Chronic cough can impair quality of life, with serious biomedical and psychosocial impacts. This condition should be managed well by physicians at primary health care level.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the approach of primary physicians in the management of chronic cough.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional study was conducted using an interviewer-administered questionnaire from September 2018-March 2019 in Najran City, Saudi Arabia. All primary physicians (n=134) working at different primary health care facilities during the study period who agreed to participate were included.

ResultsThe prevalence of chronic cough at primary physician's practice was 25%. The study revealed around 61% of primary physicians (n=134) have good clinical experience of the management of chronic cough despite the widespread of clinical guidelines. They make definitive diagnosis of chronic cough as following; 66% based on history &physical examination,61% based on further tests and 60% based on response to empiric therapy. They diagnose their cases secondary to allergy (63%), inflammation (60%), infection (59%), medications (42%) and malignancy (33%). The study showed inadequacy of participants in treating the chronic cough; 63% prescribe a decongestant & an antihistamine for upper airway cough syndrome (UACS), 81% prescribe an inhaled bronchodilators or corticosteroids for asthma, 79% prescribe an antacid agent for gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) and 60% refer to specialized clinic. About 46% of participants approach the child with chronic cough as same as adult approach.

ConclusionChronic cough is high prevalent in practice of primary care physicians. Although the widespread dissemination of management guidelines of chronic cough, the inadequacy in clinical practice of primary physicians still occurs. Design educational programs and increased awareness for patients and their families about chronic cough are responsible solutions.

La tos crónica puede afectar a la calidad de vida con impactos biomédicos y psicosociales graves. Esta enfermedad debe ser bien manejada por los médicos a nivel de atención primaria.

ObjetivoEvaluar el abordaje de la tos crónica por parte los médicos de atención primaria.

Materiales y métodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio transversal utilizando un cuestionario realizado por un entrevistador de septiembre de 2018 a marzo de 2019 en la ciudad de Najran, Arabia Saudita. Se incluyeron todos los médicos de atención primaria (n=134) que aceptaron participar y que trabajaban en diferentes centros de atención primaria durante el período de estudio.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de la tos crónica en la consulta de atención primaria fue del 25%. El estudio reveló que solo alrededor del 61% de los médicos de atención primaria (n=134) tienen una buena experiencia clínica en el manejo de la tos crónica a pesar de la distribución de guías clínicas. Establecen un diagnóstico definitivo de tos crónica de las siguientes formas: el 66% según la historia clínica y el examen físico, el 61% se basa en pruebas adicionales y el 60% se basa en la respuesta al tratamiento empírico. Diagnostican sus casos secundarios a alergia (63%), inflamación (60%), infección (59%), medicamentos (42%) y neoplasias malignas (33%). El estudio mostró una falta de competencia de los participantes en el tratamiento de la tos crónica; el 63% prescribe un anticongestivo y un antihistamínico para el síndrome de la tos crónica asociado a vía aérea superior (STCAVAS), el 81% prescribe broncodilatadores o corticosteroides inhalados para el asma, el 79% prescribe un antiácido para la enfermedad por reflujo gastroesofágico (ERGE) y el 60% refiere al paciente a la consulta especializada. Alrededor del 46% de los participantes se enfrentan al niño con tos crónica igual que hacen con el adulto.

ConclusiónLa tos crónica es altamente prevalente en la consulta de los médicos de atención primaria. A pesar de la amplia distribución de guías de manejo de la tos crónica, todavía se da una práctica clínica inadecuada por parte de los médicos de atención primaria. Diseñar programas educativos y una mayor concienciación de los pacientes y sus familias sobre la tos crónica son soluciones responsables.

Primary care physicians offer the ability to manage difficult and complex health problems, such as chronic cough; however, there are many potential etiologies of this condition and wide variation in management approaches.

In adults, chronic cough has been defined as lasting for more than 8 weeks, while in children, cough is considered chronic if present for more than 4 weeks.1,2 Persistent and excessive coughing is considered a significant problem that can impair quality of life and lead to serious biomedical and psychosocial effects. It is associated with a high burden of recurrent health facility visits, personal and family stress, and social embarrassment. It is found that >80% of parents had sought five or more medical consultations for their child with chronic cough in one year.3 Physical impairment, psychological upset, school or work absenteeism, and a substantial direct and indirect economic burden are bad impacts of chronic cough.4 The morbidity of chronic cough is reported at between 3% and 40% of the population and represents a substantial epidemiological burden with a high global prevalence (10–20% in the general adult population) as well as a major unmet medical need.5,6

There are many causes for chronic cough. The most cases can be accounted for by upper airway cough syndrome (UACS), gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), asthma, and non-asthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis (NAEB).7

Ideally, chronic cough is managed as the manifestation of disease rather than by symptomatic therapy. The width and diversity of etiologies from self-limited to lethal diseases, such as like lung cancer, represent a challenge to the clinical practitioner. The medical expert and well-qualified physician represent the cornerstone of good care and best practice either in curing the chronic cough or minimizing its sequelae and recurrence. An estimated 90% of cases of chronic cough can be worked-up efficiently by a primary physician using a standard protocol based on updated evidence that empowers a primary physician in managing the chronic cough effectively.8 Although the systematic clinical reasoning is the ultimate management approach for chronic cough, most of primary care physicians do not adhere to recommended guidelines.9 Misdiagnosis, over-investigation, irrational medication and inappropriate referral are all examples of malpractice in dealing with chronic cough.

In this study, we evaluated the approach of primary physicians in the management of chronic cough in Najran City, Saudi Arabia. This will be beneficial in strengthening the role of primary care services in solving complex health problems such as chronic cough.

Materials and methodsThis study was conducted using a descriptive and analytic cross-sectional survey design from September 2018 to March 2019 in Najran City, in southwestern Saudi Arabia. The primary health services in this region are provided by many governmental and private facilities.

The study population consisted of all primary physicians practicing in different specialties; general practitioner, emergency medicine, family medicine, general internal medicine and general pediatric medicine. We had included all primary physicians (n=134) working at different health services facilities (Ministry of Health [MOH], University Health Services, Military Health Services, National Guard Health Services, Interior Ministry Health Services and Private Health Services) during the study period who agreed to participate; those who declined to participate were excluded.

Researchers constructed a three-parts questionnaire to collect the data (supplementary material). Section 1 was designed to collect data for the most relevant sociodemographic variables of participants, including sex, age, nationality, marital status, job title, medical specialty, qualifications, work place, health care facility, and years of experience. Section 2 consisted of a clinical audit of the total number of patients per clinic and the number of patients presenting with chronic cough per clinic. Section 3 has made in form of self-evaluation for participants regarding their practice in management of chronic cough. It consisted of 20 items (Appendix A) designed to collect data about the primary physicians’ approach to chronic cough. Three phrases about diagnosis, 5 phrases about etiology,10 phrases about treatment and 2 phrases about consideration of differences between adult and child age groups. A 5-point Likert scale was adopted to qualify answers ranging from (1) for (Strongly Disagree) up to degree (5) for (Strongly Agree).

The questionnaire's content and relevance have been tested for their appropriateness, reliability. The content validity had evaluated on reviewing all scale items by three experts and any suggested modifications were done. We use the internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha (supplementary material). The calculated Cronbach's Alpha was (0.789.) for the whole questions which had (5-Point Likert scale) of the questionnaire; these results indicate acceptable reliability for the questionnaire.

Data was collected through face-to-face delivery mode. Then fed to The Statistical Package for Social Sciences program (SPSS v.23) after checking and coding. The basic features of the data in the study had analyzed through frequencies, percentages, mean and standard deviation.

ResultsThe aim of study was to examine the clinical approach of primary physicians in the management of chronic cough.

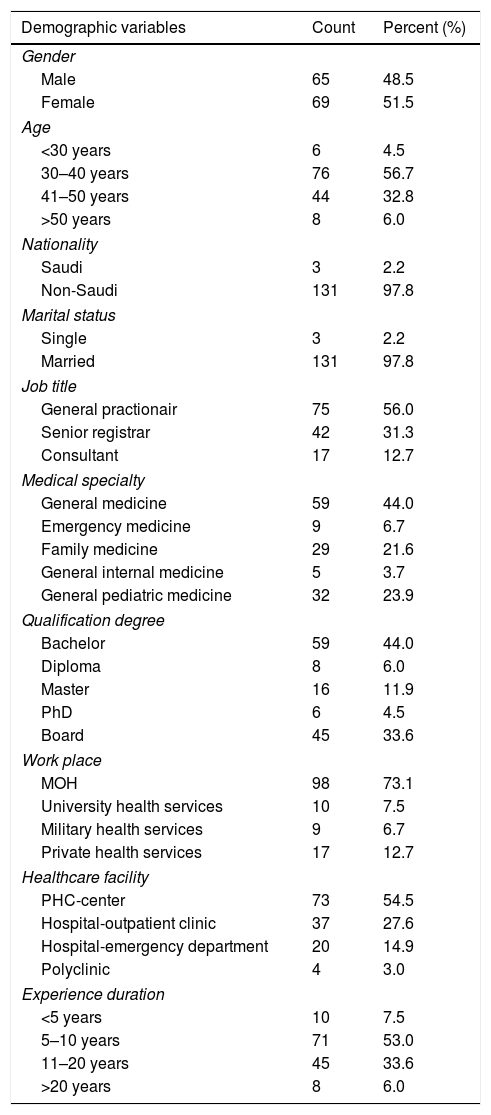

All participants (N=134) had completed the interview administrated questionnaire. The mmajority (97.8%) of them were non-Saudi, of which 51.5% were female, 97.8% were married and 56.7% were in the 30 to 40 years age group. In terms of medical specialty, 44% of the participants practiced general medicine, 44% held a bachelor's degree only, 73.1% work in the MOH and 54.5% were employed at primary health care (PHC) centers. More than half (53%) of the total participants had 5–10 years of clinical experience. On average, participants had managed 24 patients per clinic, where six of patients had chronic cough. All details about baseline characteristics of the sample shown in Table 1.

Demographic data of the sample study (N=134).

| Demographic variables | Count | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 65 | 48.5 |

| Female | 69 | 51.5 |

| Age | ||

| <30 years | 6 | 4.5 |

| 30–40 years | 76 | 56.7 |

| 41–50 years | 44 | 32.8 |

| >50 years | 8 | 6.0 |

| Nationality | ||

| Saudi | 3 | 2.2 |

| Non-Saudi | 131 | 97.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 3 | 2.2 |

| Married | 131 | 97.8 |

| Job title | ||

| General practionair | 75 | 56.0 |

| Senior registrar | 42 | 31.3 |

| Consultant | 17 | 12.7 |

| Medical specialty | ||

| General medicine | 59 | 44.0 |

| Emergency medicine | 9 | 6.7 |

| Family medicine | 29 | 21.6 |

| General internal medicine | 5 | 3.7 |

| General pediatric medicine | 32 | 23.9 |

| Qualification degree | ||

| Bachelor | 59 | 44.0 |

| Diploma | 8 | 6.0 |

| Master | 16 | 11.9 |

| PhD | 6 | 4.5 |

| Board | 45 | 33.6 |

| Work place | ||

| MOH | 98 | 73.1 |

| University health services | 10 | 7.5 |

| Military health services | 9 | 6.7 |

| Private health services | 17 | 12.7 |

| Healthcare facility | ||

| PHC-center | 73 | 54.5 |

| Hospital-outpatient clinic | 37 | 27.6 |

| Hospital-emergency department | 20 | 14.9 |

| Polyclinic | 4 | 3.0 |

| Experience duration | ||

| <5 years | 10 | 7.5 |

| 5–10 years | 71 | 53.0 |

| 11–20 years | 45 | 33.6 |

| >20 years | 8 | 6.0 |

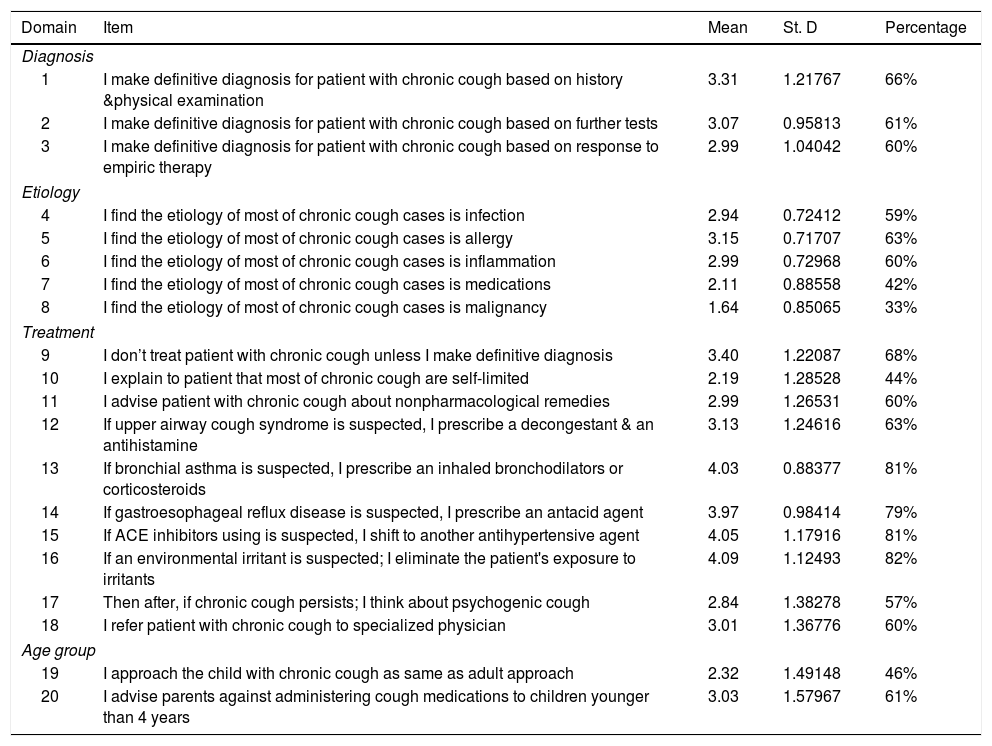

Table 2 represents frequencies and percentages, mean and standard deviation of clinical approach of primary physicians in the management of chronic cough. The highest percentage(82%) was awarded to the phrase (If an environmental irritants is suspected; I eliminate the patient's exposure to irritants) with mean score (4.09) out of (5) and Std. Deviation (1.12493), followed by (If ACE inhibitors using is suspected, I shift to another antihypertensive agent) with mean score (4.05), followed by (If bronchial asthma is suspected, I prescribe an inhaled bronchodilators or corticosteroids) with mean score (4.03) while the lowest percentage (33%)was awarded to the phrase (I find the etiology of most of chronic cough cases is malignancy) with mean (1.64) out of (5) and Std. Deviation (0.85065).The following table shows all detailed of these results.

Descriptive statistics of clinical approach of primary physicians to chronic cough (N=134).

| Domain | Item | Mean | St. D | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | ||||

| 1 | I make definitive diagnosis for patient with chronic cough based on history &physical examination | 3.31 | 1.21767 | 66% |

| 2 | I make definitive diagnosis for patient with chronic cough based on further tests | 3.07 | 0.95813 | 61% |

| 3 | I make definitive diagnosis for patient with chronic cough based on response to empiric therapy | 2.99 | 1.04042 | 60% |

| Etiology | ||||

| 4 | I find the etiology of most of chronic cough cases is infection | 2.94 | 0.72412 | 59% |

| 5 | I find the etiology of most of chronic cough cases is allergy | 3.15 | 0.71707 | 63% |

| 6 | I find the etiology of most of chronic cough cases is inflammation | 2.99 | 0.72968 | 60% |

| 7 | I find the etiology of most of chronic cough cases is medications | 2.11 | 0.88558 | 42% |

| 8 | I find the etiology of most of chronic cough cases is malignancy | 1.64 | 0.85065 | 33% |

| Treatment | ||||

| 9 | I don’t treat patient with chronic cough unless I make definitive diagnosis | 3.40 | 1.22087 | 68% |

| 10 | I explain to patient that most of chronic cough are self-limited | 2.19 | 1.28528 | 44% |

| 11 | I advise patient with chronic cough about nonpharmacological remedies | 2.99 | 1.26531 | 60% |

| 12 | If upper airway cough syndrome is suspected, I prescribe a decongestant & an antihistamine | 3.13 | 1.24616 | 63% |

| 13 | If bronchial asthma is suspected, I prescribe an inhaled bronchodilators or corticosteroids | 4.03 | 0.88377 | 81% |

| 14 | If gastroesophageal reflux disease is suspected, I prescribe an antacid agent | 3.97 | 0.98414 | 79% |

| 15 | If ACE inhibitors using is suspected, I shift to another antihypertensive agent | 4.05 | 1.17916 | 81% |

| 16 | If an environmental irritant is suspected; I eliminate the patient's exposure to irritants | 4.09 | 1.12493 | 82% |

| 17 | Then after, if chronic cough persists; I think about psychogenic cough | 2.84 | 1.38278 | 57% |

| 18 | I refer patient with chronic cough to specialized physician | 3.01 | 1.36776 | 60% |

| Age group | ||||

| 19 | I approach the child with chronic cough as same as adult approach | 2.32 | 1.49148 | 46% |

| 20 | I advise parents against administering cough medications to children younger than 4 years | 3.03 | 1.57967 | 61% |

Study showed that primary physicians (n=134) have approached 25% of their patients with chronic cough, which is slightly higher than the prevalence (22%) in the same setting.10 This finding reflected how common the chronic cough as primary health condition that needs a systematic and integrated approach.

A thorough medical history and physical examination are paramount in the diagnosis of chronic cough. Based on that physician can develop a proper diagnosis and treatment and limit unnecessary testing.11 We found the primary physicians (n=134) made definitive diagnosis of chronic cough as following; 66% based on history &physical examination,61% based on further tests and 60% based on response to empiric therapy. This underscores the importance of the primary physician's role in the initial assessment of chronic cough to place a differential diagnosis, select appropriate test, make a provisional diagnosis and empirical therapy.

The most common etiologies to be considered in the management of patients >15 years of age with cough lasting >8 weeks; (UACS) secondary to rhino sinus diseases, asthma, (NAEB) and (GERD).12 Other etiologies include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) use, environmental triggers, tobacco use, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and obstructive sleep apnea. In children, most cases can be accounted for by three conditions: asthma, protracted bacterial bronchitis, and upper airway cough syndrome.7 One study proposed a clinical method to detect the causes of chronic cough in a primary care setting found (35.9%) post-infectious cough while (ACE-I) induced cough (12.0%). There were only (1.7%) cases of possible lung cancer.13 Through the practice of the study sample, it was clear from primary physician's diagnostic performance that most cases are allergy (63%), inflammation (60%) and infection (59%) and these findings are in line with the most common causes, while the accounted case for medications (42%) and malignancy (33%) are not. This requires more care to enable primary care physicians to know the most common causes of chronic cough, taking into account other lesser-known causes, as well as training them to differentiate between them, whether in history, clinical examination or the necessary tests.

Although empirical therapy is useful in confirming or excluding the final diagnosis of chronic cough, those who use this strategy to treat chronic cough represented 68% of study sample. Treatment guidelines for chronic cough recommend to direct appropriate trials for the most common causes of cough (i.e., UACS, asthma, NAEB, and GERD) in systematic manner. Subsequently assessment of response to that (full, partially or not) should be instituted.14

The study revealed that about 44% of primary care physicians consider chronic cough to be a temporary problem, and thus violated the definition of chronic cough, which provides for the continuity of cough for more than 8 weeks. This reflects the confusing between acute and chronic cough in terms of definition and etiology as well as the nature of treatment. Sixty percent of them advised their patients with chronic cough about nonpharmacological remedies, ignoring the patient's growing suffering in many domains; physical, psychological, and social. Patients with chronic cough frequently report musculoskeletal chest pains, sleep disturbance, vomiting, and stress incontinence. The psychosocial impact of cough includes a high prevalence of depressive symptoms and worry about serious underlying diseases, difficulty in social life, and disruption of employment can occur.15

The study showed inadequacy of primary care physicians in treating the most common causes of chronic cough, as follows: 63% prescribe a decongestant & an antihistamine for (UACS), 82% eliminate the patient's exposure to environmental irritants, 81% prescribe an inhaled bronchodilators or corticosteroids for asthma, 79% prescribe an antacid agent for (GERD) and around 81% shift to another antihypertensive agent If ACE inhibitors using is suspected. It was remarkable that about 60% of primary care physicians refer patient with chronic cough to specialized clinic. This is irrational referral unless initial treatment was approached including proper history-taking, physical examination, chest x ray and empirical therapy. A study conducted in Singapore on such cases showed that 65% of the referred cases were diagnosed at the first visit through the patients’ detailed history-taking, physical examination and chest radiography.16

While, the habit cough or psychogenic cough is rare cause and its diagnoses can be made only after an extensive evaluation is performed to rule out uncommon causes of chronic cough, and when cough improves with behavior modification.17 Study showed 57% of primary care physicians think about psychogenic cough if chronic cough persists; and this is not logical thinking.

Despite cough in children is labeled as chronic if present for more than 4 weeks instead of 8 weeks. The approach for chronic cough should be different to those in adults as the etiological factors and some medications used for cough in adults have little role in children and might lead to adverse reactions and toxicity.18 Study results revealed 46% of participants approach the child with chronic cough as same as adult approach while only 61% of participants advise parents against cough medications for children.

Taking into account the design of study and sample size, the study reveals that around 61% of primary physicians have good clinical experience of the management of chronic cough despite the widespread release of simplified clinical practice guidelines. Designing and implementing education programs about the best approach of chronic cough could help physicians in primary care for better management.

ConclusionIt is noticeable how common chronic cough is in the practice field of primary care physicians. Although the widespread dissemination of management guidelines of chronic cough, there is variations in approach to chronic cough among primary care physicians. So, design educational programs about chronic cough management is a responsible solution for inadequacy in the clinical practice of primary physicians. Furthermore, the increased awareness of patients and their families about chronic cough is an achievable objective that could improve care and limit financial and social burden. Finally, more and more investigation is required by scholars and leaders in the medical field to resolve a disconnect between the recommended scientific guidelines and the practice of clinicians at primary care level.

Conflict of interestThe author declares that he has no conflict of interest.