Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a respiratory pathology with high prevalence, morbidity and mortality. The Spanish COPD guideline (GesEPOC) recommends individualizing treatment according to phenotypes. The phenotype classification was updated in 2021. This study aimed to determine the survival of patients by this new classification and compare the predictive capacity of mortality compared to the previous version.

MethodsThis observational study of COPD patients involved prospective follow-up for 6 years. Demographic and clinical data were collected at the beginning and evolutionary data at the end of the study. Patients were classified according to GesEPOC 2017 and GesEPOC 2021. Univariate survival analysis and multivariate analysis identified mortality risk factors.

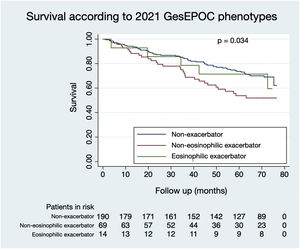

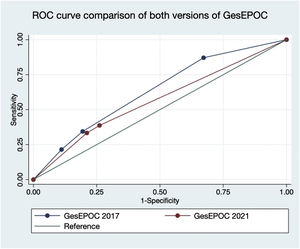

ResultsOf the 273 patients, 243 (89.0%) were male. Ninety-three patients (34.1%) died during follow-up. Regarding phenotypes, 190 patients (69.6%) were non-exacerbators, 69 (25.3%) belonged to the non-eosinophilic exacerbator phenotype and 14 (5.1%) were of the eosinophilic exacerbator phenotype. Compared with non-exacerbator patients, those with the non-eosinophilic exacerbator phenotype had lower survival (p=0.009). Risk factors independently associated with mortality were older age (p<0.001), non-eosinophilic exacerbator phenotype (p=0.017) and a high Charlson index score (p<0.001). The new classification presented a worse ability to predict mortality than the previous version (area under the curve 0.632 vs 0.566, p=0.018).

ConclusionPatients with the non-eosinophilic exacerbator phenotype had worse prognoses. This phenotype, advanced age and high comorbidity were mortality risk factors. The GesEPOC 2021 classification predicts mortality worse than the 2017 version. These data must be considered for more individualized management of COPD patients.

La enfermedad obstructiva crónica (EPOC) es una patología respiratoria con elevada prevalencia y alta morbimortalidad. La guía española de la EPOC (GesEPOC) recomienda individualizar el tratamiento según fenotipos. En su última actualización en 2021, se ha actualizado la clasificación de fenotipos. Se realiza este estudio para conocer la supervivencia de los pacientes sobre esta nueva clasificación y para comparar la capacidad predictiva de mortalidad con respecto a la versión previa.

MétodosEstudio observacional de pacientes con EPOC con un seguimiento prospectivo durante 6 años. Se recogieron datos demográficos y clínicos al inicio y datos evolutivos al final del estudio. Se clasificó a los pacientes según GesEPOC 2017 y GesEPOC 2021. Se realizó un análisis univariante de supervivencia y un análisis multivariante para identificar factores de riesgo de mortalidad.

ResultadosDel los 273 pacientes, 243 (89,0%) eran varones. Fallecieron 93 sujetos (34,1%) durante el seguimiento. En cuanto a los fenotipos, 190 pacientes (69,6%) eran no agudizadores, 69 (25,3%) pertenecían al fenotipo agudizador no eosinofílico, y 14 (5,1%) eran del fenotipo agudizador eosinofílico. Comparando con los enfermos no agudizadores, los del fenotipo agudizador no eosinofílico tuvieron una menor supervivencia (p = 0,009). Los factores de riesgo independientemente asociados a la mortalidad fueron la edad avanzada (p < 0,001), el fenotipo agudizador no eosinofílico (p = 0,017) y una puntuación elevada en el índice de Charlson (p < 0,001). La nueva clasificación presentó una peor capacidad para predecir mortalidad en comparación con la versión previa (área bajo curva 0,632 vs 0,566, p = 0,018).

ConclusiónLos pacientes del fenotipo agudizador no eosinofílico tenían peor pronóstico. Este fenotipo, junto con la edad avanzada y la elevada comorbilidad, fueron factores de riesgo de mortalidad. La clasificación GesEPOC 2021 predice peor la mortalidad con respecto a la versión de 2017. Es importante tener estos datos en cuenta para ofrecer un manejo más individualizado a los pacientes con EPOC.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a highly prevalent respiratory pathology that entails considerable healthcare costs.1 Although it has well-defined diagnostic criteria, the individual clinical characteristics differ from one patient to another.2 National3 and international4 practice guidelines exist for the management of this disease. Of these, the Spanish COPD guideline (GesEPOC)3 was the first to propose individualized patient management using a phenotype classification.

Phenotypes are defined as those characteristics of the disease that, individually or in combination with others, allow studying the differences between patients with COPD concerning different parameters with clinical significance.5 The 2017 version of GesEPOC classified patients in the following way3: if a patient had an postbronchodilator FEV1 of ≥50% predicted, and dyspnoea of grade 0–1 according to the mMRC scale with or without an exacerbation in the last year (without admission), they were considered low risk; patients who did not meet any of these criteria were high risk. The latter were classified into four different phenotypes: non-exacerbator, exacerbator with emphysema, exacerbator with chronic bronchitis, and asthma–COPD overlap (ACO). A patient was considered a non-exacerbator if in the previous year they had presented one or no episodes of moderate exacerbation. They were classified as an exacerbator with emphysema if they had experienced at least two exacerbations classified as moderate or severe per year, requiring at least treatment with systemic corticosteroids and/or antibiotics together with the clinical, radiological or functional diagnosis of emphysema. However, if it had been characterized by the presence of cough accompanied by expectoration maintained for a minimum of three months a year in two consecutive years, they were classified as an exacerbator with chronic bronchitis. If the patient presented diagnostic criteria for asthma and/or asthmatic characteristics such as an increase in FEV1 >400mL and 15% and/or peripheral blood eosinophilia >300cells/μL, they were considered to have an asthma–COPD overlap.

In its last update in 2021, GesEPOC redefined the classification by phenotypes.6 The concept of low-risk or high-risk patients has been maintained, with three phenotypes established for the latter: non-exacerbator, non-eosinophilic exacerbator and eosinophilic exacerbator. A patient is considered a non-exacerbator if they have presented at most one exacerbation in the previous year without requiring hospital care. A patient is classified as a non-eosinophilic exacerbator if they have had two or more outpatient exacerbations in the previous year, or one or more serious exacerbations that required hospital care, together with <300eosinophils/mm3 in peripheral blood. A patient belongs to the eosinophilic exacerbator phenotype if, in addition to meeting the criteria for the exacerbator phenotype, they have a count of >300eosinophils/mm3 in the stable phase.

Due to the update in the phenotype classification, the present study aimed to analyse the differences in the survival of patients with different COPD phenotypes based on the current 2021 classification, identify risk factors independently associated with mortality and compare the prognostic capacity of the current classification compared to the previous 2017 version.

Patients and methodsStudy design and populationThis was a retrospective sub-study of a prospective and non-interventional cohort of COPD patients in a Madrid hospital. Patients were included if they were older than 40 years with a smoking history, active or not, with a pack-year index greater than 10, and with an established diagnosis of COPD according to the definition of the Global Organization of Lung Disease, and who underwent spirometry requested by any speciality and for any reason during January to June 2011. Excluded were patients who had an FEV1 of >70% of the theoretical value, those who had respiratory pathologies other than COPD and those who were included in a clinical trial that could alter the standard management of the disease.

Collected variablesThe variables were collected in two phases. During the recruitment phase, data on the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were collected, including age, sex, smoking history, comorbidities, lung function, blood eosinophil levels, the presence of radiological abnormalities and the presence of a COPD exacerbation in the previous 12 months. A prospective follow-up of these patients was carried out until April 1, 2017. During this follow-up phase, the evolution of the patients was documented, including the presence of COPD exacerbations, the consumption of health resources and death.

COPD phenotypesThe patients were classified into the different phenotypes according to GesEPOC 2017 and GesEPOC 2021 retrospectively.

According to GesEPOC 2017, the patients were classified into the phenotypes positive bronchodilator test (PBD), non-exacerbator, exacerbator with emphysema and exacerbator with chronic bronchitis. First, patients who had a positive response in the bronchodilator test (an increase in FEV1 greater than 200mL in absolute value and an increase greater than 12% in relative value with respect to FEV1 without bronchodilation) were classified in the positive PBD phenotype. Then, the remaining patients who had no exacerbations with admission or more than one exacerbation without admission in the previous 12 months were considered non-exacerbators. Finally, the remaining patients who had dyspnoea as the predominant symptom, or who had radiographic emphysema, or who had diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) were grouped into the emphysema exacerbator phenotype, and those who had cough and expectoration for more than three months per year in the last two consecutive years were classified in the exacerbator phenotype with chronic bronchitis. Thus, the 2017 GesEPOC criteria were not followed to define the ACO phenotype (asthma–COPD overlap) because we considered that the limits of an increase in FEV1 greater than 400mL and 15% provided high specificity but insufficient sensitivity.

According to GesEPOC 2021, patients were classified into non-exacerbator, non-eosinophilic exacerbator and eosinophilic exacerbator phenotypes. First, those patients who had no exacerbation with admission or more than one exacerbation without admission in the previous year were considered non-exacerbators. Subsequently, the remaining patients were classified into non-eosinophilic exacerbator and eosinophilic exacerbator phenotypes based on whether or not they had more than 300 eosinophils per millilitre of peripheral blood.

Statistical analysisThe presence or absence of normal distribution of the variables was determined by histogram and the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests.

For descriptive statistics, quantitative variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD), and quantitative variables that did not present normal distribution were described with median and interquartile range (IQR). The qualitative variables were expressed as a frequency.

For the comparison of the variables, the quantitative variables with normal distribution were analysed by analysis of variance, whereas those quantitative variables without normal distribution were compared with the Kruskal–Wallis test. For the comparison of qualitative variables and the comparison of proportions, the Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test was used, depending on the sample size.

The survival of the patients according to phenotypes was represented with the Kaplan–Meier graph, and the univariate comparison of the probability of death according to the phenotypes was performed with the log-rank test. The ability to predict mortality according to the GesEPOC 2017 and GesEPOC 2021 phenotypes was compared with the ROC curves using the Stata's roccomp command, after converting the qualitative variable of phenotypes into a quantitative variable, the probability of death in each phenotype, using logistic regression.

For the multivariate analysis of survival adjusted for age, sex, FEV1, phenotype, active smoking, and Charlson index, Cox regression was used. The presence of proportionality of risks of the variables included in the multivariate model was verified.

For any of the comparisons made, the level of statistical significance was established at p<0.05 (two-sided).

The statistical programs used were SPSS version 26 for descriptive statistics and Stata version 15 for the rest of the analysis performed.

Ethical aspectsThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón with code HUIL-05/17. The participants signed informed consent.

ResultsA total of 273 patients were included, of whom 243 (89%) were male. The mean age was 68 years (SD 10.62), the mean weight was 75.03kg (SD 16.89), the mean height was 1.63m (SD 0.08), and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 28.05kg/m2 (SD 5.49). Regarding lung function, the mean FEV1 in absolute value was 1211.39mL (SD 416.55), and the mean FEV1 in relative value was 48.64% (SD 12.59). Regarding comorbidities, the median Charlson comorbidity index score was 2 (IQR 1–4). At the time of inclusion in the study, 92 patients (34%) were current smokers. The median prospective follow-up was 68.16 months (IQR 40.69–72.12). During this time, 93 patients (34.1%) died.

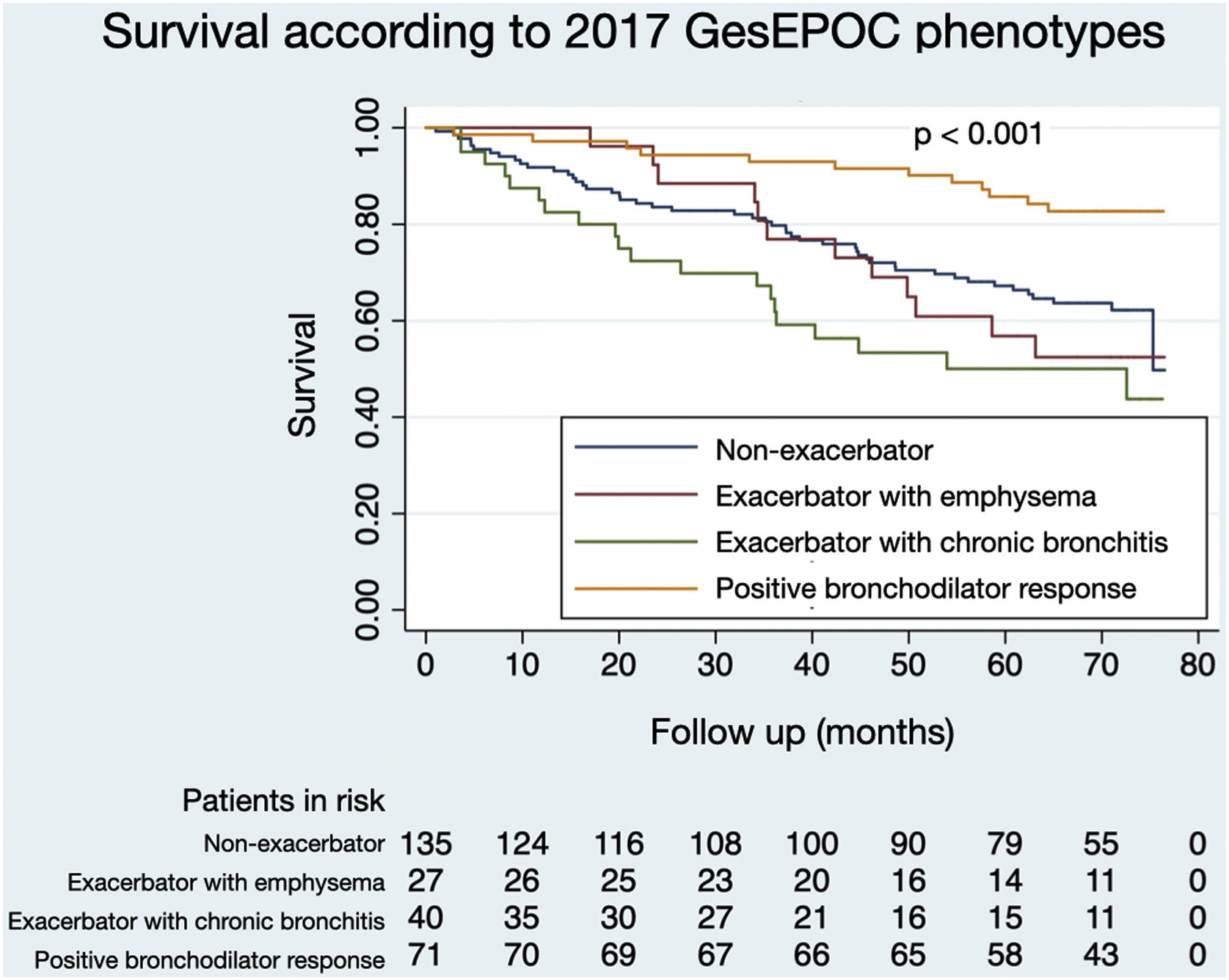

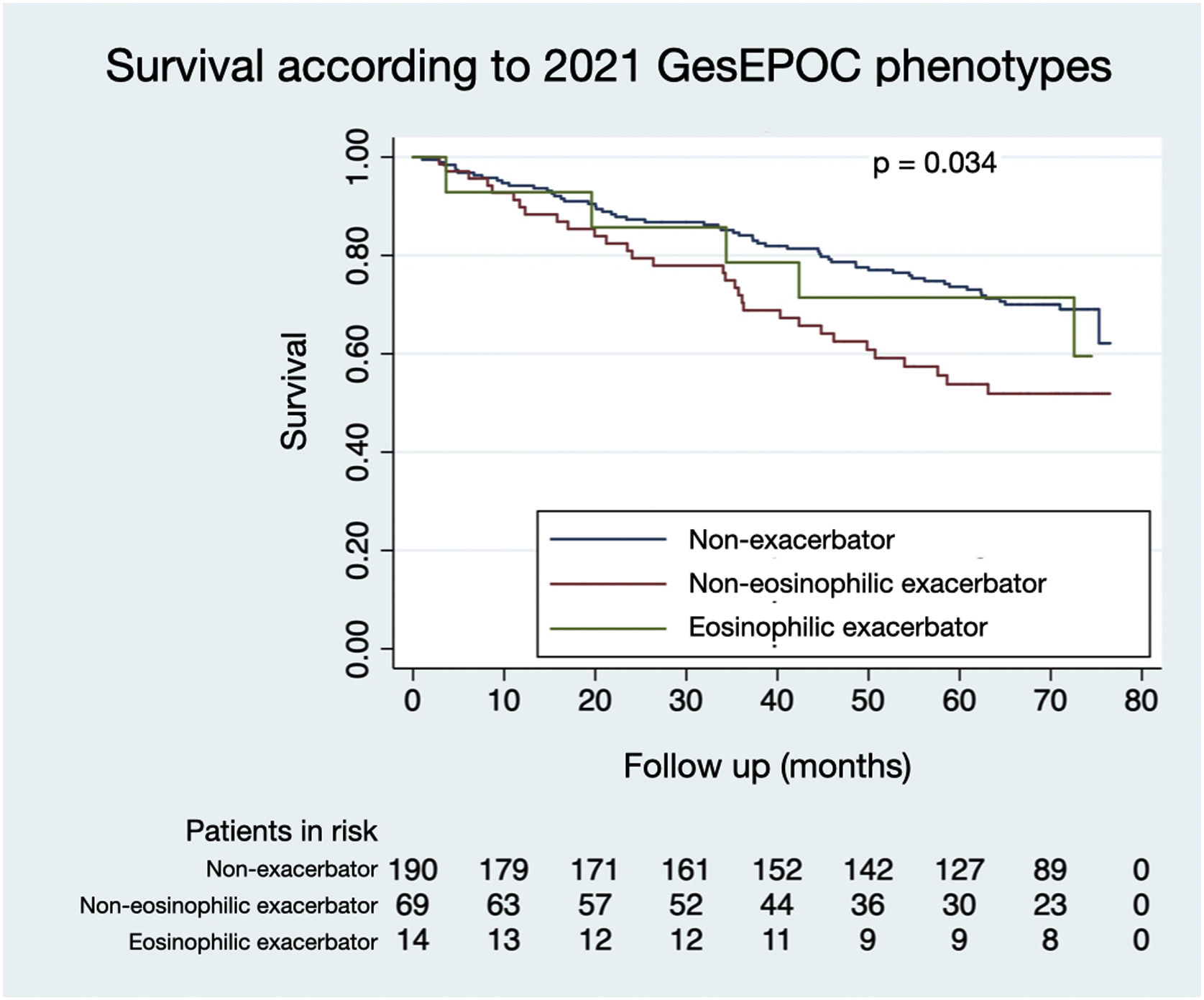

The distribution of patients by GesEPOC 2017 phenotypes was as follows: 71 (26.0%) had a positive bronchodilator response, 135 (49.5%) were non-exacerbators, 27 (9.9%) were exacerbators with emphysema and 40 (14.7%) were exacerbators with chronic bronchitis. According to GesEPOC 2021, 190 patients (69.6%) were non-exacerbators, 69 patients (25.3%) were non-eosinophilic exacerbators and 14 patients (5.1%) were eosinophilic exacerbators.

Tables 1 and 2 show the comparison of the general characteristics of the patients according to the phenotypes defined by GesEPOC 2017 and GesEPOC 2021, respectively. Classifying the patients according to GesEPOC 2017, the mean age was higher in the non-exacerbator and exacerbator phenotypes with chronic bronchitis (p<0.001), and patients with positive PBD presented less active smoking (p=0.009) and a higher lung function measured in FEV1 in absolute value (p<0.001). Based on GesEPOC 2021, non-exacerbator patients had better lung function (p=0.012).

Comparison of the general characteristics of the patients based on the phenotypes according to GesEPOC 2017.

| Variable | Phenotype GesEPOC 2017 | N/mean/median | %/SD/IQR | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n) | Non-exacerbator | 124 | 91.9 | 0.342 |

| Emphysema exacerbator | 22 | 81.5 | ||

| E. with chronic bronchitis | 34 | 85.0 | ||

| PBD positive | 63 | 88.7 | ||

| Age (years) | Non-exacerbator | 69.76 | 9.33 | 0.000 |

| Emphysema exacerbator | 67.44 | 11.29 | ||

| E. with chronic bronchitis | 70.47 | 10.09 | ||

| PBD positive | 67.99 | 10.62 | ||

| Active smoking (n) | Non-exacerbator | 99 | 73.3 | 0.009 |

| Emphysema exacerbator | 20 | 74.1 | ||

| E. with chronic bronchitis | 26 | 65.0 | ||

| PBD positive | 36 | 50.7 | ||

| Weight (kg) | Non-exacerbator | 76.04 | 17.75 | 0.130 |

| Emphysema exacerbator | 71.85 | 18.46 | ||

| E. with chronic bronchitis | 70.25 | 10.86 | ||

| PBD positive | 77.01 | 16.94 | ||

| Height (m) | Non-exacerbator | 1.63 | 0.07 | 0.075 |

| Emphysema exacerbator | 1.61 | 0.08 | ||

| E. with chronic bronchitis | 1.61 | 0.08 | ||

| PBD positive | 1.65 | 0.09 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Non-exacerbator | 28.48 | 5.83 | 0.365 |

| Emphysema exacerbator | 27.47 | 6.19 | ||

| E. with chronic bronchitis | 26.82 | 3.55 | ||

| PBD positive | 28.15 | 5.44 | ||

| FEV1 (mL) | Non-exacerbator | 1197.11 | 385.43 | 0.000 |

| Emphysema exacerbator | 1085.56 | 439.09 | ||

| E. with chronic bronchitis | 988.00 | 309.79 | ||

| PBD positive | 1450.70 | 414.77 | ||

| Charlson | Non-exacerbator | 2.00 | 1.00–4.00 | 0.082 |

| Emphysema exacerbator | 2.00 | 1.00–3.00 | ||

| E. with chronic bronchitis | 3.00 | 1.25–4.00 | ||

| PBD positive | 2.00 | 1.00–3.00 | ||

SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; PBD: bronchodilator test; E: Exacerbator; BMI: body mass index; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in the first second.

Comparison of the general characteristics of the patients based on the phenotypes according to GesEPOC 2021.

| Variable | Phenotype GesEPOC 2021 | N/mean/median | %/SD/IQR | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n) | Non-exacerbator | 171 | 90.0 | 0.725 |

| Non-eosinophilic exacerbator | 60 | 87.0 | ||

| Eosinophilic exacerbator | 12 | 85.7 | ||

| Age (years) | Non-exacerbator | 67.74 | 10.47 | 0.820 |

| Non-eosinophilic exacerbator | 68.68 | 10.92 | ||

| Eosinophilic exacerbator | 68.00 | 11.79 | ||

| Active smoking (n) | Non-exacerbator | 67 | 35.3 | 0.534 |

| Non-eosinophilic exacerbator | 22 | 31.9 | ||

| Eosinophilic exacerbator | 3 | 21.4 | ||

| Weight (kg) | Non-exacerbator | 75.79 | 17.63 | 0.506 |

| Non-eosinophilic exacerbator | 73.58 | 14.97 | ||

| Eosinophilic exacerbator | 71.93 | 15.18 | ||

| Height (m) | Non-exacerbator | 1.64 | 0.08 | 0.547 |

| Non-eosinophilic exacerbator | 1.62 | 0.08 | ||

| Eosinophilic exacerbator | 1.63 | 0.08 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Non-exacerbator | 28.20 | 5.74 | 0.721 |

| Non-eosinophilic exacerbator | 27.82 | 4.92 | ||

| Eosinophilic exacerbator | 27.13 | 4.99 | ||

| FEV1 (mL) | Non-exacerbator | 1269.32 | 402.50 | 0.012 |

| Non-eosinophilic exacerbator | 1096.81 | 396.87 | ||

| Eosinophilic exacerbator | 1185.00 | 577.72 | ||

| Charlson | Non-exacerbator | 2.00 | 1.00–3.00 | 0.156 |

| Non-eosinophilic exacerbator | 2.00 | 1.00–3.50 | ||

| Eosinophilic exacerbator | 3.50 | 1.75–5.00 | ||

SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; BMI: body mass index; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in the first second.

Figs. 1 and 2 illustrate the survival of COPD patients according to the phenotypes defined by GesEPOC 2017 and GesEPOC 2021, respectively. There are some significant differences between the survival curves, and the exacerbator patients with chronic bronchitis and the non-eosinophilic exacerbator patients had lower survival in their respective classifications (p<0.001 and p=0.034, respectively).

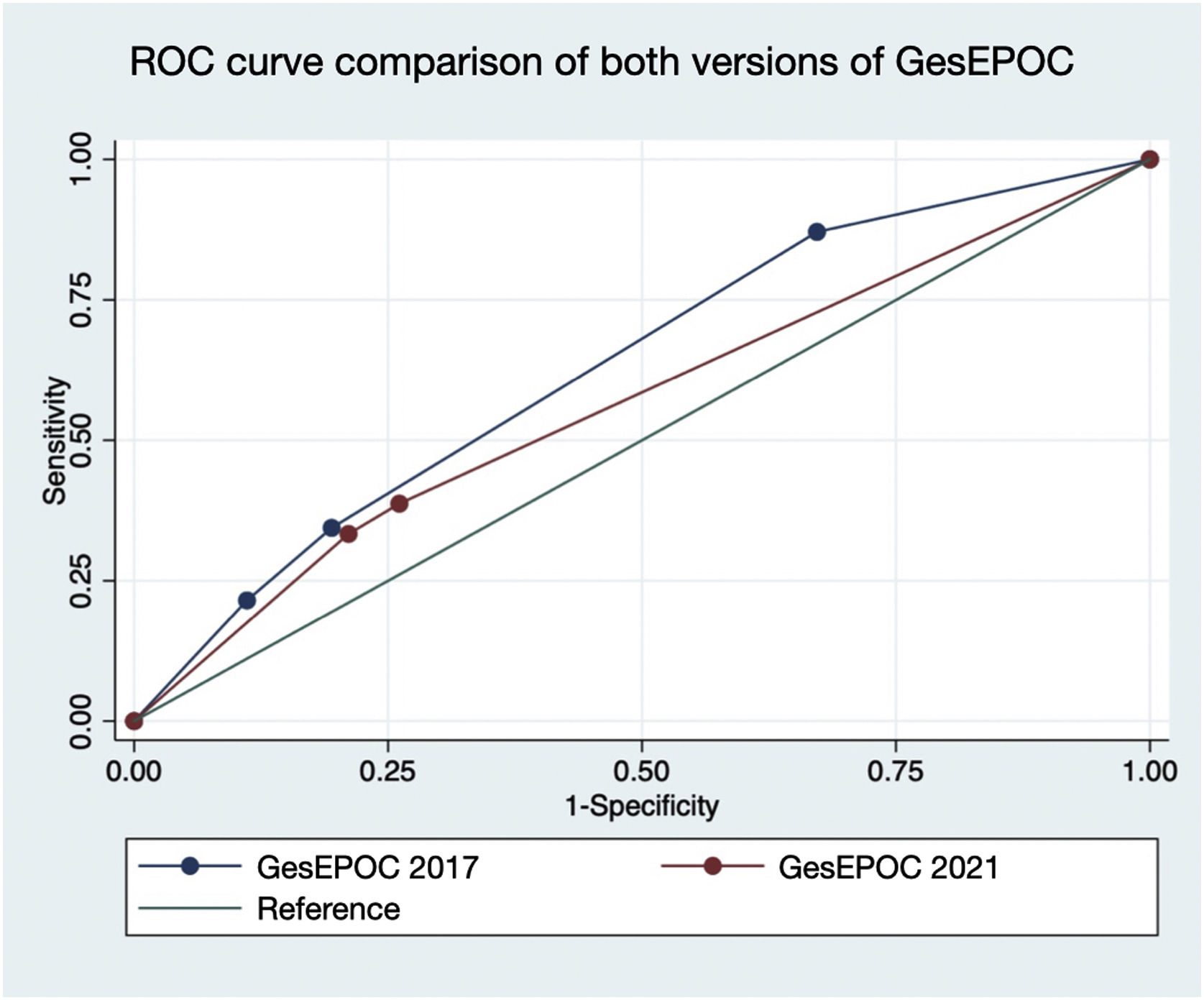

Fig. 3 represents the comparison of the area under the ROC curve of both versions of GesEPOC. A greater area under the curve was observed for GesEPOC 2017 compared to GesEPOC 2021 (0.632 vs 0.566, p=0.018).

Table 3 shows the risk factors independently associated with mortality. These were advanced age (hazard ratio [HR] 1.06; 95% confidence interval [CI] 95% 1.02–1.08; p<0.001), non-eosinophilic exacerbator phenotype (HR 1.74; 95% CI 1.10–2.73; p=0.017) and a high score on the Charlson index (HR 1.33; 95% CI 1.18–1.49; p<0.001). In contrast, elevated FEV1 measured in absolute value was identified as a protective factor (HR 0.89; 95% CI 0.83–0.96; p=0.002).

Risk factors independently associated with mortality.

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.06 | 1.02–1.08 | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.88 | 0.73–4.86 | 0.193 |

| FEV1(in 100mL) | 0.89 | 0.83–0.96 | 0.002 |

| Phenotypes | |||

| Non-exacerbator | ref | ref | ref |

| Non-eosinophilic exacerbator | 1.74 | 1.10–2.73 | 0.017 |

| Eosinophilic exacerbator | 0.85 | 0.33–2.16 | 0.732 |

| Active smoking | 1.30 | 0.81–2.09 | 0.282 |

| Charlson | 1.33 | 1.18–1.49 | <0.001 |

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in the first second; ref: reference; CI: confidence interval.

The main conclusion of this study was the lower survival of non-eosinophilic exacerbator patients compared to non-exacerbator patients. Additionally, the new classification by phenotypes of the 2021 GesEPOC predicts the survival of patients with COPD worse compared to the 2017 GesEPOC.

This difference in survival between non-eosinophilic and non-exacerbator patients could be related to the severity and frequency of exacerbations, whose predictive role in mortality has been described in previous studies.6–8

In our study, the non-eosinophilic exacerbator phenotype was a risk factor independently associated with mortality. The absence of eosinophilia could contribute to the lower survival of non-eosinophilic exacerbator patients. This is because eosinophilia in peripheral blood reflects a Th2-dependent inflammation, characteristic of patients with bronchial asthma and in response to inhaled corticosteroids, which by itself could confer a better prognosis to patients who present it.9–12

Decreased FEV1 has been described on numerous occasions as a poor prognostic factor in COPD since the discoveries of Burrows et al.13 In addition, studies by Cabrera López et al.14 and Golpe et al.15 confirm the prognostic capacity of this lung function parameter and its correct inclusion in the risk stratification of COPD patients according to the classification of GesEPOC. Our finding that a high FEV1 is a protective factor for mortality in COPD patients is consistent with the previously mentioned studies.

In our study, advanced age was a risk factor independently associated with mortality. Advanced age in patients with COPD is a well-known poor prognostic factor since these patients present defective cell repair, as well as a disorder in some of the molecules involved in protection against ageing, so it can develop an additive effect.16–18

On the other hand, our study showed that, as the presence of comorbidities, measured by the Charlson index, increased, the prognosis of these patients worsened. This finding is consistent with those of the GesEPOC Working Group,19 Diaz Moreno et al.20 and Vázquez et al.21 On the other hand, Almagro et al.22 and Aramburu et al.23 reported comorbidity as a risk factor independently associated with mortality. This is because many of the comorbidities present in these patients share the same routes or processes of accelerated ageing, as well as risk factors, such as smoking. However, studies such as SUMMIT24 show that it has not been possible to demonstrate that COPD is a clue in the pathogenesis of different comorbidities.

Active smoking at the time of inclusion in the study could not be demonstrated as an independent risk factor for mortality in our study, which could be explained by the high percentage of patients who had quit smoking. In this sense, the literature shows inconclusive results.25

There are few published data on the mortality of COPD patients according to the GesEPOC 2021 classification. Recently, Golpe et al.26 published a study with a similar methodology, applying this classification to a previously existing cohort of COPD patients, concluding that low-risk patients had less mortality, but without finding significant differences between the 3 phenotypes. This difference with the results of our study could be justified because we have not considered the distinction between low-risk and high-risk patients, understanding that the concept of low-risk patients is to simplify the management of patients with mild COPD in primary care.

Lastly, we found a loss of mortality predictive power of the 2021 GesEPOC classification compared to the 2017 GesEPOC, which could be justified by the mere fact of presenting one fewer category in the phenotype classification. It is true that the objective of the classification into phenotypes is to facilitate the individualized management of patients with COPD and not so much to predict the evolution of the patients, but rather the expected evolution could condition the management of the patients. In this study, only the capacity to predict mortality was analyzed, but it would also be interesting to analyze other aspects of the disease in future studies, such as the probability of having exacerbations.

The present study has some limitations. First, it did not consider patients with mild COPD. This is because differences in mortality are less likely to be found in milder patients regardless of their phenotype. In any case, when extrapolating the results of this study to the general population, it must be considered that this sample is not representative of patients with mild COPD.

Second, we used a modified version of the GesEPOC 2017 to compare with the GesEPOC 2021 clasification, because we consider that the ACO phenotype proposed by this guideline has high specificity but low sensitivity when considering a very positive response in the bronchodilator test. We proposed a different phenotype to improve this sensitivity, with a positive response in the bronchodilator test. In this modified version, we also did not consider eosinophil levels or classification into high-risk and low-risk patients. The results obtained in this study could be different if we consider the original definition of the GesEPOC 2017.

Third, the classification into different phenotypes was based on the initial characteristics of the patients at the time of inclusion in the study. This may be a limitation due to the evolution of the disease, with it being possible for patients to develop characteristics different from those of the initial phenotype in which they were classified. This study intended to classify the patients from the initial moment, and from these data, to predict the evolution of the patient over the subsequent years.

Finally, there are some other minor limitaciones: (1) Our cohort was predominantly male, due to the characteristics of the disease itself. This fact could make this sample not representative of the female population. (2) The sample size is small, and there are few patients in some phenotypes. This could affect the statistical power in certain comparisons. (3) Dyspnea is a variable strongly associated with mortality, but it was not included among the study variables. This fact was due to that the comparison of dyspnea was not an objective of the study. When interpreting the mortality data, it must be taken into account that the severity of dyspnea was not considered.

In conclusion, patients with non-eosinophilic exacerbator COPD had lower survival compared to non-exacerbator patients according to the GesEPOC 2021 classification. Advanced age, non-eosinophilic exacerbator phenotype and greater presence of comorbidities measured by the Charlson index were identified as risk factors independently associated with mortality. The GesEPOC 2021 classification had less ability to predict mortality compared to the previous version from 2017. When applying the new GesEPOC 2021 phenotype definition, it is important to take these data into account to offer more individualized management to COPD patients.

Informed consentThe authors confirm that written consent has been obtained from all patients.

FundingMenarini supported this study with an unconditional scholarship.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest directly or indirectly related to the contents of this manuscript.

Authors' contributionsConceptualization: Zichen Ji, Julio Hernández-Vázquez and Javier de Miguel-Díez

Methodology: Zichen Ji, Julio Hernández-Vázquez and Javier de Miguel-Díez

Software: José María Bellón-Cano

Validation: Irene Milagros Domínguez-Zabaleta, Marta Esteban-Yagüe and Paula García-Valentín

Formal analysis: José María Bellón-Cano

Investigation: Ismael Ali-García, Carmen Matesanz-Ruiz and María Jesús Buendía-García

Resources: Julio Hernández-Vázquez and Javier de Miguel-Díez

Data curation: José María Bellón-Cano and Irene Milagros Domínguez-Zabaleta

Writing – original draft preparation: Marta Esteban-Yagüe and Paula García-Valentín

Writing – review and editing: Julio Hernández-Vázquez and Javier de Miguel-Díez

Visualization: José María Bellón-Cano

Supervision: Julio Hernández-Vázquez and Javier de Miguel-Díez

Project administration: Javier de Miguel-Díez

Funding acquisition: Julio Hernández-Vázquez