This review gives a comprehensive and nuanced appraisal of the current state of Intermediate Respiratory Care Units (IRCUs). It aims to evaluate the distribution of IRCUs in Spain, identify challenges and gaps in the current system and analyze the impact of IRCUs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A review of the evolution and current state of IRCUs was conducted. A search was performed on PubMed. Original articles were selected for analysis. Additionally, recommendation documents on IRCUs from SEPAR and other Scientific Societies were reviewed. The review analyzes the history and evolution of the IRCUs, their role and function, IRCU models, the evolution of admission criteria, and their efficacy and efficiency.

IRCUs offer significant benefits by improving patient outcomes through accurate categorization and specialized treatment of severe pulmonary diseases, ensuring high-quality care. They reduce ICU admission rates, resulting in substantial cost savings for hospitals.

Our analysis indicates that while IRCUs contribute positively to patient outcomes and resource optimization in Spain, there are significant challenges related to heterogeneity in unit structures, staffing, and resource allocation. Standardizing definitions and models may enhance the effectiveness and comparability of IRCUs across the healthcare system.

Esta revisión ofrece una valoración completa y matizada del estado actual de las unidades de cuidados respiratorios intermedios (UCRIs). Pretende evaluar la distribución de las UCRI en España, identificar los desafíos y las brechas en el sistema actual, y analizar el impacto de las UCRIs durante la pandemia de COVID-19.

Se realizó una revisión de la evolución y estado actual de las UCRIs. Se realizó una búsqueda en PubMed. Se seleccionaron artículos originales para su análisis. Además, se revisaron documentos de recomendaciones sobre UCRIs de la SEPAR y otras sociedades científicas. La revisión analiza la historia y la evolución de las UCRIs, su papel y función, los modelos de UCRIs, la evolución de los criterios de ingreso y su eficacia y eficiencia.

Las UCRIs ofrecen beneficios significativos al mejorar los resultados de los pacientes mediante una categorización precisa y un tratamiento especializado de las enfermedades pulmonares graves, garantizando una atención de alta calidad. Reducen las tasas de ingreso en las UCI, lo que supone un ahorro sustancial de costes para los hospitales.

Nuestro análisis indica que, si bien las UCRIs contribuyen positivamente a los resultados de los pacientes y a la optimización de los recursos en España, existen desafíos importantes relacionados con la heterogeneidad en las estructuras de las unidades, la dotación de personal y la asignación de recursos. La estandarización de definiciones y modelos puede mejorar la eficacia y la comparabilidad de las UCRIs en todo el sistema sanitario.

The Intermediate Respiratory Care Units (IRCUs) are defined by the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) as areas for monitoring and supporting patients with acute respiratory failure (ARF) who require non-invasive respiratory support (NIRS). These incorporate non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV), high-flow oxygen treatment (HFOT), and interventional strategies like bronchoscopy, pleural drainage, thoracic ultrasound, and sedation for NIV among others. IRCUs can treat patients who due to their complexity cannot be treated within the conventional hospital ward, but do not require admission to an Intensive Care Unit (ICU).1,2 These units admit patients who do not need or do not benefit from admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), but due to their complexity, could not receive adequate care in a conventional hospital ward.3 IRCUs allow for continuous monitoring and specific treatments, reducing the burden on ICUs, optimizing resources, and improving clinical outcomes by lowering mortality and costs.3–5

Besides the economic factors, there are other advantages which favor the IRCU as a care site for these patients. Unlike the ICU, the IRCU offers greater privacy and easier visitor access for the patients. This may contribute to the “healing” process and may help facilitate the discharge from hospital, especially for those patients who require long-term oxygen therapy and/or home ventilatory support.6

IRCUs can be structured according to three primary models: the Independent Model, which operates autonomously as its own functional group, allowing for significant patient support but limiting staff flexibility and raising costs; the Parallel Model, positioned adjacent to the ICU, enabling resource sharing and staff rotation while risking under-occupancy if the unit is large; and the Integrated Model, located within the pulmonology ward, ensuring seamless patient transitions and continuity of care but requiring ongoing adjustments in medical and nursing staff due to fluctuating occupancy.7,8

Regarding the physical structure and size of IRCUs, it is important to distinguish between closed IRCUs, with partitions between beds for greater privacy, and open IRCUs, without separators and with central nursing control for greater movement flexibility and supervision. There are other collaborative IRCU models, such as high-dependency areas integrated into emergency departments, where NIV is initiated until patient stabilization is achieved. This approach is particularly useful in hospitals without on-site pulmonologists or those lacking optimal infrastructure for IRCU patient care.1,7,8

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the critical role of Intermediate Respiratory Care Units (IRCUs) as a bridge between general wards and Intensive Care Units (ICUs), particularly in providing specialized respiratory support. IRCUs have demonstrated effectiveness in managing patients requiring non-invasive respiratory support, which has significant implications for patient outcomes and resource allocation within hospitals.9 The Spanish healthcare system, while robust in many respects, faces challenges such as human resource shortages and regional disparities in healthcare provision.10

This underscores the importance of evaluating the current state of IRCUs to identify opportunities for improvement and ensure they effectively contribute to the healthcare system.

While the primary focus of this review is on the evolution, current state, and challenges of IRCUs in Spain, we also incorporate relevant international studies. This approach provides a comparative perspective, allowing us to contextualize the developments within Spain against global trends in respiratory care.

This review seeks to assess the distribution of Intermediate Respiratory Care Units (IRCUs) in Spain, evaluating their capacity in terms of bed availability, examining staffing models and resource allocation, evaluating of admission criteria in IRCUs along time, identifying challenges and deficiencies within the current system, analyzing the role and impact of IRCUs during the COVID-19 pandemic, and offering evidence-based recommendations for future development.

Materials and methodsA comprehensive review of the evolution and current state of IRCUs was conducted, focusing predominantly on Spain. A literature search was performed on PubMed using the MeSH terms ‘Intermediate Respiratory Care Unit.’ Both national and international original articles were selected for analysis to provide a broader context. Additionally, recommendation documents on IRCUs from SEPAR and other relevant scientific societies were reviewed.

ResultsOut of 49 articles identified, 22 were selected for full-text review after initial screening. Following detailed evaluation, 7 articles were excluded due to lower relevance to the study objectives, resulting in 12 articles included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

There are 30 Spanish hospitals accredited by the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) (Table 1).11 They are structured into three levels: Basic Unit, Specialized Unit, and Highly Specialized Unit, differentiated by diagnostic and therapeutic complexity. The distribution of accredited IRCUs in Spain is heterogeneous, with a higher concentration in major metropolitan areas such as Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia. These regions are equipped with multiple specialized and highly complex units, indicating a focus on providing advanced respiratory care. Other regions have fewer accredited units, with a mix of basic and specialized care facilities, reflecting regional healthcare disparities and resource allocation asymmetries. Nonetheless, there is a need for a proper registry of existing IRCUs in our country, accredited or not, to provide a more accurate view of the state of IRCUs in Spain.

Intermediate Respiratory Care Units accredited by SEPAR.

| High complexity specialized units | Specialized units | Basic units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria for excellence | • University Hospital of Cáceres. San Pedro de Alcántara Hospital.• Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí. Sabadell (Barcelona)• Clinical University Hospital of Valencia. Valencia.• University Hospital Gregorio Marañón. Madrid• University Hospital 12 de octubre. Madrid• University Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz. Madrid• University Hospital Ramón y Cajal. Madrid• University Hospital La Princesa. Madrid | • Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital. Galdakao (Vizcaya)• Regional University Hospital of Malaga. Málaga.• Infanta Sofía Hospital. San Sebastián de los Reyes (Madrid)• University Hospital La Paz. Madrid• University Hospital Basurto. Bilbao• University Hospital of Guadalajara. Guadalajara. | • University Hospital Puerta de Hierro de Majadahonda. Madrid |

| No criteria for excellence | • University Hospital Virgen de las Nieves. Granada• Clinical University Hospital San Cecilio. Granada• University Hospital of Getafe (Madrid)• Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital. Badalona (Barcelona)• University Hospital Virgen del Rocío. Sevilla | • University Hospital of A Coruña• University Hospital of Navarra. Pamplona• University Hospital Rey Juan Carlos Móstoles (Madrid) | • University Hospital of León• University Hospital of Santiago de Compostela. (La Coruña)• University Hospitall Clínico San Carlos. Madrid• Los Arcos del Mar Menor Hospital. Pozo Aledo (Murcia)• Central University Hospital of Asturias. Oviedo• University Hospital la Ribera. Alzira (Valencia)• University Hospital Royo Villanova. Zaragoza |

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain, a study on IRCUs revealed that, out of 67 hospitals, 28 (42%) already had IRCUs before the crisis, while 11 (16%) created them specifically to handle the emergency. Before the pandemic, these units had an average of 4.07 beds and a nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:5, with 86% of IRCUs having a respiratory specialist (FEA). During the pandemic, 70% of pre-existing IRCUs were expanded, reaching an average of 14.82 beds, compared to 7.91 beds in newly created IRCUs, with the nurse-to-patient ratio improving to 1:4. Although there was a 74% increase in physicians covering shifts of 12h or more, the number of respiratory specialists present remained stable, and the equipment, such as capnographs and flexible bronchoscopes, did not significantly change.12 Currently, there are no studies comparing IRCU models in terms of efficacy and efficiency, but the integrated model within the pulmonology ward is the most common in Spain.

Evolution of admission criteria in IRCUsThe most commonly used indicators in IRCUs are the WOB score, the SOFA score, the ROX Index, and the HACOR score for NIV. However, regarding clinical practice guidelines or international consensuses that standardize admission criteria for an IRCU, no such standard exists. Table 2 shows the evolution of admission criteria in IRCUs over the past two decades. These criteria are expected to change as IRCUs evolve and adapt to the specific characteristics of each center.

Criteria for admission to IRCU.

| Italian Group – 1998 (30) |

| 1. Patients with a life-threatening respiratory disease, but who do not require short-term endotracheal intubation.2. Patients requiring acute NIV.3. Patients requiring a CPAP mask for respiratory failure.4. Patients with tracheostomy (except if it is of long duration).5. Patients coming from the ICU as an intermediate care de-escalation unit. |

| Working Group on Intermediate Respiratory Care of the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) – 2005 (1) |

| 1. Transfer of stable patients from an ICU with prolonged withdrawal of IMV, to replace it with home care, for example.2. Transfer of patients from an ICU who, once stabilized, still require nursing or physiotherapy care as an intermediate step to conventional hospitalization.3. Need for NIV for the treatment of acute or acute chronic respiratory failure.4. Severe respiratory failure that, although not requiring ventilatory support, is a candidate for noninvasive monitoring.5. Patients following major thoracic surgery or with a significant decrease in expected postoperative pulmonary function, with relevant comorbidity or age over 70 years, as well as when relevant respiratory medical complications appear that arose after the operation.6. Life-threatening hemoptysis. |

| British Thoracic Society Group and the UK Intensive Care Society – 2021 (31) |

| 1. Patients in need of NIV for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure.2. Patients in need of noninvasive CPAP for hypoxemia of respiratory etiology.3. Patients with need for high-flow oxygen therapy for hypoxemia.4. Chronic NIV patient with chronic-acute respiratory failure.5. ICU transfer (step-down, de-escalated) of patients with single-organ respiratory failure, including continued management of tracheostomized/laryngectomized patients and patients in need of mechanical cough support.6. Patients with acute severe asthma crisis.7. Patients with massive pulmonary thromboembolism.8. Other respiratory conditions characterized by an acute need for continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation. |

One of the problems in analyzing the various published studies on IRCUs is the different terminologies previously used, the heterogeneity of definitions, admission criteria, types of underlying respiratory pathology, structure, and human resources. Nevertheless, the results of IRCUs throughout their evolution have been favorable.

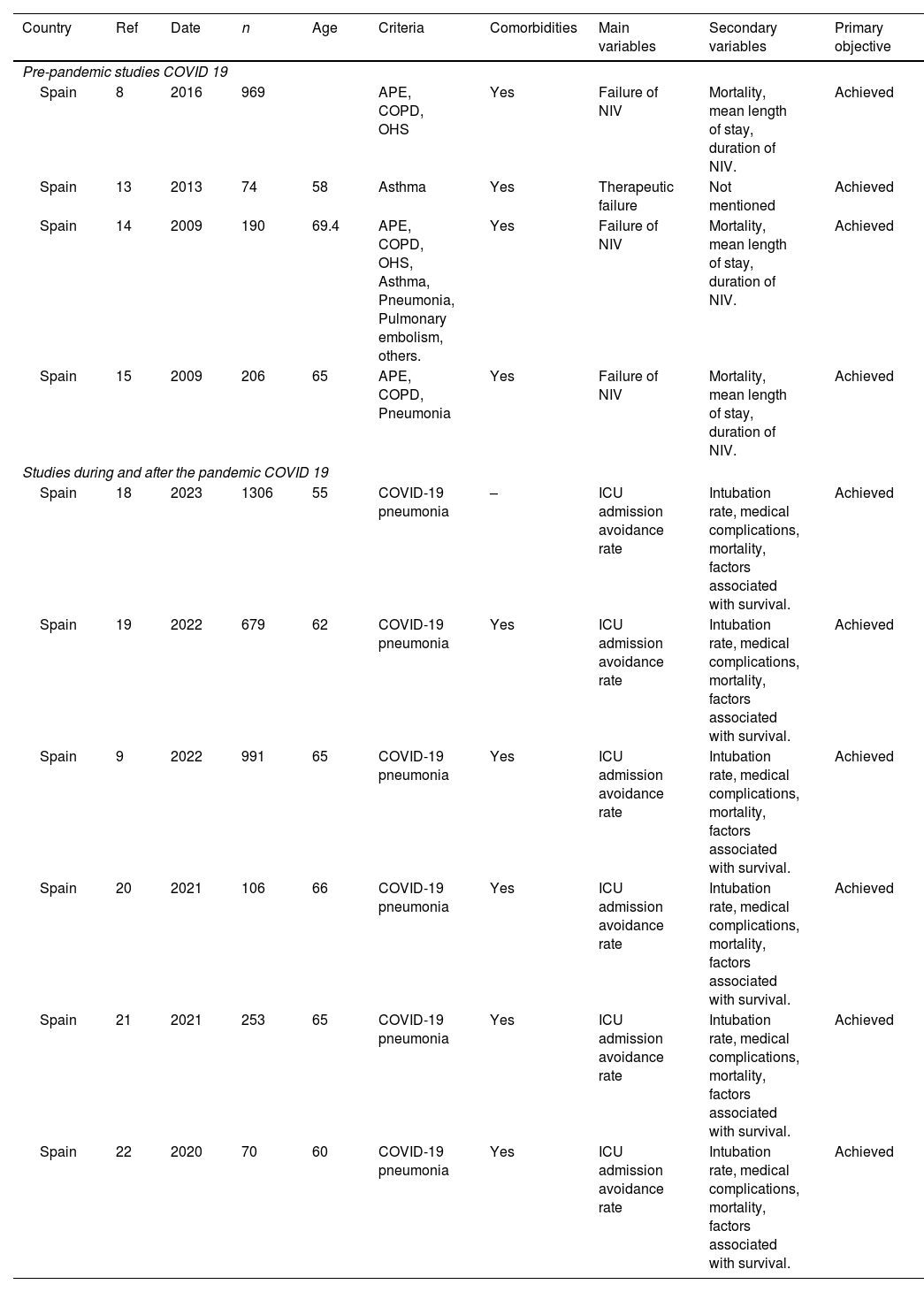

When analyzing the results, we preferred to separate studies conducted before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this analysis are summarized in Table 3.

Summary of the most relevant publications related to IRCUs.

| Country | Ref | Date | n | Age | Criteria | Comorbidities | Main variables | Secondary variables | Primary objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pandemic studies COVID 19 | |||||||||

| Spain | 8 | 2016 | 969 | APE, COPD, OHS | Yes | Failure of NIV | Mortality, mean length of stay, duration of NIV. | Achieved | |

| Spain | 13 | 2013 | 74 | 58 | Asthma | Yes | Therapeutic failure | Not mentioned | Achieved |

| Spain | 14 | 2009 | 190 | 69.4 | APE, COPD, OHS, Asthma, Pneumonia, Pulmonary embolism, others. | Yes | Failure of NIV | Mortality, mean length of stay, duration of NIV. | Achieved |

| Spain | 15 | 2009 | 206 | 65 | APE, COPD, Pneumonia | Yes | Failure of NIV | Mortality, mean length of stay, duration of NIV. | Achieved |

| Studies during and after the pandemic COVID 19 | |||||||||

| Spain | 18 | 2023 | 1306 | 55 | COVID-19 pneumonia | – | ICU admission avoidance rate | Intubation rate, medical complications, mortality, factors associated with survival. | Achieved |

| Spain | 19 | 2022 | 679 | 62 | COVID-19 pneumonia | Yes | ICU admission avoidance rate | Intubation rate, medical complications, mortality, factors associated with survival. | Achieved |

| Spain | 9 | 2022 | 991 | 65 | COVID-19 pneumonia | Yes | ICU admission avoidance rate | Intubation rate, medical complications, mortality, factors associated with survival. | Achieved |

| Spain | 20 | 2021 | 106 | 66 | COVID-19 pneumonia | Yes | ICU admission avoidance rate | Intubation rate, medical complications, mortality, factors associated with survival. | Achieved |

| Spain | 21 | 2021 | 253 | 65 | COVID-19 pneumonia | Yes | ICU admission avoidance rate | Intubation rate, medical complications, mortality, factors associated with survival. | Achieved |

| Spain | 22 | 2020 | 70 | 60 | COVID-19 pneumonia | Yes | ICU admission avoidance rate | Intubation rate, medical complications, mortality, factors associated with survival. | Achieved |

Ref: reference. N: number of participants. APE: acute pulmonary edema. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. OHS: obesity and hypoventilation syndrome. NIV: noninvasive ventilation. –: not mentioned in the article.

Studies reviewed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, conducted mainly in England and Spain, systematically demonstrated positive outcomes concerning primary variables (NIV failure or therapeutic failure) and secondary variables (mortality, average length of stay, duration of NIV) for patients treated in IRCUs. These units effectively treated patients with various severe respiratory conditions, such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Acute Respiratory Failure (ARF), Severe Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure (SHRF), asthma, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolism.1,8,13–17

The body of studies analyzed during the pandemic highlights the efficacy of IRCUs in treating COVID-19 pneumonia. These units significantly contributed to preventing ICU admissions and reducing the need for intubation. Additionally, they effectively managed associated medical complications. The positive results from various studies underscore the fundamental role of IRCUs in optimizing patient care and resource utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic.9,18–22

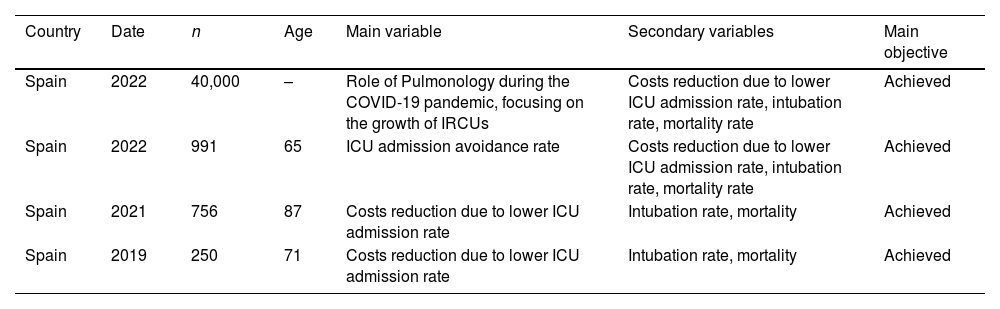

The studies analyzing the efficiency of these units are summarized in Table 4.5,9,12,23 They demonstrate that reducing ICU admission rates leads to a significant reduction in costs. Additionally, they show a positive impact on secondary outcomes, such as reducing intubation rates and decreasing mortality.

Studies analyzing the cost and mortality analyses of patients attended in the IRCUs.

| Country | Date | n | Age | Main variable | Secondary variables | Main objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 2022 | 40,000 | – | Role of Pulmonology during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the growth of IRCUs | Costs reduction due to lower ICU admission rate, intubation rate, mortality rate | Achieved |

| Spain | 2022 | 991 | 65 | ICU admission avoidance rate | Costs reduction due to lower ICU admission rate, intubation rate, mortality rate | Achieved |

| Spain | 2021 | 756 | 87 | Costs reduction due to lower ICU admission rate | Intubation rate, mortality | Achieved |

| Spain | 2019 | 250 | 71 | Costs reduction due to lower ICU admission rate | Intubation rate, mortality | Achieved |

N: number of participants. ICU: intensive care unit. Bibliographic references in order of appearance.17,6,32,33

To better understand the disease burden of patients treated in this type of intermediate unit, compare performance among IRCUs in different healthcare settings, allocate financial resources effectively, and identify potential areas for improvement, one possibility is to study them from the perspective of Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs). Only one observational study has been conducted in 26 Italian IRCUs.24 It compared the ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision) and ICD-9-CM (Clinical Modification) classification systems and found that ICD-9-CM provided a more accurate categorization of patients and higher DRG scores, resulting in better recognition of respiratory failures and significant economic advantages. Both systems are rooted in the same diagnostic framework, the ICD-9-CM is a more detailed, clinically focused adaptation designed for practical application in healthcare settings in the U.S. The average patient weight was 2.05 using ICD-9, compared to 2.53 when applying ICD-9-CM. Additionally, significant discrepancies arose regarding DRG scores, leading to an economic underestimation of IRCU activities. This emphasizes the importance of reviewing DRG compensation to ensure a high degree of alignment with the clinical complexity of these units. In this regard, it would be prudent to update the group assignments to the new ICD-10 version and verify its adequacy, as well as review the application of APR-DRGs as a more common patient classification in Spain.

DiscussionIRCUs offer significant benefits by improving patient outcomes through accurate categorization and specialized treatment of severe pulmonary diseases, ensuring high-quality care. They reduce ICU admission rates, resulting in substantial cost savings and improved financial reimbursements for hospitals. IRCUs optimize healthcare resources by minimizing length of stay and efficiently utilizing medical procedures. Additionally, these units provide better management of respiratory failure, reducing complications and improving recovery rates, leading to more efficient and effective healthcare delivery.

A major issue encountered during this review is the heterogeneity in the definitions of IRCUs. The pathologies admitted, operational models, and available resources vary greatly. This inconsistency complicates the comparative evaluation of IRCUs. Furthermore, there is a clear gap in management studies aiming to calculate the care burden of patients in these units. Why? Because there is a lack of studies supporting a solid methodology for such evaluations. Therefore, we advocate for further research in this area. It is crucial to standardize definitions, models, and methodologies. This will enhance the accuracy and comparability of future studies on IRCUs, paving the way for more effective and cohesive healthcare management strategies.

We propose, therefore, to study the feasibility of considering the IRCU as its own Homogeneous Functional Group (HFG), described as the “minimum hospital management unit,” characterized by homogeneous activity, defined objectives, a specific physical location, and usually a single responsible party.

In our initial literature review, we focused on studies describing the structural and staffing characteristics of IRCUs, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the changes these units underwent. However, we did not identify published data that systematically report IRCU bed availability per population unit (e.g., per 100,000 inhabitants), nor did we find centralized databases providing a clear geographic distribution (urban vs. rural) of these units. Given the evolving nature of IRCUs and their relatively recent expansion during the pandemic, standardized national or regional databases on their exact number, distribution, and bed availability are not readily available in the scientific literature or in official public health reports.12

There are different patient flows into this unit, as they may come from the ICU, emergency department, or hospitalization and be transferred back to the ICU, to a ward, or discharged, either due to death or for home follow-up. Comparing the complexity of all these processes, i.e., the various “clinical or hospital pathways” of the patient, would allow for reliable management and efficiency indicators. Concurrently, it would provide additional motivation to evaluate how the passage of patients through IRCUs is reflected in official information sources such as the Minimum Basic Data Set and what admission or exclusion criteria should be established for this specific IRCU model, given its casuistry and structure.

We conclude that IRCUs offer a significant number of benefits, transforming the landscape of respiratory care. ICRUs have been essential in managing patients with COVID-19 and severe respiratory failure, preventing ICU admission for nearly 50% of severe patients, and underscores the need to consolidate these units at a national level.12 These units excel in improving patient outcomes through meticulous categorization and specialized treatment of severe pulmonary conditions, ensuring personalized, high-quality care. IRCUs optimize healthcare resources by making efficient use of medical procedures. However, the path forward is fraught with challenges. One major challenge is the notable heterogeneity in the pathologies admitted, operational models, and available resources, which complicates comparisons and evaluations between different units. Compounding this problem is the significant gap in management studies aimed at calculating the care burden of IRCU patients, largely due to the absence of robust methodologies. Addressing these challenges requires a concerted effort to understand the casuistry managed in IRCUs and thus standardize definitions, models, and methodologies. Such standardization will enhance the accuracy and comparability of future studies, paving the way for more cohesive and effective healthcare management strategies.

By providing a comprehensive analysis of IRCUs, this review aims to inform health policy decisions, healthcare management strategies, and future development plans to enhance the capacity, quality, and sustainability of IRCUs in Spain.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors were involved in the conception and design of the work; acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content.

FundingThis review has not received any funding.

Conflicts of interestCAS has received fees in the last 3 years for giving lectures, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies, or writing publications for (in alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, and Gebro. CAS declares not receiving ever, directly or indirectly, funding from the tobacco industry or its affiliates.

All authors have no conflict of interest related to this topic.