Parkinsonism is defined as bradykinesia with rest tremor, rigidity, and/or postural instability. The etiology in most cases is idiopathic parkinson's disease (PD), but a subset of patients exhibits atypical features such as: frequent early falls, ocular motility dysfunction, dysautonomias, ataxia, and early dementia which represent a diagnostic challenge. These red flags and exclusion criteria for PD raise the possibility of secondary parkinsonism (drug-induced, vascular) or atypical parkinsonisms (progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple systemic atrophy, corticobasal syndrome, and dementia with lewy bodies).

Progressive supranuclear palsy was first described in 1964 based on a series of adult patients with a rapid neurodegenerative disease and unusual features. A clinical syndrome that, in its classic phenotype, includes supranuclear gaze palsy, postural instability, and dementia, known as Richardson syndrome—PSP-RS.1–3 Other common variants have been identified including: PSP with gait freezing (PSP-PGF), PSP with predominant Parkinsonism (PSP-P), PSP with frontal presentation (PSP-F), among others.3–5 Pathologically it is characterized by the accumulation of 4-repeat (4R) tau protein in the form of neurofibrillary tangles, oligodendrocytic coils, and tufted astrocytes located predominantly at the globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, and substantia nigra.4,6–8 At present, a definitive diagnosis requires neuropathological assessment as there are no reliable markers. A “probable” or “possible” diagnosis based on clinical grounds is done with the presence of either supranuclear gaze palsy or a combination of slow vertical saccades and postural instability with falls within the first year.

While PSP is recognized mainly as a sporadic syndrome, a small subset of cases of familial PSP have been described with single-gene mutations of genes that encode the TAU and LRRK2 (Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2) proteins.7,9,10 These patients often have an early-onset parkinsonism that increases the likelihood of an inherited etiology.

We report the case of a patient with behavioral changes and parkinsonism that started at 53 years of age with a familiar history of early onset dementia. The variant c.915T > C (p. S305S) of the MAPT gene that encodes the microtubule-associated protein tau, confirmed the diagnosis of a parkinsonian variant within the spectrum of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP-P).

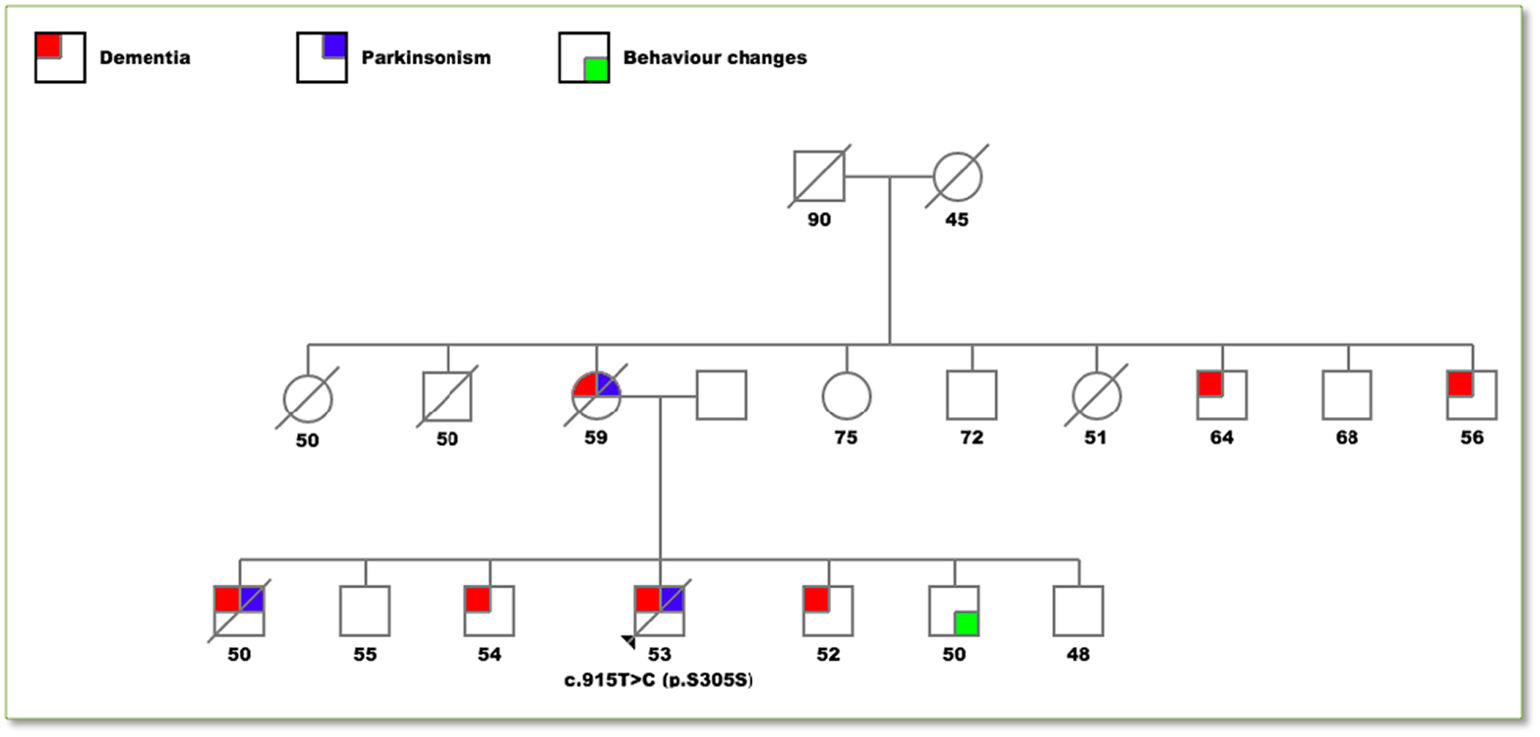

Clinical caseA 56-year-old male was seen at the outpatient neurology clinic for a chief complaint of behavioral changes and abnormal movements. The patient had been in his usual until 3 years before this presentation when perseverance, emotional lability, disinhibition and echolalia developed. Two years ago, the family began to notice bradykinesia, rigidity and down gaze palsy ultimately reaching complete dependence for activities of daily living. He had a positive family history of early-onset dementia and/or parkinsonism in 4 of his 6 siblings and his mother (see Fig. 1).

Pedigree drawing of the family.

Colored squares represent affected individuals differentiated in: dementia (red), parkinsonism (blue) and behavior changes (green). The numbers below each individual represent the age at the onset of symptoms or in the asymptomatic members their actual age. The only individual genetically analyzed was the proband with the p.S305S mutation. A diagonal line indicates that the individual is deceased.

Upon admission, the patient was disoriented, with a non-fluent aphasia but a tendency for echolalic speech. He had supranuclear gaze palsy, pseudobulbar affect, bradykinesia, rigidity, and parkinsonian gait. A levodopa trial (carbidopa/levodopa) was initiated for 9 months without response.

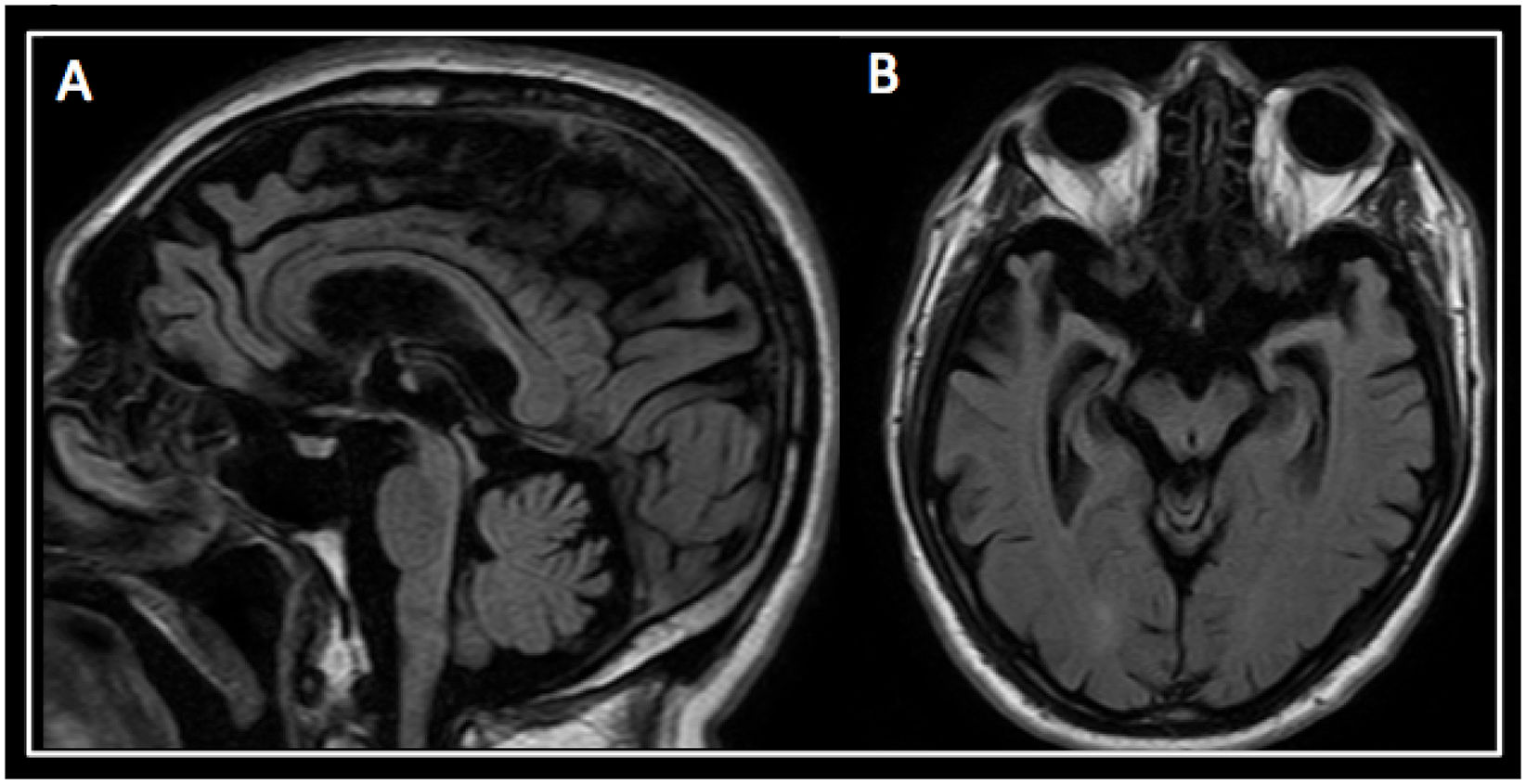

A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed marked atrophy of the hippocampus, temporal lobes, and peri-rolandic cortex. Atrophy of the midbrain tegmentum with a marked convexity was also seen (see Fig. 2).

Six months later, the patient was completely dependent on all daily life activities. A next-generation sequencing assays panel (NGS) was performed. The genetic test reported a heterozygous variant c.915T > C (p. S305S), classified as pathogenic in the gene that encodes the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) in the chromosome 17. Unfortunately, the patient died a month after this third evaluation.

DiscussionOur patient presented with atypical parkinsonian features with resistance to levodopa trial and midbrain atrophy at imaging. The familiar history was the key element for considering an inherited etiology that made the accurate diagnosis.

The early and reliable diagnosis of PSP represents a clinical challenge. The clinical criteria proposed by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) is the most widely used for diagnosis. The combinations of early postural instability with falls and vertical ocular supranuclear gaze palsy have an adequate specificity (95%–100%) for probable classic phenotype PSP (Richardson syndrome). However, it has low sensitivity in the first years of the disease, as well as for other variants.11

The neuropathological hallmark is the presence of abnormal accumulation of tau protein which is encoded by the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) gene. This gene has a microtubule-binding domain with 3 or 4 repeats of 31 amino acids that bind to the heterodimers of α- and β-tubulin that in a polymerized form constitute the microtubules. In PSP, the concentration of 4-repeat (4R) tau increases.4,8 Mutations in the MAPT gene located on chromosome 17 have been associated with frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism, classified as primary tauopathy.6 The H1 subtype c (H1c) haplotype of the MAPT gene increases the risk of developing PSP. Other genetic risk factors described include alleles in STX6 and EIF2AK3.10

Although PSP is generally considered as sporadic, there is increasing evidence to suggest that several genetic variants affect sporadic and familial forms of PSP.5,7 Genetic variants with mutations in the MAPT gene, are the most common cause of familial PSP.7,10,11 There have been identified more than 60 mutations in the MAPT gene in patients presenting with parkinsonism and frontotemporal dementia and at least 15 mutations for PSP phenotype. Within this last subgroup, there is the p. S305S mutation, that corresponds to the one found in our patient 7,10,12P. S305S mutation located in exon 10 is related to a conformational alteration of the tau protein preventing its degradation,10 and resulted in increase of splicing of exon 10 and higher levels of 4 repeat tau.13,14

Interestingly, there was a clear variability of the clinical phenotype between family members. As described by Stanford et al., presentations can be diverse within the same mutation of the tau gene. This statement suggests it is important to consider other non-genetic factors that may influence the expression of the disease.13 Studies support clinical and pathological variation between families with mutations in tau gene.12,13 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of this mutation in Latin America.

For patients with a “probable” or “possible” diagnosis of PSP with early onset of symptoms and/or a familiar history of dementia or abnormal movements, complementary genetic studies are essential for establishing the etiology. This information can aid in establishing a more accurate prognosis and the risk for asymptomatic relatives. Likewise, the understanding of genetic factors can help to elucidate the pathogenesis of the disease and evaluate new therapeutic strategies directed to specific pathways that may change the natural history of the disease.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation as well as to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

FundingThe work done with its resources, in addition to the volunteer work of the researchers.

Ethical approvalThe local ethics committee approved the study of the institution. The legal guardian of the patient gave his informed consent in writing for the publication of the case.