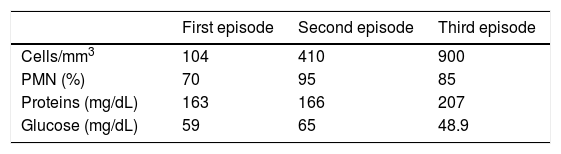

Drug-induced meningitis is an infrequent entity but should be considered in recurrent or unexplained episodes of meningitis. It has mainly been described in association with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, intravenous immunoglobulins, immunosuppressants, vaccines, and intrathecal agents.1 The literature includes 3 exceptional reports of cases related to allopurinol.2–4 We describe a new case of recurrent meningoencephalitis probably caused by allopurinol. Our patient was a female smoker aged 74 years, with a history of hypertension and hyperuricaemia, who was being treated with allopurinol, olmesartan/hydrochlorothiazide, and omeprazole. She was admitted to our hospital due to a third episode of language impairment and confusion. In the first episode, 2 months before, the patient was admitted to another hospital due to symptoms of disorientation and aphasia upon awakening. The patient experienced general discomfort with asthenia and headache in the days leading up to the episode. No fever was reported. A cranial CT scan yielded normal results, whereas lumbar puncture (LP) revealed pleocytosis of 104 cells (70% PMN), high protein levels (163mg/dL), and a glucose level of 59mg/dL. Microbiology tests (conventional culture and PCR study for HSV in the CSF; serology tests for cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr, varicella-zoster, Borrelia burgdorferi, HIV, and syphilis) yielded negative results. The patient received treatment for 14 days with acyclovir at 10mg/kg/8h, with symptoms resolving on the fifth day after admission. Brain MRI results were normal. Two months later, the patient was admitted a second time, with similar symptoms, but again with no fever. A new LP revealed 410 cells (95% PMN), with high protein levels (166mg/dL) and a glucose level of 65mg/dL. The same microbiology tests were performed as in the previous episode, in addition to a PCR for mycobacteria; all tests returned negative results. A new CT scan showed no abnormalities. The patient was treated with intravenous ceftriaxone dosed at 2mg/24h for 10 days, and symptoms fully resolved at 48-72h of admission. The night of her discharge, she started experiencing headache and nausea, and again displayed confusion and language impairment the following morning. The patient was transferred to our hospital at this time. At arrival, she presented bradypsychia, disorientation, and severe mixed aphasia, with no signs of long pathway involvement, meningitis, or fever. A new LP revealed 900 cells (85% PMN), with high protein levels (207mg/dL), and a glucose level of 48.9mg/dL. Gram stain was negative and adenosine deaminase (ADA) level was <4IU/L. Therefore, this was a third episode of headache, aphasia, and confusion, with increasing PMN pleocytosis in the CSF and high CSF protein levels, with full clinical resolution between episodes. We performed a new cranial MRI scan, as well as microbiology tests, antineuronal antibodies, a whole-body CT scan, and autoimmune profiling; all yielded normal results. We started treatment with cefotaxime (2g/4h), ampicillin (2g/4h), vancomycin (1g/12h), and tuberculostatic drugs (isoniazid, 250mg/24h, pyrazinamide, 1500mg/24h, rifampicin, 600mg/24h, and ethambutol, 1000mg/24h). Symptoms resolved 3 days after admission. Due to the low level of clinical suspicion, tuberculostatic drugs were suspended; the triple antimicrobial therapy was continued for 14 days. Once infectious aetiology of the symptoms could reasonably be ruled out, we considered the possibility of drug-induced aseptic meningoencephalitis. Considering the absence of CSF lymphocytosis, we ruled out a diagnosis of HaNDL syndrome. The patient was receiving several drugs, including allopurinol. We became aware that the patient had started treatment with allopurinol 2 months before her first admission. During her first stay in hospital, she did not receive allopurinol; this coincided with the improvement she experienced a few days later. Two months later, in her home, she resumed treatment and experienced symptom relapse just 2 days later. Again, during the second admission, treatment with allopurinol was unintentionally suspended, and her clinical symptoms again improved rapidly within a few days. We could not confirm whether the patient took allopurinol in her home the day of discharge; she was admitted the following day due to a third episode. Considering the chronology of the episodes of meningoencephalitis and their temporal association with the administration of allopurinol, we recommended replacing the drug with an alternative urate-lowering drug, febuxostat. After one year and 3 months of follow-up, the patient has remained asymptomatic and has suffered no further episodes.

The causes of recurrent aseptic meningitis include chronic inflammatory diseases, structural lesions (craniopharyngioma and epidermoid cyst), chronic infections (syphilis, Lyme disease, HIV, HSV, etc.), and consumption of some drugs, in addition to Mollaret meningitis.1 Drug-induced aseptic meningitis is a diagnostic challenge and is frequently mistaken for infectious processes.5 CSF analysis usually shows marked pleocytosis, with hundreds or thousands of cells per cubic millimetre, normal or low glucose levels, and increased protein levels. Brain MRI usually shows normal results or non-specific findings. The interval between administration of the drug and the onset of meningitis may range from minutes to 4 months. When a patient is administered the drug again, symptoms typically reappear within the first 12h; pleocytosis tends to be more pronounced with successive episodes (Table 1). Pathogenesis of the syndrome is yet to be fully understood.5 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, some antibiotics, intravenous immunoglobulins, and some immunosuppressants are the drugs most frequently identified as potential causes of aseptic meningitis; however, we should also be aware of other, less frequent causes, such as allopurinol.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Pereda S, Lage-Martínez C, Paredes MJ, Infante J. Meningoencefalitis recurrente por alopurinol. Neurología. 2018;33:557–558.