Intracranial subdural haematoma (SH) rarely presents as a complication of epidural anaesthesia, although we do find cases in the literature. If the dura mater is punctured during this procedure, there is a risk that SH will occur, and that risk may be related to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hypotension syndrome.

Symptoms of SH are linked to the mass effect and displacement of structures, and they depend on the patient's age; haematoma location, size, and speed of onset; the patient's prior clinical condition; and the compression of intracranial structures. Distinguishing CSF hypotension syndrome from SH due to intracranial hypertension may be difficult in differential diagnosis, and this can be an obstacle to diagnosing the condition early.

We present the case of a patient with no relevant personal history who presented a SH secondary to the epidural anaesthesia received during childbirth.

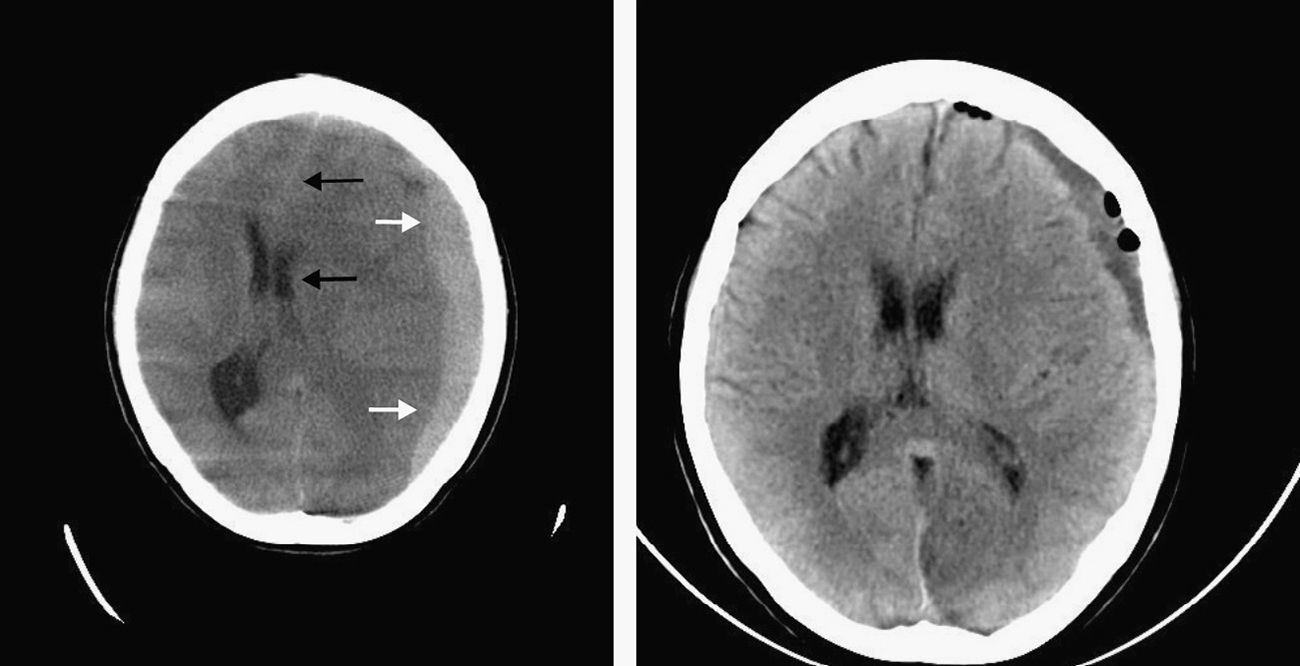

A 27-year-old woman came to our hospital's emergency department on 2 consecutive occasions due to a frontal and occipital headache that increased while standing and improved upon lying down. These visits took place 4 days after a normal vaginal delivery without complications. Epidural anaesthesia had been administered during childbirth by means of an 18 gauge Weiss needle used to inject levobupivacaine into the L2–L3 intervertebral disc space. Blood pressure (BP) was 148/73mmHg and heart rate (HR) was 70bpm. Physical examination did not reveal any pathological signs, marfanoid/leptosomatic habitus, or articular hypermobility/skin hyperlaxity. Neurological examination showed no focal signs. The patient was discharged with analgesic and anti-inflammatory treatment. In the following weeks, she experienced a postural headache that did not prevent her from performing her daily activities and that resolved or lessened with the analgesic treatment prescribed. Approximately one month later, she returned to our department due to an intense headache which did not respond to postural change or improve with habitual analgesics. It was accompanied by vomiting and a state of anxiety and agitation. BP was 136/86mmHg and HR was 37bpm. Neurological examination revealed no pathological findings. The blood count, biochemical and coagulation study, venous blood gas values, and urine analyses provided no significant findings. The ECG detected sinus bradycardia with no other findings. The chest radiography was normal. The brain CT showed an extensive subacute left fronto-temporo-parietal SH with significant mass effect shifting the midline and ventricular system 14mm to the right (Fig. 1). After the case was discussed with the neurology department at the referral hospital, the patient was transferred to that centre. While in the emergency room prior to being transferred, she experienced an abrupt decrease in level of consciousness (GCS score of 3) and anisocoria. Doctors therefore decided to administer sedatives, relaxants, and anti-oedema drugs, as well as orotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Upon her arrival at the referral hospital, doctors performed emergency evacuation of the haematoma using 2 burr holes (one in the parietal and frontal lobe and the other in the left parietal and posterior lobe). Fluid exited under considerable pressure. The patient made good clinical progress; fluid output was abundant and her level of consciousness increased (GCS 15). Brain CT was then performed, revealing re-expansion of the cerebral parenchyma and resolution of the midline shift (Fig. 1). The patient was subsequently discharged and monitored by her primary care doctor and local neurologist; she will also require check-ups in the neurosurgery outpatient unit.

SH is defined as a collection of blood in the cranial cavity between the dura and arachnoid mater. Its most common aetiology is trauma. Chronic SH was first described by Wepfer (1658) and Morgani (1761). In 1857, Virchow wrote that the aetiology of what he called ‘pachymeningitis hemorrhagica interna’ was not traumatic.1,2 In 1914, Trotter1–3 considered the possibility of SH being caused by the rupture of small veins in the arachnoid mater. SH as a result of epidural anaesthesia is rare, with a prevalence ranging from 1/500000 to 1/1000000.4

Post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is the most frequent complication of epidural anaesthesia. It is associated with CSF hypotension syndrome, since CSF extravasation by lumbar puncture decreases the intracranial pressure. According to the International Headache Society's diagnostic criteria (2004, ICHD-II),5,6 the characteristic feature of PDPH is postural headache that appears or intensifies after 15minutes of standing and improves upon lying down for a similar time period. Studies show that symptoms last no more than 5 days in most cases.5 When CSF pressure decreases suddenly, the displacement of brain structures may cause intracranial subdural veins to tear, giving rise to SH.7–10 Many authors have linked the appearance of SH to the technique and material used in lumbar puncture, stating that larger needle diameter, pencil-point type needle tips, and the angle of the bevel are associated with a higher probability of vascular lesion.1 However, the solution to the problem does not seem to reside in the type of needle, since there are also documented cases of SH secondary to epidural anaesthesia with fine gauge needles.1–5

We should highlight that during the acute phase of SH, intracranial pressure (ICP) increases due to the larger brain volume. In advanced stages, this phenomenon leads to hypoperfusion and ischaemia of the brainstem, which increases the activity of the sympathetic and parasympathetic autonomous nervous system in an attempt to increase the stroke volume and the BP to a level exceeding the pressure on the brainstem. The purpose of this process is to overcome the vascular resistance to cerebral blood flow caused by increased ICP.11–15 This physiological response to elevated ICP is called the Cushing reflex and it is described clinically by the triad of arterial hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular breathing, indicators of poor clinical prognosis. In the case we describe, doctors detected bradycardia, but no arterial hypertension or irregular breathing.

Headaches that last more than one week after lumbar administration of epidural anaesthesia, stop responding to postural change, or appear with focal neurological signs should alert us to the possibility of an acute intracranial process. Symptoms of such processes no longer reflect CSF hypotension – the typical feature of PDPH – but rather intracranial hypertension, mass effect, and displacement of intracranial structures caused by SH.

Please cite this article as: López Soler EC, et al. Hematoma subdural secundario a anestesia epidural. Una complicación infrecuente. Neurología. 2013;28:380–2.