To reach a multidisciplinary consensus on the management of patients with advanced COPD using Delphi methodology.

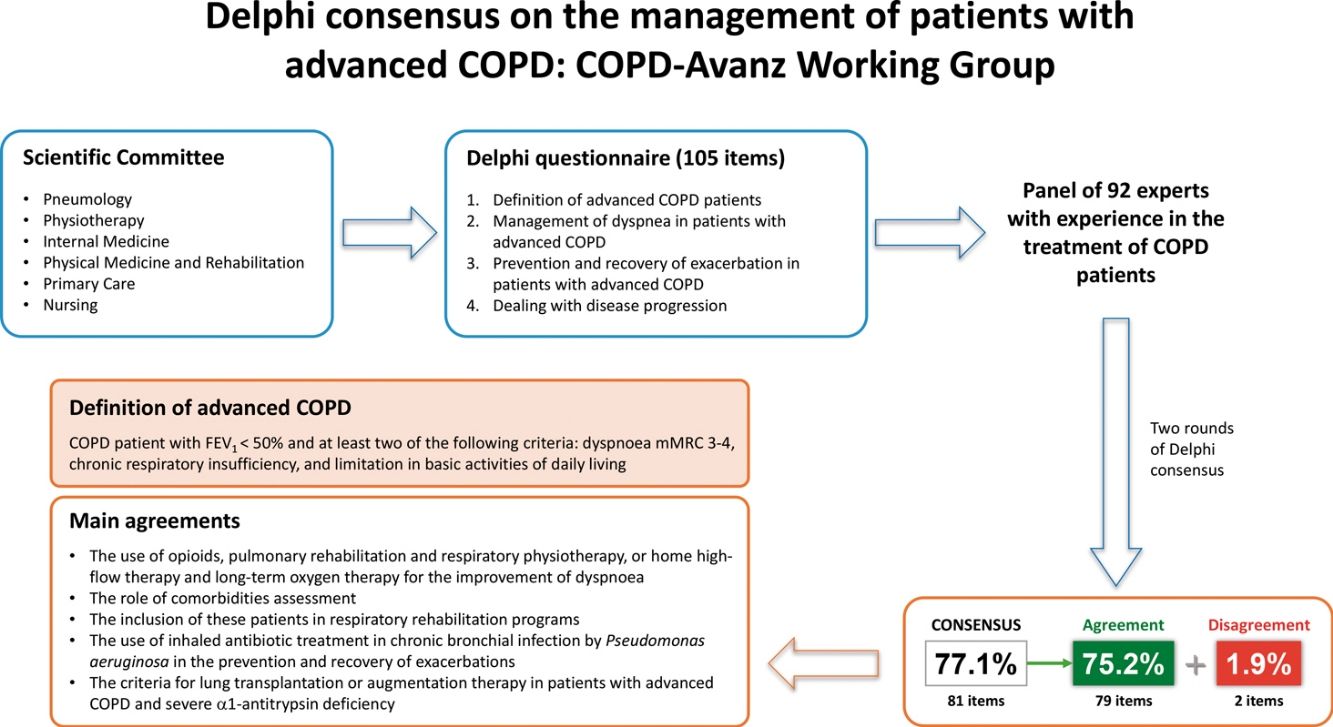

Material and methodsA multidisciplinary committee of experts (Pneumology, Physiotherapy, Internal Medicine, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Primary Care, and Nursing) developed a 105-item questionnaire to be agreed by a panel of experts grouped into the following topics: (1) Definition of advanced COPD patients; (2) Management of dyspnoea in patients with advanced COPD; (3) Prevention and recovery of exacerbation in patients with advanced COPD; and (4) Dealing with disease progression.

ResultsAfter two rounds, consensus was reached on 77.1% of the items. The definition proposed for advanced COPD and agreed by 91.5% of the panellists stated: “COPD patient with FEV1<50% and at least two of the following criteria: dyspnoea mMRC 3–4, chronic respiratory insufficiency, and limitation in basic activities of daily living”. Other relevant agreements were: the use of opioids, pulmonary rehabilitation and respiratory physiotherapy, or home high-flow therapy and long-term oxygen therapy for the improvement of dyspnoea; the role of comorbidities assessment; the inclusion of these patients in respiratory rehabilitation programmes; the use of inhaled antibiotic treatment in chronic bronchial infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the prevention and recovery of exacerbations; and the criteria for lung transplantation or augmentation therapy in patients with advanced COPD and severe α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

ConclusionsIn this document, a broad panel of experts reached a high degree of consensus on the definition of advanced COPD as well as on its approach. The information provided by this consensus is intended to assist the clinician in the identification of these patients as well as to provide guidance on their management.

Alcanzar un consenso multidisciplinar sobre el manejo de los pacientes con EPOC avanzada mediante la metodología Delphi.

Material y métodosUn comité multidisciplinar de expertos (Neumología, Fisioterapia, Medicina Interna, Medicina Física y Rehabilitación, Atención Primaria y Enfermería) elaboró un cuestionario de 105 aseveraciones para ser consensuado por un panel de expertos agrupados en los siguientes temas: 1) Definición de pacientes con EPOC avanzada; 2) Manejo de la disnea en pacientes con EPOC avanzada; 3) Prevención y recuperación de la exacerbación en pacientes con EPOC avanzada; y 4) Afrontamiento de la progresión de la enfermedad.

ResultadosTras dos rondas, se alcanzó un consenso en el 77,1% de las aseveraciones. La definición propuesta para EPOC avanzada y consensuada por el 91,5% de los panelistas establecía: “Paciente con EPOC con FEV1<50% y al menos dos de los siguientes criterios: disnea mMRC 3-4, insuficiencia respiratoria crónica y limitación en las actividades básicas de la vida diaria”. Otros acuerdos relevantes fueron: el uso de opioides, rehabilitación pulmonar y fisioterapia respiratoria, o terapia de alto flujo domiciliario y oxigenoterapia a largo plazo para la mejoría de la disnea; el papel de la evaluación de las comorbilidades; la inclusión de estos pacientes en programas de rehabilitación respiratoria; el uso de tratamiento antibiótico inhalado en la infección bronquial crónica por Pseudomonas aeruginosa en la prevención y recuperación de las exacerbaciones; y los criterios de trasplante pulmonar o terapia de aumento en pacientes con EPOC avanzada y déficit grave de α1-antitripsina.

ConclusionesEn este documento, un amplio panel de expertos alcanzó un alto grado de consenso en lo que respecta a la definición de EPOC avanzada, así como en su abordaje. La información proporcionada por este consenso pretende ayudar al clínico en la identificación de estos pacientes, así como orientar sobre su manejo.

.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive and debilitating respiratory condition that significantly impacts patients’ quality of life, particularly in its advanced stages. The management of advanced COPD remains a clinical challenge due to limited solid evidence on the effectiveness of many therapeutic strategies in this group of patients.1–6 A personalized and multidisciplinary approach is essential to optimize outcomes in these patients.

To address this issue, we have designed this study, which aims to reach a consensus on the main key points in the management of patients with advanced COPD, given the conceptual discrepancies and limited evidence in this field. To this end, a survey was conducted following the Delphi methodology, a method that aims to advance towards a consensus among a group of experts on complex or controversial issues that have insufficient, weak or controversial evidence.7 In parallel to the Delphi, an additional survey was conducted to reach a definition of advanced COPD.

Material and methodsStudy designThe study was designed using a Delphi method with the aim of reaching a consensus on topics related to the management of patients with advanced COPD. The Delphi method is a structured communication technique that allows a group of experts to explore and unify opinions on a given complex or controversial topic for which there is insufficient evidence.8,9

The study was carried out in several phases: (1) Establishment of a scientific committee of experts; (2) Review and discuss of the most recent scientific evidence on the topic; (3) Drafting of a Delphi questionnaire on those topics considered most controversial or relevant; (4) Two-round Delphi consensus to know the opinion of a panel of experts on the items proposed in the questionnaire; and (5) Compilation, analysis, and discussion of the results of the Delphi consensus to draw up conclusions.

In parallel to the Delphi consensus, a survey was carried out to choose the most appropriate definition of advanced COPD. Initially, 4 definitions were proposed. The two with the highest number of votes were submitted to a second round to select the one with the highest number of votes.

ParticipantsThe study involved a scientific committee composed of 3 coordinators and 15 experts (from the specialties of Pneumology, Physiotherapy, Internal Medicine, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Primary Care, and Nursing), who were in charge of reviewing the most recent published evidence and drafting the Delphi questionnaire; and a panel of 92 experts who showed their degree of agreement or disagreement with the items proposed in the questionnaire. The panel of experts was selected by the scientific committee for their recognized experience in the treatment of COPD patients, ensuring adequate territorial representation from all regions of Spain.

Delphi questionnaireThe questionnaire consisted of 105 items grouped into the following topics: (1) Definition of advanced COPD patients; (2) Management of dyspnoea in patients with advanced COPD; (3) Prevention and recovery of exacerbation in patients with advanced COPD; and (4) Dealing with disease progression.

To respond to the items, a unique 9 point ordinal Likert-type scale was proposed according to the model developed by UCLA-RAND Corporation (minimum 1, full disagreement; and maximum 9, full agreement).9 This scale was structured in three groups according to the level of agreement–disagreement of the item: from 1 to 3, interpreted as rejection or disagreement; from 4 to 6, interpreted as no agreement or disagreement; and from 7 to 9, interpreted as expression of agreement or support.

Phases of the Delphi consensusFollowing the Delphi methodology procedure, the questionnaire was sent to the panel of experts so they could respond by showing their degree of agreement with each item. In the first round, the panellists responded to the questionnaire online and were offered the possibility of adding their opinion in open text. Non-consensus statements were sent back to the panellists to be assessed in a second round. The project was closed with a meeting of the scientific committee to discuss and analyze the results.

Analysis and interpretation of the resultsThe median and the interquartile range of the scores obtained for each item were used to analyze the type of consensus reached on each one. The consensus was reached when two-thirds or more of the respondents (≥66.7%) scored within the 3-point range (1–3 or 7–9) containing the median. The type of consensus achieved on each item was determined by the median value of the score. There was agreement if the median was ≥7, and there was disagreement if the median was ≤3. When the median score was located between a 4–6 range, the items were uncertain.

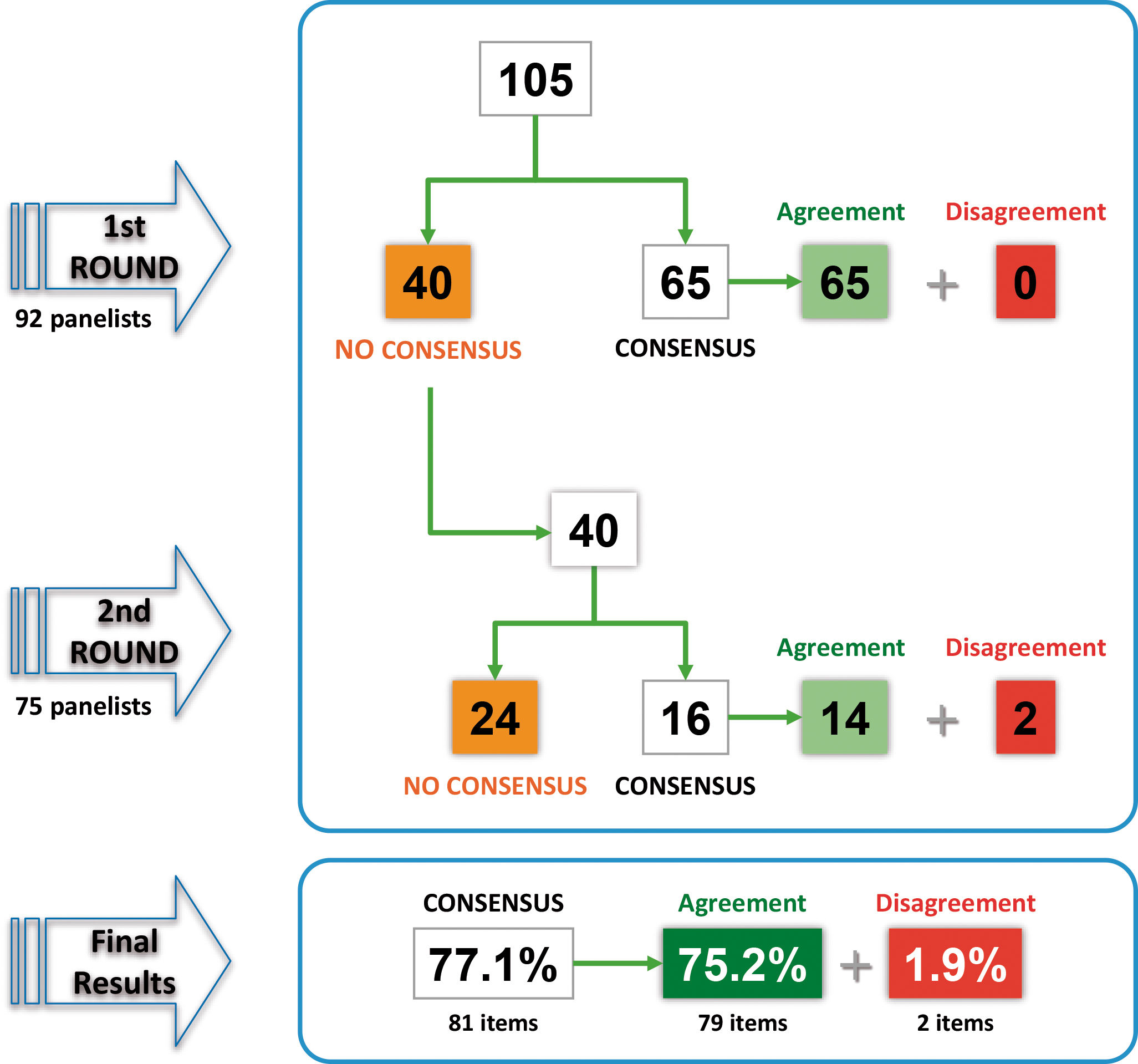

ResultsOf the 92 panellists initially consulted, 75 completed the two rounds of the Delphi consensus (Supplementary material). In the first round, consensus was reached on 65 of the 105 items, all of which were in agreement. The remaining 40 items were returned for reconsideration in the second round, and consensus was reached on 16 of them: 14 in agreement and 2 in disagreement. After two rounds, consensus was reached on 81 items (77.1%): 79 in agreement (75.2%) and 2 in disagreement (1.9%). Fig. 1 shows the results of the two rounds and Tables 1–4 show the overall results of all the proposed items.

Definition of advanced COPD patients.

BODE: Body-mass index, airway Obstruction, Dyspnoea, Exercise; CAT: COPD Assessment Test; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; DLCO: Diffusing Capacity of the Lungs for Carbon Monoxide; FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1Second; IQR: interquartile range; mMRC: Modified Medical Research Council.

Green: consensus in agreement; Red: consensus in disagreement; White: without consensus.

Management of dyspnoea in patients with advanced COPD.

BODE: Body-mass index, airway Obstruction, Dyspnoea, Exercise; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; IQR: Interquartile Range; LABA: Long-Acting Beta2-Agonist; NIMV: Non-invasive Mechanical Ventilation.

Green: consensus in agreement; Red: consensus in disagreement; White: without consensus.

Prevention and recovery of exacerbations in patients with advanced COPD.

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ICS: Inhaled Corticosteroids; IQR: Interquartile Range; IU: International Units; LABA: Long-Acting Beta2-Agonist; LAMA: Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonist.

Green: consensus in agreement; Red: consensus in disagreement; White: without consensus.

Of the 11 items proposed about the criteria for defining a patient with advanced COPD, 7 were agreed with a high degree of agreement.

The panellists endorsed that this definition should include severe airflow obstruction (Forced Expiratory Volume in 1Second [FEV1]<50%) (76.1% agreement), significant clinical impact (COPD Assessment Test [CAT]>30) (71.7% agreement), dyspnoea grade 3–4 according to Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) (94.6% agreement), significant limitation in performing daily activities (89.1% agreement), and the number and severity of comorbidities (70.1% agreement), but not necessarily the existence of exacerbations (did not reach consensus). Likewise, the usefulness of validated multidimensional indices for the determination of advanced COPD was also highlighted.

The survey on the definition of advanced COPD proposed four options, whose degree of agreement among the panellists is shown in Table 5. The two definitions with the highest degree of agreement were selected to be re-evaluated in a second round. As the two definitions selected obtained a very similar percentage of agreement and were surveyed before the Delphi consensus, the expert committee proposed modifying the criteria included in the definition to adapt them according to the agreements reached in this consensus (Table 5). Thus, the number of exacerbations (a criterion not agreed in the Delphi) was eliminated from the definition and replaced by limitation in basic activities of daily living.10 The proposed new definition for advanced COPD stated: “COPD patient with FEV1<50% and at least two of the following criteria: dyspnoea mMRC 3–4, chronic respiratory insufficiency, and limitation in basic activities of daily living (dressing, showering, etc.)”. This definition was sent back to the panellists to show their degree of agreement on a scale from 1 (complete disagreement) to 5 (complete agreement), obtaining an average rating of 4.3. A total of 91.5% of the panellists agreed with this definition (sum of respondents with scores of 4 and 5).

Survey on the definition of advanced COPD.

| Initial definitions | Agreement | |

|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |

| COPD patient with BODE>6 | 22.9% | – |

| COPD patient with FEV1<50% and all the following criteria: dyspnoea mMRC 3–4, chronic respiratory insufficiency, and ≥1 severe exacerbations in the last year. | 54.8% | – |

| COPD patient with FEV1<50% and at least two of the following criteria: dyspnoea mMRC 3–4, chronic respiratory insufficiency, and ≥1 severe exacerbations in the last year. | 62.6% | 50.7% |

| COPD patient who meets 2 major criteria or major and 2 minor criteriaa | 59.8% | 49.4% |

| Definition with the highest degree of agreement adjusted according to Delphi consensus results | Agreement |

|---|---|

| Round 3 | |

| COPD patient with FEV1<50% and at least two of the following criteria: dyspnoea mMRC 3–4, chronic respiratory insufficiency, and limitation in basic activities of daily living (dressing, showering, etc.). | 91.5% |

BODE: Body-mass index, airway Obstruction, Dyspnoea, Exercise; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1Second; mMRC: Modified Medical Research Council.

Of the 37 items proposed about the management of dyspnoea in patients with advanced COPD, 25 were agreed and 1 was disagreed by the panellists.

They agreed that the initiation of palliative care for dyspnoea in these patients should be decided according to multidimensional indices of COPD severity, such as the BODE (67.5% agreement). On the treatment of dyspnoea, they agreed on the use of rapid-release opioid formulations, initially at low doses until the appropriate dose is reached (77.2% agreement), and in case acute episodes of severe dyspnoea do not respond to bronchodilators, short-acting opioids can be used on demand (73.9% agreement).

The panellists highlighted the role of pulmonary rehabilitation and respiratory physiotherapy in the benefit of patients with advanced COPD, complementing hospital rehabilitation programmes with home rehabilitation programmes (full agreement). Likewise, inspiratory muscle training was considered to improve dyspnoea (88% agreement), and the combination of the pursed-lip breathing control technique with previous medication (bronchodilators, short-acting opioids, and anxiolytics) was considered beneficial (82.6% agreement). In addition, it was agreed that a pulmonary rehabilitation programme should be carried out prior to endoscopic volume reduction (91.3% agreement), a technique that can be used as a bridge therapy until lung transplantation (68.5% agreement).

It was also agreed that home high-flow therapy and long-term oxygen therapy improve dyspnoea (71.7% and 77.2% agreement respectively). Although it was agreed that non-invasive mechanical ventilation improves exercise capacity and is useful in rehabilitation (72.7% and 76.1% agreement respectively), there was no consensus on its usefulness in relieving dyspnoea.

The panellists agreed that patients with advanced COPD are at increased risk for cardiovascular events (94.6% agreement), and that it is necessary to actively seek and treat heart failure to improve dyspnoea in these patients (98.9% agreement), but they disagreed that long-acting β2-agonist (LABAs) therapy increases the incidence of cardiovascular events in these patients (74% disagreement). Cardio-selective β-blockers were considered safe in patients with advanced COPD (89.1% agreement).

Prevention and recovery of exacerbations in patients with advanced COPDOf the 31 items proposed about the prevention and recovery from exacerbations, 28 were agreed with a high degree of agreement.

Firstly, the role of pulmonary rehabilitation and respiratory physiotherapy (hospital/home) was highlighted by the panellists as reducing the risk of hospital admissions or readmissions and the recurrence of exacerbations, especially when used early after an exacerbation (> 91% agreement). Peripheral muscle strengthening and ventilatory control techniques were also considered beneficial in improving dyspnoea and quality of life (92.2% and 91.3% agreement respectively).

Secondly, the panellists considered that the presence of two or more comorbidities in patients with advanced COPD is more frequent than in other COPD patients (93.5% agreement) and have a negative impact on symptoms and are associated with an increased risk of exacerbations (88% agreement).

Thirdly, on the follow-up of exacerbations, it was agreed to include patients in a case management programme when they are admitted for an exacerbation (88.1% agreement), and a consultation with healthcare professional should be made within 72–96h after discharge from hospital (77.2% agreement). There was full agreement that after hospitalization for decompensation these patients have increased frailty which is related to an increased risk of readmission and functional dependency.

Fourthly, regarding chronic infections in these patients, it is interesting to note that while there is agreement that chronic bronchial infection by pathogens other than Pseudomonas aeruginosa lead to an unfavourable clinical course (76.1% agreement), there was no consensus on their treatment.

Finally, it was noteworthy the consensus obtained on the use of vitamin D supplementation in the context of advanced COPD with low vitamin D levels to reduce the number of moderate and severe exacerbations (71.4% agreement) and the use of dupilumab to reduce the number of moderate and severe exacerbations in patients with advanced eosinophilic COPD with frequent exacerbations despite receiving triple therapy (long-acting muscarinic antagonist [LAMA]/LABA/inhaled corticoids [ICS]) (72.7% agreement).

Dealing with disease progressionOf the 16 items that addresses the dealing with disease progression, 19 were agreed and 1 was disagreed by the panellists.

One of the agreements was the indication for lung transplantation in patients with advanced COPD with a BODE value>6 if there are no contraindications (76.6% agreement). In addition, patients with advanced COPD referred for lung transplantation should be first evaluated for volume reduction, preferably endoscopically (68.5% agreement). It was also agreed that augmentation therapy is indicated in patients with advanced COPD and severe α-1-antitrypsin deficiency, especially with evident progression (85.9% agreement). The panellists were against withdrawal of augmentation therapy in patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency and advanced COPD (74% disagreement).

For better symptom control, it was agreed that palliative care should be performed progressively without waiting until life expectancy is considered in the short term (92.4% agreement). In patients with advanced COPD, palliative care at home should be incorporated in a staggered manner during the course of the disease (96.7% agreement). In addition, the panellists emphasized the role of nurses and patient self-care training to improve quality of life (>94% agreement).

DiscussionIn general, the opinion of the participants in this Delphi consensus on the management of advanced COPD is broadly uniform, as suggested by the high degree of consensus reached on almost 78% of the proposed items, of which only two were disagreed (1.9%).

The advanced stage of the disease is characterized by a high frequency of symptoms, loss of functionality, and an increasing number of exacerbations, leading to a significant deterioration in quality of life, high consumption of health resources, and reduced survival. To date, there is no consensus definition of advanced COPD and the available evidence is very heterogeneous due to the lack of a universal definition.11 Given that the impact of the disease is multidimensional, it is possible that the definition should include several components. Klimathianaki et al. and Viegi et al. defined the end-stage COPD according to the clinical features of the disease (severely limited and declining performance status, advanced age, presence of multiple comorbidities, and severe systemic manifestations/complications of COPD).12,13 Philip et al. defined advanced COPD if the patient had any of the following characteristics: FEV1<30%, a high degree of dyspnoea, a poor quality of life according to the CAT questionnaire or frequent use of health care resources.14 However, defining this stage of the disease exclusively with a single criterion can be misleading since aspects such as the degree of dyspnoea, the deterioration of quality of life or even the need for hospital admission may be dependent on aspects unrelated to the disease (e.g. comorbidities, social situation, architectural barriers or distance to hospital/emergency services, among others). In our survey, panellists selected severe airflow obstruction, the presence of chronic respiratory failure and functional limitation as criteria for defining advanced COPD, whereas the presence of comorbidities and exacerbations were excluded. It was concluded that the definition of advanced COPD should mandatorily include the degree of airway obstruction (FEV1<50%) in order to avoid labelling as advanced COPD those patients who suffer from a milder airflow obstruction, but with high burden of comorbidities which would be responsible for the loss of functionality. The lack of consensus on considering exacerbations in the definition may be due to the absence of a specific concept of exacerbations according to the panellists. Although the presence of exacerbations has been shown to be a prognostic factor in COPD patients, the fact that their identification and treatment depends on multiple aspects (comorbidity, the patient's baseline situation and of their ability to communicate it, social situation or the knowledge of the attending physician, among others) with a pattern of appearance that is usually irregular over time, makes its inclusion in the definition not practical. On the other hand, in order for the definition of advanced COPD to have a transversal applicability, it was decided to use aspects easily recognizable by both levels of care (primary care and hospital care) being excluded the performance of the 6-min walk test or the determination of diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Although the panellists agreed the usefulness of validated multidimensional indices for the determination of advanced COPD, it is important to keep in mind that these types of scales (e.g., BODE index) provide prognostic indices but not an assessment of patient status. It is possible that the panellists interpreted that the definition of advanced COPD should include several factors and not just one and that, therefore, it should be clarified that instead of speaking of “multidimensional scales” it should be referred to as “multifactorial assessment”.

Dyspnoea is the most prevalent and distressing symptom in patients with advanced COPD and is associated with higher healthcare resource utilization and costs.6 There was a broad consensus among the proposed items, highlighting the use of rapid-release opioid formulations or on demand short-acting opioids in case acute episodes of severe dyspnoea do not respond to bronchodilators. Palliative approaches to these symptoms are effective and their use should not be restricted to end of life situations. Opiates can relieve breathlessness, oxygen may offer some benefit even if the patient is not hypoxaemic (peripheral capillary oxygen saturation>92%) and a multidisciplinary integrated palliative and respiratory care approach to relieve dyspnoea can be of value.15 However, it is difficult to identify when the patient should be referred for palliative care. Referral too early may worsen the anxiety or depression and on the other hand, referral too late may limit the effectiveness of the treatment. For all these reasons, the correct training of healthcare workers involved in respiratory pathology is necessary. There was no consensus on some aspects, such as who should initiate palliative care for dyspnoea reflecting that the management of advanced COPD patients involves a multidisciplinary panel of professionals. Furthermore, the panellists highlighted the importance of the benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation and respiratory physiotherapy as well as the use of home high-flow therapy or long-term oxygen therapy for the relief of dyspnoea. Regarding the latter, it has been striking that, without clear evidence to support its prescription,16,17 there was consensus on the use of long-term oxygen therapy in patients with advanced COPD with moderate hypoxaemia at rest and exercise-induced desaturation, depending its continuation on patient's clinical improvement. With regard to home high-flow therapy, this therapy has a beneficial effect on the pathophysiological mechanisms associated with COPD (stable prescribed fraction of inspired oxygen [FiO2], improved secretion clearance, reduced inspiratory effort and reduced air trapping), and is safe in both the short and long term, even in patients with hypercapnia.18 Taking into account the evidence available to date, the high-flow therapy could be an alternative for patients with high dyspnoea degree19 and very high risk of exacerbations,18 where patients with advanced COPD would be included. On the other side, endoscopic lung volume reduction is a minimally invasive procedure that has been demonstrated to improve dyspnoea in patients with severe hyperinflation, being the advanced COPD patient a potential candidate. Patients considered for this intervention must be clinically stable and with a maximized treatment to safely undergo the procedure including smoking cessation. Smoking cessation has shown significant benefits to COPD patients, especially in improving specific key indicators of lung function (FEV1% predicted), alleviating symptoms, improving exercise tolerance and may reduce mortality.20 For these reasons, smoking cessation should be a priority for these patients. Given their complexity, it would be advisable to include them in a structured programme for this purpose. Pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to improve exercise capacity in those subjects selected for endoscopic volume reduction,21 an aspect that is reflected in the opinion of the panellists. Apart from this procedure, the importance of including these patients in a pulmonary rehabilitation programme22 is evident from the opinion of the experts. Depression is common in patients with COPD and should be actively sought and treated. Data on the best therapeutic approach are lacking. Panellists did not reach consensus on whether treatment of depression in these patients should be different from that used in the general population.23

The panellists also showed a high degree of agreement on aspects of the prevention and recovery of exacerbations. The only notable lack of consensus was the treatment of chronic bronchial infections in these circumstances. Although the panellists showed broad agreement that infections caused by pathogens other than P. aeruginosa also lead to an unfavourable clinical course, there was no consensus about their treatment. This contradiction may be due to the limited evidence on the results of treatment of these infections in patients with COPD.

Finally, there was also broad support for the items dealing with disease progression in patients with advanced COPD, highlighting the criteria for the indication of lung transplantation or the indication of augmentation therapy with α1-antitrypsin in patients with advanced COPD and severe α1-antitrypsin deficiency. There was no consensus on its use in cases of intermediate α1-antitrypsin deficiency, although it is clearly not recommended in guidelines.24 In addition, there was consensus against withdrawing augmentation in advanced patients. The panel valued more the existing evidence of increasing survival in patients treated with augmentation therapy compared to the lack of evidence of reduction in rate of decline of FEV1 in patients with very severe COPD.25 Some of these results underscore the variability in prescription of augmentation despite the existing guidelines.26,27

The limitations of this study are those inherent to the Delphi methodology (e.g. the results depend on the accuracy of the questions, the length of sentences must be carefully evaluated, participant bias due subjective opinions or personal experience, among others). The study focused on the opinions of experts specialized in the management of COPD and may not be representative of other physicians not specialized in this disease. Further, the result obtained from this study has a temporal validity as it may change over time, and participant views were not unanimous on all questions. As a result, these findings should be interpreted rationally, and recommendations need to be further complemented to clarify the areas of uncertainty detected in the results. On the other hand, a point dedicated to raising in advance and leaving in a document of advance directives the decisions at the end of life, fundamentally regarding ventilatory support in acute or stable phase, has not been included, which could be interesting, as is already done with other progressive diseases.

One of the main strengths of this study is the participation of a large multidisciplinary panel of experts with extensive clinical experience with representation from the areas of pneumonology, primary care, internal medicine, rehabilitation and nursing. We believe that the high number of members, the high degree of participation and its territorial representativeness are elements that add great value to the document and confers great validity to its results. The sponsor was not involved in the development of the study, so a possible influence on the consensus has been minimized.

ConclusionThis document addresses, using a consensus methodology, various uncertainties or controversies affecting the management of the patient with advanced COPD. Respondents agreed on 77.1% of the proposed statements. Some of these are of interest for their innovative nature, including the definition of “advanced COPD” or providing guidance on the management of these patients which are generally not included in clinical practice guidelines.

FundingThis research was supported by SEPAR (Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica) COPD working group.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors were involved in the conception and design of the work; acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of interestJMFG has received honoraria for speaking engagements and funding for conference attendance from Laboratories Esteve, MundiPharma, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ferrer, Menarini, Rovi, GSK, Chiesi, Novartis, and Gebro Pharma.

JMD is part of the Editorial board of Open Respiratory Archives and declare that he has remained outside the evaluation and decision-making process in relation to this article. On the other hand, he has received grants and honoraria from AstraZeneca, BIAL, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, FAES, Gebro, GSK, Janssen, Menarini, Novartis, Sanofi, Roche, Teva, Pfizer, and Zambón.

BAN reports grants and personal fees from GSK; grants, personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca; personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim; personal fees and non-financial support from Chiesi; grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Laboratorios Menarini; personal fees from Bial, Zambon, MSD, and Sanofi.

PAM has received grants and honoraria from Chiesi, AstraZeneca, and GSK.

MBAO has received grants and honoraria from Chiesi, AstraZeneca, and GSK.

ABC has no conflict of interests.

MB is part of the Editorial board of Open Respiratory Archives and declare that she has remained outside the evaluation and decision-making process in relation to this article. On the other hand, she has received speaker fees from Grifols, Menarini, CSL Behring, GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi; and consulting fees from GSK, Novartis, Bial, CSL Behring, Chiesi, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

RCG has received grants and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Pfizer, and Aflofarm.

ECV is a consultant for Pulmonx.

PCR has received honoraria for lectures and scientific advice in the last 3 years from Janssen, Menarini, Vivisol; and for congress attendance from Boehringer Ingelheim, Menarini, and Vivisol.

AFV has received fees in the last 3 years for providing lectures, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing publications for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Grifols, and GSK.

RG has received speaking or advisory fees, or economic aid to attend congresses from AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, FAES, Chiesi, Mundipharma, Menarini, TEVA, Grifols, Ferrer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Rovi, and Gebro.

MIP has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GSK, and Gilead.

JLLC has received fees in the last 3 years for providing lectures, scientific advice, and participation in clinical studies or writing publications from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer, Chiesi, CSL Behring, FAES, Gebro, Grifols, GSK, Menarini, and Zambon.

JMP has received honoraria in the last 3 years for conferences, scientific advice and participation in research from AstraZeneca, Gerencia Asistencial de Atención Primaria, GSK, Menarini, Pfizer, SEPAR, semFYC, and Zambon.

DRC has received honoraria for providing lectures, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies, or writing publications from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, FAES, Gebro, Grifols, GSK, Insmed, Menarini, Praxis, TEVA, and Zambon.

JSC has received fees for academic lectures and teaching activities from Philips respironics, Resmed, Chiesi and Menarini; and is a board member for respiratory care related activities for ResMed and Philips.

MM has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, Menarini, Kamada, Takeda, Zambon, CSL Behring, Specialty Therapeutics, Janssen, Grifols, and Novartis; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Atriva Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, BEAM Therapeutics, BridgeBio, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, CSL Behring, Ferrer, Inhbrix, Menarini, Mereo Biopharma, Spin Therapeutics, Specialty Therapeutics, Palobiofarma SL, Takeda, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi/Regeneron, Zambon, Zentiva, and Grifols; and research grants from Grifols.

The authors would like to thank Fernando Sánchez Barbero PhD and Luzán 5 Health Consulting for their help in the preparation of the manuscript.

On behalf of the COPD-Avanz Working Group (panel of experts participating in the Delphi consensus shown in Appendix BSupplementary material).