Toxocariasis is an infection that has worldwide distribution. Toxocara canis is the most relevant agent due to its frequent occurrence in humans. Soil contamination with embryonated eggs is the primary source of T. canis. This study aimed to determine the seroprevalence of toxocariasis in 10-month to 3 year-old abandoned infants, considered to be at high risk because of their orphanhood status and early age. Blood samples were collected from 120 children institutionalized in an orphanage in the city of La Plata. In this study, we observed 38.33% of seropositive cases for T. canis by ELISA and 45% by Western blot techniques; significant differences among groups A (<1 year), B (1–2 years) and C (>2 years) were also found. In research group A, children presented a seropositivity rate of 23.91%, in group B of 42.85% and in group C of 56%, which indicates an increase in frequency as age advances, probably because of greater chances of contact with infective forms of the parasite since canines and soil are frequently infected with T. canis eggs. Abandoned children come from poor households, under highly unsanitary conditions resulting from inadequate or lack of water supply and sewer networks, and frequent promiscuity with canines, which promotes the occurrence of parasitic diseases. These children are highly vulnerable due to their orphanhood status and age.

La toxocariosis es una enfermedad presente en todo el mundo. Como causa primaria de infección se cita la contaminación de los suelos con huevos embrionados de Toxocara canis. Nuestro objetivo fue determinar la seroprevalencia de toxocariosis en niños expósitos (abandonados) de 10 meses hasta 3 años, los que se consideran de alto riesgo por su condición de orfandad y escasa edad. Las muestras de sangre fueron recolectadas de 120 niños institucionalizados en un orfelinato de la ciudad de La Plata. En este estudio, se observó un porcentaje de seropositivos para T. canis de 38,33 % por la técnica de ELISA y de 45 % por la técnica de Western blot, con diferencias significativas entre los grupos etarios estudiados (A: < 1 año, B: 1–2 años, C: > 2 años). Los niños del grupo A presentaron una frecuencia de seropositividad de 23,91 %; los del grupo B, de 42,85 % y en los niños del grupo C fue del 56 %. Esto indica un incremento de la frecuencia de presentación a medida que aumentó la edad, debido probablemente a las mayores posibilidades de contactar con estados infectantes del parásito, ya que los caninos y el suelo se hallan frecuentemente infectados por huevos de T. canis. Los niños abandonados provienen de hogares carenciados, donde a las malas condiciones de higiene resultantes de la ausencia de red de agua y cloacal se le agrega la frecuente promiscuidad con caninos, lo cual propicia la presencia de parasitosis. Sumado a la condición de desamparo, esto produce un estado de máxima vulnerabilidad.

Toxocariasis, visceral larva migrans or parasitic granulosis is a disease distributed worldwide with high prevalence in tropical and temperate regions. The agents involved are: Toxocara canis (dog roundworms) and Toxocara cati (cat roundworms), the former being the most significant due to its frequency in humans18. The soil is the natural reservoir and source of infection where the eggs develop into infective stages (stage J2–J3)12, being able to remain viable for extended periods of one to three years32. In humans, the infection is transmitted via the oral route, by accidental ingestion of infective eggs from the fur of animals, consumption of poorly sanitized fruits or vegetables, soil-contaminated hands, geophagy or early stages of nematodes present in tissues of paratenic or transport hosts3,5,16,26,29,32.

Four clinical presentations are known: visceral larva migrans (VLM), with abscess formation in the organs23,34, allergic asthma and eczema6 among other manifestations; ocular larva migrans (OLM)12 without the characteristic eosinophilia; neurological toxocariasis30 with diverse manifestations such as dementia, meningo-encephalitis, myelitis, cerebral vasculitis, epilepsy, or optic neuritis15,19,30 and covert toxocariasis which occurs when the larva is found in striated muscles, with no or few, general and non-specific symptoms3. Several studies have determined the seroprevalence of toxocariasis in different clusters of people and geographical areas: children of low socioeconomic status, middle class, rural areas, indigenous people, developed countries with different pathologies, school age, kindergarten and 12 year-old children1,2,4,7–9,14,20–22,25,30,33. However, investigations on the prevalence of toxocariasis in children younger than 3 years of age are scarce38 and there are no publications on abandoned-institutionalized children or infant foundlings10,17,24,28,38. The terms abandoned-institutionalized children or infant foundlings refer to those children whose parents have moved away from them, leaving them on any site or to the care of an institution, due to economic, social or moral reasons. The de facto abandonment may be transient or permanent. This is how “the family, a social unit, is replaced by a foundling asylum”27,36.

The state of helplessness in the strict etymological sense is synonymous with neglect, with the subsequent waiver of all rights and duties of the child. This extreme situation that involves judicial action is at the same time a health concern due to the consequences associated with the growth and development of the child when separated from his family environment11.

The aim of this work was to determine the seroprevalence of toxocariasis in infant foundlings (abandoned or institutionalized) up to 3 years of age since they are considered to be at high risk for several diseases due to their orphanhood status that leaves them in a situation of maximum vulnerability.

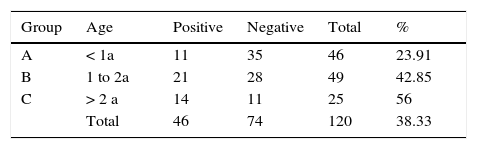

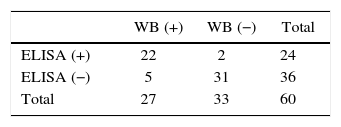

Materials and methodsStudy samples: Samples were obtained from 10-month to 3 year-old abandoned and institutionalized children. After the routine hematological testing performed on admission, the remaining serum was used in this study upon approval of the Instituto de Investigaciones Biomedicas / IRB Barcelona. A total of 120 samples were analyzed by ELISA. They were divided into three groups: A (<1 year old), B (1–2 years old) and C (>2 years old); 60 of them were randomly selected and analyzed by Western blot.

The ELISA test was performed using a commercial kit (Bordier Affinity products, Crissier 1013, Lausanne, Switzerland) in compliance with the manufacturer's instructions. The presence of parasite specific serum antibodies was detected with anti-human IgG-alkaline phosphatase conjugate on sensitized plates with T. canis excretory-secretory antigen.

Interpretation: Samples with an absorbance lower than that of the weak positive control serum were considered negative, while those with a higher absorbance were considered positive.

The Western blot assay was performed according to the technique used in the Department of Parasitology, National Institute of Infectious Diseases ANLIS “Dr. Carlos G. Malbrán”35.

Interpretation: It is considered positive when observing bands of 120, 70, 55, 30, 32 kDa and/or bands of 70 and 55 kDa.

For statistical analyses, Epidat 3.113 and Win Episcope 2.039 were used.

ResultsThe ELISA technique was used to analyze 120 serum samples, detecting a total of 46 seropositive children for T. canis IgG (38.33%) (Table 1).

After applying the test (chi-square = 7.77, p<0.05), there was a significant association between age and seroprevalence; the linear trend was also significant.

Only 60 of the 120 original samples were processed by Western blot, of which 27 (45%) showed the characteristic positive bands for T. canis (Table 2).

The differences observed between the two techniques are, since Westernblot technique presents 100% specificity, predictive value positive 93.3% and predictive value negative 100%. The kappa index (0.762) reported a strong correlation between the two techniques.

DiscussionToxocariasis is a cosmopolitan parasitic infection observed primarily in childhood, with little recognition as a public health problem. Different authors used the ELISA test for serological diagnosis of toxocariasis. In Resistencia, a subtropical region of Argentina, a seropositivity of 37.9% in children aged 1–14 was observed2. In the same area, a prevalence of 67% among individuals with similar age and high eosinophilia25 was reported as well as a prevalence of 20% in children younger than 14 years old from a rural community of Argentina8,31. Taranto et al.37 reported a positivity of 22.1% in an indigenous population of the northern province of Salta. In the province of Buenos Aires, a positivity of 17% and 36% was observed in children up to 12 years old from an urban and suburban area respectively32. In two regions of Spain, a seroprevalence of 0% and 4.2% was found in children from Madrid and Tenerife respectively9. In the same country, a prevalence of 0% vs. 37% was reported in middle class infants, aged 2–5 years old, in contrast with others of the same age but socially disadvantaged in Iran9, using two kinds of ELISA assays, in which frequencies of 11 and 25% respectively were observed, in children ranging from one month to 30 months of age, without significant differences regarding age. However, this study found that 38.33% of children were positive for T. canis using the ELISA technique and 36.66 % using Western blot. Significant differences among groups A, B and C were also observed. In this research, children in group A showed 23.91% of seropositivity, group B 42.85% and group C 56%, which indicates an increase in the frequency of occurrence as age advances, probably due to greater chances of contact with the parasite infective stages. As stated before, canines and soil are very often infected with T. canis16,28,40.

Not all individuals are equally likely to get infected or die, but for some, this alternative is greater. Abandoned children also belong to deprived households where as previously mentioned16,28, poor hygienic conditions resulting from lack of water and sewage networks and frequent promiscuity with canines, favor the presence of parasitic diseases. These, coupled with the condition of helplessness, cause a state of high vulnerability. This situation is reflected in the results obtained in this research in infants.

The bibliographic research conducted does not reveal any studies on seroprevalence of toxocariasis in the area of abandoned or institutionalized children. The results herein obtained showed that the determination of this disease should be included in routine hematology tests when admitted to an institution, especially in the case of abandoned children under the age of 3, considering that, as they are very young, the possibility of having contracted the disease might affect not only their physical and mental integrity but also their future growth, maturation and cognitive development or even lead to fatal consequences.

Ethical responsabilitesProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.