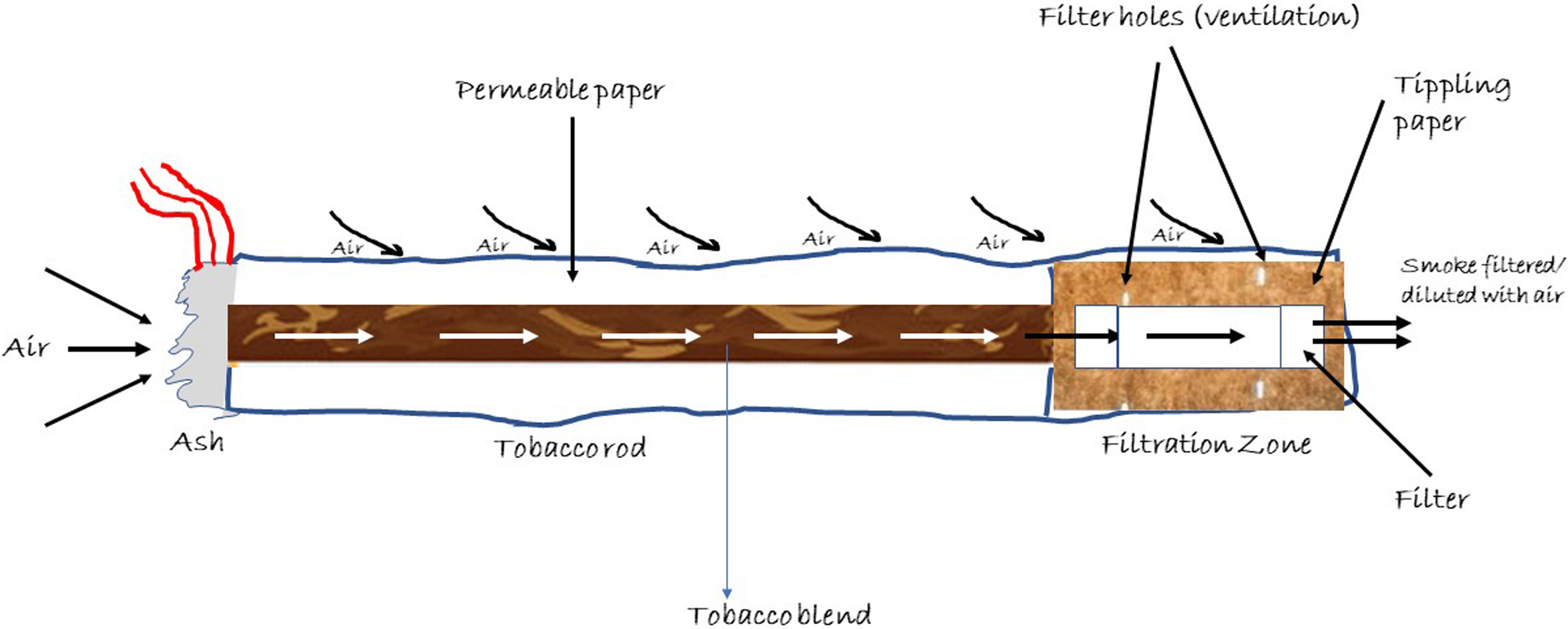

Epidemiological studies that associated tobacco use with lung cancer1 favoured addressing the modification of cigarette design.2 Since 1950, cigarettes have reduced the nicotine and tar content, as well as the content of other tobacco constituents. This reduction was produced by the incorporation of filters into cigarettes (with or without side holes), the selection of the type and variety of tobacco, the use of a more porous paper to wrap the tobacco in addition to the incorporation into the mixture of reconstituted tobacco (Fig. 1) and the use of cigarette smoking machine.2 Higher levels of citrate were added to cigarettes, which increased combustion and thus decreased the amount of polycyclic hydrocarbons carcinogens, but instead increased the formation of nitrosamines.2

Most cigarette filters are made from a non-biodegradable material.3 Although the filter has been understood as a barrier that wants to remove toxins, thus reducing damage, it is currently known that it does not offer health benefits to smokers, and inhalation of the fibers also affects them.4 Fragments of the material from which the filters are made are separated from it in manufacturing and are released on inhalation of the cigarette.5–7 Filter fibers have been found in the lungs of smokers with lung cancer.6 These modifications in cigarette design have also contributed to a change in the prevalence of the histological type of lung cancer, with adenocarcinoma now being the most frequent.4

Little by little over time, the percentage of filter cigarettes increased, reaching 97.5% in 1992.2 In the last 70 years, many materials have been patented to be used as cigarette filters, but the most used have been paper, charcoal and cellulose acetate, which is currently the most common.2

Charcoal filters (CF)Cigarettes with CF had little acceptance by consumers due to the sensory change they produced in the smoker.2 They were used to trap and remove carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, cyanide hydrogen, aldehydes, volatile carbonyls, acroleins, and free radicals.2 Pauly et al.5 investigated whether the CF contained carbon granules on the cut surface of the filter and whether these granules were released while smoking. The authors found charcoal granules in 79.8% of the cigarettes analysed, at a rate of 3.3 granules per cigarette and in all smokers the granules were released when smoked; well inhaled or ingested.

Cellulose acetate filters (CAF)CAF are made from cellulose that is acetylated (converted to cellulose acetate), and is dissolved, and spun as continuous synthetic fibers arranged in a bundle called tow, which is plasticized, shaped, and cut to a suitable length to act as a filter.2 These filters are a rod of 12,000 fibers and, fragments of this material, it is known, they separate from it in manufacturing and are released on inhalation of the cigarette.6,7 The efficiency of CAF to remove particles from cigarette smoke is substantially influenced by the length and circumference of the filter, the number and size of the filaments, and the presence of additives in the fibers.2 The selective lack of absorption of this CAF is known except for phenol, but instead they allow cyanide and hydrogen sulphide to pass.2 Again, Pauly et al.6,7 found that the CAF fibers and glass particles were released and therefore ingested or inhaled when cigarettes were smoked. These fibers were observed in histological samples from smokers with lung cancer.6 It is also known that fragments of cellulose acetate are separated from the filter of cigarettes when they are produced, as is the case with CAF, so they are defective, and should therefore be excluded from the production line, something that could also be detected by manufacturers and was known to them for more than 40 years, thus acting negligently.8

In the mid-1960s, the Surgeon General of the United States of America already considered cigarette filters useless to reduce harm to the smoker.9 In fact, epidemiological data collected between the 1970s and the early 2000s continued to support this conclusion: that the near-universal adoption of cigarette filters has done little to protect smokers.4 In 2011, a team of United States and Japan researchers stated that switching from unfiltered cigarettes to filter appears to have, like we have already said, simply altered the most common type of lung cancer, from squamous cell carcinoma to adenocarcinoma.10 Similarly, there is still no convincing evidence that cigarette filters have done anything to mitigate other risks to the smoker's health, such as heart and respiratory.9 A recent study11 indicate that filter ventilation alters tobacco combustion (with more smoke toxicants), get smoker to go deeper and inhale more smoke to maintain nicotine rate and causes a false perception of lower health risk. Authors suggests that filter ventilation has contributed clearly to the rise in lung adenocarcinomas among smokers and they concluded that as the Food and Drug Administration in the United States has now the authority to regulate cigarette design, they should consider regulating its use, up to and including a ban.11,12

On the other hand, and speaking about second hand smoking and under similar smoking conditions, filter-tipped cigarettes will have lower mainstream smoke yields than their untipped analogues,13 and it has been observed that his toxicity is not different in cigarettes with or without filters.14 Of course, sidestream smoke yields will not vary greatly, because they reflect the weight of tobacco burned during smouldering.13

Filters that are butts. Environmental pollutantButts (cigarette residues: filters), also called fourth-hand tobacco, constitute an important source of environmental pollutant since they contain toxins that can leak into the soil and water (pesticides, nicotine, cotinine, tar, carcinogens, metals, ethyl -phenol, ethylene glycol, menthol and rare earth elements, constituting the so-called emerging pollutants [which are already recognized as a global phenomenon]) characterized by their slow degradation.3,15

To conclude, there is evidence that cigarette filters do more harm than good. The side holes in filters cigarettes should probably be removed, which could reduce the use and toxicity of conventional cigarettes, and perhaps push smokers to consider quitting. Cigarettes have evolved over the past 70 years as an engineered product designed for inhalation, but the risk of becoming ill as a result of consumption has not changed.

Conflicts of interestAuthors declare they have no conflicts of interest.