The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii is a biotherapeutic agent used for the prevention and treatment of several gastrointestinal diseases. We report a case of fungemia in a patient suffering from Clostridiumdifficile-associated diarrhea and treated with metronidazole and a probiotic containing S. cerevisiae var. boulardii. The yeasts isolated from the blood culture and capsules were identified by MALDI-TOF MS and API ID 32 C as S. cerevisiae, and showed the same appearance and color on CHROMAgar Candida. Treatment with fluconazole 400mg/day was initiated and the probiotic was stopped. The patient was discharged from hospital in good condition and was referred to a rehabilitation center. We suggest that the potential benefit of S. cerevisiae var. boulardii should be accurately evaluated, especially in elderly patients. Moreover, all physicians should be trained in the use of probiotic agents and enquire whether the use probiotics was included in the patients’medical histories.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii es un agente bioterapéutico usado en la prevención y el tratamiento de varias enfermedades gastrointestinales. Informamos de un caso de fungemia en una paciente con diarrea asociada a Clostridiumdifficile, y tratada con metronidazol y un probiótico que contenía S. cerevisiae var. boulardii. Las levaduras aisladas a partir del hemocultivo y del contenido de las cápsulas tomadas por la paciente se identificaron como S. cerevisiae mediante MALDI-TOF MS y API® ID 32C, las colonias mostraron el mismo color y aspecto en el medio CHROMAgar™ Candida. Se instauró un tratamiento con fluconazol 400mg/día y se suspendió el probiótico. La paciente fue dada de alta del hospital en buenas condiciones, y remitida a un centro de rehabilitación. Sugerimos que el beneficio potencial del uso de S. cerevisiae var. boulardii debe ser evaluado en cada paciente, especialmente en personas añosas. El uso de probióticos debería incluirse en los interrogatorios orientados al diagnóstico y formar parte de la historia clínica.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is considered part of the normal human intestinal flora. Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii has been used as a probiotic since the 1950s. The yeast S. cerevisiae var. boulardii is a biotherapeutic agent used for the prevention and treatment of several gastrointestinal diseases. This probiotic is used worldwide and has been tested for clinical efficacy against several diseases such as antibiotic-associated diarrhea, acute diarrhea in adults, HIV-related diarrhea, Helicobacter pylori-related diseases, Clostridium difficile and Salmonella typhi infections, and Crohn's disease, among others2,8. Cases of the use of probiotics immediately preceding or concomitant to the occurrence of fungemia by S. cerevisiae are reported in the literature1,6,14, and can lead to septic shock and an increase in mortality rates, especially in immunocompromised patients1.

We report a case of S. cerevisiae fungemia in an elderly patient suffering from C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD), who was treated orally with S. cerevisiae var. boulardii and metronidazole. The identification of S. cerevisiae was confirmed by a proteomic method. The present study questions the safety of this preventive biotherapy.

In March 2017, an 82-year-old woman presented with C.difficile-associated diarrhea and was treated with metronidazole 500mg every 8h for 14 days and with 200mg/day probiotic capsules (Floratil®-Temis Lostalo) for six months. She suffered from Alzheimer's disease, arterial hypertension and diabetes as comorbidities.

In September, she was admitted to the Dr. Julio Mendez Hospital, in the city of Buenos Aires, for a gastrostomy feeding tube placement procedure. The patient developed a fever 48h upon admission. Laboratory tests revealed the following: white blood cell count (WBC) 13800cells/ml and 86.2% neutrophils, platelet count 309000cells/ml, hemoglobin 11g/dl, glycemia 134mg/dl, creatinine 0.44mg/dl, alkaline phosphatase 119U/1, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 44U/1 and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 22U/1.

After obtaining blood (from the peripheral vein) and urine for culture, empirical treatment with vancomycin (1g every 12h) and piperacillin tazobactam (4.5g every 6h) was started. Persistent fever was observed despite the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Yeasts were isolated by the BacT/Alert (BioMériux, France) system from two sets of blood culture. The urine culture was negative. The yeast was cultured in a differential chromogenic medium (CHROMagar Candida, France). Antibiotics were discontinued and treatment with fluconazole 400mg/day was initiated.

Carbohydrate assimilation tests using a commercially available API ID 32C kit (BioMérieux, France) matched the S. cerevisiae profile.

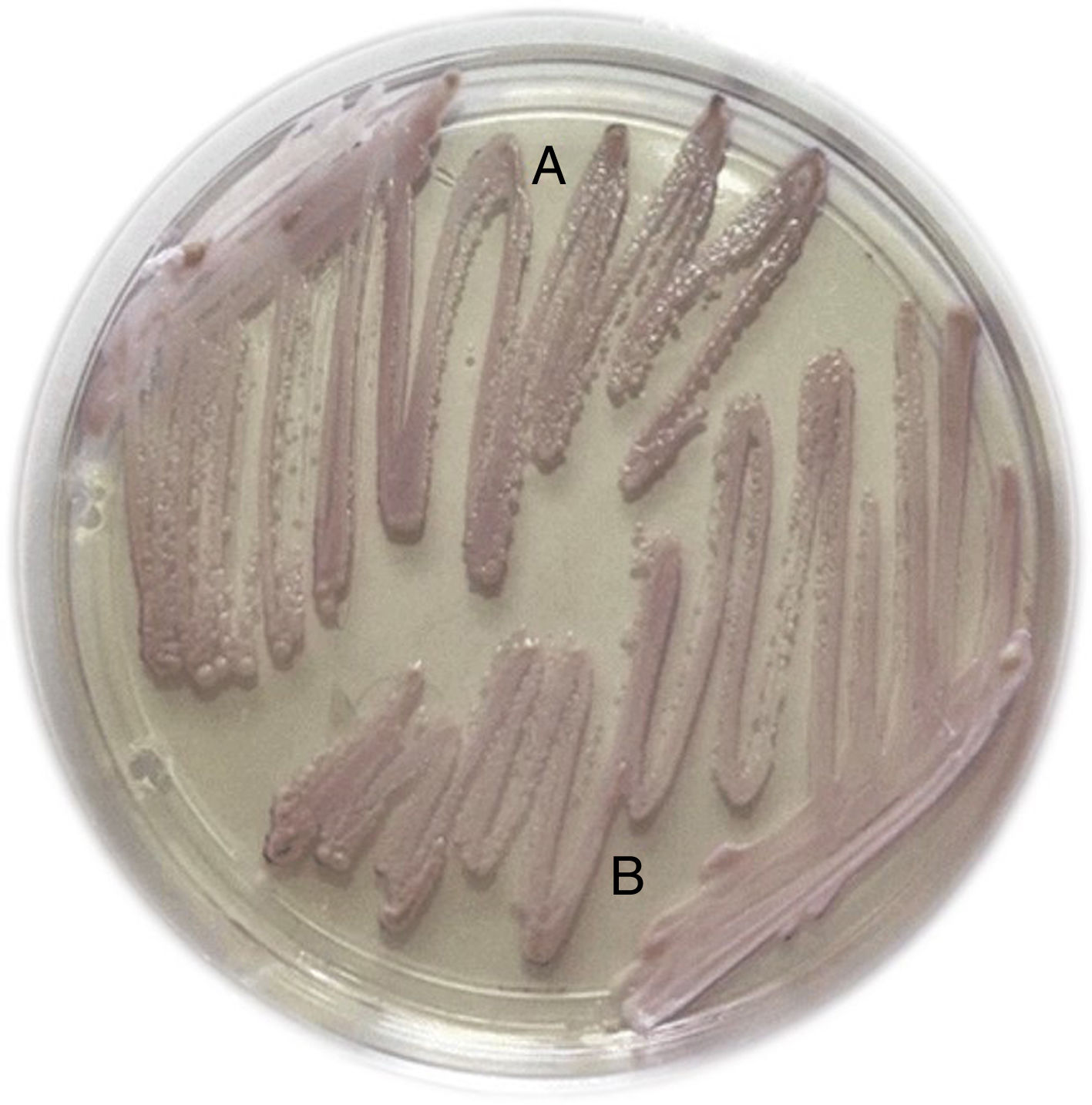

Capsules of the probiotic and the yeast isolated from the blood culture were sent to the medical mycology laboratory. Strains of S. cerevisiae isolated from the blood culture and capsule contents were cultivated in CHROMAgar Candida (CHROMagar Company, Paris, France). They showed the same appearance and color (Fig. 1).

Strains were identified with Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS, Bruker® Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) and the API ID 32C kit (BioMérieux, France). MALDI-TOF analysis was performed with an initial protein extraction step using sterile water, ethanol, formic acid and acetonitrile.

The corresponding mass spectra of both isolates were analyzed, and S. cerevisiae was identified (The score achieved was >2). Scores of 2.0 are accepted for species assignment, and scores 1.7–2.0 are accepted for identification at the genus level. Scores below 1.7 are regarded as unreliable. The use of carbohydrate assimilation tests with API ID 32C matched the S. cerevisiae profile with 99.7 ID (Identification Percentage) and 0.81T (T index). Both isolates showed the same profile and were able to assimilate glucose, galactose, maltose, sucrose and raffinose. The sporulation study on ascospore agar10 was negative in both strains isolated7.

Fluconazole was administered for 18 days and the probiotic treatment was stopped. Follow-up blood cultures were negative. The ultrasound study and computed tomography scan of the abdomen did not show any pathologic alterations. The patient was afebrile with normal WBC counts; therefore, she was discharged from hospital and referred to a rehabilitation center.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Bioethics Committee at Julio Mendez Hospital, in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference for Harmonization. The local ethics committee agreed that the findings in this report were based on normal clinical practice and were therefore suitable for dissemination. A written informed consent was obtained from the patient enrolled in the present study.

S. cerevisiae var. boulardii is usually administered to prevent and treat antibiotic-associated diarrhea and CDAD infection and to improve inflammatory bowel diseases through immunomodulation2,8.

There is, however, a risk of fungemia due to the administration of S. cerevisiae var. boulardii, particularly in critically ill patients2,11,15 mainly immunocompromised individuals and those requiring a central venous catheter14. Since the 1990s, invasive fungal infections have been reported in patients treated with S. cerevisiae var. boulardii as a probiotic6 as well as in patients in close physical proximity to those being treated1. In the patient herein studied, the identified risk factors for fungemia were treatment with a probiotic containing S. cerevisiae var. boulardii, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, diabetes and age-associated immune dysfunction. The fungemia was probably due to damage induced by the gastrostomy feeding tube placement and digestive translocation by the oral administration of S. cerevisiae var. boulardii. Portals of entry for this yeast include translocation of ingested microorganisms from the enteral or oral mucosa and contamination of intravenous catheter insertion sites1,8.

In this patient, the fungemia was detected 180 days after the administration of the probiotic. In a review of the literature including 60 cases of S. cerevisiae fungemia, a median of 10±62.3 days (range, 4–300 days) was observed after the administration of the biotherapeutic agent14. The patient recovered when she stopped ingesting health food containing yeasts and was treated with fluconazole. The antifungal agent of choice for treatment of Saccharomyces species has not been finally established; however, amphotericin B and fluconazole seems to be preferable14.

Likewise, several cases described in the literature, even those of immunocompromised patients, were reported to attain a rapid response once the treatment with the probiotic preparation and/or the antifungal therapy was terminated and the central venous catheter was removed1. Altogether, these observations underscore the prognostic importance of the rapid diagnosis of fungemia.

The isolates obtained from the patient and the probiotic (Floratil®) were identified as S. cerevisiae by the MALDI-TOF analysis. Characterization of Saccharomyces boulardii as a separate species was supported by the lack of galactose and sporulation as compared to S.cerevisiae12. However, a narrowed biochemical profile of S. boulardii with galactose, maltose and a raffinose-positive phenotype was reported by McCullough et al.13 Despite some differences found in phenotyping, genotyping and proteomic studies7, S. cerevisiae var. boulardii was definitively regarded as a member of the species S.cerevisiae9. Molecular phylogenetic and typing techniques suggested that S. cerevisiae var. boulardii forms a separate cluster but belongs to the species S.cerevisiae14. These findings have also been supported by other clinical studies, in which S. cerevisiae recovered from patients and S. cerevisiae var. boulardii strains isolated from probiotic preparations were proved to be genomically identical1,11,14.

It is important to highlight that this report presents limitations due to the unavailability of molecular DNA-based analyses to confirm that the yeast isolated from the blood culture was the same as that found in the probiotic. However, other clinical studies conducted in similar situations showed that the S. cerevisiae found in the culture obtained from the patient and the S. cerevisiae var. boulardii in the probiotic administered were genetically identical11,14.

Physicians are often undereducated about probiotic agents and do not ask their patients whether they have received probiotics as part of their treatment, thus they may be unaware of their patients’ utilization of these agents. Both guidelines on the therapy of CDAD provided by the Infectious Diseases Society of America's (IDSA)3 and by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID)4 do not yet recommend the use of probiotics as an adjunctive measure to prevent or treat CDAD.

In the cases of fungemia caused by S. cerevisiae, it is necessary to determine whether the patient is being treated with one of these biotherapeutic agents. It is important to emphasize the role of this probiotic, because it was responsible for 40.2% of invasive Saccharomyces infections reported in the literature6. Physicians and hospital systems need to be vigilant for potential rare cases of adverse events6.

Furthermore, the largest randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study to date that has been recently published found no benefits in the administration of the S. cerevisiae var. boulardii probiotic to prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhea in a population of hospitalized patients who received systemic antibiotic treatment5.

S. cerevisiae var. boulardii fungemia may be underestimated as an iatrogenic infection. Even if the clinical impact of the infection is moderate, the potential benefit of S. cerevisiae var boulardii should be well evaluated accordingly, especially in elderly patients with underlying diseases that have predisposing factors for fungemia.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This research was supported by the School of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires, Grant Number UBACyT 20020150100158BA.