The role of statins after ischaemic stroke changed with the publication of the SPARCL study in 2006. We analyse how this has influenced the prescription of statins in this patient population.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective study of patients discharged with ischaemic stroke at the Virgen Macarena, Virgen del Rocío, and Valme hospitals in Seville (Spain) over two periods: 1999-2001 and 2014-2016.

ResultsThe study included 1575 patients: 661 (42%) were women and mean age (standard deviation) was 69 (10) years. Patients from the later period are older (68 [10] vs 71 [11]; P = .0001); include a higher proportion of women; and present higher rates of dyslipidaemia, hypertension, and diabetes. At discharge, statins were used in 18.7% of patients (vs 86.9% in the first period; P = .0001), with high-intensity statins prescribed in 11.1% of cases (vs 54.4%; P = .0001). In both periods, atorvastatin was the most commonly prescribed statin (80 mg: 6% vs 42.7%; 40 mg: 5.1% vs 11.1%). In the first period, the use of statins and high-intensity statins was correlated with hypercholesterolaemia, and inversely correlated with age. In the second period, statin use was correlated with hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia, and high-intensity statin use was correlated with ischaemic heart disease and inversely correlated with age.

ConclusionThere has been a clear change in the prescription of statins to patients with ischaemic stroke at discharge. However, many patients remain undertreated and the use of these drugs needs to be optimised.

El papel de las estatinas tras el ictus isquémico cambió con la publicación del estudio SPARCL en 2006. Nos planteamos valorar cómo ha influido en la prescripción de estatinas en esta población.

MétodoEstudio retrospectivo de las altas por ictus isquémico en los hospitales Virgen Macarena, Virgen del Rocío y Valme de Sevilla durante dos periodos: 1999-2001 y 2014-2016.

ResultadoIncluimos 1.575 pacientes, 661 (42%) mujeres, edad media 69 (± 10) años. Comparando los dos períodos, los pacientes del grupo post-SPARCL tienen mayor edad (68 ± 10 vs. 71 ± 11, p = 0,0001), mayor proporción de mujeres y mayor frecuencia de dislipidemia, hipertensión y diabetes. Al alta se utilizaron estatinas en el 18,7% frente al 86,9% (p = 0,0001), y estatinas de alta intensidad en el 11,1% frente al 54,4% (p = 0,0001), respectivamente. En ambos períodos la atorvastatina fue la estatina más recetada (80 mg, 6% vs. 42,7%; 40 mg, 5,1% vs. 11,1%). En el primer grupo, el uso de estatinas y de estatinas de alta intensidad se correlacionó con la hipercolesterolemia, y de forma inversa con la edad. En el segundo grupo, el uso de estatinas se correlacionó con la hipertensión y la hipercolesterolemia, y el de estatinas de alta intensidad, con la cardiopatía isquémica y, de forma inversa, con la edad.

ConclusiónExiste un cambio evidente en la prescripción de estatinas al alta en pacientes con ictus isquémico. No obstante, muchos pacientes siguen infratratados y es preciso optimizar su uso.

Statins, a group of drugs that inhibit the enzyme 5-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, are regarded as the most important advance in stroke prevention since the introduction of aspirin and antihypertensive drugs.1 In fact, a meta-analysis of trials of statins, including a total of 165 792 individuals, revealed that each 1 mmol/L (39 mg/dL) decrease in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is equivalent to a 21.1% reduction in the relative risk of stroke (95% CI: 6.3-33.5; P = .009).2

The unexpected finding of a decrease in the incidence of stroke in 2 intervention studies of statins for established coronary heart disease paved the way for the use of statins for stroke prevention.3,4 Since then, numerous studies have expanded the applications of these drugs in cerebrovascular disease.5

However, the SPARCL trial,6 published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2006, was crucial for vascular neurology in general and for the use of statins in stroke in particular. This was the first study to demonstrate that high-dose statins (80 mg atorvastatin) significantly reduced the risk of stroke in individuals with recent history of cerebrovascular disease and no coronary heart disease.

These findings were reflected in subsequent clinical practice guidelines for the prevention of ischaemic stroke. In fact, the 2008 update of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guidelines already recommends the use of high-intensity statin therapy in patients with atherosclerotic ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) (class I, level of evidence B), based on the results of the SPARCL trial7; these results changed neurological clinical practice, with statins being incorporated to the standard treatment of patients with ischaemic stroke.

Statin therapy is now a key component in the secondary prevention of ischaemic stroke. However, few studies have analysed prescription trends, the factors involved in statin prescription, or the doses used in patients with ischaemic stroke.

This study examines the changes in statin prescription patterns in patients with recent history of ischaemic stroke, gathering real clinical practice data from a representative sample of discharged patients, and explores the factors associated with the use of statins and high-intensity statin therapy.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective observational study of patients diagnosed with ischaemic stroke and discharged from the Virgen Macarena, Virgen del Rocío, and Virgen de Valme university hospitals, in Seville (Spain).

Patients were gathered from 2 different periods: before the publication of the SPARCL trial (pre-SPARCL group: 1999-2001) and a decade after its publication (post-SPARCL group: 2014-2016); we randomly selected a representative sample of consecutive patients from each period.

The inclusion criterion was diagnosis of ischaemic stroke at discharge. Stroke was defined as presence of sudden-onset focal neurological deficits persisting for over 24 hours with radiological evidence of the event (CT or MRI).

No exclusion criteria were established.

We gathered demographic and clinical data, as well as the type of statin and the dose prescribed at discharge.

The definition of high-intensity statin therapy was based on the criteria proposed in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association clinical practice guidelines, which defines high-intensity statin therapy as statin treatment achieving a decrease of over 50% in LDL-C levels, and includes rosuvastatin dosed at 20 and 40 mg daily and atorvastatin dosed at 40 and 80 mg daily.8

Statistical analysisData were analysed using the SPSS statistical software, version 22.0. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables were expressed as percentages.

We subsequently studied the association between patient clinical characteristics and the use of statins and high-intensity statin therapy. Continuous variables were compared using the t test for unpaired samples and categorical variables with the chi-square test. The variables that were found to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic regression analysis. In all comparisons, the threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .05.

ResultsWe studied 1575 patients, 661 of whom were women (42%), with a mean age (SD) of 69 (10) years. We included 993 patients in the pre-SPARCL group and 582 in the post-SPARCL group. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of each patient group.

Characteristics of the study sample, by group.

| Group | Pre-SPARCL (n = 993) | Post-SPARCL (n = 582) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 68 (10) | 71 (11) | .0001 |

| Women | 39.1% | 46.9% | .003 |

| AHT | 67.3% | 73.8% | .007 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 36.8% | 43.6% | .008 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 32.4% | 48.9% | .0001 |

| Smoking | 24.7% | 23.8% | NS |

| AF | 20.5% | 24.9% | .044 |

| IHD | 16.3% | 14.7% | NS |

| Stroke | 25.8% | 24.5% | NS |

| PAD | 3.7% | 5% | NS |

| Statins | 18.7% | 86.9% | .0001 |

| High-intensity statin therapy | 58.7% | 62.6% | NS |

AF: atrial fibrillation; AHT: arterial hypertension; IHD: ischaemic heart disease; NS: not significant; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; SD: standard deviation.

The post-SPARCL group presented an older mean age (68 [10] vs 71 [11] in the pre-SPARCL group; P = .0001) and a higher proportion of women (46.9% vs 39.1%; P = .003). Regarding vascular risk factors, the post-SPARCL group presented higher prevalence of dyslipidaemia (48.9% vs 32.5% in the pre-SPARCL group; P = .001), hypertension (73.8% vs 67.3%; P = .008), and diabetes (43.6% vs 36.8%; P = .008). No significant differences were found in history of cardiovascular disease, although the percentage of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) was higher in the second period (24.9% vs 20.5%; P = .044), probably due to the higher mean age of this group.

Statins were prescribed at discharge in 18.7% of pre-SPARCL patients and 86.9% of post-SPARCL patients (P = .0001); an upward trend in the use of statins was observed in both groups (15.2% in 1999, 15.5% in 2000, and 24.6% in 2001; 81.6% in 2014, 88.2% in 2015, and 89% in 2016).

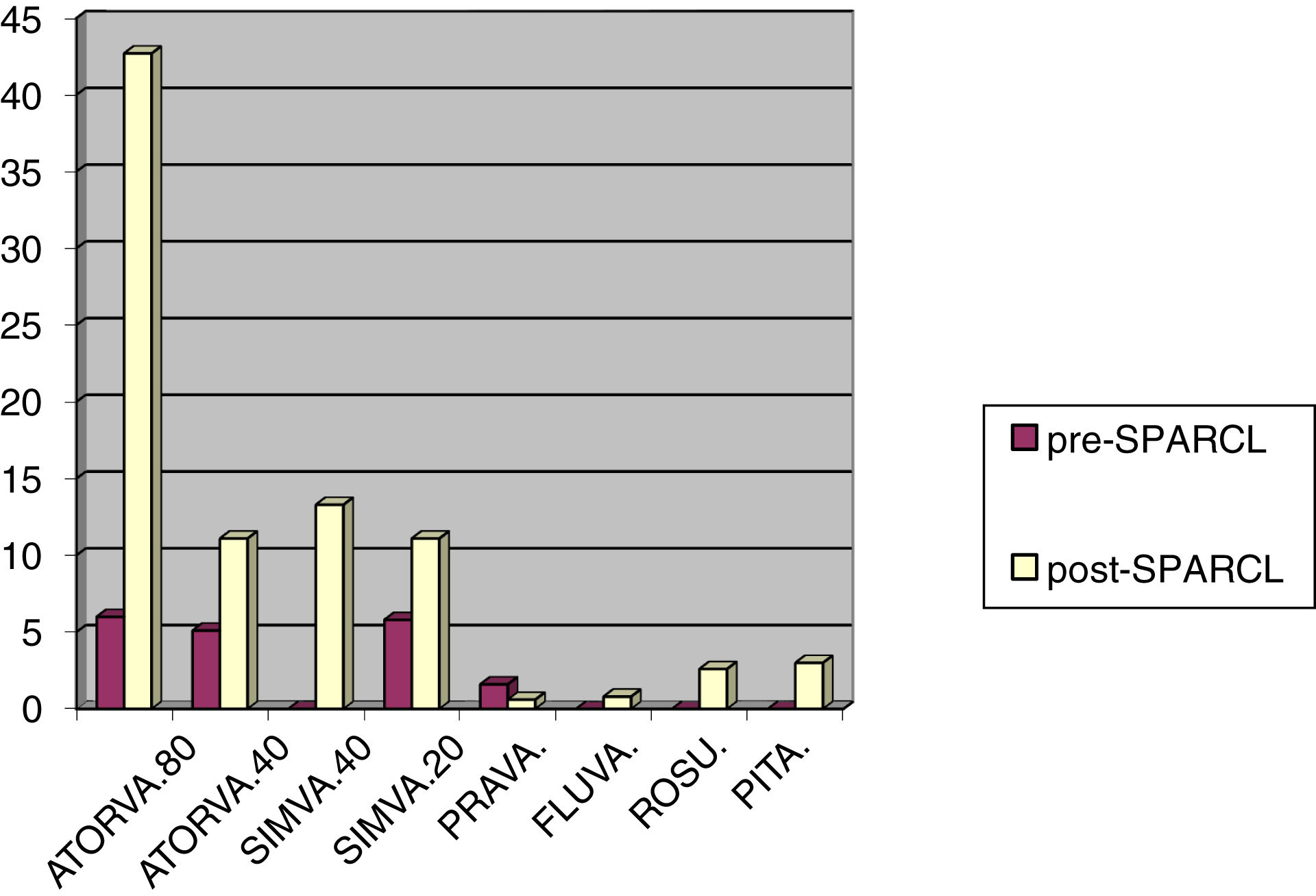

In both groups, the most frequent statin prescribed at discharge was atorvastatin (11.1% in the pre-SPARCL group vs 53.8% in the post-SPARCL group), followed by simvastatin (5.8% vs 25.4%), pravastatin (1.6% vs 0.8%), and fluvastatin (0% vs 1.4%). Finally, rosuvastatin and pitavastatin, 2 statins that were not yet commercially available during the pre-SPARCL period, were prescribed to 2.6% and 3.3% of post-SPARCL patients, respectively. Differences in statin prescription between groups were statistically significant (P = .0001).

Statin prescription data are shown in Fig. 1.

High-intensity statin therapy was prescribed to 11.1% of pre-SPARCL patients and 54.4% of post-SPARCL patients (P = .0001), although the proportion of all patients under statin treatment who received high-intensity therapy was similar in both groups (58.7% vs 62.6%; P > .05).

In the pre-SPARCL group, the univariate analysis found that statin prescription was positively correlated with history of hypercholesterolaemia and ischaemic heart disease, and negatively correlated with age and history of AF. However, only hypercholesterolaemia (positive correlation) and age (negative correlation) were found to be predictors of statin prescription at discharge in the multivariate analysis. In the pre-SPARCL group, the use of high-intensity statin therapy presented the same results in the univariate and multivariate analyses, as few patients received statins, with over half receiving high-intensity therapy.

In the post-SPARCL group, statins were more frequently prescribed to patients with arterial hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia, or history of smoking or cardiovascular disease. However, only hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia continued to show a significant correlation with statin prescription at discharge in the multivariate analysis. The predictors of prescription of high-intensity statin therapy were hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia, with a positive correlation, and age, with a negative correlation. However, in the multivariate analysis, this treatment was positively correlated with history of ischaemic heart disease, and negatively correlated with age.

The results of the multivariate statistical analysis of correlations between patient characteristics and use of statins and high-intensity statin therapy are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Correlation between patient characteristics and statin use. Multivariate analysis.

| Group | Pre-SPARCL (P) | Post-SPARCL (P) |

|---|---|---|

| Factor | ||

| Age | NS | NS |

| Sex | NS | NS |

| AHT | NS | .012 |

| Diabetes mellitus | NS | NS |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | .0001 | .0001 |

| Smoking | NS | NS |

| AFa | .004 | NS |

| IHD | NS | NS |

| Stroke | NS | NS |

| PAD | NS | NS |

AF: atrial fibrillation; AHT: arterial hypertension; IHD: ischaemic heart disease; NS: not significant; PAD: peripheral arterial disease.

Correlation between patient characteristics and use of high-intensity statins. Multivariate analysis.

| Group | Pre-SPARCL (P) | Post-SPARCL (P) |

|---|---|---|

| Factor | ||

| Agea | NS | .001 |

| Sex | NS | NS |

| AHT | NS | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus | NS | NS |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | .0001 | NS |

| Smoking | NS | NS |

| AFa | .021 | NS |

| IHD | NS | .003 |

| Stroke | NS | NS |

| PAD | NS | NS |

AF: atrial fibrillation; AHT: arterial hypertension; IHD: ischaemic heart disease; NS: not significant; PAD: peripheral arterial disease.

Our results show a clear change in the prescription of statins to patients with ischaemic stroke.

The use of statins in this patient group has undergone a four-fold increase, now reaching nearly 90% of all discharged patients.

During the pre-SPARCL period, prescription of statins was limited to patients with hypercholesterolaemia and a smaller number of patients with AF, probably due to the association of this condition with cardioembolic stroke, in which cholesterol plays a less prominent role.

To understand these findings, we should be mindful of the recommendations for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia that were in place during the pre-SPARCL period. In 1999, the AHA/ASA published a set of guidelines for patients with ischaemic stroke,9 recommending a low-fat diet (“AHA step II diet”: < 30% fat, < 7% saturated fat, < 200 mg/day cholesterol) and placing special emphasis on weight management and physical activity; the guidelines recommended adding drug therapy (eg, statins) if LDL-C levels > 130 mg/dL persisted, and considering drug therapy for LDL-C levels of 100-130 mg/dL.

Few studies have evaluated changes in statin prescription patterns after stroke, although a study conducted in the United Kingdom supports our results.10 This was a retrospective cohort study of anonymised data extracted from primary care medical records from 670 primary care physicians in a population of the United Kingdom. In this study, the proportion of patients with ischaemic stroke who were receiving statins within 2 years after the event increased from 25% in 2000 to 70% in 2006; this percentage remained at approximately 75% until 2014.

Another important finding from our study is that the statin dose used continues to be insufficient. Surprisingly, among patients receiving statins, the percentage of patients receiving high-intensity statin therapy was similar in both periods (58.7% vs 62.6%; P > .005). The AHA/ASA guidelines published in 1999 do not specifically recommend high-intensity statin therapy, unlike the 2014 AHA/ASA guidelines for the secondary prevention of stroke,11 which do recommend this treatment (class I, level of evidence B).

In fact, there is growing evidence of the importance of administering high doses of statins for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.

Thus, an association has been observed between cardiovascular events/death due to cardiovascular disease and the level of LDL-C in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACVD) receiving statins. In a recent study including 1854 patients with ACVD who were followed up for nearly 6 years, the risk of a new cardiovascular event and/or death due to cardiovascular disease was significantly higher (31% increase) in patients with an LDL-C level ≥ 100 mg/dL than in those with LDL-C levels <70 mg/dL (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.08-1.59).12

In patients with history of stroke, a subanalysis of the SPARCL trial13 revealed that an LDL-C level < 70 mg/dL was associated with a 28% decrease in the risk of stroke (HR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.59-0.89; P = .0018) without significantly increasing the risk of haemorrhagic stroke (HR: 1.28; 95% CI: 0.78-2.09; P = .3358). Furthermore, in these patients with recent stroke or TIA, a ≥ 50% decrease in LDL-C levels translated into a 31% decrease in the risk of any type of stroke (HR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.55-0.87; P = 0.0016), a 33% decrease in the risk of ischaemic stroke (P = .0018), and a 37% decrease in the risk of major coronary event (P = .0323).

In Japan, the J-STARS study into secondary prevention of stroke included 1578 patients aged 45-80 years with history of non-cardioembolic ischaemic stroke who were randomised to receive either 10 mg/day pravastatin or a placebo and followed-up for a mean of 4.9 years. A subsequent subanalysis of this study found that the risk of stroke and TIA and all vascular events decreased with LDL-C levels of 80-100 mg/dL.14

The recently published guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemia issued by the European Society of Cardiology and the European Atherosclerosis Society are based on the premise that the lower LDL-C levels, the better.15 In fact, in patients at very high risk, with history of ACVD (including ischaemic stroke and TIA), the new target LDL-C level is < 55 mg/dL.

We should also point out that age was found to be an independent predictor of lower likelihood of statin prescription, particularly for high-intensity therapy; this was observed in both of the periods analysed.

Although mean age in the SPARCL trial6 was 63 years, a subsequent subanalysis confirmed the effectiveness of statins in older patients with recent ischaemic stroke.16 In this subanalysis, patients were divided into 2 groups: older adults (≥ 65 years) and younger adults (< 65 years). The study included 2249 older adults, with a mean age of 72.4 years. Of these, 30.9% were ≥ 70 years old, and 4.6% were ≥ 80 years old. The risk of stroke or TIA (HR: 0.79; P = .01), major coronary event (HR: 0.68; P = .035), coronary heart disease (HR: 0.61; P = .0006), and revascularisation (HR: 0.55; P = .0005) also decreased considerably in the older group.

In the retrospective cohort study of primary care medical records mentioned previously,10 older age (≥ 75 years) was also correlated with lower likelihood of treatment with statins and high-intensity statin therapy.

In the light of the above, treatment with statins or high-intensity statin therapy should not be ruled out based solely on patient age; rather, treatment must always be tailored to the patient’s needs.

The limitations of our study include those inherent to retrospective studies, such as under-reporting of patients with ischaemic stroke, and those inherent to its observational design, such as variability of healthcare professionals and patients. However, our study also has multiple strengths, such as its multicentre design (with data from the main 3 hospitals in Seville), detailed data on the type and dose of statins, and the large sample size, providing an accurate reflection of daily clinical practice.

In conclusion, our results show a clear change in the prescription of statins to patients with ischaemic stroke. The publication of the SPARCL trial in 2006, which for the first time provided evidence that high-intensity statin therapy may significantly reduce stroke recurrence in patients with history of stroke and no coronary heart disease, was a turning point in the treatment of these patients. In fact, statins have emerged as a cornerstone of the pharmacological treatment of stroke.

As shown in this study, the use and dose of statins have increased considerably in recent years. However, a high percentage of patients with ischaemic stroke continue to be undertreated; statin use should be further optimised in this patient group.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.