The present study evaluates the effects of vaccination with Brucella melitensis strains Rev 1 ΔeryCD and Rev 1 on the reproductive system of male goats. Three groups, each of them consisting of 15 six-month-old brucellosis-free male goats, were studied. The first group was vaccinated with the Rev 1 ΔeryCD strain, the second group received Rev 1 and the third group was inoculated with sterile physiological saline solution. The dose of both strains was of 1×109CFU/ml. Over the course of the five months of this study, three males from each group were euthanized every month. Their reproductive tracts, spleens, and lymph nodes were collected to analyze serology, bacteriology PCR, histology, and immunohistochemistry. Results show that vaccination with B. melitensis strains Rev 1 ΔeryCD and Rev 1 does not harm the reproductive system of male goats. Strain B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD displayed a lower capacity to colonize the reproductive tract than strain Rev 1, which was attributed to its limited catabolic action toward erythritol.

La presente investigación evalúa los efectos de la vacunación con Brucella melitensis cepas Rev 1 ΔeryCD y Rev 1 en el sistema reproductivo de machos caprinos. Se estudiaron tres grupos de caprinos, integrado cada grupo por 15 machos libres de brucelosis de seis meses de edad. El primer grupo fue vacunado con la cepa Rev 1 ΔeryCD, el segundo grupo recibió Rev 1 y el tercer grupo recibió solución salina fisiológica estéril (control). El título de las dos cepas inoculadas fue de 1×109UFC/ml. Tres machos de cada grupo fueron sacrificados cada mes durante los cinco meses de este estudio. Se recolectaron el tracto reproductivo, el bazo y los ganglios linfáticos para análisis de serología, bacteriología, PCR, histología e inmunohistoquímica. Los resultados muestran que la vacunación con las cepas Rev 1 ΔeryCD y Rev 1 de B. melitensis no causa daño al sistema reproductivo de los machos cabríos. La cepa B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD mostró menos capacidad para colonizar el tracto reproductivo que la cepa Rev 1 debido a su acción catabólica limitada hacia el eritritol.

Goats were one of the first domesticated animals, around 10500 years ago in the Fertile Crescent. According to the FAO, the world goat population has been estimated to be around 921 million animals, with an increase of more than 20% in the last decade. Goats are a source of milk, meat, and fiber and are adapted to a wide range of grazing environments31. Approximately 90% of goats are found in the developing world, where they are considered one of the most important sources of protein for humans23.

Brucella melitensis is the main causative agent of caprine brucellosis, which leads to significant production losses due to kid mortality and low milk production, and is also the main bacterial zoonosis in Mexico with a significant economic impact on public health20.

Caprine brucellosis has been controlled in most industrialized countries; however, this disease remains endemic in resource-limited settings, where small ruminants are the major livestock species and the main economic livelihood, such as the Mediterranean region, the Middle East, Central Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Latin America23.

The Official Mexican Standard for the control of brucellosis specifies that goats should not be immunized with the B. melitensis Rev 1 vaccine17, as erythritol is known to promote the growth of B. melitensis Rev 1 and this strain has tropism for the male reproductive organs due to its content of erythritol7,15. However, there is no scientific evidence to support that the Rev 1 vaccine causes lesions when applied to kids. From an epidemiological point of view, the use of vaccination against brucellosis in male goats would not be indicated in cases where the herd has low incidence or is free of the disease. Brucellosis in male goats occasionally causes epididymo-orchitis24. Nevertheless, vaccination of kids could be an option in endemic areas of the disease to protect male goats from contracting brucellosis through frequent routes of infection such as licking the genitals of females, or consuming water or food contaminated with the bacteria. In these cases, vaccination would protect against the eventual sacrifice of the kid due to the disease. So our working hypothesis was that the Rev 1 vaccine does not cause lesions on the male genitalia.

The B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD strain was constructed with the same characteristics as strain B. abortus S19. It presents a 702 bp deletion in specific sections of the eryC and eryD genes, inhibiting the ability of microorganisms to catabolize erythritol. Since the wild parental strain Rev 1 contains the complete ery operon, it is capable of metabolizing erythritol, which should contribute to the capacity of the strain to colonize the sexual organs. Hence, vaccination with the B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD strain, with the deleted ery operon, should show different effects on the male goat reproductive tract compared to those of vaccination with the wild parental Rev 1 strain. Therefore the present study aimed to compare the effects caused by vaccination with B. melitensis strains Rev 1 ΔeryCD and Rev 1 on the reproductive tract of young male goats.

Materials and methodsVaccinationForty-eight four-month-old male goats of the Saanen breed were included in the study and were selected from brucellosis-free animals and tested negative in the serological study with the card test. To prevent the possible interference of the vaccine strains in the experiment, the three groups were separated after vaccination. The negative control group and the group vaccinated with Rev 1 were housed in separate pens with no possibility of contact in the facilities of the National Institute of Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIFAP) in Mexico City. Concurrently, the kids of the group vaccinated with the Rev 1 ΔeryCD strain were housed in a ranch of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Zootechnics of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, located in Chalco, State of Mexico. At the beginning of the experiment, three unvaccinated kids were sacrificed to confirm through a serological and bacteriological study that they were negative for brucellosis. Three groups were formed, each one consisting of 15 male goats. The two treatment groups were vaccinated when goats were six months old. The vaccine was applied at this age because vaccination is indicated between three and six months of age, and this allowed us to follow the kids up to eleven months of age when they had already entered puberty. The first group was inoculated with the experimental strain: B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD. A fragment of 1158 bp was extracted from Brucella abortus S19, containing the ΔeryCD deletion, and was obtained by PCR using the oligonucleotides EryCD.R (5′-AGGGCCTTTGCTGTCCGTTC-3′) and EryCD.F (5′-CAATCCGCTGGTCAACCGCT-3′) with B. abortus S19 DNA. Then, the fragment was cloned into pGEM® T-Easy (Promega), completely sequenced to check for the absence of unwanted mutations introduced during the PCR step, and, subsequently, recloned as a NotI fragment into the mobilizable suicide plasmid pJQ200ucl122, to produce pJQ-ΔeryCD. pJQ-ΔeryCD was introduced into the Escherichia coli S17-1 (λ-pir) mobilizing strain27, and used to construct a deletion mutant in B. melitensis Rev 1, following the protocol previously described26.

The second group was inoculated with B. melitensis Rev 1. The Rev 1 vaccine was produced by PRONABIVE Mexico laboratories. The third group (controls) received a vaccination with sterile physiological saline solution. In the three groups, the application was subcutaneous2. The dosage for both strains was 1×109 colony forming units (CFU)/ml, the CFU count was performed following the Miles and Misra method2.

Serological studySerum was obtained from blood samples taken from the jugular vein on day zero, i.e. before the vaccination or euthanasia. Sera were kept in sterilized 1.5ml tubes and frozen at −20°C before utilization. The serum was used for a 3% card test diagnosis of Brucella antibodies9.

Bacteriological studyEuthanasia was conducted under the guidelines of NOM-033-SAG/ZOO16. The animals were sacrificed using a concealed plunger gun and subsequent slitting, as approved by the Institutional Subcommittee for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals Number MC-2018/1-8.

Inguinal lymph nodes, mesenteric nodes, mediastinum, spleen, testicles, epididymis, seminal vesicles, bulbourethral glands, and an ampoule were collected for bacteriological, histology, immunohistochemistry, and PCR studies. Subsequently, three animals of each experimental group were euthanized monthly for the next five months.

The samples of nodes, mesenteric, mediastinum, spleen, testicles, epididymis, seminal vesicles, bulbourethral glands, and the ampoule, were independently macerated in a sterile 2ml saline solution.

The primary isolation of Brucella spp. was performed by inoculating the samples onto Farrell agar plates and incubating them for 10 days at 37°C with 10% CO2. The bacterial cultures were discarded after 10 days of incubation if no growth was visible2. The typical colonies of Brucella spp. were stored at −80°C for further studies.

Eight 10-fold dilutions were made from this solution, each of which was inoculated onto Farrell plates to count CFU/ml. Next, they were incubated for 10 days at 37°C in an aerobic environment2.

Histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and PCRFor the histopathological analysis, the sample tissues were stained with eosin/hematoxylin (EH). Immunohistochemistry was used to analyze the testicles and epididymis obtained during this study3.

DNA was extracted from testicle and epididymis samples using the commercial QIAamp DNA Mini Kit following the manufacturer's instructions. PCR conditions were as described by Sangari and Agüero25.

Statistical analysesDifferences in seroconverted animals between groups in each evaluation were compared using the Chi-square test, SPSS version 25.

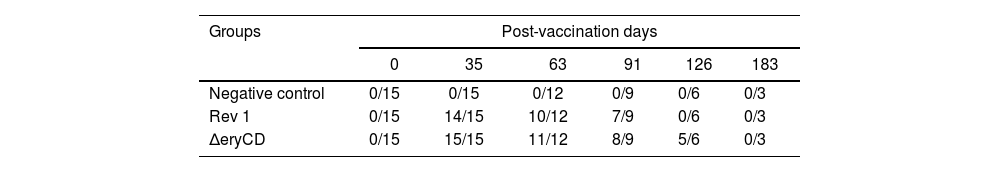

ResultsAll animals in this study were seronegative before vaccination (day 0). In the first month of analysis, 14/15 animals from the B. melitensis Rev 1 group and 15/15 from the B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD group exhibited vaccine antibodies. When tracking humoral immunity, it was found that the negative control group remained negative throughout the study. At each evaluation, the animals in the B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD group showed the highest seropositivity. Moreover, 2/3 animals in this group maintained antibody levels for the longest period, up to 4 months after vaccination. On the other hand, only 1/3 animal in the B. melitensis Rev 1 group showed a persistent serological response for up to 3 months after vaccination (Table 1). However, no evidence of difference between vaccinated groups was found (p≥0.05).

Throughout the study, B. melitensis was never isolated from the organs of the negative control group or the B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD group. The only exception occurred three months after vaccination, when B. melitensis was successfully isolated from left testicle samples of the B. melitensis Rev 1 group. PCR studies showed negative results for all tested organs. B. melitensis DNA was not detected even in the sample that proved positive in bacteriology.

Histopathological examination of testicles and accessory glands proved that the vaccination did not generate any changes in the reproductive system. The analyzed samples exhibited no pathological changes, not even in the animal from which B. melitensis was isolated. Immunohistochemistry results were compatible with the histopathological study, since no B. melitensis antigens were found in the analyzed testicles and epididymides, including in the sample testing positive in the bacteriological study.

DiscussionTo this day, vaccines are still the most successful treatment to prevent infectious diseases in animals and humans19. B. melitensis Rev 1 vaccination has been used effectively around the world to control brucellosis in female goats and domesticated sheep4. The protection conferred by the Rev 1 B. melitensis vaccine at a reduced dose was evaluated in goats immunized five years earlier. Sixteen goats vaccinated five years earlier with Rev 1 with 1×105CFU and 5 unvaccinated goats were challenged with B. melitensis 16M with 4×105CFU by the conjunctival route. After calving or aborting, the goats were sacrificed, and tissue samples were taken for the bacteriological study. The challenge strain was recovered in 12% of the animals in the vaccinated group and 80% in the control group8.

Moreover, there is a conception that males are not relevant for the epidemiology of brucellosis. It has been suggested that vaccination could cause arthritis in up to 13% of vaccinated animals, which would affect their ability to reproduce32. Few studies have been conducted on this subject. Rev 1 vaccine has not been evaluated in young male goats and applied at a complete dose5,10,12,13.

There are two previous cases of vaccination in males. Aldomy et al.1 vaccinated adult males with a reduced dose of Rev 1, monitoring the post-vaccination serological response for up to 24 weeks, where the card test gave positive results throughout the study1. Although they did not carry out a bacteriological study, their results showed longer persistence than those shown in our study, where the positive response to Rev 1 at a complete dose lasted for thirteen weeks.

In another study five adult domestic alpine goats and five mountain goats (Capra ibex) received complete dose conjunctival vaccination of Rev 1 vaccine, collecting sera and urethral swabs for serological and bacteriological monitoring. No clinical signs or specific Brucellosis lesions were observed, and, in the bacteriological study two male ibex presented urogenital excretion at 20 or 45 days post-vaccination. At sacrifice, isolates with a higher bacterial load were obtained at 45 days from ibex compared to domestic goats, while the levels remained between moderate and low when the animals were sacrificed 90 days post-vaccination21. This large number of isolates of the Rev 1 vaccine strain can be attributed to the use in this experiment of a complete Rev 1 dose, which is not recommended for adult animals. For this same reason a comparison with our study cannot be made, as we vaccinated kids with the complete dose of Rev 1 only recommended for young animals.

In the present study, male goats were vaccinated with a complete dose for the first time with the experimental strain B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD and the strain B. melitensis Rev 1. The results in the serological follow-up using the card test were very similar in both vaccinated groups during the 3–4 months after vaccination. These data differ from other studies in which B. melitensis Rev 1 vaccination has been reported to generate a year-long humoral immunity in goats and sheep10,11. This immune response is considered a problem because it interferes with the serological diagnosis after vaccination12.

Nevertheless, protection against Brucella spp. requires a Th1 type immunological response18. Therefore, the cellular response should be studied, regardless of the short duration of the serological response. Moreover, the protection conferred by the studied strains should be further studied.

With regard to bacterial colonization, it is believed that B. melitensis Rev 1 shows tropism for the reproductive organs; however, the present study showed that none of the strains exhibited this characteristic. Only one of the 15 animals vaccinated with B. melitensis Rev 1 exhibited colonization of a testicle. In contrast, the strain could not be isolated from any of the animals vaccinated with B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD. Tolari and Salvi30 isolated Brucella spp. from a goat that was ill with bilateral orchitis and had been immunized against B. melitensis Rev 1. These are the only studies in which positive isolation has been reported. Most studies have found that Brucella does not colonize the reproductive tract5,11–13. In line with these studies, the present research has demonstrated relatively low tropism and colonization of the reproductive organs by both strains. In the case of B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryC, no tropism or colonization were identified. Therefore, this strain could represent a viable option to protect male goats against the illness and avoid the risk of infection.

In this study, the PCR was unable to detect B. melitensis DNA in a bacteriologically positive sample. The PCR only gave positive results when it was directly applied to the isolate. Nevertheless, this is not the first case in which bacteriology is more sensitive than PCR. A study by Buyukcangaz et al.6 on ruminant fetus organs, found that the sensitivity of PCR to detect Brucella spp. was 83% compared to bacteriology. Several reasons have been proposed to explain the low sensitivity of PCR in this context. These are, first, the presence of enzyme inhibitors in organ macerations6; second, the low number of bacteria in the samples6; and finally, the variations in specificity and sensitivity of the PCR method based on the laboratory characteristics29, among other possible reasons. Although the present study expected higher sensitivity from the PCR, the results are similar to those in the previously mentioned studies. This could be related to some factors specified earlier, such as tissue contamination or the fact that it is a biological sample, without discarding the possibility of low quantities of bacteria in the sample.

Histopathological results showed that neither of the strains caused any detectable damage to the reproductive system. These results agree with the observations made by Blasco5, in which animals vaccinated with B. melitensis Rev 1 showed no lesions whatsoever. In those cases that did present some type of damage, it was not possible to isolate the strain; the challenging strain was isolated instead. In the present study, the B. melitensis Rev 1 strain was not isolated from most animals, which directly influenced the absence of injuries. In the case of the positive male goat, it is possible that the infection was just starting to settle, therefore there were no evident alterations. The detection of B. melitensis in testicle and epididymis samples by immunohistochemical analysis was negative in all cases, even in the bacteriologically positive testicle sample. These negative results could be attributed to the fact that tissues colonized by bacteria were not included in the sample28, or because the number of bacteria in the tissue was low14.

The present study shows that vaccination with B. melitensis strains Rev 1 ΔeryCD and Rev 1 causes no damage to the reproductive system of male goats. Strain B. melitensis Rev 1 ΔeryCD displayed reduced capacity to colonize the reproductive tract compared to strain Rev 1, due to its limited catabolic action toward erythritol. Results indicate that these strains do not represent a risk of infection to male goats when used for immunization against brucellosis, an important advantage when considering vaccination in controlled zones or with a high prevalence of the disease.

Further studies are needed regarding antibody permanence to prevent diagnostic misconceptions, and concerning long-term seminal quality in immunized animals to determine if fertility is affected.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was partially supported by project: “Evaluation of encapsulated proteic immunogens to prevent caprine brucellosis” Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT) IT201517.

I.A. López Vásquez received a scholarship from CONACYT.