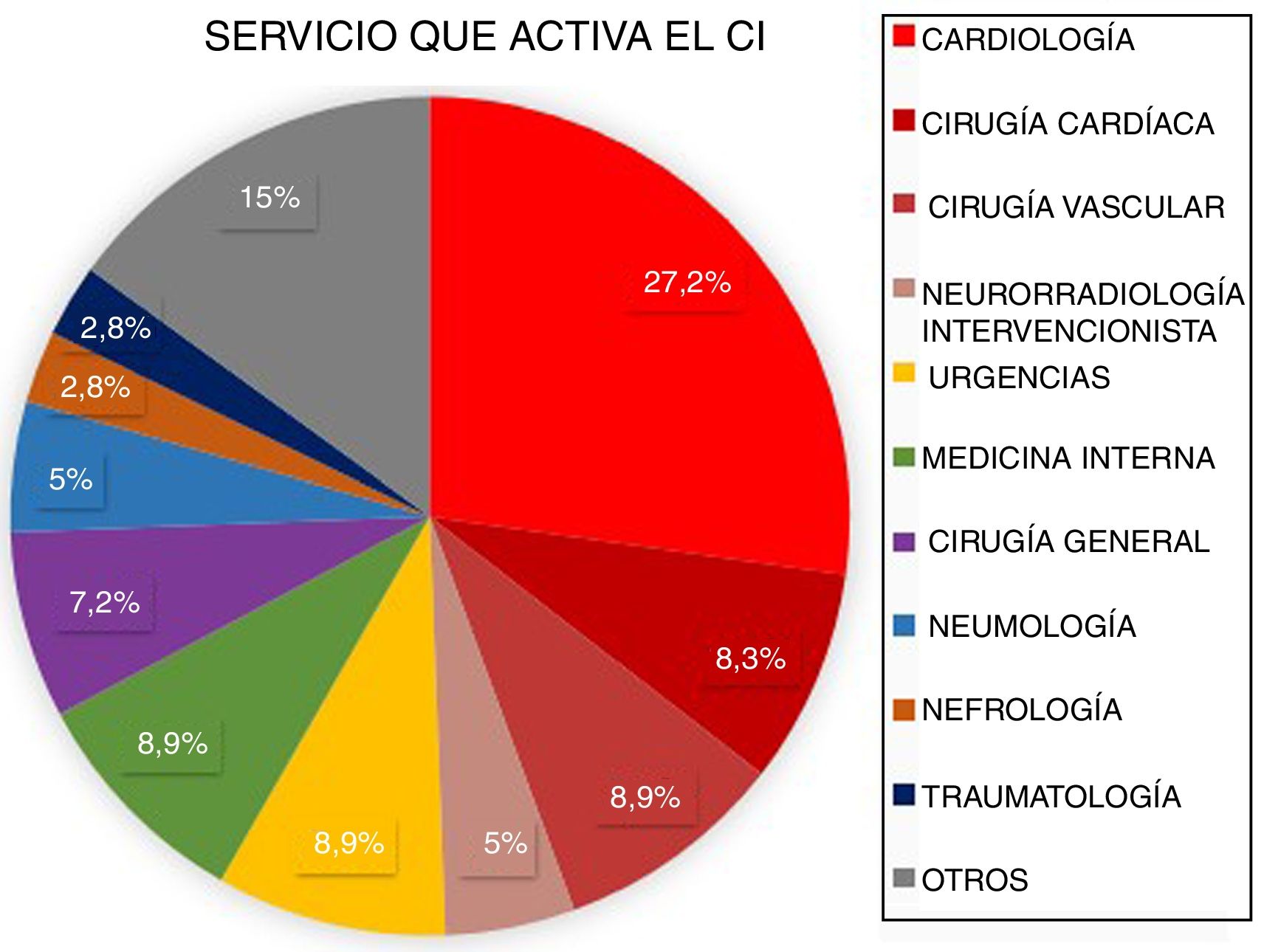

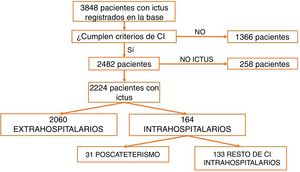

ResultsBetween March 2011 and April 2016, a total of 3848 patients were attended at our centre following code stroke activation. After excluding all patients not meeting diagnostic criteria for stroke (n=1366) and all cases of stroke mimics (n=258), a total of 2224 patients were finally included in the analysis. Of these, 2060 corresponded to pre-hospital code stroke activations and 164 (7.37%) to in-hospital code stroke activations (Fig. 1). Code stroke was most frequently activated by the cardiology and cardiac surgery departments (35.5%). Fig. 2 presents the percentages of code stroke activations by each department. A total of 31 patients presented post-catheterisation stroke, representing 18.9% of all in-hospital code stroke activations and 1.39% of all code stroke activations. Of these patients, 17 presented ischaemic stroke, 12 presented transient ischaemic attacks (TIA), and 2 presented haemorrhagic stroke.

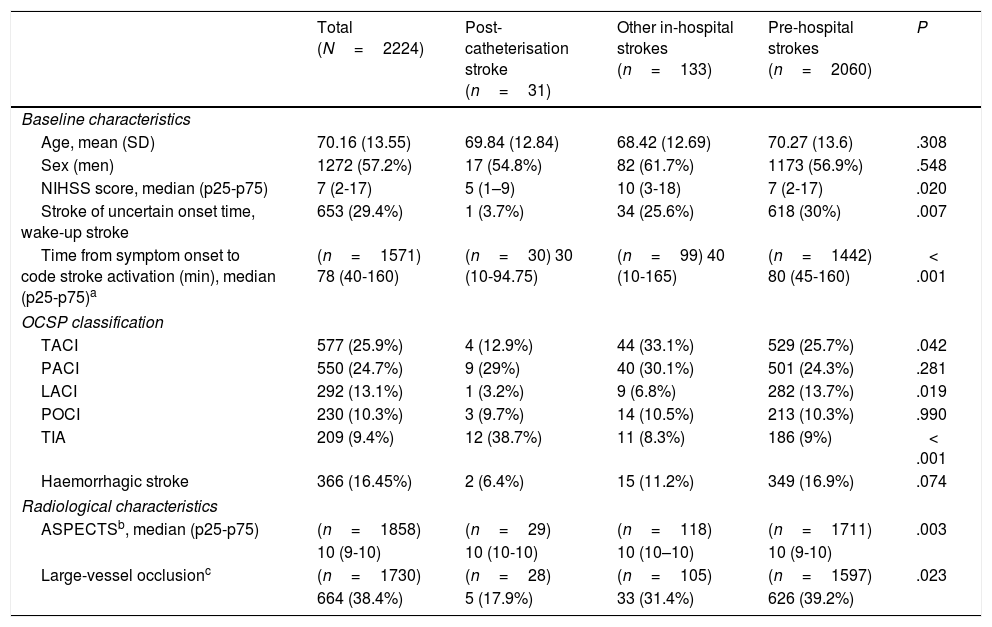

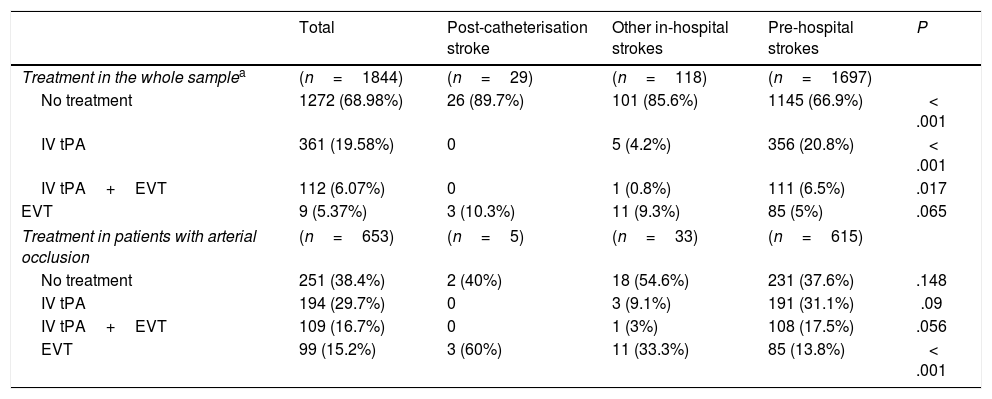

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics, diagnosis (OCSP classification), and radiological findings for the total sample and for each subgroup. The mean age of our sample was 70.16 years, and 57.2% of patients were men. Post-catheterisation stroke differed from the remaining in-hospital strokes and pre-hospital strokes in that it was initially less severe, was associated with faster code stroke activation, and had a different clinical presentation (less frequently presenting as total anterior circulation stroke or lacunar stroke, and more frequently as TIA) (Table 1). Likewise, large-vessel occlusions were less frequent in these patients than in the remaining in-hospital and pre-hospital strokes (17.9% vs 31.4% and 39.2%, respectively). Reperfusion treatment was less frequent among patients with post-catheterisation stroke or other types of in-hospital stroke than in cases of pre-hospital code stroke activation (10.3% and 14.4% vs 33.1%). However, in the case of large-vessel occlusion, endovascular treatment was significantly more frequent in patients with post-catheterisation stroke (Table 2).

Baseline clinical and radiological characteristics of our sample.

| Total (N=2224) | Post-catheterisation stroke (n=31) | Other in-hospital strokes (n=133) | Pre-hospital strokes (n=2060) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 70.16 (13.55) | 69.84 (12.84) | 68.42 (12.69) | 70.27 (13.6) | .308 |

| Sex (men) | 1272 (57.2%) | 17 (54.8%) | 82 (61.7%) | 1173 (56.9%) | .548 |

| NIHSS score, median (p25-p75) | 7 (2-17) | 5 (1–9) | 10 (3-18) | 7 (2-17) | .020 |

| Stroke of uncertain onset time, wake-up stroke | 653 (29.4%) | 1 (3.7%) | 34 (25.6%) | 618 (30%) | .007 |

| Time from symptom onset to code stroke activation (min), median (p25-p75)a | (n=1571) 78 (40-160) | (n=30) 30 (10-94.75) | (n=99) 40 (10-165) | (n=1442) 80 (45-160) | < .001 |

| OCSP classification | |||||

| TACI | 577 (25.9%) | 4 (12.9%) | 44 (33.1%) | 529 (25.7%) | .042 |

| PACI | 550 (24.7%) | 9 (29%) | 40 (30.1%) | 501 (24.3%) | .281 |

| LACI | 292 (13.1%) | 1 (3.2%) | 9 (6.8%) | 282 (13.7%) | .019 |

| POCI | 230 (10.3%) | 3 (9.7%) | 14 (10.5%) | 213 (10.3%) | .990 |

| TIA | 209 (9.4%) | 12 (38.7%) | 11 (8.3%) | 186 (9%) | < .001 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 366 (16.45%) | 2 (6.4%) | 15 (11.2%) | 349 (16.9%) | .074 |

| Radiological characteristics | |||||

| ASPECTSb, median (p25-p75) | (n=1858) | (n=29) | (n=118) | (n=1711) | .003 |

| 10 (9-10) | 10 (10-10) | 10 (10–10) | 10 (9-10) | ||

| Large-vessel occlusionc | (n=1730) | (n=28) | (n=105) | (n=1597) | .023 |

| 664 (38.4%) | 5 (17.9%) | 33 (31.4%) | 626 (39.2%) | ||

ASPECTS: Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score; LACI: lacunar infarction; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; OCSP: Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project; PACI: partial anterior circulation infarction; POCI: posterior circulation infarction; SD: standard deviation; TACI: total anterior circulation infarction; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

Reperfusion treatment administered in our sample.

| Total | Post-catheterisation stroke | Other in-hospital strokes | Pre-hospital strokes | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment in the whole samplea | (n=1844) | (n=29) | (n=118) | (n=1697) | |

| No treatment | 1272 (68.98%) | 26 (89.7%) | 101 (85.6%) | 1145 (66.9%) | < .001 |

| IV tPA | 361 (19.58%) | 0 | 5 (4.2%) | 356 (20.8%) | < .001 |

| IV tPA+EVT | 112 (6.07%) | 0 | 1 (0.8%) | 111 (6.5%) | .017 |

| EVT | 9 (5.37%) | 3 (10.3%) | 11 (9.3%) | 85 (5%) | .065 |

| Treatment in patients with arterial occlusion | (n=653) | (n=5) | (n=33) | (n=615) | |

| No treatment | 251 (38.4%) | 2 (40%) | 18 (54.6%) | 231 (37.6%) | .148 |

| IV tPA | 194 (29.7%) | 0 | 3 (9.1%) | 191 (31.1%) | .09 |

| IV tPA+EVT | 109 (16.7%) | 0 | 1 (3%) | 108 (17.5%) | .056 |

| EVT | 99 (15.2%) | 3 (60%) | 11 (33.3%) | 85 (13.8%) | < .001 |

EVT: endovascular treatment; IV tPA: intravenous fibrinolysis.

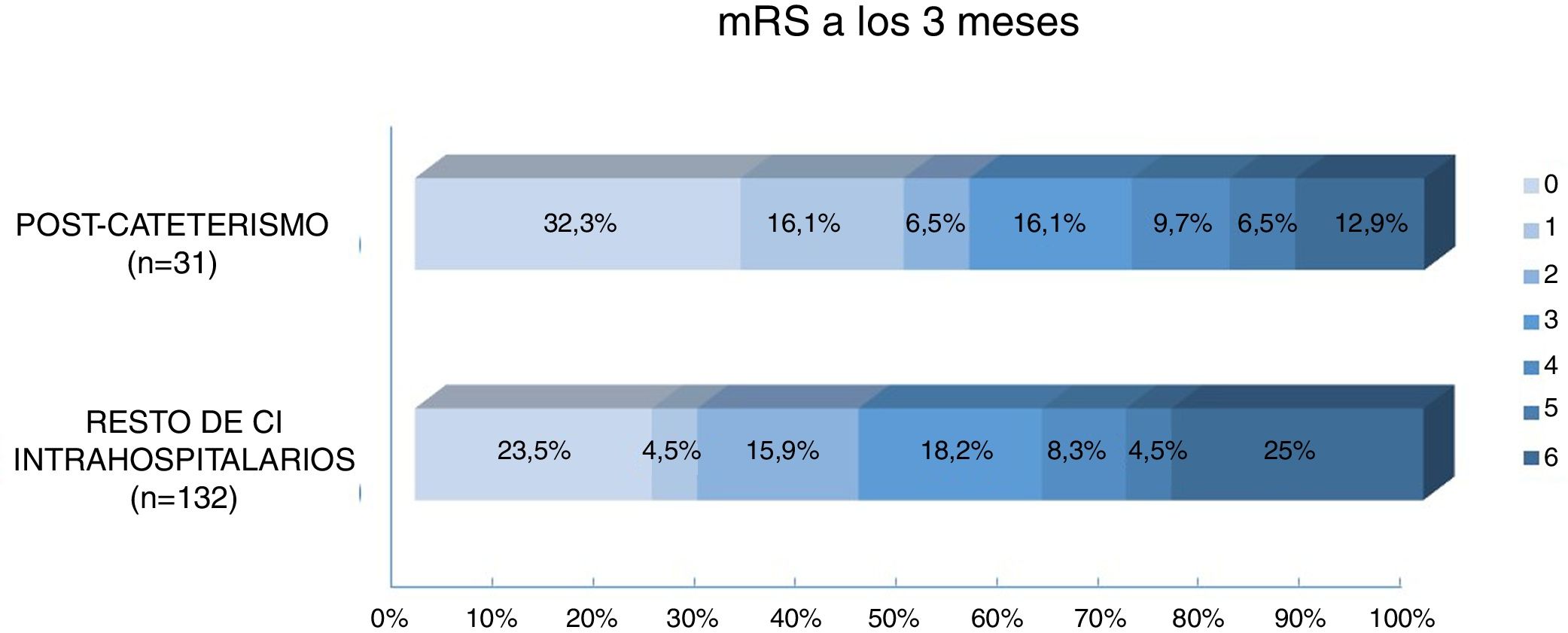

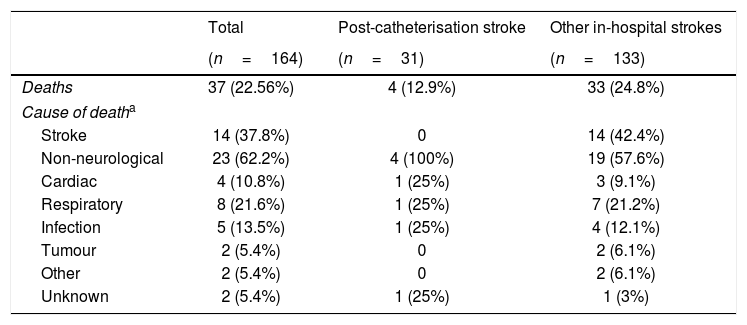

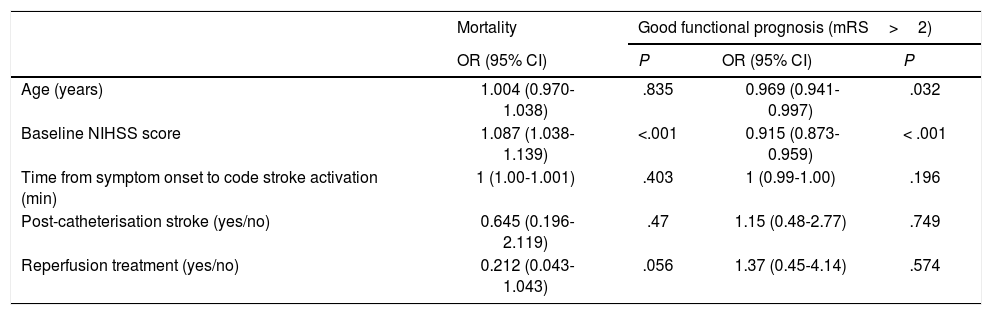

Regarding prognosis, patients with post-catheterisation stroke more frequently presented excellent functional prognosis than patients with other types of in-hospital stroke (48% vs 28%; P=.029), as well as a lower mortality rate (12.9% vs 25%, P=.14); no significant differences were observed in the percentage of good prognosis between groups (54.8% vs 44.7%; P=.31) (Fig. 3). In the group of other types of in-hospital stroke, 42.4% of deaths were due to stroke, whereas none of the patients with post-catheterisation stroke died as a result of the cerebrovascular event (Table 3). Post-catheterisation stroke was not independently associated with good clinical prognosis (P=.75) or mortality (P=.47); only baseline NIHSS score was found to be an independent predictor of mortality, while younger age was associated with good functional prognosis (Table 4).

Mortality in patients with post-catheterisation stroke and other types of in-hospital stroke.

| Total | Post-catheterisation stroke | Other in-hospital strokes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=164) | (n=31) | (n=133) | |

| Deaths | 37 (22.56%) | 4 (12.9%) | 33 (24.8%) |

| Cause of deatha | |||

| Stroke | 14 (37.8%) | 0 | 14 (42.4%) |

| Non-neurological | 23 (62.2%) | 4 (100%) | 19 (57.6%) |

| Cardiac | 4 (10.8%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| Respiratory | 8 (21.6%) | 1 (25%) | 7 (21.2%) |

| Infection | 5 (13.5%) | 1 (25%) | 4 (12.1%) |

| Tumour | 2 (5.4%) | 0 | 2 (6.1%) |

| Other | 2 (5.4%) | 0 | 2 (6.1%) |

| Unknown | 2 (5.4%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (3%) |

Multivariate analysis of mortality and good functional prognosis.

| Mortality | Good functional prognosis (mRS>2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (years) | 1.004 (0.970-1.038) | .835 | 0.969 (0.941-0.997) | .032 |

| Baseline NIHSS score | 1.087 (1.038-1.139) | <.001 | 0.915 (0.873-0.959) | < .001 |

| Time from symptom onset to code stroke activation (min) | 1 (1.00-1.001) | .403 | 1 (0.99-1.00) | .196 |

| Post-catheterisation stroke (yes/no) | 0.645 (0.196-2.119) | .47 | 1.15 (0.48-2.77) | .749 |

| Reperfusion treatment (yes/no) | 0.212 (0.043-1.043) | .056 | 1.37 (0.45-4.14) | .574 |

CI: confidence interval; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; OR: odds ratio.

According to our results, post-catheterisation stroke accounts for 1.4% of all code stroke activations and approximately 19% of all in-hospital code stroke activations. Our findings differ from those of a previous study conducted in our setting,13 which found that approximately 6% of all in-hospital strokes occurred either in the haemodynamic or the interventional neuroradiology units. This difference may be due to differences between hospitals in the number of coronarographies performed or the sensitivity of the cardiology team in identifying neurological symptoms of stroke.

Furthermore, only 6.4% of post-catheterisation strokes were haemorrhagic. While a previous study reported that haemorrhagic stroke accounted for 50% of strokes in these patients,14 that study included patients undergoing coronary artery revascularisation surgery with extracorporeal circulation, and therefore receiving heparin sodium, which may increase the risk of haemorrhagic stroke.

Code stroke was activated earlier in patients with post-catheterisation stroke than for other strokes, probably because these patients were under semi-intensive monitoring. Post-catheterisation stroke presented more frequently as a TIA and less frequently as lacunar infarct or total anterior circulation stroke, was initially less severe, and was less frequently associated with large-vessel occlusions. These differences may be explained by a higher frequency of emboligenic mechanisms in patients with post-catheterisation stroke, either due to detachment of atheromatous plaques from the aortic arch, thrombus formation in the catheter, or air embolism during contrast administration,15 which would cause occlusion of distal vessels, with spontaneous recanalisation in many cases. The lower severity of post-catheterisation strokes may explain why up to 90% of these patients received conservative treatment. Furthermore, the use of heparin sodium during coronarography probably led physicians to opt for endovascular treatment instead of systemic fibrinolysis in all cases. Some experts have designed management algorithms for these patients, and suggest the possibility of performing selective cerebral angiography in the haemodynamic unit if the medical team has experience with the procedure. Otherwise, the algorithm recommends following the standard diagnostic and treatment protocol after code stroke activation.15

Patients with post-catheterisation stroke presented a higher rate of excellent functional prognosis and lower mortality rates than patients with other types of in-hospital stroke. Better prognosis in this patient group was found to be linked to the lower severity of the episodes.

Although previous studies report high mortality rates (22%-37%) in patients with post-catheterisation stroke,2,14,16–18 mortality in our series was considerably lower (12.9%). Based on the period when patients were recruited and the lack of data on the treatment administered, we hypothesise that patients in previous studies did not receive specific treatment for stroke. In contrast, our patients were admitted to a stroke unit and treated according to the European stroke management guidelines, which may explain the great disparity in mortality rates. None of the patients with post-catheterisation stroke died due to the stroke, whereas in the group of patients with other types of in-hospital stroke, stroke explained 39.2% of patient deaths.

Our study presents several limitations. Firstly, while data were collected from a prospective registry, the study is subject to the limitations inherent to its retrospective design. Secondly, our results cannot be generalised due to the small size of the group of patients with post-catheterisation stroke and differences between hospitals in the availability of technologies and healthcare professionals specialising in stroke management.

In conclusion, post-catheterisation stroke is less severe than other types of in-hospital stroke, frequently presents as TIA, and is less commonly associated with large-vessel occlusion. Primary endovascular treatment is the reperfusion treatment of choice for cases of large-vessel occlusion. While stroke itself is a major factor in the mortality of patients with in-hospital strokes in general, it is rarely the cause of death in those with post-catheterisation stroke.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank all residents and consultant physicians at Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol for their effort in completing the registries. We are especially grateful to Anna Planas Ballvé, Joaquim Broto Fantova, Ane Miren Crespo Cuevas, Nicolau Guanyabens Buscà, Laura Abraira del Fresno, Tamara Canento Sánchez, Jordi Ciurans Molist, Daniela Samaniego Toro, Martí Paré Curell, Agustín Sorrentino Rodríguez, Nuolé Zhu, Sara Forcén Vega, Mireia Gea Rispal, and Marta Álvarez Larruy.

Please cite this article as: Martín-Aguilar L, Paré-Curell M, Dorado L, Pérez de la Ossa-Herrero N, Ramos-Pachón A, López-Cancio E, et al. Ischaemic stroke as a complication of cardiac catheterisation. Ictus isquémico como complicación del cateterismo cardíaco. Características clínicas, radiológicas y evolutivas e implicaciones terapéuticas. Neurología. 2022;37:184–191.

This study was presented in poster format at the 68th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology, held in November 2016.