Myeloid or granulocytic sarcoma is a rare tumour composed of immature myeloid precursor cells which develop outside the bone marrow, affecting any organ. It may manifest before, during, or after the diagnosis of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) or other myeloproliferative disease.1–4 Only 2%-8% of patients with AML develop a myeloid sarcoma; manifestation before leukaemia diagnosis is rare.4,5

The World Health Organization classifies AML according to cell predominance and degree of maturity. Extramedullary disease is associated with some of the cytological variants included in the French–American–British classification; association with acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) is extremely rare.1,2

APL is characterised by an abnormal proliferation of promyelocytes and is classified as M3 under the French–American–British classification. APL is caused by a translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 15 and 17; fusion between the RARA and PML genes is of therapeutic significance.6,7

Only 10% of cases of AML correspond to APL, which is characterised by a favourable prognosis. The skin and the central nervous system (CNS) are the most frequent sites of extramedullary involvement in APL; chloroma, more appropriately termed promyelocytic sarcoma in this context, is an uncommon manifestation.1,8 Promyelocytic sarcoma is extremely rare, and usually manifests as a relapse of APL.4

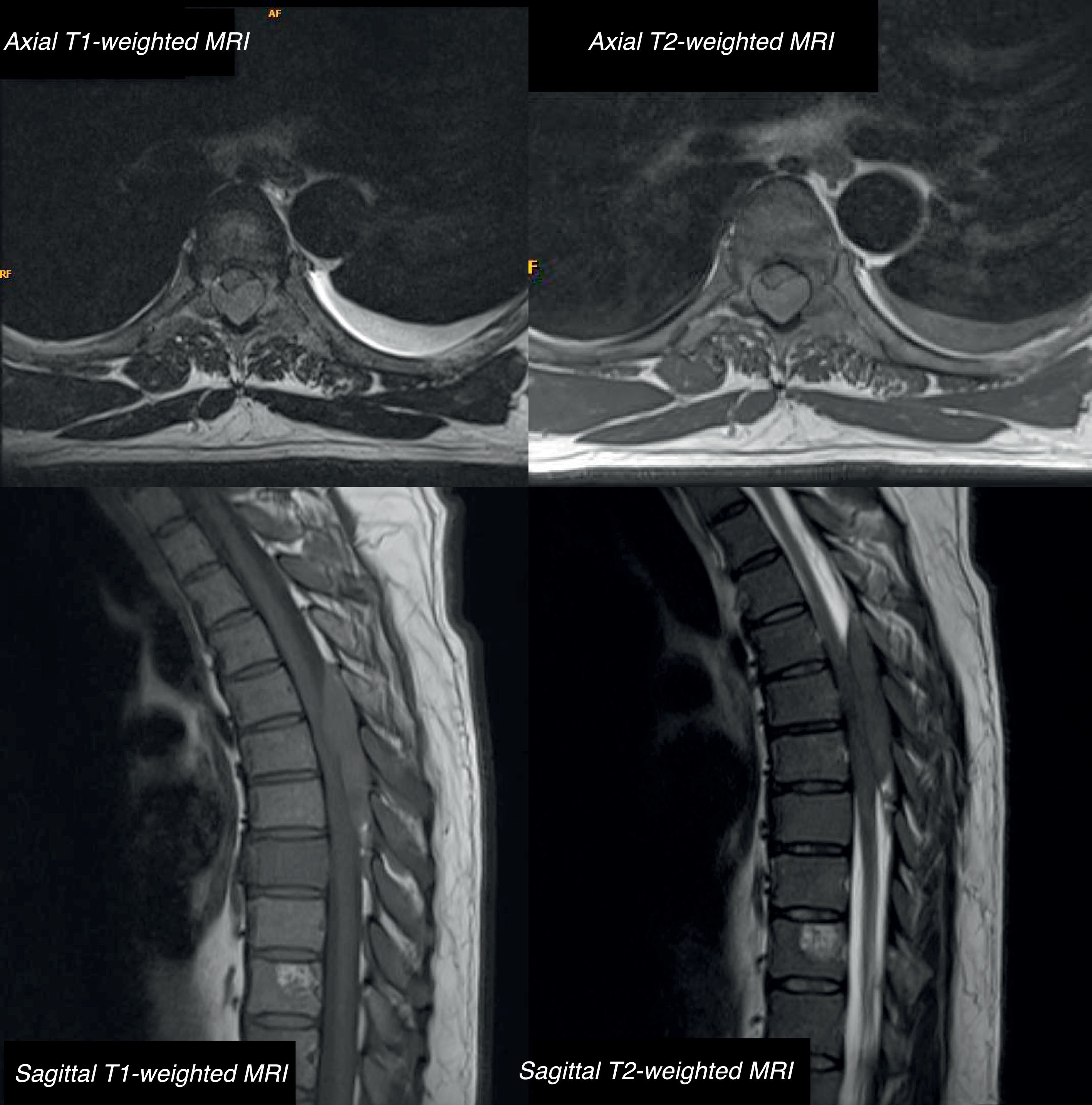

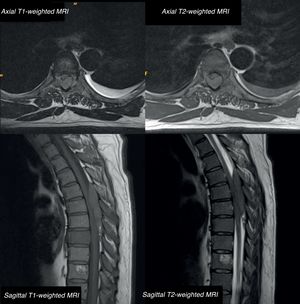

We present the case of a 42-year-old male patient with a 2-month history of bone pain, pleural effusion, and low-grade fever. In a period of less than 24h, he developed haematuria, severe paraparesis preventing him from walking, decreased sensitivity in the lower limbs, and acute urinary retention. The examination revealed overall strength of 2/5 in the lower limbs, absence of deep tendon reflexes, and bilaterally absent plantar reflex. He presented loss of proprioceptive sensitivity and tactile hypoaesthesia at the T4 level, loss of sphincter tone, and absent cremasteric reflex; all these findings are compatible with incomplete spinal cord lesion. A lumbar MRI (Fig. 1) showed an epidural mass from T5 to T8, causing spinal cord compression and multiple bone lesions. The complete blood count and biochemical and coagulation studies obtained normal results. We performed an emergency decompressive laminectomy with complete resection of the epidural tumour. Forty-two hours after the surgery, the patient developed thrombocytopaenia with precursor cells and promyelocytes in the peripheral blood. Bone marrow biopsy revealed hypercellularity, with infiltration of atypical promyelocytes. By means of flow cytometry/FISH analysis, we diagnosed a spinal promyelocytic sarcoma as a manifestation of acute promyelocytic leukaemia with M3 morphology according to the French–American–British classification with t(15;17)(q22;q21) and PML-RARA fusion gene. The patient was treated according to the Spanish Programme for Haematological Treatment (Programa Español de Tratamiento en Hematología [PETHEMA], protocol code LPA-AR/2011): induction chemotherapy (idarubicin+all-trans retinoic acid [ATRA]) and consolidation chemotherapy (idarubicin+cytarabin, cytosine arabinoside+ATRA). We administered complementary radiotherapy at the thoracic level and 2 doses of triple intrathecal chemotherapy (methotrexate+hydrocortisone+cytarabine) during induction and consolidation therapies. Neurological outcomes were satisfactory, with progressive recovery until he was able to walk with orthoses; lower limb strength was 4/5 in the hips, 5/5 in the knees and 4/5 in the ankles, with exaggerated deep tendon reflexes bilaterally. We observed tactile hypoaesthesia and hypoalgesia below the T10 level, predominating on the right side; sphincter function was recovered. No signs of disease in the CSF or paraspinal masses were observed. Bone marrow biopsy ruled out a relapse, confirming complete remission with negative results for PML/RARA.

Thoracic MRI: axial and sagittal T1-weighted sequence without contrast and T2-weighted sequence. A posterior isointense epidural mass extends from T5 to T8, compressing the posterior section of the spinal cord. The scan also reveals multiple bone lesions in the thoracolumbar spine, involving both the posterior elements and the vertebral bodies of all dorsal vertebrae and L1.

APL is a subtype of AML that usually manifests with pancytopaenia and severe coagulation disorders. It represents 10%-15% of all cases of AML and is most frequent in Latin America, Spain, and Italy. APL is the most curable of all forms of AML, mainly due to treatment with ATRA in association with chemotherapy agents.6,8,9

The terms granulocytic sarcoma, myeloid sarcoma, and chloroma define the rare malignant neoplasms resulting from the extramedullary proliferation of mature or immature myeloblasts in association with AML, myelodysplastic syndromes with leukaemic transformation, chronic myeloid leukaemia with blastic crisis, or absence of leukaemia.3

Extramedullary infiltration is a very rare complication of AML generally, but it is extremely rare in APL. Most of the cases reported are related to a relapse after treatment, with central nervous system and cutaneous involvement being the most frequent. Factors associated with extramedullary recurrence are age <45 years, high white cell count, bcr3 isoform of the PML/RARA fusion gene, and treatment with ATRA. Manifestation with extramedullary disease and no signs of leukaemia is extraordinary.5,6,9

Treatment with ATRA in patients with AML favours the appearance of granulocytic sarcoma, due to the increased expression of adhesion molecules in leukaemic promyelocytes and their ligands in endothelial cells. It is also believed to facilitate the passage of malignant promyelocites across the blood–brain barrier and to predispose patients to relapse in unusual locations.6

Granulocytic sarcoma is easily diagnosed when it synchronously manifests with AML or as a relapse of a treated AML. However, diagnosis is more complicated when it manifests before onset of AML. More than 75% of these sarcomas are misdiagnosed as other types of neoplasms, mainly malignant lymphomas. Some of the recommended diagnostic techniques include electron microscopy, systematic staining indicating myeloid differentiation combined with panels including naphthol-ASD chloroacetate, myeloperoxidase, immunoperoxidase stain for lysozyme, and CD34 together with other B- and T-lineage markers, in particular CD79a and CD3.2,3,5,6,10

Patients with aleukaemic granulocytic sarcoma will eventually develop acute leukaemia. Between 66% and 88% of these patients are estimated to experience acute myeloid leukaemia 9-11 months after diagnosis.3

Treatment of granulocytic sarcoma in the absence of leukaemia should include high doses of specific chemotherapy agents for treating AML, with or without radiotherapy.3,5 When left untreated, most primary granulocytic sarcomas will progress to leukaemia. Treatment consisting of local procedures, including tumour resection and radiotherapy with no chemotherapy, involve higher risk of systemic disease.5

Standard treatment consists of the combination of ATRA with chemotherapy with anthracyclines. Total remission rates amount to 85%-95%, with a 5-year survival rate of 65%-70% in both children and adults.5 The Spanish PETHEMA programme has shown significantly higher remission rates than other groups, with a lower number of deaths during induction and consolidation therapies. Furthermore, disease-free survival after complete remission is comparable with and even surpasses that obtained with other established protocols.11

Thousands of cases of granulocytic sarcomas have been reported in association with different AML subtypes, but there are only 8 reported cases of granulocytic sarcomas with APL, of which 3 were in non-leukaemic patients.2

In conclusion, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential for obtaining satisfactory results.

Please cite this article as: Villaseñor-Ledezma J, Amosa-Delgado M, Ruíz-Ginés JA, Álvarez-Salgado JA. Sarcoma promielocítico espinal como manifestación previa a una leucemia aguda promielocítica. Neurología. 2018;33:558–560.