The prevalence of COPD phenotypes that are referred for assessment for lung transplantation is unknown, as well as whether specific phenotype influences post-transplant evolution in those patients who receive it.

Material and methodsAmbispective observational study without intervention. The main objective was to know the prevalence of the different COPD phenotypes of the patients referred for the evaluation of a lung transplant. Secondary objective were to compare their clinical characteristics, to perform an analysis of post-transplant survival or complications according to their phenotype.

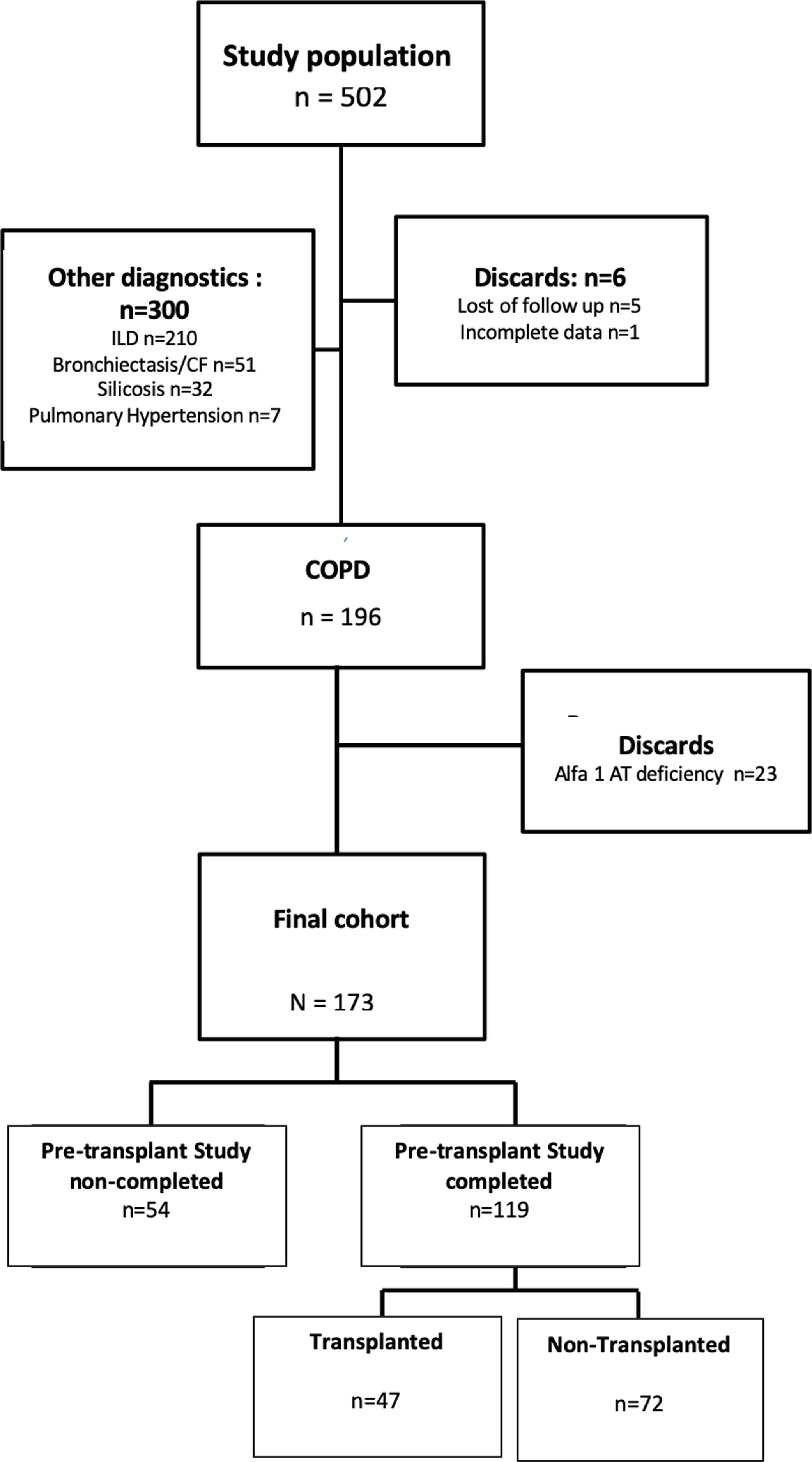

Results502 patients were evaluated for lung transplantation, of which 173 met the study criteria. 31.21% of the patients were discarded for transplantation on a first visit. The final cohort of potential transplant candidates who completed the pre-transplant study was 119 (69%) and 47 finally received a lung transplant (39.5%). The most frequent COPD phenotype evaluated for lung transplantation was the exacerbator (59%), followed by the non-exacerbator (38%) and the Asthma COPD Overlap [ACO] (3%). 59.8% of the exacerbator-phenotype patients assessed did not complete the pre-transplant study. Exacerbator-phenotype patients have a lower post-transplant survival (1115.1 days [standard deviation-DE-587]) vs. ACO: 1432 days [DE 507.5] and Non-exacerbators: 1317.8 days [DE 544.7] p=0.16), although this difference has not been statistically significant.

ConclusionsThe most frequent COPD phenotype assessed for lung transplantation is the exacerbator, although more than half of these patients fail to complete the pre-transplant study.

Se desconoce la prevalencia de los fenotipos de EPOC que son remitidos para valorar el trasplante pulmonar, así como si un fenotipo específico tiene influencia en la evolución postrasplante en aquellos pacientes que lo reciben.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional ambispectivo, sin intervención. El objetivo principal fue conocer la prevalencia de los diferentes fenotipos de EPOC de los pacientes que fueron remitidos para valorar un trasplante de pulmón. Los objetivos secundarios fueron comparar sus características clínicas para realizar un análisis de la supervivencia postrasplante o de las complicaciones de acuerdo con el fenotipo.

ResultadosSe valoró a 502 pacientes para la realización de un trasplante de pulmón, de los cuales 173 cumplían los criterios del estudio. El 31,21% de los pacientes fue descartado para el trasplante en la primera visita. La cohorte final de candidatos potenciales a trasplante que completaron el estudio pretrasplante fue de 119 pacientes (69%) y, finalmente, 47 recibieron el trasplante de pulmón (39,5%). El fenotipo de EPOC que se evaluó con mayor frecuencia para el trasplante de pulmón fue el agudizador (59%), seguido del no agudizador (38%) y el mixto EPOC-asma (3%). El 59,8% de los pacientes con fenotipo agudizador valorados no completó el estudio pretrasplante. Los pacientes con fenotipo agudizador presentan una supervivencia postrasplante más baja (1.115,1 días; desviación estándar [DE]: 587) frente a los mixto EPOC-asma (1.432 días; DE: 507,5) y los no agudizadores (1.317,8 días; DE: 544,7; p=0,16), aunque esta diferencia no fue estadísticamente significativa.

ConclusionesEl fenotipo más frecuentemente estudiado para el trasplante de pulmón es el agudizador, aunque más de la mitad de estos pacientes no completa el estudio pretrasplante.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a very prevalent pathology, and it is associated with high morbidity, mortality and a great burden for health systems.1,2 Approximately 400 million people around the world are affected by COPD,3 constituting the fourth cause of death.

Lung transplantation is the only therapeutic alternative in very severe patients who have progressive deterioration despite receiving a correct treatment. According to the international pulmonary transplant registry data, COPD is the most frequent indication of lung transplantation in the world with a median survival of 6 years after transplantation.4 There is some controversy over whether the transplant provides a significant increase in survival5–7 in COPD, although it has been demonstrated a marked improvement in lung function, gas exchange, stress tolerance and quality of life of patients with this pathology.8 Much of the success of the transplant will reside in an adequate selection of the donor and recipient.9

Since it has been recognized that COPD is a heterogeneous disease characterized by chronic airflow obstruction in which exacerbations and comorbidities can contribute to its severity, an attempt to group patients with similar characteristics that could be associated to a differential clinical outcome has been done by using the term clinical phenotype.10 The approach to the patient based on clinical phenotypes allows them to be classified into subgroups with prognostic value and to determine the most convenient therapy, potentially obtaining better results.11,12 In this way, we have moved from an approach based on the severity of the obstruction to a more personalized approach. After a review of the literature we have not found any scientific work that describes the prevalence of the different COPD phenotypes in patients who are referred for transplantation, nor their potential impact on future evolution if they become transplanted.

Based on the above we have developed this work, where we hypothesize that the distribution of the phenotypes of the patients evaluated for transplantation is not homogeneous and that these clinical phenotypes can influence post-transplant evolution in terms of complications and survival.

Material and methodsStudy design and patientsAmbispective, observational and non-intervention cohort study conducted at the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña (CHUAC), a tertiary hospital which covers a health area of more than 550,000 inhabitants and one of the seven centers in Spain where lung transplantation is performed. The study was conducted between 1/1/2011 and 12/31/2016 and follow-up was carried out until May 1, 2017.

Patients referred to the pulmonary pre-transplant assessment clinic and who had a previous diagnosis of COPD confirmed by spirometry according to GOLD guidelines (Smoking/ex-smoker, FEV1/FVC postbronchodilation<70) were included.13 Those patients who had no prior smoking history, had and alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency or any other major diagnosis of lung disease other than COPD such as bronchiectasis, pneumonia, pulmonary fibrosis or interstitial disease were excluded.

The study meets the ethical standards set out in the Helsinki declaration and was approved by the corresponding Ethics and Clinical Research Committee (# 2012/235).

ObjectivesThe main objective was to know the prevalence of the different COPD phenotypes evaluated for transplantation. To do this, we defined 3 phenotypes: (1) Non-exacerbator: those patients who had less than two moderate exacerbations (the one that required the administration of antibiotics and/or systemic corticosteroids) and none serious (the one that required hospitalization); (2) Exacerbator: defined as those patients who had at least one severe exacerbation or at least two moderate ones separated by four weeks and (3) Asthma-COPD Overlap (ACO): defined by those patients older than 35 years, with cumulative tobacco consumption of more than 10 pack-years and the criteria defined by Gesepoc guidelines.14

As secondary objectives we propose to know the post-transplant survival according to the phenotype and complications defined by the developing of acute and chronic rejection episodes.

Methodology of collection of cases and variables studiedThe patients were attended by the usual care team and the care they received was based on the usual clinical practice and the protocols of the center. Sociodemographic, analytical, functional and clinical data were collected from the lung transplant clinic database and the severity of COPD was determined based on BODE. Patients were included in the transplant waiting list in accordance with the recommendations of the International Society of Heart Lung Transplantation criteria (ISHLT)9 and after a multidisciplinary evaluation by members of the CHUAC Pulmonary Transplant Unit, mainly composed of by pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons and anesthetists.

According to the center protocol, the immunosuppressive treatment consisted of triple therapy, including basiliximab for induction, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and steroids in all cases. For the diagnosis of acute rejection, the findings of transbronchial biopsy and the exclusion of infection or alterations in bronchial sutures were employed. Chronic graft dysfunction (DCI) was defined as a fall in expiratory volume forced in the first second of at least 20% compared to the two best postoperative values in the absence of other causes. Survival was determined based on the last date of contact with the health system and those in which there was any doubt it was confirmed by telephone call.

Statistic analysisCategorical variables are described as frequencies (percentages) with the confidence interval and continuous variables such as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range depending on their distribution. For the comparison of proportions and univariate associations between categorical variables, Chi2 or Pearson's test will be used when appropriate and ANOVA for the comparison of continuous variables between the different phenotypes. Kaplan-Meier curves are described and survival based on the COPD phenotype in transplant patients is compared using a log Rank test. All statistical analyzes were performed with a computerized statistical program (Stata for Mac O.S, version 13.0; Statacorp Inc.; USA). Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

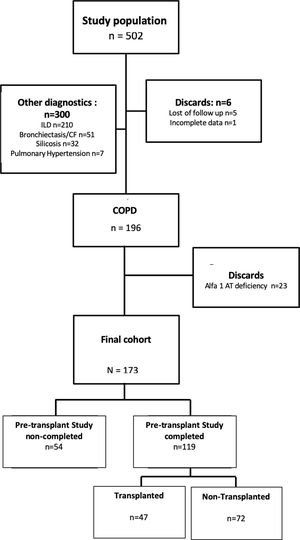

ResultsOf the 502 patients analyzed, 196 (39%) had a diagnosis of COPD. After excluding 23 patients diagnosed with emphysema due to alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, we defined a final cohort of 173 patients. The flow chart of these patients can be seen in Fig. 1.

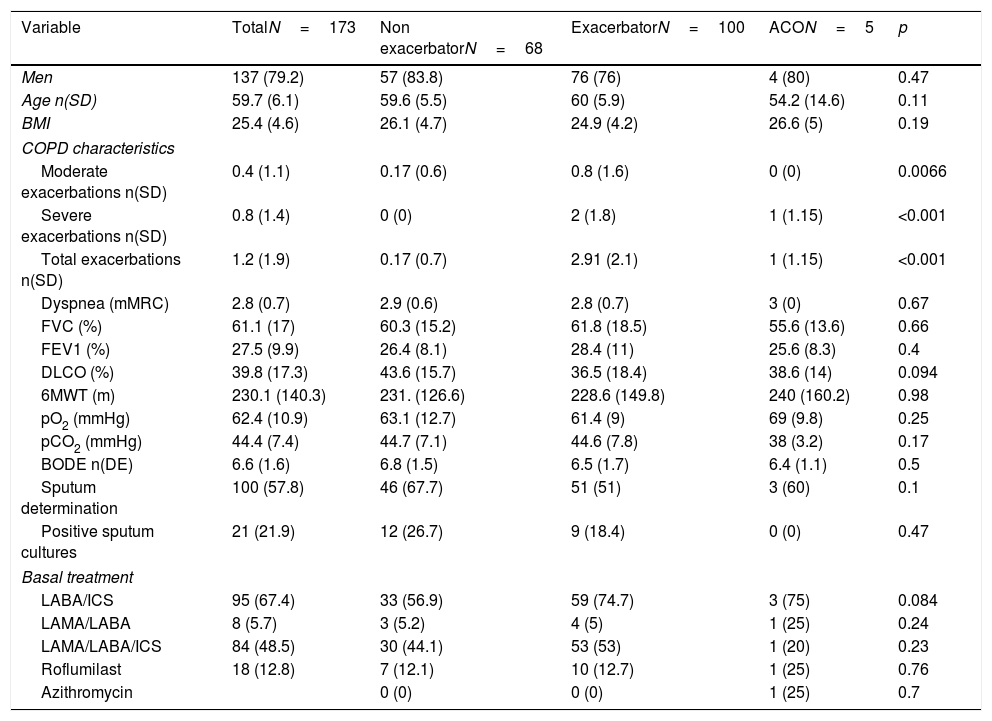

The main characteristics of the patients evaluated for transplantation are shown in Table 1. The patients studied were mainly men (79.2%), with a mean age of 59.7 years (Standard deviation [SD] 6.1), and a very severe obstruction (forced expiratory volume in the first second [FEV1] average of 27.5% [SD 9.9]), patients have 1.2 (SD 1.9) exacerbations on average in the previous year, a BODE of 6.6 (SD 1.6) and around half of the patients were treated with triple therapy.

Classification of patients assessed for transplantation and distribution by phenotypes. Comparative clinical characteristics.

| Variable | TotalN=173 | Non exacerbatorN=68 | ExacerbatorN=100 | ACON=5 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 137 (79.2) | 57 (83.8) | 76 (76) | 4 (80) | 0.47 |

| Age n(SD) | 59.7 (6.1) | 59.6 (5.5) | 60 (5.9) | 54.2 (14.6) | 0.11 |

| BMI | 25.4 (4.6) | 26.1 (4.7) | 24.9 (4.2) | 26.6 (5) | 0.19 |

| COPD characteristics | |||||

| Moderate exacerbations n(SD) | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.17 (0.6) | 0.8 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 0.0066 |

| Severe exacerbations n(SD) | 0.8 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.15) | <0.001 |

| Total exacerbations n(SD) | 1.2 (1.9) | 0.17 (0.7) | 2.91 (2.1) | 1 (1.15) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea (mMRC) | 2.8 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.6) | 2.8 (0.7) | 3 (0) | 0.67 |

| FVC (%) | 61.1 (17) | 60.3 (15.2) | 61.8 (18.5) | 55.6 (13.6) | 0.66 |

| FEV1 (%) | 27.5 (9.9) | 26.4 (8.1) | 28.4 (11) | 25.6 (8.3) | 0.4 |

| DLCO (%) | 39.8 (17.3) | 43.6 (15.7) | 36.5 (18.4) | 38.6 (14) | 0.094 |

| 6MWT (m) | 230.1 (140.3) | 231. (126.6) | 228.6 (149.8) | 240 (160.2) | 0.98 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 62.4 (10.9) | 63.1 (12.7) | 61.4 (9) | 69 (9.8) | 0.25 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 44.4 (7.4) | 44.7 (7.1) | 44.6 (7.8) | 38 (3.2) | 0.17 |

| BODE n(DE) | 6.6 (1.6) | 6.8 (1.5) | 6.5 (1.7) | 6.4 (1.1) | 0.5 |

| Sputum determination | 100 (57.8) | 46 (67.7) | 51 (51) | 3 (60) | 0.1 |

| Positive sputum cultures | 21 (21.9) | 12 (26.7) | 9 (18.4) | 0 (0) | 0.47 |

| Basal treatment | |||||

| LABA/ICS | 95 (67.4) | 33 (56.9) | 59 (74.7) | 3 (75) | 0.084 |

| LAMA/LABA | 8 (5.7) | 3 (5.2) | 4 (5) | 1 (25) | 0.24 |

| LAMA/LABA/ICS | 84 (48.5) | 30 (44.1) | 53 (53) | 1 (20) | 0.23 |

| Roflumilast | 18 (12.8) | 7 (12.1) | 10 (12.7) | 1 (25) | 0.76 |

| Azithromycin | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 0.7 | |

SD: standard deviation; ACO: asthma COPD overlap; BMI: body mass index; CVF: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced espiratory volume in the first second; DLCO: carbon monoxide diffusion; 6MWT: six minute walking test; BODE: Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea and Excercise capacity index; LAMA: Long Acting Muscarinic Antagonist; LABA: Long Acting Beta Agonist; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids.

The most COPD phenotype evaluated for transplantation was the exacerbator (59%), followed by the non-exacerbator (38%) and the ACO (3%). From all of the patients assessed for transplantation, 54 (31.21%) were discarded for lung transplantation in a first consultation. The final cohort of patients who completed the pre-transplant study and potential transplant candidates was 119. Among the most frequent causes of exclusion were the presence of significant comorbidities (29.5%), patient's refusal (7.5%), history of neoplastic process (6%), active smoking (3.5%) or lack of indication at that time (3%).

Characteristics of patients assessed according to the phenotypeNo differences were found regarding the demographic, clinical or therapeutic characteristics between the different phenotypes, except those related to the number and type of exacerbations, a defining characteristic of one of the phenotypes (Table 1).

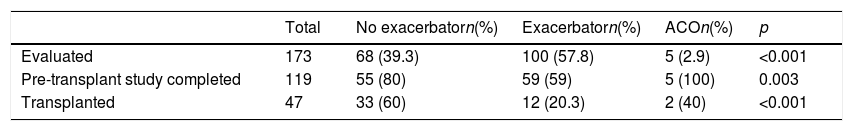

However, we observe that there are significant differences when completing the pre-transplant study and being a potential transplant candidate, being more frequent that this happens in COPD patients with ACO phenotype (100%), compared to the non-exacerbator (80%) or the exacerbators (59%) (p=0.003) (Table 2).

Distribution of the COPD phenotypes of the patients according to whether they were evaluated for transplantation, the pre-transplant study was completed or if they were finally transplanted.

| Total | No exacerbatorn(%) | Exacerbatorn(%) | ACOn(%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluated | 173 | 68 (39.3) | 100 (57.8) | 5 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Pre-transplant study completed | 119 | 55 (80) | 59 (59) | 5 (100) | 0.003 |

| Transplanted | 47 | 33 (60) | 12 (20.3) | 2 (40) | <0.001 |

Of the patients who completed the study, 47 (39.5%) were finally transplanted. The causes that justified the non-transplantation of the 72 remaining patients were the presence of significant comorbidities (32%), previous unknown neoplasia (11.1%), patient refusal (11.1%), clinical stability (6.7%) and age (5.5%). When comparing patients who finally were transplanted with those who did not (Table 3), it was observed that those who were transplanted had less exacerbations in the previous year (0.87 [SD 1.5] vs. 1.8 [SD 2.5]; p=0.035), had more dyspnea (3.15 [SD 0.5] vs. 2.81 [SD 0.6]; p=0.0021) and a higher BODE (7.4 [SD 1.4] vs. 6.4 [SD 1.7]; p=0.0026).

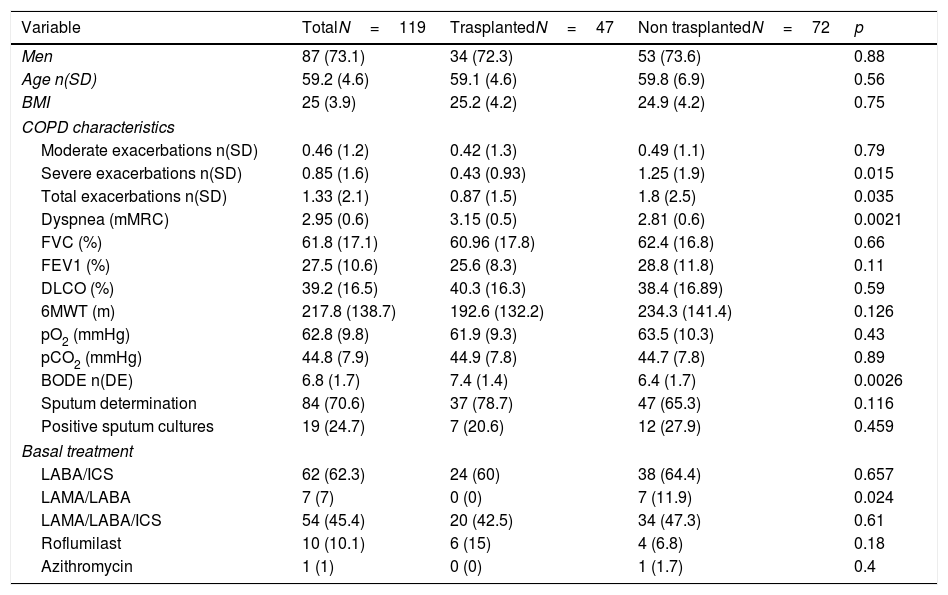

Classification of patients assessed with a complete pre-transplant study according to whether they were finally transplanted.

| Variable | TotalN=119 | TrasplantedN=47 | Non trasplantedN=72 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 87 (73.1) | 34 (72.3) | 53 (73.6) | 0.88 |

| Age n(SD) | 59.2 (4.6) | 59.1 (4.6) | 59.8 (6.9) | 0.56 |

| BMI | 25 (3.9) | 25.2 (4.2) | 24.9 (4.2) | 0.75 |

| COPD characteristics | ||||

| Moderate exacerbations n(SD) | 0.46 (1.2) | 0.42 (1.3) | 0.49 (1.1) | 0.79 |

| Severe exacerbations n(SD) | 0.85 (1.6) | 0.43 (0.93) | 1.25 (1.9) | 0.015 |

| Total exacerbations n(SD) | 1.33 (2.1) | 0.87 (1.5) | 1.8 (2.5) | 0.035 |

| Dyspnea (mMRC) | 2.95 (0.6) | 3.15 (0.5) | 2.81 (0.6) | 0.0021 |

| FVC (%) | 61.8 (17.1) | 60.96 (17.8) | 62.4 (16.8) | 0.66 |

| FEV1 (%) | 27.5 (10.6) | 25.6 (8.3) | 28.8 (11.8) | 0.11 |

| DLCO (%) | 39.2 (16.5) | 40.3 (16.3) | 38.4 (16.89) | 0.59 |

| 6MWT (m) | 217.8 (138.7) | 192.6 (132.2) | 234.3 (141.4) | 0.126 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 62.8 (9.8) | 61.9 (9.3) | 63.5 (10.3) | 0.43 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 44.8 (7.9) | 44.9 (7.8) | 44.7 (7.8) | 0.89 |

| BODE n(DE) | 6.8 (1.7) | 7.4 (1.4) | 6.4 (1.7) | 0.0026 |

| Sputum determination | 84 (70.6) | 37 (78.7) | 47 (65.3) | 0.116 |

| Positive sputum cultures | 19 (24.7) | 7 (20.6) | 12 (27.9) | 0.459 |

| Basal treatment | ||||

| LABA/ICS | 62 (62.3) | 24 (60) | 38 (64.4) | 0.657 |

| LAMA/LABA | 7 (7) | 0 (0) | 7 (11.9) | 0.024 |

| LAMA/LABA/ICS | 54 (45.4) | 20 (42.5) | 34 (47.3) | 0.61 |

| Roflumilast | 10 (10.1) | 6 (15) | 4 (6.8) | 0.18 |

| Azithromycin | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 0.4 |

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; CVF: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced exhaled volume in the first second; DLCO: carbon monoxide diffusion; 6MWT: six minute walking test; BODE: Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea and Excercise capacity index; LAMA: Long Acting Muscarinic Antagonist; LABA: Long Acting Beta Agonist; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids.

We found that there are differences in the probability of being transplanted depending on the clinical phenotype of the patient, being more likely to receive a lung transplant in non-exacerbating phenotypes (60%) compared to ACO (40%) or exacerbators (20.3%); p<0.001 (Table 2). Regarding the distribution of the type of transplant, 19 (40.4%) patients received right unipulmonary transplant, 14 (29.8%) left unipulmonary transplant and 14 (29.8%) received bipulmonary transplant. There was a non-significant greater indication of bipulmonary transplantation in the exacerbator phenotype (36.4%), compared to the non-exacerbator (16.6%) or ACO (0%); p=0.119.

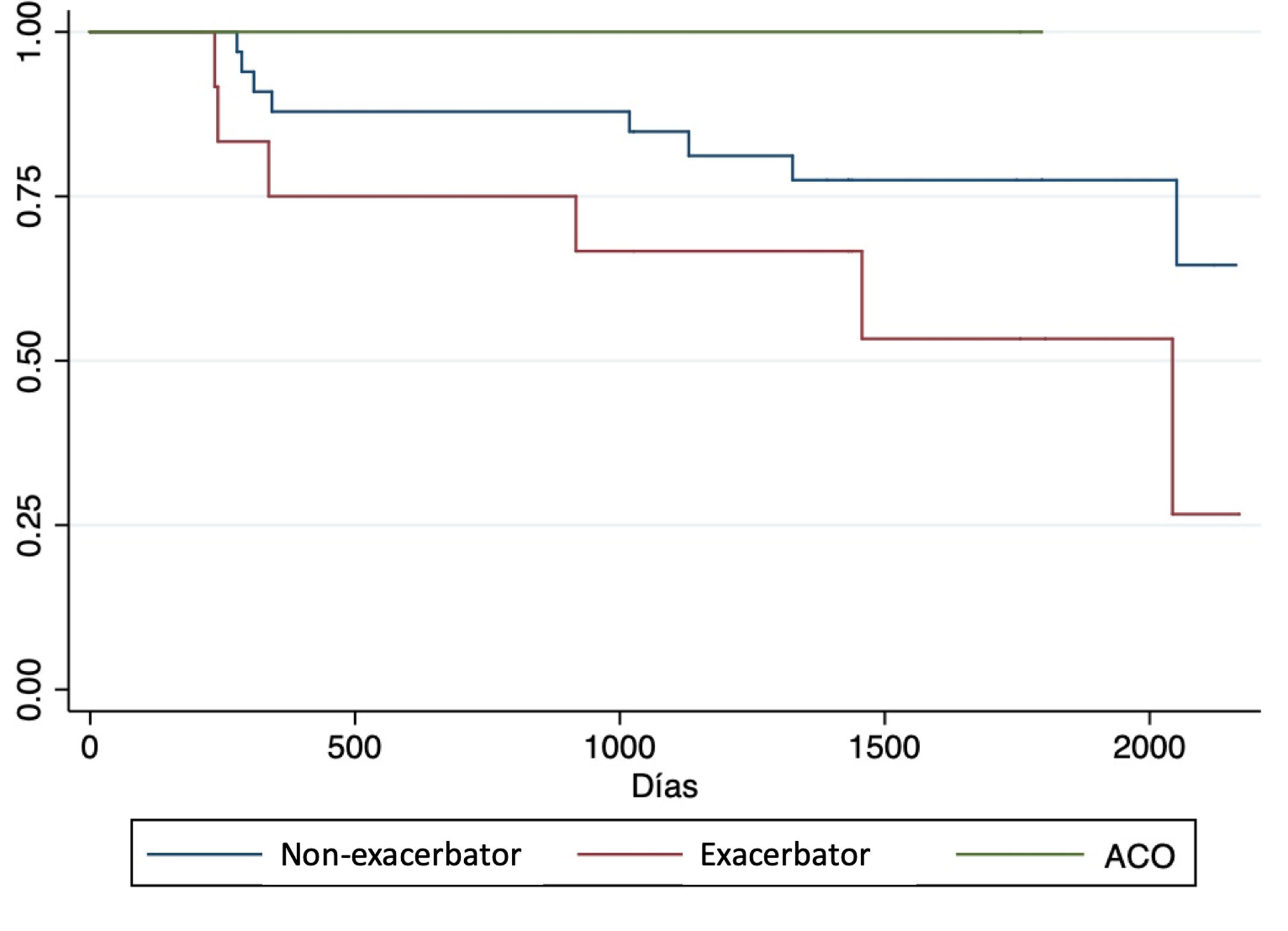

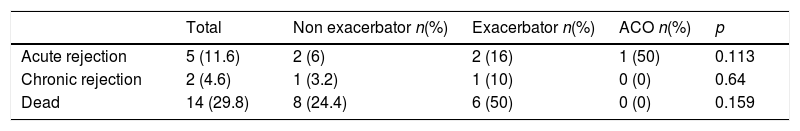

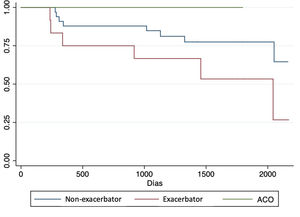

Complications and post-transplant evolutionWith a mean follow-up of 1365 (SD 580) days, we observed a higher non-significant incidence of acute rejection, chronic rejection and mortality in patients with exacerbator phenotype compared to the rest (Table 4). When analyzing survival curves based on their phenotype at the time of transplantation (Fig. 2), we observe that, once transplanted, the survival of patients with COPD turned out to be higher in patients with ACO phenotype (1432 days [SD 507.5]) followed by non-exacerbating patients (1317.8 days [SD 544.7]), and the exacerbating phenotype had the shortest post-transplant survival time (1115.1 days [SD 587]); although these differences did not reach statistical significance (p log Rank=0.16).

Complications and evolution of transplanted patients according to their COPD clinical phenotype. (ACO: asthma COPD overlap).

| Total | Non exacerbator n(%) | Exacerbator n(%) | ACO n(%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute rejection | 5 (11.6) | 2 (6) | 2 (16) | 1 (50) | 0.113 |

| Chronic rejection | 2 (4.6) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.64 |

| Dead | 14 (29.8) | 8 (24.4) | 6 (50) | 0 (0) | 0.159 |

The most COPD-phenotype evaluated for lung transplantation is the exacerbator, which is also the most likely to be discarded to be transplanted and, of those who are transplanted it is the one with the worst clinical evolution. Although this is not the first study that makes an assessment of patients with COPD referred for pulmonary transplant evaluation,15 it is the first one to date that has studied the prevalence of different COPD phenotypes among patients assessed and submitted for lung transplantation.

Real-life studies16 conducted in Central European population of patients seen in outpatient clinics establish that, unlike this work, where the exacerbator phenotype prevails, the majority of patients with COPD (63%) had a non-exacerbating phenotype, representing 30% exacerbator phenotype and 9.5% ACO. Specific studies from Spain show a lower prevalence of the exacerbator phenotype (around 20%) and a higher prevalence of the ACO phenotype (15.9%).17 Among the reasons that would justify this difference would be that the population referred for transplant, object of this study, is a more selected population, mostly in a terminal respiratory failure status and more fragile, being these patients the most susceptible to exacerbations and hospital admissions. Perhaps, the lack of differences in the baseline clinical and therapeutic characteristics of the patients assessed, unlike other published works,18 represents the uniformity in the extreme clinical severity of these patients, derived after having exhausted the different therapeutic possibilities.

International guidelines recommend referral for transplant evaluation to those patients where the disease is progressive despite maximum treatment that includes rehabilitation, has a BODE between 5 and 6, pCO2>50mmHg and/or pO2<60mmMg or FEV1<25%. On the other hand, they recommend accepting for transplantation and put the patient on the waiting list when one of the following criteria is met: BODE≥7, FEV1 between 15 and 20%, three or more severe exacerbations in the last year, an exacerbation with acute hypercapnia or the presence of pulmonary hypertension.9,19 Since this cohort presented an average BODE of 6.6 reflects an adequate reference to be assessed as potential transplant candidates.

Although the patients with exacerbator phenotype are the most referred, the final transplant rate is 12%, indicating that the vast majority of them were discarded for this procedure. Different studies have shown that these patients have a higher prevalence of cardiovascular pathology and other comorbidities such as depression, insomnia or anemia, compared to non-exacerbating phenotypes and ACO.20 We hypothesize that greater fragility21 and the presence of comorbidities could be reasons that have caused these patients to be finally ruled out. Another possibility is that they would have referred after a recent severe exacerbation without enough recovering after an adequate rehabilitation program. It has been described that hospitalizations induces a greater musculoskeletal weakness and worse functional situation22 related to different factors such as prolonged inactivity during it or systemic steroid treatments that are not uncommon to be used with doses above the recommended.23

Another finding of this work is that we have observed that the phenotype of the patient at the time of transplantation could influence survival and the development of subsequent complications. Thus, we have observed a tendency to higher post-transplant mortality in the exacerbator phenotype compared to the ACO and the non-exacerbator that would have superior survival. These results, although they did not acquire statistical differences, could be reflecting a greater degree of fragility of these patients. This situation could challenge the indications of the international guidelines, recommending to list the patient when they had 3 serious exacerbations,9 indicating that it may not take so long to do so, since the results could be worse. However we would like to highlight that this study was not designed or powered to look for survival, so this finding must be interpreted with caution and just as a potential hypothesis generator and in order to confirm it, it should be under a multicenter bigger study.

This work has a series of limitations that should be highlighted. The first is that the exacerbator phenotype is grouped as a single phenotype and no differentiation was made between chronic bronchitis and emphysema as recommended by some guidelines.10 The fact that the variable related to the presence of chronic bronchitis was not included in the protocol conditions this limitation. The low prescription of roflumilast and macrolide in these patients makes us hypothesize that emphysema predominated in the majority, although this fact has not been confirmed. Another limitation of the study is related to the definition of ACO employed. In this sense there has been a lot of controversy in recent years,24 and, while initially the diagnosis required some major and minor criteria (which included a history of asthma, lung function, bronchodilator test or atopy data), currently the most used criterion is the presence of a chronic obstruction not reversible to air flow in a non-smoking patient and with a history of asthma before the age of 40 years.10,14,25 On the other hand, we decided to exclude patients with alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency, since they present a series of slightly different clinical characteristics, as they use to be younger patients, with a greater degree of emphysema and with a different post-transplant evolution.14,26,27 When analyzing the results of post-transplant survival, it should be taken into account that it was not the main objective of this work, that the results were based on an univariate model and factors like mechanical ventilation, ischemia time, LAS index at the time of inclusion, etc., that could condition it were not studied. Finally, this is a study conducted in a single center, this determines the number of patients studied and transplanted in the study and on the other hand we cannot infer that these results are replicated in other cohorts. In this sense it would be interesting to compare these results with those presented in other transplant programs.

In summary, we can conclude based on our work that the COPD phenotype most valued for transplantation is the exacerbator, a phenotype that in approximately half of the cases does not complete the pre-transplant study and, among those who completed it, an important part do not get to transplant.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.