Kleine-Levin syndrome is an infrequent neuropsychiatric disorder that manifests with recurrent, self-limited episodes of hypersomnia, normally accompanied by behavioural alterations (hypersexuality, irritability, and aggressiveness) and such cognitive alterations as confusion and hallucinations. It presents in the second decade of life, with a higher incidence in young men (4:1). Episodes last from 1 to 2 weeks, with complete remission of symptoms. Episodes may occur several times per year, separated by asymptomatic periods.1

We present the case of a 17-year-old patient who, after symptoms of increased bowel activity, nausea, and low-grade fever, began to present a marked increase in somnolence, sleeping up to 20hours per day; he was admitted to the internal medicine department. During his hospital stay, he underwent a blood test, head CT scan, brain MRI scan, chest and abdomen CT scan, EEG, polysomnography, and waking EEG; none revealed significant findings. The multiple sleep latency test revealed a mean sleep latency above 10min (14min) and did not show REM sleep in any sleep attempt. The CSF study showed a mildly elevated protein level. Considering a possible emotional origin, the psychiatry department assessed the patient on 3 occasions, with no abnormal findings and no dysfunction in the school or family setting.

Since the patient did not meet criteria for narcolepsy or idiopathic hypersomnia, and considering the history of gastrointestinal involvement and high CSF protein level, he was discharged with an initial diagnosis of post-infectious encephalitis, not ruling out other secondary origins of the symptoms. We started empiric outpatient treatment with prednisone on a tapering schedule, starting at 70mg and decreasing by 10mg/week.

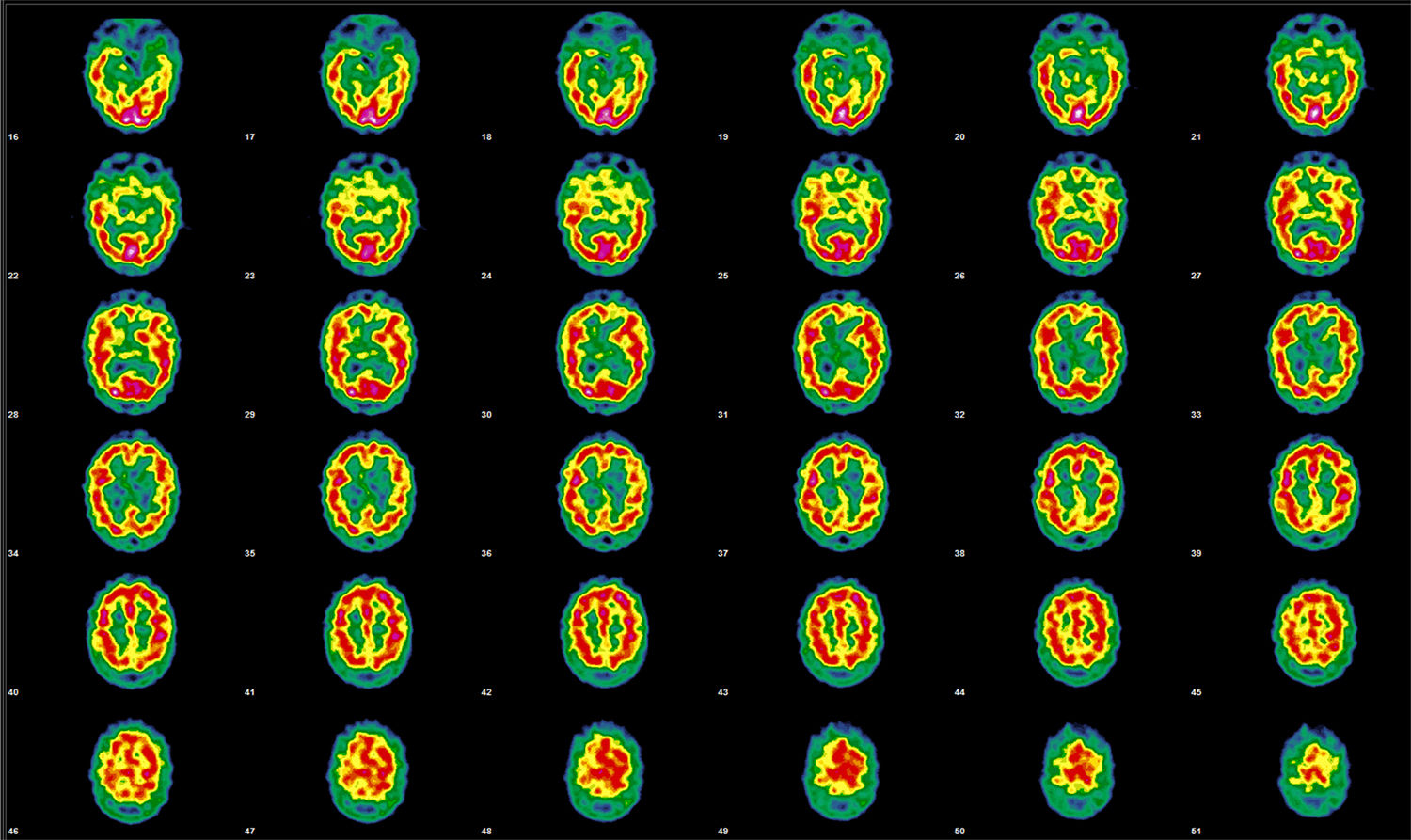

Several days later, he was admitted to the neurology department due to excessive hours of daytime sleep (up to 20hours per day). Considering his tendency to sleep, hyperphagia, and behavioural alterations during wakefulness, and the presence of a gastrointestinal infection as the trigger factor for the symptoms, he was diagnosed with recurrent encephalitis. A brain perfusion SPECT scan revealed a cortical activity pattern not corresponding with the patient's age; the alterations observed were compatible with clinical suspicion of Kleine-Levin syndrome (Fig. 1).

Initial brain perfusion SPECT performed after the administration of 925MBq of 99mTc-HMPAO. Representative transaxial tomographic slices are shown. Qualitative assessment detected irregular cortical function in both hemispheres, with more marked hypoactivity in the anterior and orbitofrontal regions, and in the right mesial temporal region. The left hemisphere showed defects in the orbitofrontal, temporobasilar, and mesial regions. Asymmetry is observed in the basal nuclei, with decreased activity on the right side; the cerebellum is unaffected.

After a significant clinical improvement, the patient was discharged with treatment with modafinil (100mg/day); on some days he continued to experience mild excessive daytime sleepiness, although to a lesser degree than during admission.

Two months later he once more developed symptoms of hypersomnia, which improved when the dose of modafinil was increased (200mg/day).

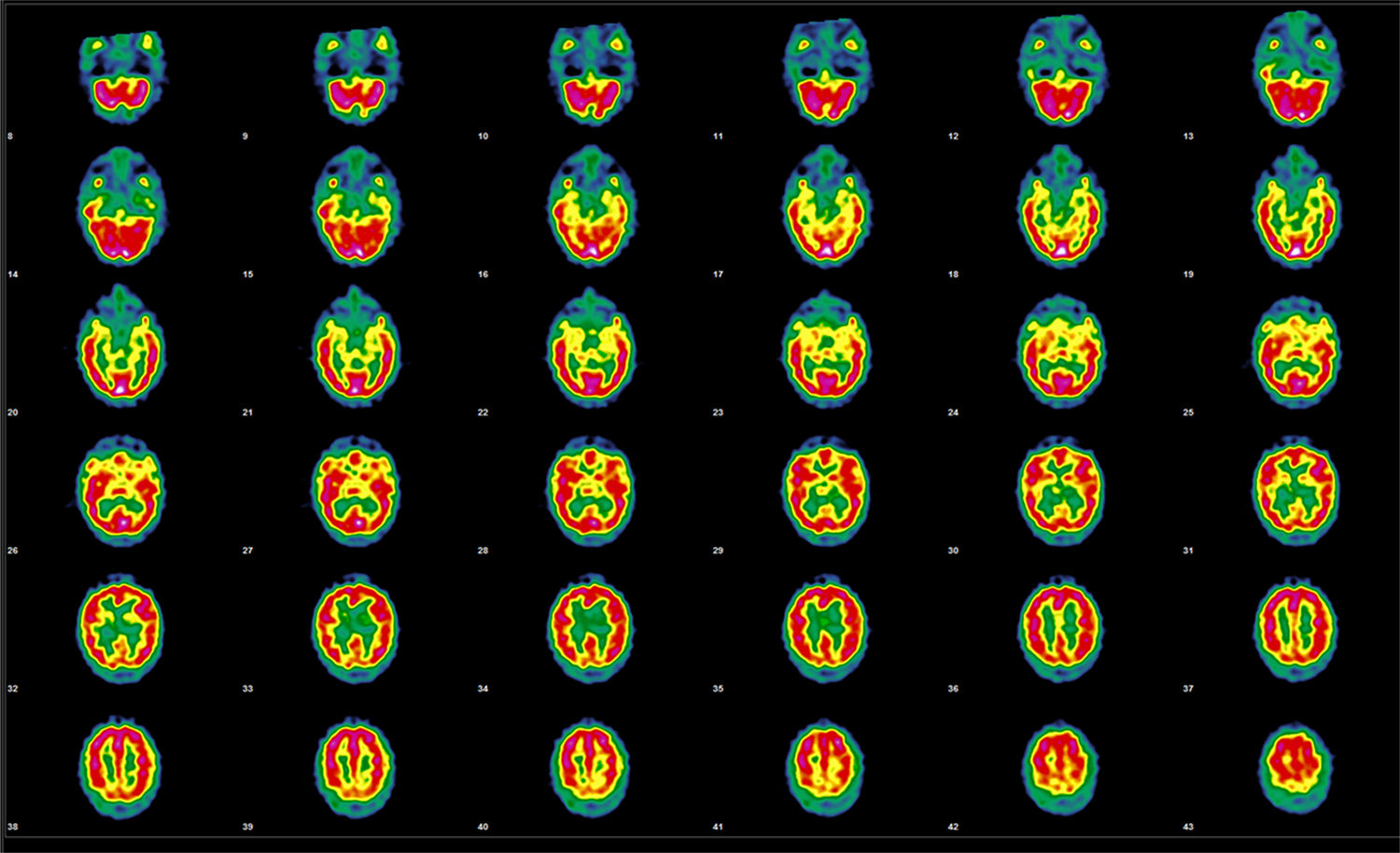

During the 2-year follow-up, the patient presented a further 3 episodes of similar characteristics. A SPECT study performed 2 years after symptom onset revealed normal uptake in the frontal area and persisting alterations in the temporal region (Fig. 2).

Follow-up brain perfusion SPECT performed after the administration of 925MBq of 99mTc-HMPAO, 20 months after the initial study. Representative transaxial tomographic slices are shown. Irregular cortical function is observed in both hemispheres, with defects of higher intensity in the orbitofrontal and temporal regions and small, diffusely distributed irregularities in the remaining areas of both hemispheres; no alterations are observed in the basal nuclei or cerebellum. Compared with the previous studies, an improvement is observed in the defects in the orbitofrontal and temporal regions, with normal uptake in the anterior frontal region.

Kleine-Levin syndrome is a rare disease whose diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms.2 To date, no objective complementary tests able to confirm its diagnosis have been developed. Our patient presented successive episodes of self-limited hypersomnia, with no significant findings in any of the complementary tests performed during admission.

Aetiology of Kleine-Levin syndrome remains unknown and clinical symptoms suggest the possibility of a hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction caused by such trigger factors as head trauma, aseptic meningoencephalitis, or Prader-Willi syndrome. Onset during adolescence, symptom recurrence, and infections as frequent trigger factors suggest an autoimmune aetiology; furthermore, an association between Kleine-Levin syndrome and HLA-DR1 has been observed.3 The trigger factor (gastroenteritis) and the age of onset in our patient coincide with descriptions in the literature.

Differential diagnosis should include recurrent major depression, bipolar depression, and recurrent neurotic or organic hypersomnias, which are mainly caused by intraventricular tumours in the third or fourth ventricle.4

To rule out a personality disorder as the origin of the symptoms, it is essential to perform a psychological study during the clinical episode and the asymptomatic period. No psychiatric disorder was observed in our patient.

Functional imaging has been shown to be useful for studying the pathophysiology of the condition.5

During the symptomatic phase, SPECT typically reveal hypoperfusion in the uni- or bilateral temporal region, frontotemporal region, and basal ganglia.6 Such dysfunction may constitute a diaschisis phenomenon, favoured by frontal hypoactivation derived from diencephalic dysfunction. In our case, SPECT revealed hypoperfusion in the right basal ganglia, both temporal regions, and the right frontotemporal region.

In interictal periods, results from the studies performed suggest that SPECT findings usually normalise, but temporal alterations persist even after clinical alterations have disappeared. Findings from the second SPECT study were pathological, although the patient presented no symptoms; this is consistent with the results reported by Gabrieli et al.3

We conclude that brain perfusion SPECT should be considered during episodes of recurrent hypersomnia in adolescents to rule out a possible associated Kleine-Levin syndrome.

Please cite this article as: Ramírez Ocaña D, Espinosa Muñoz E, Puentes Zarzuela C. Utilidad del SPECT cerebral en el estudio de la hipersomnia recurrente: síndrome de Kleine-Levin. Neurología. 2019;34:621–623.