The financial market has undergone numerous changes in recent years, becoming more competitive and characterized by offers of increasingly similar products and services by competitors. An alternative for companies to stand out in this market is the introduction of innovations and quality in services. This study proposes to evaluate the perceived quality of financial services by the members of a credit union. The study was conducted at a service unit of a credit union in Paraná State, Brazil. A survey with a sample of 167 members was applied, together with a questionnaire based on the SERVQUAL scale. The expectations and perceptions of the members were compared regarding the quality of services provided. An analysis of the responses enabled an evaluation of the gap between what members expect and what they perceive in terms of service quality. The main contribution of this article lies in the application of the SERVQUAL scale and the concepts of service quality in a cooperative organization in a sector that has been the focus of few academic studies. The results can be used to promote improvement processes in the services of the sector.

The globalized market means that modernizations increasingly have to deal with more opportunities and challenges. These can be due to demanding customers, fierce competition, diversified of supply or tumultuous economic scenarios. In this context, cooperatives emerge as a type of organization that, as a matter of principle, needs to strive for social development and at the same time remain economically competitive with organizations with market orientation (Meurer, Marcon, & Alberton, 2007).

The International Cooperative Alliance, at its conference in Manchester in September 1995, adopted a Statement on Cooperative Identity. This statement includes a list of the key values of the movement and a revised set of principles intended to guide cooperative organizations in the 21st century.

According to the Organization of Cooperatives in Brazil (OCB), the two major credit union systems are the Sicredi and the Sicoob (OCB, 2014). Together they have almost five million members, accounting for the fourth largest service network in the country. However, its main challenge is competitiveness, as credit unions compete with very strong public and private banks with greater market penetration. Moreover, financial products and services end up becoming commodities, and it is necessary to seek other differentials for an organization to strengthen its position in this highly competitive market.

Therefore, the drive for innovation and constantly increasing quality has become a fundamental condition for credit unions to grow and remain competitive. Seeking more practical and swifter forms of service has become an important competitive differential.

This scenario requires cooperatives to adopt a different stance that is mainly focused on the customer and service quality. Based on this, the present study seeks to evaluate the reflection of perceived service quality by members of a credit union through an innovation implemented in the service process. The aim of this innovation was a faster service and greater convenience for the members, enabling them to choose more segmented means of financial services in accordance with their needs.

For this purpose, this case study was divided into stages of research. First, a theoretical analysis was conducted on the topics of credit cooperativism, service innovation and service quality. This was followed by an analysis of the SERVQUAL scale created by Parasuraman, Berry, and Zeithaml (1985), and the Gaps model, as developed by Zeithaml, Parasuraman, and Berry (1990).

The main contribution of this study to the literature lies in the application of the concepts of innovation, service quality, the SERVQUAL scale and the concept of gaps in credit unions. This sector has been the focus of few academic studies.

Concerning the methodology, the study was conducted using a survey. To assess the internal consistency of the dimensions Cronbach's alpha was used. A bivariate analysis of disconfirmation was also used to identify and measure gaps between the items on the scales of perception and expectations. The studies related to the theory in question are presented in Parts One and Two of the article. In the third part, the research method is described, while the results are analyzed and discussed in the fourth section. In the final part, the conclusions are given regarding the results.

Literature reviewCredit unionismThe first credit unions were organized in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, mainly in Germany and Italy. However, the major impact in the development of the cooperative movement and the emergence of cooperatives around the world stemmed from the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society Limited, founded in the north of England in 1844 by 28 workers from different professions. Their goal was to create a self-sufficient colony and support other entities with this purpose (Mendes, 2010).

According to the SESCOOP (2013), the cooperative principles were created by cooperative leaders and thinkers based on cooperation, in keeping with the first formal cooperative, the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers. Nevertheless, as the movement evolved, the cooperative principles were revised.

In Brazil, the movement began with the creation of the first consumer cooperative registered in Brazil, in Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais State in 1889. The entity was named the Economic Cooperative Society of Public Sector Workers of Ouro Preto (Sociedade Cooperativa Econômica dos Funcionários Públicos de Ouro Preto). It then spread to other states. In 1902, the first credit union in Brazil was created in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. This was the initiative of a Swiss priest, Theodor Amstadt. Beginning in 1906, rural cooperatives were created and developed, as envisioned by farmers (OCB, 2014).

In 1971, Law 5.764 was promulgated. This law regulates Brazilian cooperativism until today. It also regulated the Organization of Cooperatives in Brazil (OCB), the main representative of Brazilian cooperatives (OCB, 2014). Later, Complementary Law 130 was passed, which regulated the National Credit Union System, in accordance with Article 192 of the Federal Constitution of 1988. This provided legal stability to the model of credit cooperativism that had been adopted in the country (Saraiva & Crubelatte, 2012).

Credit unions are agencies that basically provide the same services as banks. However, they have a characteristic that differentiates them from other financial institutions: their customers, in addition to using the products, have a share in the institutional capital of the cooperative, making them “members. This peculiarity is considered the main difference between credit unions and banks (Silva & Bacha, 2007).

According to Barroso and Bialoskorski Neto (2012), in cooperative organizations, operational surpluses from the activities of the cooperative members are known as “profits” and are made available at the end of each financial year to the general assembly to decide what should be done with them. Commercial banks, in turn, are financial institutions whose main objective is financing economic activity in the short and long term. Banks are for-profit companies, and can be controlled by a government agency (federal or state government) or be in the private sector (Silva & Bacha, 2007).

A fundamental aspect that cooperatives should be concerned with is the satisfaction of their “customers”, as customer loyalty is fundamental for the good performance of the organization. In a cooperative, a member is also a customer (Mendes, 2010).

Raimundo (2010) remarks that, due to the fierce competition between organizations, there has been a considerable growth in the offer of products and services. This has made customers increasingly demanding of the organizations and their professionals, singular characteristics when it comes to meeting the different wishes and needs of their target public. Thus, companies need to innovate constantly, adding value to their products and services, adapting and creating new strategies, creating new products and identifying new opportunities.

The cooperative doctrine has more advantages than problems, and its principles can indeed lead to greater competitiveness. The author understands that the relationship of commitment between the cooperative and its members cannot be based only on the strength of the statute and must be built on the trust that the cooperative will meet the needs of members. Only then can there be effective loyalty (Mendes, 2010).

This understanding is also emphasized by Maciel and Castro (2010), who claim that focused innovations such as market strategy must have a close relationship to the customer, and there should always be an effort to identify the customer's needs. The ability to innovate is one of the key factors for success in an organization. This also applies directly to the success of credit unions.

Service InnovationAccording to Tidd, Bessant, and Pavitt (2008), there is agreement on a basic innovation structure and that an adequate balance between simplification and representation is required. In general, the managerial models available for innovation concentrate on product development, with few considerations on underlying activities, even though these activities are no less important to the process of creating innovations.

Innovation as the object of academic research has been studied mainly in the tangible goods industry and is based on the empirical reality of this economic sector in which innovation theory has developed and grown in volume in recent decades. The study of innovation in the intangible goods industry, i.e., the service sector, is characterized by a very different situation. The literature on service innovation emerged in the 1990s (Morrar, 2014), based on the assumption that service providers also innovate and that to understand this phenomenon the field has attempted to develop theoretical models of its own to enable service innovation to be analyzed without the bias of the hegemonic innovation theories with a predominantly industrial empirical basis.

Service innovationServices involve a form of contracting through which consumers can obtain benefits. Customers value desired experiences and solutions and are willing to pay for them (Lovelock, Wirtz, & Hemzo, 2011).

In the last decades of the twentieth century, many companies began to invest in and promote service quality with a view to achieving differentiation and building competitive advantages (Zeithaml, Bitner, & Gremler, 2014). An examination of the past shows that technology was the main driving force behind innovations in services that are viewed as natural today. More recently, the Internet has grown immensely and has brought in its wake a wide array of new services.

To Zeithaml et al. (2014), one of the basic concepts of marketing is the 4 Ps marketing mix, defined as the elements controlled by an organization and used to serve or communicate with customers. The notion of mix means that all the variables are related and are dependent on one another to a certain extent. However, the strategies for the 4 Ps require modification whenever they are applied to services. Recognizing the importance of additional variables led marketing professionals to adopt the mix with an expansion of the marketing of services, adding three new Ps: process, physical environment and people and thereby forming the 7 Ps of service marketing (Lovelock et al., 2011).

Gallouj and Savona (2010) highlight that in the field of service innovation there are fewer theoretical than empirical contributions. These contributions, as proposed by Vence and Trigo (2010), can be clustered into three groups: the assimilation perspective (innovation in services perceived in the same way as innovation in manufacturing), the demarcation approach (concentrating attention on organizational innovation and service innovation for knowledge-based businesses) and the synthesis perspective (suggesting that services and manufacturing activities are interrelated).

Different types of changes in the characteristics of services result in different innovation models. These can be radical, improvement, incremental or recombination innovation models. Radical innovation is the creation of a new set of characteristics for a totally new service (Djellal, Gallouj, & Miles, 2013; Gallouj & Weinstein, 1997). Improvement innovation means greater emphasis on certain characteristics without changing the system of competences and the value of certain characteristics of the service (Tuschman & Anderson, 1986). Incremental innovation means adding, eliminating or substituting characteristics. The general structure of the system remains the same, but the system is marginally changed by adding new elements (Djellal et al., 2013; Gallouj & Weinstein, 1997). The fourth type of innovation, recombination innovation, is one of the main forms of innovation based on the principles of association and disassociation of the technical and final characteristics of the service. This type of innovation is based on the addition of characteristics, especially when the additional characteristics originated in pre-existing services. Recombination innovation can also emerge as the implementation of a new technology, such as the use of a new medium, to provide a new information service (Djellal et al., 2013; Gallouj & Weinstein, 1997).

Lovelock and Wright (2001) claim that the customer's degree of involvement is often determined more by tradition and a desire to meet the service provider personally than the needs of the operational process. In this context, the relevance of service quality is perceived.

Service qualityPaladini (2011) understands that the fact that the term quality is commonly used may result from the considerable efforts made in the recent past to popularize the term. In his understanding, this cannot be said to be a bad thing. The problem lies in the frequent use of incorrect concepts. This is because something that is already widely known cannot be intuitively redefined; nor can the term be restricted to specific situations, as it is in the public domain.

Service quality management involved highly subjective assessment processes. The appreciation of variables in service provision requires measurement scales and tools capable of measuring perceptions and expectations with a reasonable degree of objectivity. An accurate evaluation of an external service aids companies to reposition themselves in the market and redirect their resources to achieve service quality levels compatible with customers’ needs (Pereira Filho, Campos, & Nóbrea, 2015).

Customer expectations are the real standards for service quality assessment. Berry and Parasuraman (1992), based on the result of research in several sectors, claim that customers assess quality by comparing what they desire or expect with what they experience. Perceived quality is the relationship between a customer's expectation and perception. Thus, it can be said that satisfaction will exist when perception is greater than expectation, with dissatisfaction being the opposite result (Carpinetti, 2011).

In the absence of objective measurements, an appropriate approach to measuring service quality is to measure the difference between consumers’ expectations and perception of company performance, i.e., perceived quality (Parasuraman et al., 1985). To Zeithaml et al. (1990), the main aspects considered by consumers regarding service quality are tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy.

An important factor is how to measure the quality of services offered by an organization. For this study, the model of the SERVQUAL scale was used.

SERVQUAL scaleSince its introduction, SERVQUAL has been widely used and studied in the service quality literature, demonstrating its importance. Studies using SERVQUAL, either directly or with small changes, have been conducted by numerous researchers (Berlezzi & Zilber, 2011).

SERVQUAL is a scale developed to measure the difference between customers’ expectations and perception of a service. It is based on the view that customer assessment is of great importance. This evaluation is conceived as a gap between a customer's expectations and evaluation of a service provider's performance. In its original formulation, Parasuraman et al. (1985) identified ten components: reliability; responsiveness; competence; access; courtesy; communication; credibility; security; knowing the customer and; tangibles.

According to Berlezzi and Zilber (2011), following successive applications and statistical analyses, the Servqual scale was improved. The ten dimensions were reduced to only five. Tangibles, reliability and responsiveness remained as originally conceived. Competence, courtesy, credibility and security were combined into a single dimension: assurance. The others (accessibility, communication and knowing the customer) were placed in a new dimension: empathy, with the five dimensions as follows:

- •

Tangibles: appearance of physical installations, buildings, equipment, staff and communication materials.

- •

Reliability: ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately.

- •

Responsiveness: willingness to serve the customer and provide prompt service.

- •

Assurance: knowledge and courtesy of employees and ability to convey confidence and trust.

- •

Empathy: providing caring individualized attention to customers.

Parasuraman et al. (1985) then developed a 22-item instrument for measuring the expectations and perception of customers. The instrument is administered twice in different forms. The first is to measure expectations and the second to measure perception.

From the exploratory study, Zeithaml et al. (1990) reached the conclusion that discrepancies can occur between customers’ expectations of services provided and their perception of them. This gap is the result of a series of four types of gap in internal interfaces, which represent the side of the company on the one hand and the external interfaces as seen by the customer on the other. More directly, the authors represent these types of gaps in five propositions, whose final impact results in the distance between customer expectations of the services that a company offers and the services that they feel are actually delivered.

According to these authors, customers evaluate service quality by comparing what they desire or expect with what is actually delivered. The evaluation criteria take into account the gaps. These are the differences between consumer expectations and actual delivery. These gaps are large obstacles to be faced in the attempt to achieve a level of excellence in service delivery:

- •

Gap 1=Gap between consumer expectation and management perception regarding these expectations.

- •

Gap 2=Gap between management perception of customer expectations and service quality specification.

- •

Gap 3=Gap between service quality specification and actual service delivery.

- •

Gap 4=Gap between services offered and external communication to the customer.

- •

Gap 5=Gap between service expected by the customer and his perception of the service provided.

The case study was used as a research strategy. According to Yin (2001), it is ideal for real organizational situations in which the researcher has no control over the phenomena. As it is a case study, a limitation on the research is the difficulty in generalizing the results. However, as observed by Yin (2001, p. 29), “the case study, like the experiment, does not represent a ‘sample’, and the investigator's goal is to expand and generalize theories (analytic generalization) and not to enumerate frequencies (statistical generalization)”. The case in question is a credit union, chosen because it is characteristic of this sector. Data triangulation was done using internal secondary data and the primary data were collected from the credit union members and through observation by the researchers.

The primary data were collected using a survey. The results were derived from the questionnaire applied to a sample composed of members at the service unit of a credit union. The sample population was made up of a set of members at this unit, totaling 3500 people. The sample size was 167 members. The data were collected using the questionnaire over a period of twenty days in the month of June 2014 either in person at the unit or by telephone via telemarketing. The questionnaires were based on the previously described SERVQUAL model, adapted from Rocha and Oliveira (2003). The questionnaire contained 44 sentences with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) I totally disagree to (5) I fully agree.

Authors such as Mattar (2014) and Malhotra (2012) claim that the Likert scale, as an ordinal scale, is not suitable for reaching conclusions on the meaning of the distances between positions on the scales. Therefore, it is important to conduct non-parametric tests. Furthermore, they claim that in ordinal scales, the only measurements of central tendency that can be calculated are the mode and median. A peculiarity of ordinal data is that the mean and standard deviation cannot be calculated. Some software may allow the calculation, but the values are doubtful, as can be seen in Freund (2006, p. 21). However, the scale is often used in marketing as an interval scale, thus allowing parametric analyses of its original data. Doane and Seward (2014) claim that the Likert scale can be considered as a special case of interval scale. Verbal anchors such as “I totally disagree” and “I fully agree” are used, allowing the interviewee to choose a point in a numerical interval between two extremes, eliminating the problem between the distances between points. This scale model with verbal anchors and unlabeled numerical intervals was used for this study, enabling the use of parametric statistics. The sentences were divided into two 22-item blocks: expectations and perceptions, respectively.

To evaluate the internal consistency of the dimensions (expectation and perception), Cronbach's alpha was used. The α index estimates how evenly the items contribute to the unweighted sum of the instrument, varying on a scale of 0 to 1. It is known for the internal consistency of the scale and thus α can be interpreted as the average coefficient of all the estimates of internal consistency that would be obtained if all the possible scale divisions were made (Cronbach, 1951).

In the last 50 years, Cronbach's alpha has been used as the function that psychometricians have sought since the earliest works of Spearman and Brown for a valid measurement of internal consistency, and it is the quintessential tool for measuring consistency (Maroco & Garcia-Marques, 2013).

In general, an instrument or test is classified as reliable when the α is at least 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978). However, in some scenarios of social science research, an α of 0.60 is deemed acceptable, providing the results obtained are interpreted with caution and take into consideration the computational context of the index (DeVellis, 1991).

The results obtained were 0.95 for the expectation dimensions and 0.95 for perception, considering all the clustered dimensions. When the alpha was calculated for each dimension, we had the following results: tangibles (0.90), reliability (0.94), responsiveness (0.92), assurance (0.93) and empathy (0.94). According to Churchill (1995), values higher than 0.60 are considered satisfactory, which is the case of the present study. Therefore, it can be concluded that the scale has good internal consistency.

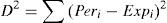

The analyses of the 22 responses to the questionnaire were conducted by calculating the averages, standard deviations, gaps between perception and expectation and a bivariate analysis of disconfirmations. The bivariate analysis was conducted to identify and measure the gaps between the items on the perception and expectation scales. An effort was made to apply the Disconfirmation Paradigm, in accordance with Lewis and Booms (1983). The statistical resource was the Quadratic Euclidean Distance (Cronbach & Glesser, 1953), calculated using the following equation.

where Peri – is an item of the Perception scale; Expi – represents the same item on the Expectation scale.According to Parasuraman et al. (1985), disconfirmations or gaps can represent the strong or weak points of a company, depending on whether respondents’ perceptions are better or worse than expected. However, the disconfirmations that are calculated, despite showing values for the Quadratic Euclidean Distances between the scales, do not show whether an incongruence is a strong or weak point, as they assume only positive values or a value equal to zero. Therefore, it was decided that the sum of the scores attributed to the items on the two scales would also be used to observe whether the disconfirmation was a strong or weak point for each item in question.

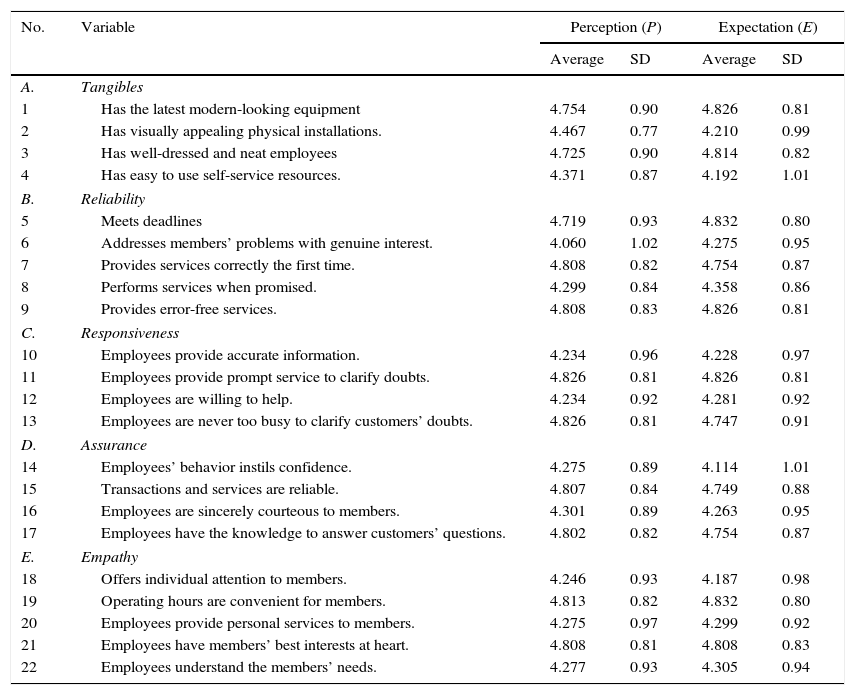

Analysis and discussion of the resultsTable 1 shows the averages and standard deviations of the variables on the perception and expectation scales. The standard deviation was used to evaluate whether the responses varied greatly.

Averages and standard deviations of the expectation and perception scales.

| No. | Variable | Perception (P) | Expectation (E) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | SD | Average | SD | ||

| A. | Tangibles | ||||

| 1 | Has the latest modern-looking equipment | 4.754 | 0.90 | 4.826 | 0.81 |

| 2 | Has visually appealing physical installations. | 4.467 | 0.77 | 4.210 | 0.99 |

| 3 | Has well-dressed and neat employees | 4.725 | 0.90 | 4.814 | 0.82 |

| 4 | Has easy to use self-service resources. | 4.371 | 0.87 | 4.192 | 1.01 |

| B. | Reliability | ||||

| 5 | Meets deadlines | 4.719 | 0.93 | 4.832 | 0.80 |

| 6 | Addresses members’ problems with genuine interest. | 4.060 | 1.02 | 4.275 | 0.95 |

| 7 | Provides services correctly the first time. | 4.808 | 0.82 | 4.754 | 0.87 |

| 8 | Performs services when promised. | 4.299 | 0.84 | 4.358 | 0.86 |

| 9 | Provides error-free services. | 4.808 | 0.83 | 4.826 | 0.81 |

| C. | Responsiveness | ||||

| 10 | Employees provide accurate information. | 4.234 | 0.96 | 4.228 | 0.97 |

| 11 | Employees provide prompt service to clarify doubts. | 4.826 | 0.81 | 4.826 | 0.81 |

| 12 | Employees are willing to help. | 4.234 | 0.92 | 4.281 | 0.92 |

| 13 | Employees are never too busy to clarify customers’ doubts. | 4.826 | 0.81 | 4.747 | 0.91 |

| D. | Assurance | ||||

| 14 | Employees’ behavior instils confidence. | 4.275 | 0.89 | 4.114 | 1.01 |

| 15 | Transactions and services are reliable. | 4.807 | 0.84 | 4.749 | 0.88 |

| 16 | Employees are sincerely courteous to members. | 4.301 | 0.89 | 4.263 | 0.95 |

| 17 | Employees have the knowledge to answer customers’ questions. | 4.802 | 0.82 | 4.754 | 0.87 |

| E. | Empathy | ||||

| 18 | Offers individual attention to members. | 4.246 | 0.93 | 4.187 | 0.98 |

| 19 | Operating hours are convenient for members. | 4.813 | 0.82 | 4.832 | 0.80 |

| 20 | Employees provide personal services to members. | 4.275 | 0.97 | 4.299 | 0.92 |

| 21 | Employees have members’ best interests at heart. | 4.808 | 0.81 | 4.808 | 0.83 |

| 22 | Employees understand the members’ needs. | 4.277 | 0.93 | 4.305 | 0.94 |

Concerning the perception scale, two of the three highest averages are found in the Responsiveness variable, items “Employees provide prompt service to clarify doubts” (4.826) and “Employees are never too busy to clarify customers’ doubts” (4.826). The third highest average was found in the Empathy Variable, the item “Operating hours are convenient for members” (4.813). These three items have very close meanings, as they are linked to service and availability. As for the standard deviation, the scores (0.81, 0.91 and 0.80, respectively) vary slightly between the first and third item, while the second has a somewhat higher variation.

Regarding the highest averages of the perception scale, the following items stand out: “Provides services correctly the first time” (4.808), “Provides error-free services” (4.808) “Employees have members’ best interests at heart” (4.808), and “Transactions and services are reliable” (4.807). The standard deviations of these variables, respectively, were 0.87, 0.81, 0.83 and 0.88. The slight variation between the items shows that the interviewees believe that the credit union offers quality service, with the highest averages relative to responsiveness, empathy and reliability, showing that the union has employees that serve its members well and the members trust the institution.

The lowest averages are for the items “Addresses members’ problems with genuine interest” (4.060), “Employees provide accurate information” (4.234) and “Employees are willing to help” (4.234). It should be highlighted that two of the highest and two of the lowest averages are for Responsiveness, which may mean that the attention and service of employees at the units are unequal. The credit union should do further individual analyses of the data, i.e., verify the averages of each unit separately to identify variations between them and take the necessary measures to address them.

The highest standard deviations for perception were “Addresses members’ problems with genuine interest” (1.02) and “Employees provide accurate information” (0.96), emphasizing the need for the credit union to assess each unit individually.

Regarding the expectation scale, the three highest averages were “Meets deadlines” (4.832), “Operating hours are convenient for members” (4.832) and, with (4.826) “Has the latest modern-looking equipment”, “Provides error-free services” and “Employees provide prompt service to clarify doubts”. These are the items the interviewees consider most important.

Only the item “Employees provide prompt service to clarify doubts” has the same average for perception and expectation, i.e., in this item, the credit union has lived up to the expectations of the interviewees. The other items with the highest averages on the expectation scale had lower averages than on the perception scale, showing that the interviewees expect more from the union in these cases.

The lowest score was “Employees’ behavior instils confidence” (4.114). The second and third lowest were “Offers individual attention to members” (4.187) and “Has easy to use self-service resources” (4.192). These were viewed as the least important by the interviewees.

The highest standard deviations on the expectation scale were “Has easy to use self-service resources” and “Employees’ behavior instils confidence”, both of which were (1.01). The third highest was “Has visually appealing physical installations” (0.99). These three items are different from those with the highest averages on the expectation scale.

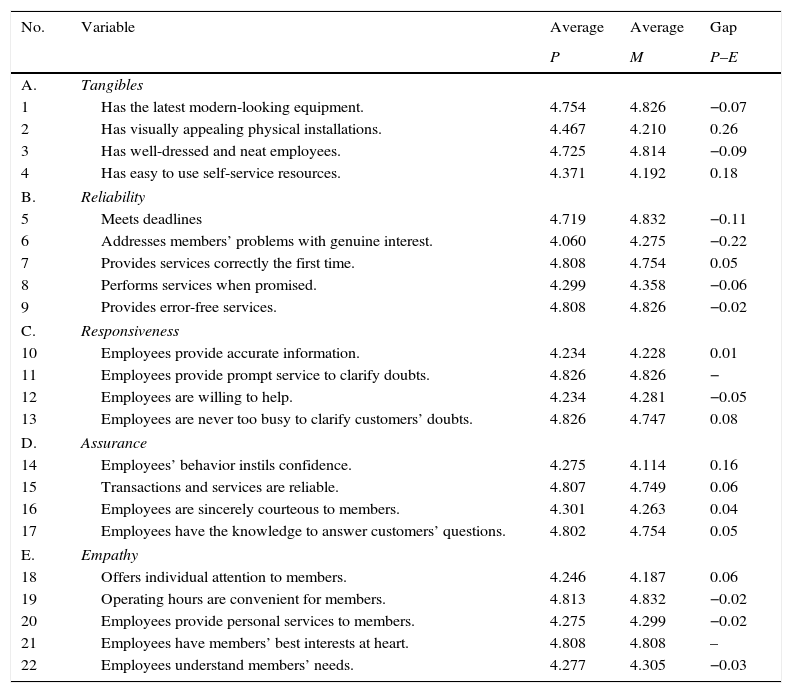

Table 2 shows a comparison of the measurements of the perception and expectation scales through the gaps created between them in the responses. The largest positive gaps, i.e., where perception is greater than expectation, are “Has visually appealing physical installations” (0.26), “Has easy to use self-service resources” (0.18) and “Employees’ behavior instils confidence” (0.16). In these cases, the union surpassed the expectations of its members.

Comparison of the averages of perception and expectation (gap).

| No. | Variable | Average | Average | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | M | P–E | ||

| A. | Tangibles | |||

| 1 | Has the latest modern-looking equipment. | 4.754 | 4.826 | −0.07 |

| 2 | Has visually appealing physical installations. | 4.467 | 4.210 | 0.26 |

| 3 | Has well-dressed and neat employees. | 4.725 | 4.814 | −0.09 |

| 4 | Has easy to use self-service resources. | 4.371 | 4.192 | 0.18 |

| B. | Reliability | |||

| 5 | Meets deadlines | 4.719 | 4.832 | −0.11 |

| 6 | Addresses members’ problems with genuine interest. | 4.060 | 4.275 | −0.22 |

| 7 | Provides services correctly the first time. | 4.808 | 4.754 | 0.05 |

| 8 | Performs services when promised. | 4.299 | 4.358 | −0.06 |

| 9 | Provides error-free services. | 4.808 | 4.826 | −0.02 |

| C. | Responsiveness | |||

| 10 | Employees provide accurate information. | 4.234 | 4.228 | 0.01 |

| 11 | Employees provide prompt service to clarify doubts. | 4.826 | 4.826 | − |

| 12 | Employees are willing to help. | 4.234 | 4.281 | −0.05 |

| 13 | Employees are never too busy to clarify customers’ doubts. | 4.826 | 4.747 | 0.08 |

| D. | Assurance | |||

| 14 | Employees’ behavior instils confidence. | 4.275 | 4.114 | 0.16 |

| 15 | Transactions and services are reliable. | 4.807 | 4.749 | 0.06 |

| 16 | Employees are sincerely courteous to members. | 4.301 | 4.263 | 0.04 |

| 17 | Employees have the knowledge to answer customers’ questions. | 4.802 | 4.754 | 0.05 |

| E. | Empathy | |||

| 18 | Offers individual attention to members. | 4.246 | 4.187 | 0.06 |

| 19 | Operating hours are convenient for members. | 4.813 | 4.832 | −0.02 |

| 20 | Employees provide personal services to members. | 4.275 | 4.299 | −0.02 |

| 21 | Employees have members’ best interests at heart. | 4.808 | 4.808 | – |

| 22 | Employees understand members’ needs. | 4.277 | 4.305 | −0.03 |

It should also be noted that the items “Employees are never too busy to clarify doubts” (0.08), “Offers individual attention to members” (0.06), “Transactions and services are reliable” (0.06), “Provides services correctly the first time” (0.05), “Employees have the knowledge to answer customers’ questions” (0.05), “Employees are sincerely courteous to members” (0.04) and “Employees provide accurate information” (0.01) all had a positive gap, i.e., the members believe that the credit union has delivered more than they expected. It should also be highlighted that “Employees provide prompt service to clarify doubts” had a gap equal to zero, i.e., in this case the credit union also lives up to the interviewees’ expectations.

The items “Addresses members’ problems with genuine interest” (−0.22), “Meets deadlines” (−0.11), “Has well-dressed and neat employees” (−0.09), “Has the latest modern-looking equipment” (−0.07), “Performs services when promised” (−0.06), “Employees are willing to help” (−0.05), “Employees understand the members’ needs” (−0.03), “Operating hours are convenient for members” (−0.02) and “Offers individual attention to members” (−0.02) had a negative gap. In other words, in the opinion of the respondents’ the delivery of these items is less effective than expected. These results can help the credit union to analyze each item with a negative gap, understand the factors that contribute to the delivery of the service falling short of expectations and attempt to improve them for a better perception in future research.

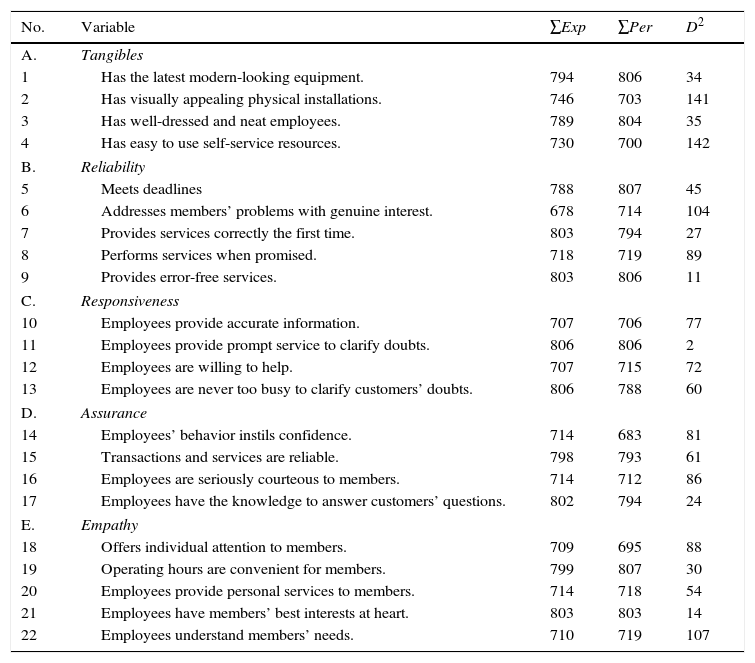

Disconfirmation between the perception and expectation scalesTable 3 shows the values of the disconfirmations between the perception and expectation scales (D2), calculated in accordance with Eq. (1), and the sums of the responses for expectation and perception.

Total disconfirmation and sums of responses.

| No. | Variable | ∑Exp | ∑Per | D2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. | Tangibles | |||

| 1 | Has the latest modern-looking equipment. | 794 | 806 | 34 |

| 2 | Has visually appealing physical installations. | 746 | 703 | 141 |

| 3 | Has well-dressed and neat employees. | 789 | 804 | 35 |

| 4 | Has easy to use self-service resources. | 730 | 700 | 142 |

| B. | Reliability | |||

| 5 | Meets deadlines | 788 | 807 | 45 |

| 6 | Addresses members’ problems with genuine interest. | 678 | 714 | 104 |

| 7 | Provides services correctly the first time. | 803 | 794 | 27 |

| 8 | Performs services when promised. | 718 | 719 | 89 |

| 9 | Provides error-free services. | 803 | 806 | 11 |

| C. | Responsiveness | |||

| 10 | Employees provide accurate information. | 707 | 706 | 77 |

| 11 | Employees provide prompt service to clarify doubts. | 806 | 806 | 2 |

| 12 | Employees are willing to help. | 707 | 715 | 72 |

| 13 | Employees are never too busy to clarify customers’ doubts. | 806 | 788 | 60 |

| D. | Assurance | |||

| 14 | Employees’ behavior instils confidence. | 714 | 683 | 81 |

| 15 | Transactions and services are reliable. | 798 | 793 | 61 |

| 16 | Employees are seriously courteous to members. | 714 | 712 | 86 |

| 17 | Employees have the knowledge to answer customers’ questions. | 802 | 794 | 24 |

| E. | Empathy | |||

| 18 | Offers individual attention to members. | 709 | 695 | 88 |

| 19 | Operating hours are convenient for members. | 799 | 807 | 30 |

| 20 | Employees provide personal services to members. | 714 | 718 | 54 |

| 21 | Employees have members’ best interests at heart. | 803 | 803 | 14 |

| 22 | Employees understand members’ needs. | 710 | 719 | 107 |

The lowest disconfirmation was for: “Employees provide prompt service to clarify doubts” (2), “Provides error-free services” (11), “Employees have members’ best interests at heart” (14), “Employees have the knowledge to answer customers’ questions” (24) and “Provides services correctly the first time” (27). This strengthens the earlier statement that the credit union has good service delivery in terms of clarifying doubts or providing error-free services, thanks to the good knowledge of its employees. Another important point was the employees having members’ interests at heart, which is essential to a cooperative organization.

However, some points also appear again among the highest disconfirmations: “Employees understand members’ needs” (107) and “Addresses members’ problems with genuine interest” (104). These items require the most urgent attention from the managers of the credit union regarding the work of their employees. Another important point for improvement was “Performs services when promised” (89). The union needs to take action to address problems by getting back to the members and keeping to deadlines.

There are lower dissimilarities in the items “Employees provide prompt service to clarify doubts” (2), “Provides error-free services” (11), “Employees have members’ best interests at heart” (14), “Employees have the knowledge to answer customers’ questions” (24) and “Provides services correctly the first time” (27). This reinforces what was seen above, that the credit union delivers its services well when it comes to clearing up doubts and providing error-free services thanks to its employees’ knowledge. Another important point was having the members’ interests at heart, which is prudent for a cooperative organization.

Nevertheless, the data show that some points emerge again among the greatest dissimilarities: “Employees understand the members’ needs” (107) and “Addresses members’ problems with genuine interest” (104). The latter was most frequently identified as an aspect for the union to develop. It requires the special attention of the managers when instructing their employees. Furthermore, “Performs services when promised” (89) is another item that appeared several times as a point for development. The credit union needs to develop important work regarding how it addresses problems and gets back to its members, respecting deadlines.

For an analysis of the disconfirmations, it is of fundamental importance to pay individual attention to the value identified in the two scales, and not only the presented scores. For a more accurate analysis, it is first necessary to consider the results of the expectation scale. This is because a low result in this case may show that a variable is of little importance to the interviewee. For instance, the variable “Employees provide prompt service to clarify doubts”, despite having the lowest disconfirmation value in the table (2), had higher values of expectation and perception than those of the variable “Has visually appealing physical installations”, which had lower values for perception and expectation, but the highest disconfirmation in the table (141).

ConclusionThe evaluation of service quality showed efforts made by the credit union to meet the expectations of its members in terms of physical installations, self-service resources and employee behavior, which had higher averages than expected. The union can strengthen these points further, as they are important differentials in the market.

It was of great interest that two of the highest and two of the lowest averages were found in the responsiveness variable. This might suggest uneven attention and service by employees at the units under study. The credit union should conduct a further analysis in this respect, assessing the individual data, i.e., analyzing the averages of each unit separately. Thus, it will be possible to identify variations between the units and take the necessary steps to address them.

Regarding members’ problems, delivery deadlines, employees’ attire, equipment, willingness to employees to help and convenient times, the credit union needs to pay greater attention to these points, as in the study they had below average expectations. The members expect more from these services.

It also falls to the credit union to evaluate better the question of “addressing members’ problems with genuine interest”. This item may represent discontent among members whenever they feel that the employees are not giving them due attention. The credit union should discuss internally with its employees the difference between “good friendly service with a smile” and actual good service, which means attending to members’ needs.

The main contribution of the study to the literature was the application of the SERVQUAL scale of Parasuraman et al. (1985) at a credit union, as this sector is lacking in academic studies. Thus, the model constitutes a starting point for conducting confirmatory studies on proposed value in financial institutions, especially credit unions.

To take greater advantage of the study, it is suggested that the union, after a certain time, should redo the research, measuring the items again to see whether there has been a change in the perceived quality by members due actions taken as a result of this study.

The disadvantages of the model lie in the questionnaire having only closed questions, precluding the users from expressing opinions, criticisms or suggestion and limiting the study to quantitative data. To minimize this problem, it is suggested that at least one open question should be included to enable comments, suggestions and criticisms.

A suggestion for future works is the use of a larger sample with public and private financial institutions and other credit unions to gauge significant differences. Finally, the existence of other models in the literature to evaluate service quality is another research possibility, as different models can be applied to the financial institution segment to discover which model is the most appropriate.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Departamento de Administração, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo – FEA/USP.