The genus Geobacillus is composed of thermophilic bacteria that exhibit diverse biotechnological potentialities. Specifically, Geobacillus stearothermophilus is included as a test bacterium in commercial microbiological inhibition methods, although it exhibits limited sensitivity to aminoglycosides, macrolides, and quinolones. Therefore, this article evaluates the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of five test bacteria (G. stearothermophilus subsp. calidolactis C953, Geobacillus thermocatenulatus LMG 19007, Geobacillus thermoleovorans LMG 9823, Geobacillus kaustophilus DSM 7263 and Geobacillus vulcani 13174). For that purpose, the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 21 antibiotics were determined in milk samples for five test bacteria using the radial diffusion microbiological inhibition method. Subsequently, the similarities between bacteria and antibiotics were analyzed using cluster analysis. The dendrogram of this multivariate analysis shows an association between a group formed by G. thermocatenulatus and G. stearothermophilus and another by G. thermoleovorans, G. kaustophilus and G. vulcani. Finally, future microbiological methods could be developed in microtiter plates using G. thermocatenulatus as test bacterium, as it exhibits similar sensitivities to G. stearothermophilus. Conversely, G. vulcani, G. thermoleovorans and G. kaustophilus show higher MICs than G. thermocatenulatus.

El género Geobacillus está compuesto por bacterias termófilas que poseen diversas potencialidades biotecnológicas. Puntualmente, G. stearothermophilus se incluye como bacteria utilizadas para testeo en pruebas comerciales de inhibición microbiana para detectar residuos de antibióticos en alimentos, aunque presenta una limitada sensibilidad frente a aminoglucósidos, macrólidos y quinolonas. En este trabajo se evaluaron los perfiles de sensibilidad antibiótica de cinco bacterias utilizadas para testeo: G. stearothermophilus subsp. calidolactis C953, G. thermocatenulatus LMG 19007, G. thermoleovorans LMG 9823, G. kaustophilus DSM 7263 y G. vulcani 13174. Para ello, se determinaron las concentraciones inhibitorias mínimas (CIM) de 21 antibióticos en muestras de leche frente a las bacterias mencionadas mediante el método de inhibición microbiológica de difusión radial. Posteriormente, se analizaron las similitudes entre estas bacterias y entre los diferentes antibióticos evaluados mediante el análisis de clusters. El dendrograma de este análisis multivariante detectó un grupo formado por G. thermocatenulatus y G. stearothermophilus y otro constituido por G. thermoleovorans, G. kaustophilus y G. vulcani. En el futuro se podrían desarrollar métodos microbiológicos en placas de microtitulación utilizando G. thermocatenulatus como bacteria-test, puesto que este microorganismo posee sensibilidades similares a G. stearothermophilus. Por el contrario, G. vulcani, G. thermoleovorans y G. kaustophilus presentan CIM superiores a G. thermocatenulatus.

The genus Geobacillus is characterized by including Gram positive, aerobic or facultative anaerobic rod-shaped bacteria, with the ability to form endospores32 and grow at a wide range of temperatures (35–80°C). This group includes Geobacillus stearothermophilus, Geobacillus thermocatenulatus, Geobacillus thermoleovorans, Geobacillus kaustophilus, and Geobacillus vulcani, among others.

Thermophilic bacteria of this genus are found in a variety of harsh environments such as high-temperature oil fields, marine vents, corroded pipes in extremely deep wells, African and Russian hot springs and the Marianas Trench, but can also be found in manure hay, garden soils, and the Sahara Desert4,31. This unexpected or inconsistent distribution of Geobacillus spp. has been discussed by Zeigler32, who correlated this inconsistency with its worldwide spread.

These bacteria are used in various industrial applications19, such as enzyme production3,7,10,11,16,25, bioethanoll6,17, papermaking27,28, bioremediation15,18,23,30, and animal feed production9.

In addition, G. stearothermophilus is specifically used as a test bacterium in commercial microbiological methods, such as Delvotest®, Eclipse® and Charm BY®, for the detection of antibiotic residues in food14. The advantages of G. stearothermophilus over other test bacteria include its low response times (2.5h), high incubation temperature (selective growth of this test bacterium), low cost and easiness to use in laboratories, high sensitivity to a wide group of antibiotics (beta-lactams, tetracyclines and sulfonamides), dichotomous responses (positive vs. negative) and possibility to be stored at 4°C for long periods of time14. However, the use of other strains of the genus Geobacillus (G. vulcani, G. thermocatenulatus, G. thermoleovorans and G. kaustophilus) for the development of methods to detect antibiotic residues in fluid matrices such as milk and meat extract has not yet been reported.

Before developing new bioassays, the susceptibility profiles of thermophilic bacteria to different antibiotics should be investigated. This can be achieved by using different antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods such as the agar dilution method, the broth macrodilution method, the disc diffusion/Kirby–Bauer method, Etest, the agar diffusion method in Petri dishes, and the microdilution method, which allow to estimate the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each antibiotic2,24.

Based on the above, the aim of this study was to analyze the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of thermophilic bacteria of the genus Geobacillus and identify similarities among the different test bacteria, with the purpose of recommending strains that can be used in future microbiological techniques for the detection of antibiotic residues in fluid matrices.

Materials and methodsMicroorganismsThe following commercially acquired strains were used for this study: G. stearothermophilus subsp. calidolactis C953 (Merck®, Ref. 1.11499, KGAA, Darmstadt, Germany), G. thermocatenulatus LMG 19007 (Leibniz Institute DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany), G. thermoleovorans LMG 9823 (Leibniz Institute DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany), G. kaustophilus DSM 7263 (Leibniz Institute DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) and G. vulcani 13174 (Leibniz Institute DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany).

Milk samplesFor the preparation of antibiotic solutions, milk samples were used from individual cows (Las Colonias, Santa Fe, Argentina) that were in the middle of the lactation period, untreated and not medicated before or during sampling. In addition, milk samples with low somatic cell count (SCC<300,000cells/ml) and low total bacterial count (TBC<400,000cells/ml) were selected to avoid potential interference in the inhibition of microbiological methods.

Antibiotic-fortified milk solutionsTwenty-one antibiotics (10 beta-lactams, 4 macrolides, 3 quinolones, 3 tetracyclines, and neomycin) were used. The solutions of each antibiotic were prepared by successive dilutions of a stock solution (1000mg/l) using antibiotic-free milk samples that tested negative to the Delvotest® “SP” method, which is considered the reference method2,8. For the preparation of the successive dilutions, volumes of stock solutions of each antibiotic containing less than 1% of the solution in milk were used13 in order not to alter the composition of the milk samples. In the study of antibiotic susceptibility for each test bacterium, five concentrations were prepared in ascending order of concentration (C1, C2, C3, C4 and C5), with each concentration being two-fold higher than the previous one (Table 1), using negative control milk samples.

Antibiotic concentrations (μg/l) used for each test bacterium in the microbiological inhibition method.

| Antibiotics | G. stearothermophilus | G. thermoleovorans | G. vulcani | G. kaustophilus | G. thermocatenulatus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-lactams | |||||

| Amoxycillin | 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 | 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 | 12, 24, 48, 96, 192 | 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 | 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 |

| Ampicillin | 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 | 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 | 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 | 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 | 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 |

| Cloxacillin | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 400, 800, 1600, 3200, 6400 | 15, 30, 60, 120, 240 |

| Oxacillin | 15, 30, 60, 120, 240 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 50, 100, 200, 400, 800 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 15, 30, 60, 120, 240 |

| Penicillin “G” | 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 | 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 | 12, 24, 48, 96, 192 | 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 | 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 |

| Cephalexin | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 |

| Cefadroxil | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 1000, 2000, 400, 800, 16000 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 |

| Cefoperazone | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 |

| Ceftiofur | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 |

| Cefuroxime | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 |

| Tetracyclines | |||||

| Chlortetracycline | 300, 600, 1200, 2400, 4800 | 800, 1600, 3200, 6400, 12800 | 400, 800, 1600, 3200, 6400 | 1000, 2000, 400, 800, 16000 | 400, 800, 1600, 3200, 6400 |

| Oxytetracycline | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 1000, 2000, 400, 800, 16000 | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 |

| Tetracycline | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 400, 800, 1600, 3200, 6400 | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 1000, 2000, 400, 800, 16000 | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 |

| Quinolones | |||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 5000, 10000, 20000, 40000, 80000 | 2000, 400, 800, 16000, 32000 | 3000, 6000, 12000, 24000, 48000 | 5000, 10000, 20000, 40000, 80000 | 2000, 400, 800, 16000, 32000 |

| Enrofloxacin | 5000, 10000, 20000, 40000, 80000 | 2000, 400, 800, 16000, 32000 | 3000, 6000, 12000, 24000, 48000 | 5000, 10000, 20000, 40000, 80000 | 2000, 400, 800, 16000, 32000 |

| Marbofloxacin | 5000, 10000, 20000, 40000, 80000 | 2000, 400, 800, 16000, 32000 | 3000, 6000, 12000, 24000, 48000 | 5000, 10000, 20000, 40000, 80000 | 2000, 400, 800, 16000, 32000 |

| Macrolides and neomycin | |||||

| Erythromycin | 300, 600, 1200, 2400, 4800 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 1000, 2000, 400, 800, 16000 | 300, 600, 1200, 2400, 4800 | 800, 1600, 3200, 6400, 12800 |

| Lincomycin | 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200 | 150, 300, 600, 1200, 2400 | 1000, 2000, 400, 800, 16000 | 1000, 2000, 400, 800, 16000 | 600, 1200, 2400, 4800, 9600 |

| Neomycin | 1500, 3000, 6000, 9000, 18000 | 750, 1500, 3000, 6000, 12000 | 1500, 3000, 6000, 9000, 18000 | 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 4000 | 8000, 16000, 32000, 64000, 128000 |

| Tilmicosin | 800, 1600, 3200, 6400, 12800 | 50, 100, 200, 400, 800 | 400, 800, 1600, 3200, 6400 | 20, 40, 80, 160, 320 | 400, 800, 1600, 3200, 6400 |

| Tylosin | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 50, 100, 200, 400, 800 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 | 20, 40, 80, 160, 320 | 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 |

Mueller Hinton agar (38g/l, Biokar®, Ref. 10272, France) fortified with glucose (10g/l, Sigma Aldrich®, Ref. G8270, USA) at pH 7±0.1 was used. After sterilizing the culture medium in an autoclave (121°C – 15min), the agar was inoculated with a spore suspension of each test bacterium evaluated to achieve a concentration of 1×105spores/ml in the culture medium. Then, a volume of 14ml of culture medium was added to each Petri dish (90mm in diameter) to obtain a thickness of 2.2mm. For each test bacteria (5) and antibiotic (21), 12 microbiological bioassays were prepared in Petri dishes (5×21×12=1260 bioassays in total). Subsequently, the plates were cooled on a flat level surface to obtain a layer of uniform thickness2.

Next, once the culture medium solidified, seven cylindrical perforations (8mm in diameter) were made in each plate. Six of the perforations were distributed at a 60° angle, while the remaining perforation was made in the center of the plate where the antibiotic-free sample (AFS) was dispensed2.

For each test bacterium, 12 bioassays were prepared using milk samples fortified with the five concentrations (C1, C2, C3, C4 and C5) of the antibiotics detailed in Table 1. As shown in Figure 1, the intermediate concentration (C3) was considered a control sample and was analyzed alternately in triplicate in each of the 12 plates (36 replicates in total). This concentration (C3) was used for the correction of the inhibitory halos due to possible variations in the preparation of the bioassays2. Each of the four remaining concentrations (C1, C2, C4 and C5) was plated in triplicate on three plates (9 replicates). In each well of the Petri dishes, a volume of 70μl of antimicrobial-fortified milk sample (Table 1) was dispensed.

Distribution of the different concentrations of antibiotics in milk samples used in the microbiological inhibition method in Petri dishes. C1: concentration 1; C2: concentration 2; C3: concentration 3 (control sample); C4: concentration 4; C5: concentration 5; AFS: antibiotic-free sample.

Subsequently, the plates were incubated at 64°C for 6h until the formation of clear, different and measurable inhibitory halos at the five concentrations of the antibiotics tested. Lastly, the diameters of the inhibitory halos (including the 8-mm well) were measured in duplicate, using a Vernier caliper with a sensitivity of ±0.1mm. Minimal increases of 2mm in the diameter of the inhibition halos (8mm+2mm=10mm) were recorded as significant inhibitions.

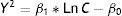

Statistical analysisCalculation of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)The relationship between the inhibition halos and the concentrations of each antibiotic and test bacterium was established by using the regression model proposed by Bonev et al.5:

where Y represents the diameter of the inhibition zone; D is the diffusion coefficient of the antibiotic; t is the incubation time (constant=6h); Ln C is the logarithmic transformation of the antibiotic concentration; and Ln MIC is the logarithmic transformation of the MIC at the end of the halo. This Eq. (1) can be solved using the following linear regression model26:where Y2 represents the response variable and Ln C is the predictor variable. The MIC of each antibiotic and test bacterium was calculated using Eq. (3) and the coefficients β0 and β1 estimated by the linear regression model, as described below:Determination of similarities by using cluster analysisTo visualize associations between test bacteria and antibiotics, we used cluster analysis. Initially, the association of antibiotics was studied by using the hierarchical cluster analysis26 with the Ward algorithm and the Euclidean distance of the MICs. Then, the similarities between the different strains of Geobacillus were analyzed by the hierarchical cluster analysis using the Ward algorithm and the Euclidean distance of the MIC values.

Results and discussionMinimum inhibitory concentrationsTable 2 shows the parameters β0 and β1 and the regression coefficient (R) calculated by means of the linear regression model for the 21 antibiotics and five test bacteria of the genus Geobacillus here evaluated. Regression coefficients were high, with values between 0.906 (chlortetracycline, G. thermocatenulatus) and 0.998 (cloxacillin, G. stearothermophilus), evidencing the linear proportionality between the squares of the inhibitory halos (Y2) and the logarithmic transformations of the antibiotic concentrations (Ln C), according to Bonev et al.5 Next, the MICs were calculated using Eq. (3) for each antibiotic and test bacterium (Table 3).

Parameters estimated by the model for different bacteria of the genus Geobacillus.

| Antibiotics | G. stearothermophilus | G. thermoleovorans | G. vulcani | G. kaustophilus | G. thermocatenulatus | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β0 | β1 | R | β0 | β1 | R | β0 | β1 | R | β0 | β1 | R | β0 | β1 | R | |

| Beta-lactams | |||||||||||||||

| Amoxycillin | −42.2 | 199.3 | 0.968 | −223.6 | 294.8 | 0.931 | −337.7 | 427.8 | 0.996 | −201.9 | 276.9 | 0.945 | −146.1 | 322.1 | 0.935 |

| Ampicillin | −32 | 189.9 | 0.971 | −247.7 | 285.4 | 0.933 | −228.8 | 343.9 | 0.984 | −116.7 | 260.8 | 0.985 | −127.1 | 291.4 | 0.958 |

| Cloxacillin | −645.4 | 409.7 | 0.998 | −1220.8 | 596.0 | 0.995 | −599.1 | 350.9 | 0.987 | −843.4 | 402.4 | 0.966 | −237.5 | 250.4 | 0.912 |

| Oxacillin | −199.5 | 243.2 | 0.977 | −1027.7 | 539.6 | 0.964 | −702.3 | 446.7 | 0.981 | −751.2 | 418.1 | 0.987 | −263.9 | 358.1 | 0.997 |

| Penicillin “G” | −4.5 | 219.2 | 0.924 | −355.9 | 419 | 0.946 | −387.2 | 484.2 | 0.997 | −249.1 | 322.0 | 0.975 | −230.1 | 419.2 | 0.946 |

| Cephalexin | −327 | 195.0 | 0.922 | −794.7 | 437.4 | 0.969 | −781.2 | 445.3 | 0.992 | −909.5 | 425.4 | 0.972 | −760.5 | 414.5 | 0.967 |

| Cefadroxil | −505.1 | 290.9 | 0.972 | −682.3 | 431.8 | 0.975 | −672.8 | 428.1 | 0.998 | −617.8 | 380.3 | 0.990 | −834.6 | 470.7 | 0.975 |

| Cefoperazone | −558.4 | 340.4 | 0.982 | −640.2 | 350.6 | 0.964 | −441.4 | 280.0 | 0.985 | −405.5 | 240.1 | 0.971 | −638.1 | 415.6 | 0.974 |

| Ceftiofur | −528.5 | 310.8 | 0.993 | −779.9 | 402.2 | 0.912 | −572.1 | 663.3 | 0.995 | −1012.4 | 485.0 | 0.997 | −794.9 | 438.6 | 0.997 |

| Cefuroxime | −539.4 | 333.5 | 0.986 | −768.5 | 463.0 | 0.979 | −481.4 | 366.0 | 0.988 | −852.7 | 460.6 | 0.980 | −538.1 | 337.9 | 0.937 |

| Tetracyclines | |||||||||||||||

| Chlortetracycline | −307.6 | 174.3 | 0.994 | −27.9 | 80.3 | 0.959 | −445.1 | 217.2 | 0.963 | −625.2 | 262.0 | 0.988 | −622.5 | 305.1 | 0.906 |

| Oxytetracycline | −140.4 | 115.7 | 0.982 | −572.2 | 324.9 | 0.947 | −614.6 | 293.8 | 0.975 | −438.8 | 217.1 | 0.911 | −455.5 | 245.5 | 0.958 |

| Tetracycline | −182.7 | 134.3 | 0.984 | −620.3 | 271.8 | 0.947 | −720.5 | 326.1 | 0.922 | −481.5 | 245.9 | 0.986 | −589.3 | 297 | 0.953 |

| Quinolones | |||||||||||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | −929.3 | 324.9 | 0.995 | −1126.0 | 385.2 | 0.983 | −963.9 | 337.1 | 0.986 | −1257.6 | 371.5 | 0.992 | −1322.7 | 452.2 | 0.969 |

| Enrofloxacin | −835.4 | 287.7 | 0.991 | −709.9 | 231.9 | 0.912 | −966.7 | 315.2 | 0.991 | −1119.5 | 319.6 | 0.980 | −1060.4 | 354.7 | 0.957 |

| Marbofloxacin | −995.7 | 318.1 | 0.996 | −650.4 | 216.1 | 0.919 | −1131.9 | 363.4 | 0.991 | −1246.7 | 359.7 | 0.990 | −975.7 | 351.0 | 0.982 |

| Macrolides and neomycin | |||||||||||||||

| Erythromycin | −428.3 | 211.0 | 0.994 | −317.2 | 211.6 | 0.989 | −159.4 | 109.7 | 0.986 | −350.2 | 225.4 | 0.973 | −521.5 | 233.9 | 0.977 |

| Neomycin | −369.3 | 161.6 | 0.993 | −215.2 | 153.7 | 0.960 | −223.3 | 111.3 | 0.985 | −300.3 | 177.0 | 0.953 | −527.0 | 170.3 | 0.986 |

| Lincomycin | −243.6 | 207.5 | 0.962 | −376.8 | 234.6 | 0.974 | −644.3 | 262.1 | 0.997 | −326.9 | 195.1 | 0.965 | −610.0 | 270.5 | 0.989 |

| Tilmicosin | −398.6 | 193.1 | 0.997 | −278.4 | 226.7 | 0.988 | −493.5 | 228.4 | 0.974 | −97.6 | 137.6 | 0.975 | −364.1 | 179.8 | 0.987 |

| Tylosin | −262.5 | 183.7 | 0.985 | −366.9 | 267.8 | 0.977 | −314.5 | 213.7 | 0.988 | −87.2 | 174.6 | 0.968 | −271.7 | 177.0 | 0.948 |

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (μg/l) for test bacteria of the genus Geobacillus and maximum residue limits (μg/l) in milk.

| Antibiotics | MRL | G. stearothermophilus | G. thermoleovorans | G. vulcani | G. kaustophilus | G. thermocatenulatus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-lactams | ||||||

| Amoxycillin | 4 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| Ampicillin | 4 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Cloxacillin | 30 | 38 | 114 | 54 | 148 | 12 |

| Oxacillin | 30 | 7 | 90 | 40 | 66 | 6 |

| Penicillin “G” | 4 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 4 |

| Cephalexin | 100 | 65 | 76 | 59 | 151 | 77 |

| Cefadroxil | – | 61 | 43 | 37 | 46 | 39 |

| Cefoperazone | 50 | 47 | 76 | 40 | 55 | 70 |

| Ceftiofur | 100 | 52 | 70 | 37 | 124 | 76 |

| Cefuroxime | – | 44 | 50 | 22 | 78 | 52 |

| Tetracyclines | ||||||

| Chlortetracycline | 100 | 60 | 9 | 149 | 260 | 178 |

| Oxytetracycline | 100 | 19 | 70 | 135 | 112 | 87 |

| Tetracycline | 100 | 26 | 248 | 205 | 101 | 117 |

| Quinolones | ||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 100 | 749 | 903 | 782 | 2667 | 970 |

| Enrofloxacin | 100 | 849 | 1593 | 1217 | 3430 | 1167 |

| Marbofloxacin | 75 | 1378 | 1408 | 1357 | 3034 | 659 |

| Macrolides and neomycin | ||||||

| Erythromycin | 40 | 110 | 33 | 33 | 43 | 194 |

| Lincomycin | 150 | 20 | 46 | 291 | 41 | 190 |

| Neomycin | 1500 | 203 | 36 | 114 | 66 | 1360 |

| Tilmicosin | 50 | 118 | 18 | 164 | 6 | 114 |

| Tylosin | 50 | 29 | 26 | 32 | 4 | 44 |

With respect to penicillins, G. stearothermophilus and G. thermocatenulatus showed great sensitivity toward these molecules, since their MIC values were low. In contrast, G. thermoleovorans, G. kaustophilus and G. vulcani exhibited MICs of penicillins between 1.5 (3μg/l of ampicillin, G. kaustophilus) and 12.8 times higher (90μg/l of oxacillin, G. thermoleovorans) than those obtained by G. stearothermophilus (Table 3).

With respect to cephalosporins, the five test bacteria exhibited similar susceptibilities for the five cephalosporins studied, since their MIC values were between 37μg/l of ceftiofur for G. vulcani and 151μg/l of cephalexin for G. kaustophilus. In addition, the MICs of cephalosporins were higher than those observed for penicillins for all the test bacteria studied.

With regard to tetracyclines, G. stearothermophilus exhibited a high level of susceptibility to all three tetracyclines, in comparison to the other test bacteria, with the exception of G. thermoleovorans (which showed MIC values of 9μg/l for chlortetracycline and 70μg/l for oxytetracycline) and G. thermocatenulatus (which showed a MIC value for 87μg/l of oxytetracycline). On the other hand, G. vulcani exhibited lower susceptibility to tetracyclines than G. stearothermophilus (Table 3).

It should be noted that none of the five test bacteria analyzed showed susceptibility toward the three fluoroquinolones, since they had to be present at concentrations between 659μg/l (marbofloxacin, G. thermocatenulatus) and 3430μg/l (enrofloxacin, G. kaustophilus) to produce noticeable inhibitory halos (Table 3).

Table 3 shows that the five test bacteria exhibited adequate sensitivities for tylosin residues, but lower for tilmicosin, erythromycin–neomycin (with the exception of G. stearothermophilus and G. thermocatenulatus) and lincomycin (with the exception of G. vulcani and G. thermocatenulatus).

In the literature that we reviewed, we found reports only mentioning the detection limits of G. stearothermophilus in Petri dishes. Nouws et al.22, for example, reported similar detection limits in cow milk samples for the five penicillins (amoxycillin, ampicillin, cloxacillin, oxacillin, and penicillin) and for cephalexin, cefoperazone, ceftiofur, cefuroxime and tylosin. Similarly, in a previous study, we obtained detection limits similar to those reported in Table 3 for amoxycillin, ampicillin, penicillin, cephalexin, cefoperazone and tylosin in sheep milk samples, although we did not observe inhibitions when the milk contained quinolone residues1.

Determination of similarities by the hierarchical cluster analysisFigure 2 shows the associations of the 21 antibiotics determined by cluster analysis using the MICs of the evaluated five test bacteria. The figure shows the formation of two large clusters (Cluster “A” and Cluster “B”), which reveal two different types of antimicrobial susceptibilities for these test bacteria.

Cluster “A” (Euclidean distance less than 4) includes antibiotics with lower MICs (beta-lactams, tetracyclines, macrolides and lincomycin), as described above. The first associations occur for the group of penicillins, cephalosporins and tylosin, which have low MICs, followed by tetracyclines and other antimicrobials (macrolides). Finally, neomycin joins Cluster “A” with a greater Euclidean distance.

Cluster “B” (Euclidean distance greater than 4) consists of fluoroquinolones, which have high MICs and finally join Cluster “A” at a high Euclidean distance (greater than 20). Thus, the low susceptibility of thermophilic bacteria to these antimicrobials is highlighted.

This association of antibiotics for the five Geobacillus indicates a high sensitivity of these thermophilic bacteria toward penicillins and cephalosporins followed by a medium sensitivity for tetracyclines and a low sensitivity for quinolones. In addition, sensitivity studies with G. stearothermophilus indicate a similar behavior when these antibiotics are analyzed in cow22 and ewe1 milk.

To establish a cluster of test bacteria based on susceptibility associations, fluoroquinolones were removed from the analysis because they exhibited high MIC values. Figure 3 shows a cluster made up of the MICs of 18 antibiotics (Table 3) that exhibited inhibitory effects toward the bacteria evaluated. This figure shows two groups: Group A (G. stearothermophilus and G. thermocatenulatus), with a Euclidean distance similar to 1.0, and Group B (G. thermoleovorans, G. kaustophilus and G. vulcani), with a Euclidean distance greater than 2.0. These associations can be attributed to the high susceptibilities of G. stearothermophilus and G. thermocatenulatus (Group A) toward penicillins, cephalosporins and other antimicrobials (erythromycin, tilmicosin and tylosin), and the similar susceptibilities of G. thermoleovorans, G. kaustophilus and G. vulcani (Group B) to other antimicrobials (aminoglycosides and macrolides), with the exception of G. vulcani (higher MICs of lincomycin and tilmicosin), which is later integrated into Group B.

Regarding the associations of different strains of the genus Geobacillus, it should be noted that previous studies have reported similar associations when analyzing gene sequences encoding 16S rRNA6,19–21. Nazina et al.21, for example, analyzed the 16S rDNA genes present in 26 strains of Geobacillus and constructed a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method and the bootstrap analysis contained in the Treecon software package29. The results showed the presence of a cluster composed of G. thermoleovorans, G. kaustophilus and G. vulcani, and another cluster composed of G. stearothermophilus and G. thermocatenulatus, in accordance with those determined in this work when the MICs were used as an associative variable. Similarly, Najar and Thakur19 obtained a phylogenetic tree using the associative neighbor-joining method for the 16S rDNA gene sequences corresponding to 19 strains of Geobacillus. The results indicated a cluster composed of G. thermoleovorans, G. lituanicus, G. kaustophilus and G. vulcani, into which a cluster containing G. stearothermophilus and G. thermocatenulatus was subsequently incorporated. This cluster of thermophilic bacteria is similar to the dendrogram in Figure 3, which uses the MIC values as a property of similarity. Brumm et al.6 also performed a phylogenetic analysis of the nucleotide sequences (16S rDNA) present in 24 strains of Geobacillus by applying neighbor-joining and BioNJ algorithms and highlighted a grouping similar to the cluster shown in Figure 3. The formation of a group composed mainly of G. thermoleovorans, G. vulcani and G. kaustophilus, followed by another group composed of G. thermocatenulatus and G. stearothermophilus, would reflect the evolutionary history of these thermophilic bacteria.

Due to the similarities between bacterial susceptibilities and bacterial ribosomal DNA (16S rDNA) of different strains of the genus Geobacillus, the MICs calculated in this work could be analyzed together with the information of the complete genome of these bacteria through the use of appropriate bioinformatic tools12. Thus, associations of susceptibilities with bacterial genes could be revealed.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, it can be established that the cluster analysis dendrogram shows two different groups of thermophilic bacteria. The first one is formed by G. thermocatenulatus and G. stearothermophilus, while the second is made up of G. thermoleovorans, G. kaustophilus and G. vulcani.

Since the minimum inhibitory concentrations of G. thermocatenulatus and G. stearothermophilus are similar and lower than those observed for other Geobacillus, future bioassays in microtiter plates with G. thermocatenulatus spores should be optimized. The development of new bioassays using this test bacterium should improve some of the properties of current commercial methods, such as response time, specificity, detection limits and robustness, among others.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This research was carried out as part of the projects CAI+D́20 (PI50320220100184LI, Universidad Nacional del Litoral) and PICT 2841/2017 (Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica, Argentina).