Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas (DAVF) are abnormal arteriovenous shunts connecting a feeding dural artery and a draining dural vein. They account for 10% to 15% of all intracranial vascular malformations.1 Structural causes of reversible parkinsonism are extremely rare; however, they have been described in association with deep cerebral vein thrombosis and DAVFs.2,3 We present the case of a patient with a reversible gait disorder secondary to venous stroke caused by a type III DAVF (Cognard classification).4

Our patient was a 77-year-old man with no relevant medical history. He was transferred to our hospital in 2008 due to atypical gait disorder and a 4-year history of focal pyramidal symptoms. Other centres had already diagnosed him with Parkinson's disease (although a subsequent l-DOPA test yielded negative results) and motor neuron disease. The initial neurological examination revealed right leg motor deficit (4/5 distally) and right leg pyramidal syndrome with mild spasticity (Modified Ashworth Scale grade 1), right-sided exaggerated patellar reflexes (++++), and Babinski sign. The patient's salient feature was a gait disorder not fully ascribable to the pyramidal syndrome. It was characterised by small steps and difficulty initiating gait, which is more suggestive of an extrapyramidal disorder. He also presented generalised bradykinesia and micrography. An MRI scan showed a malacic lesion in the left prerolandic region. Although rehabilitation was started during outpatient monitoring, the gait disorder worsened progressively; however, the patient experienced no falls. Twelve months later, he presented secondary epilepsy manifesting as simple partial seizures with secondary generalisation and producing motor symptoms in the right lower limb. Seizure frequency was 1 to 2 seizures per month and it did not decrease despite treatment with valproic acid and lamotrigine. The patient attended the emergency department at our hospital in 2009 due to a new simple partial seizure in the right leg with secondary generalisation, worsened gait, and memory problems, slow thinking, and emotional lability presenting subacutely (seemingly chronologically unrelated to antiepileptic treatment). He was admitted to undergo a complete study that would allow us to optimise treatment.

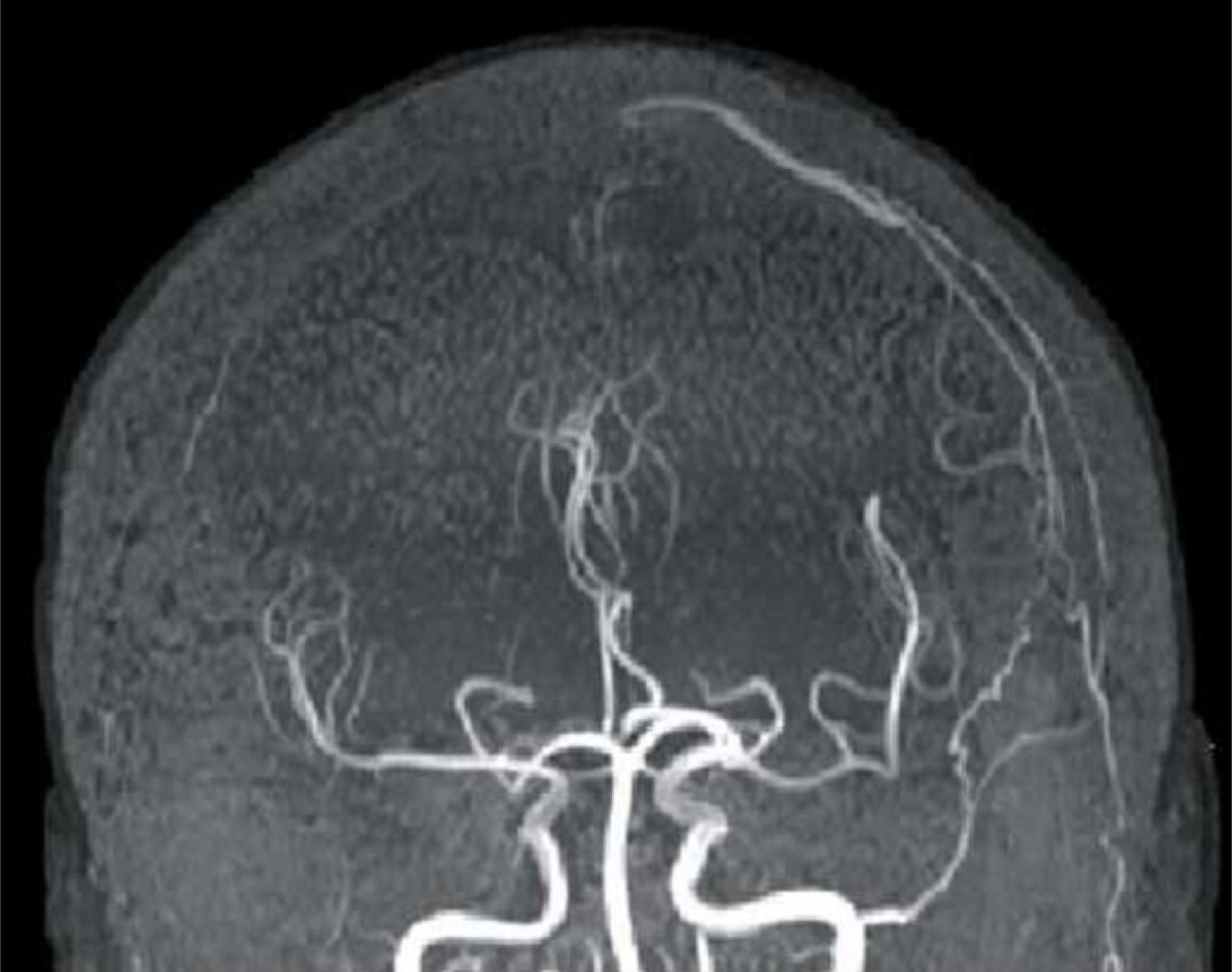

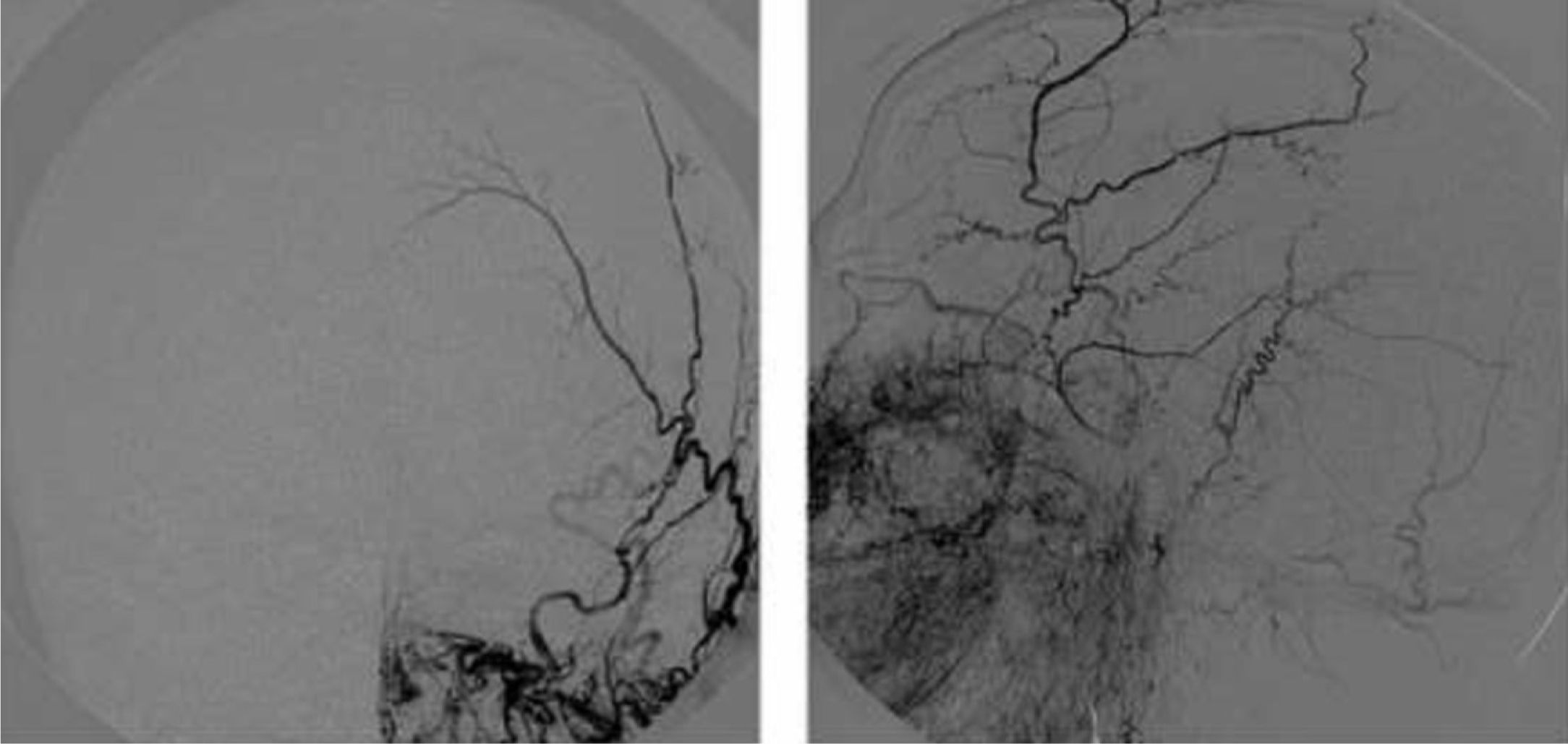

FLAIR and T2-weighted sequences in the initial cranial MRI scan revealed hyperintensities consistent with venous stroke in parasagittal precentral subcortical white matter. MR angiography revealed artery permeability and a superficial cortical vein with early filling at the left frontal level, arterialisation of that vein, and hypertrophy of a branch of the ipsilateral external carotid artery linked to that structure (Fig. 1). Conventional arteriography showed a mixed pial-dural fistula; dural supply came from the anterior and posterior branches of the left middle meningeal artery. The latter drained into the cortical vein towards the superior longitudinal sinus (type III DAVF). The pial component was supplied by branches of the left middle cerebral artery (Fig. 2). The posterior branch of the middle meningeal artery, which fed the fistula, was selectively catheterised. The patient underwent embolisation and complete exclusion of the fistula with no complications. Multiple serial EEGs showed no epileptiform activity but they did reveal bursts of diffuse slow delta activity, predominantly in the left hemisphere.

The patient has experienced significant improvements in gait and motor function, with no further epileptic seizures to date. A follow-up MRI scan showed that the fistula had closed.

The literature describes several cases of parkinsonism in patients with DAVFs.5,6 Dural venous sinus thrombosis has been suggested to be the precipitating factor for DAVFs7,8; lesions would result from increased venous pressure in the dural venous sinus. Both DAVF symptoms and prognoses are highly variable.9 Some of the most frequently described clinical manifestations are focal epilepsy, headache with or without symptoms of intracranial hypertension, facial pain, and intracranial or subarachnoid haemorrhage. Conventional arteriography is the gold standard diagnostic imaging study. Management of DAVFs may require a multidisciplinary approach including embolisation and surgery or radiosurgery.10

In conclusion, DAVFs are a potentially treatable cause of rapidly progressive gait disorders. Early diagnosis of this vascular anomaly requires a high level of clinical suspicion.

Please cite this article as: Navalpotro-Gomez I, Rodríguez-Campello A, Vivanco-Hidalgo RM, Vivas E, Roquer-Gonzalez J. Trastorno progresivo de la marcha y epilepsia secundarios a infarto venoso por fístula dural arteriovenosa tipo III. Neurología. 2015;30:450–451.

This original article has not been presented at the SEN's Annual Meeting.