Technological developments have enabled the expansion of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) indications for more challenging clinical and angiographic scenarios. Our objective was to evaluate the results of PCI in two different periods in the past 6 years.

MethodsThis was a multicenter registry including 6,288 consecutive patients treated by PCI, who were divided according to different treatment periods: 2006 to 2008 (P1; n=1,779) and 2009 to 2012 (P2; n=4,509). We intended to compare the rates of in-hospital major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) and identify their predictors.

ResultsP2 patients were younger and had a higher prevalence of smoking and diabetes. These patients had a greater rate of multivessel, thrombotic and bifurcation lesions. The number of diseased vessels per patient was higher in the P2 Group, as well as the number of stents per patient, and the use of drug-eluting stents. MACCE was more frequent in P2 patients (2.5% vs. 3.5%; P=0.04), due to periprocedural myocardial infarction (1.7% vs. 2.6%; P=0.05), and there were no differences in terms of death (1.0% vs. 1.0%; P=0.87), stroke (0.2% vs. 0.1%; P=0.47) or emergency coronary artery bypass grafting (0.1% vs. 0; P=0.68). Age (odds ratio – OR – 1.02; 95% confidence interval – CI 95% – 1.00-1.05; P=0.04) and Killip III/IV (OR=6.0, 95% CI; 3.3-10.9; P<0.01) were the variables that best explained the presence of MACCE.

ConclusionsIn this large cohort, substancial changes occurred in the characteristics of patients treated by PCI in the last 6 years. This more complex scenario was associated to a slight increase of periprocedural myocardial infarctions, but not to other in-hospital clinical adverse events.

Mudanças no Perfil Populacional e Resultados daIntervenção Coronária Percutânea do Registro Angiocardio

IntroduçãoA evolução tecnológica tem permitido ampliar a indicação da intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) para cenários clínicos e angiográficos mais desafiadores. Nosso objetivo foi avaliar os resultados da ICP em dois diferentes períodos, nos últimos 6 anos.

MétodosRegistro multicêntrico no qual 6.288 pacientes consecutivos tratados por ICP foram divididos por períodos de tratamento: 2006 a 2008 (P1; n=1.779) e 2009 a 2012 (P2; n=4.509). Buscamos comparar as taxas de eventos cardíacos e cerebrovasculares adversos maiores (ECCAM) hospitalares e identificar seus preditores.

ResultadosPacientes do Grupo P2 mostraram ser mais jovens com maior prevalência de tabagismo e diabetes. Esses pacientes mostraram maior acometimento de múltiplos vasos, maior número de lesões trombóticas e lesões em bifurcações. A relação de vasos tratados/paciente foi maior no Grupo P2, assim como a relação stent/paciente e a utilização de stents farmacológicos. ECCAM foi mais frequente no Grupo P2 (2,5% vs. 3,5%; P=0,04), às custas do infarto periprocedimento (1,7% vs. 2,6%; P=0,05), não havendo diferenças quanto a óbito (1,0% vs. 1,0%; P=0,87), acidente vascular cerebral (0,2% vs. 0,1%; P=0,47) ou cirurgia de revascularização de emergência (0,1% vs. 0; P=0,68). Idade (odds ratio – OR – de 1,02; intervalo de confiança de 95% – IC 95% – de 1,00-1,05; P=0,04) e Killip III/IV (OR=6,03, IC 95%; 3,39-10,90; P<0,01) foram as variáveis que melhor explicaram a presença de ECCAM.

ConclusõesNessa grande coorte mudanças substanciais ocorreram nas características de pacientes tratados por ICP nos últimos 6 anos. O cenário mais complexo associou-se a discreto aumento de infartos periprocedimento mas não a outros eventos adversos clínicos hospitalares

Since the performance of the first balloon-catheter angioplasty, in 1977, at Andreas Gruentzigat Zurich University,1 percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has advanced significantly. Over the past 20 years, the development of materials, image acquisition, and technical improvement has allowed excellent results, establishing the percutaneous intervention as the firstline treatment in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) with ST-segment elevation,2,3 which can be indicated for all clinical forms and anatomical variations of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).4−6

The advances in interventional cardiology have promoted a change in the profile of patients undergoing percutaneous therapy. Currently, PCI is increasingly used in patients with more comorbidities and more complex CAD.4,5,7

The change in the clinical profile of patients over the years can influence the outcomes after PCI in randomised clinical trials, as well as in registries.4,8 The aim of the present study was to verify the evolutionary differences of the clinical, angiographic, and procedural profile, as well as in-hospital outcomes of patients undergoing PCI in the last six years of the Angiocardio Registry.

METHODSPopulationFrom August 2006 to October 2012, 6,288 consecutive patients underwent PCI at the centers that constitute the Angiocardio Registry (Hospital Bandeirantes, Rede D’Or São Luiz Analia Franco and Hospital Leforte, in São Paulo, SP, Brazil; Hospital Vera Cruz, in Campinas, SP, Brazil; and Hospital Regional do Vale do Paraíba, in Taubaté, SP, Brazil). Data were prospectively collected and stored in a computerized database available through the Internet in all centres participating in the registry. The analysis was performed in two periods: the first period (P1) was from 2006 to 2008 and included 1,779 patients; the second period (P2) was from 2009 to 2012 and included 4,509 patients. The primary objective was to compare the rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), comprising in-hospital death, periprocedural myocardial infarction, stroke, and emergency coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) at the time of hospital discharge between the determined periods.

ProcedureThe interventions were almost always performed via femoral access; the radial approach was used as an option in a few cases. The choice of technique and material used during the procedure were at the surgeon’s discretion, as was the assessmentof the need for glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Unfractionated heparin was used in the start of procedure at a dose of 70 U/kg to 100 U/kg, except in patients who already used low-molecular-weight heparin.

All patients received antiplatelet therapy combined with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), at loading doses of 300mg and maintenance dose of 100mg/day to 200mg/ day, and clopidogrel at loading doses of 300mg to 600mg and maintenance dose of 75mg/day. Femoral sheaths were removed fourhours after the start of heparinization. Radials sheaths were removed immediately after the procedure.

Angiographic analysis and definitionsAnalyses were performed on at least two orthogonal projections by experienced professionals, using digital quantitative angiography. This study used the angiographic criteria found in National Center of Cardiovascular Interventions (Central Nacional de Intervenções Cardiovasculares – CENIC) database of Brazilian Society of Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology (Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista – SBHCI). The type of lesion was classified according to the criteria of American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA).9 The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI)10 classification was used to determine pre- and post-procedural coronary flow. Procedural success was defined as achievement of angiographic success (residual stenosis<30 % with TIMI 3 flow) and absence of MACCE, comprising death, periprocedural myocardial infarction, stroke, and emergency CABG.11

Deaths from any cause were recorded and cardiac mortality was defined as that resulting from cardiogenic shock, heart failure, AMI, cardiac rupture, arrhythmia, or sudden death during hospital stay. Periprocedural infarction was defined by the reappearance of angina symptoms, with the presence of electrocardiographic alterations (new ST-segment elevation or new Q waves) and/or angiographic evidence oftarget vessel occlusion. Emergency CABG was considered when performed immediately after PCI.

Statistical analysisThe data stored in the Oracle-based database were plotted in Excel spreadsheets and analyzed using SPSS version 15.0. The continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentiles. Associations between continuous variables were evaluated using the ANOVA model. The associations between categorical variables were evaluated by the chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test, or likelihood ratios, when appropriate. Significance level was set at P<0.05. Single and multiple logistic regression models were applied to identify predictors of MACCE.

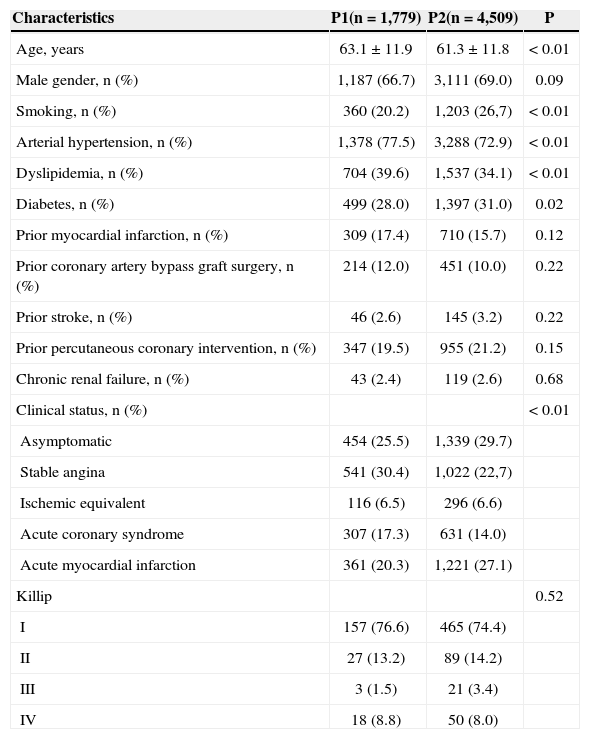

RESULTSThe clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The group treated in the more recent period (P2) was found to be, on average, two years younger, with higher prevalence of smokers and diabetics, and lower prevalence of arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, and prior CABG. It also showed a greater number of asymptomatic patients or those with AMI with ST-segment elevation.

Clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | P1(n=1,779) | P2(n=4,509) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.1±11.9 | 61.3±11.8 | < 0.01 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 1,187 (66.7) | 3,111 (69.0) | 0.09 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 360 (20.2) | 1,203 (26,7) | < 0.01 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 1,378 (77.5) | 3,288 (72.9) | < 0.01 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 704 (39.6) | 1,537 (34.1) | < 0.01 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 499 (28.0) | 1,397 (31.0) | 0.02 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 309 (17.4) | 710 (15.7) | 0.12 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery, n (%) | 214 (12.0) | 451 (10.0) | 0.22 |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 46 (2.6) | 145 (3.2) | 0.22 |

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | 347 (19.5) | 955 (21.2) | 0.15 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 43 (2.4) | 119 (2.6) | 0.68 |

| Clinical status, n (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 454 (25.5) | 1,339 (29.7) | |

| Stable angina | 541 (30.4) | 1,022 (22,7) | |

| Ischemic equivalent | 116 (6.5) | 296 (6.6) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 307 (17.3) | 631 (14.0) | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 361 (20.3) | 1,221 (27.1) | |

| Killip | 0.52 | ||

| I | 157 (76.6) | 465 (74.4) | |

| II | 27 (13.2) | 89 (14.2) | |

| III | 3 (1.5) | 21 (3.4) | |

| IV | 18 (8.8) | 50 (8.0) |

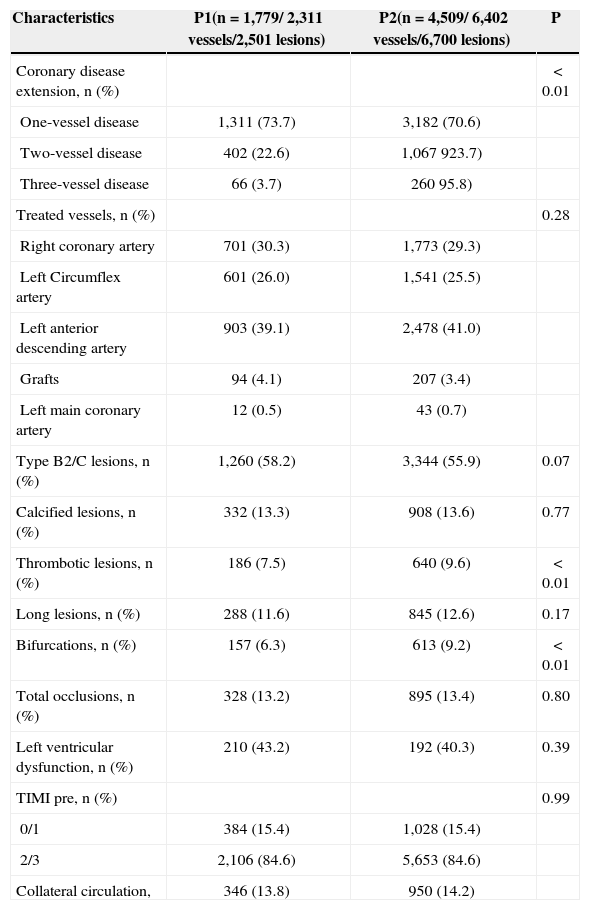

From the angiography point of view, patients in the P2 group had a more complex profile, with a higher rate of multivessel involvement, and a higher number of thrombotic and bifurcation lesions (Table 2).

Angiographic Characteristics

| Characteristics | P1(n=1,779/ 2,311 vessels/2,501 lesions) | P2(n=4,509/ 6,402 vessels/6,700 lesions) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary disease extension, n (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| One-vessel disease | 1,311 (73.7) | 3,182 (70.6) | |

| Two-vessel disease | 402 (22.6) | 1,067 923.7) | |

| Three-vessel disease | 66 (3.7) | 260 95.8) | |

| Treated vessels, n (%) | 0.28 | ||

| Right coronary artery | 701 (30.3) | 1,773 (29.3) | |

| Left Circumflex artery | 601 (26.0) | 1,541 (25.5) | |

| Left anterior descending artery | 903 (39.1) | 2,478 (41.0) | |

| Grafts | 94 (4.1) | 207 (3.4) | |

| Left main coronary artery | 12 (0.5) | 43 (0.7) | |

| Type B2/C lesions, n (%) | 1,260 (58.2) | 3,344 (55.9) | 0.07 |

| Calcified lesions, n (%) | 332 (13.3) | 908 (13.6) | 0.77 |

| Thrombotic lesions, n (%) | 186 (7.5) | 640 (9.6) | < 0.01 |

| Long lesions, n (%) | 288 (11.6) | 845 (12.6) | 0.17 |

| Bifurcations, n (%) | 157 (6.3) | 613 (9.2) | < 0.01 |

| Total occlusions, n (%) | 328 (13.2) | 895 (13.4) | 0.80 |

| Left ventricular dysfunction, n (%) | 210 (43.2) | 192 (40.3) | 0.39 |

| TIMI pre, n (%) | 0.99 | ||

| 0/1 | 384 (15.4) | 1,028 (15.4) | |

| 2/3 | 2,106 (84.6) | 5,653 (84.6) | |

| Collateral circulation, | 346 (13.8) | 950 (14.2) |

TIMI=Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarctio

Regarding the procedural characteristics (Table 3), the ratio of treated vessels per patient was higher in the P2 group (1.3±0.6 vs. 1.4±0.7; P<0.01), as well as the stent/patient ratio (1.2±0.6 vs. 1.3±0.7; P=0.02) and the use of drug-eluting stents (10.9% vs. 25.1%; P<0.01). With respect to the dimensions of the implanted prostheses, they had greater diameter and length in the P2 group (2.94±0.45mm vs. 2.98±0.50mm; P<0.01 and 17.9±6.7mm vs. 18.9±7.1mm; P<0.01, respectively). Direct stenting was less commonly performed (52.3 % vs. 35.7%; P<0.01), and thrombus aspiration was more used in P2 group (0.8 % vs. 3.6%; P<0.01).

Characteristics of the procedures

| Characteristics | P1(n=1,799/2331 vessels / 2,501 vessels) | P2(n=4,509/6,042 vessels/ 6,700 vessels) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treated vessels/patient | 1.3±0.6 | 1.4±0.7 | < 0.01 |

| Stent use, n (%) | 1,681 (94.5) | 4,271 (94.7) | 0.76 |

| Stent/patient ratio, n (%) | 1.2±0.6 | 1.3±0.7 | 0.02 |

| Drug-eluting stents, n (%) | 229 (10.9) | 1,383 (25.1) | < 0.01 |

| Direct stenting technique, n (%) | 1,097 (52.3) | 1,966 (35.7) | < 0.01 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 2.94±0.45 | 2.98±0.50 | 0.01 |

| Stent length, mm | 17.9±6.7 | 18.9±7.1 | < 0.01 |

| Primary PCI, n (%) | 140 (7.9) | 459 (10.2) | < 0.01 |

| Rescue PCI, n (%) | 65 (3.7) | 137 (3.0) | 0.24 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, n (%) | 114 (6.4) | 339 (7.5) | 0.14 |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 14 (0.8) | 154 (3.6) | < 0.01 |

| TIMI post, n (%) | 0.30 | ||

| 0/1 | 55 (2.3) | 123 (1.9) | |

| 2/3 | 2,307 (97.7) | 6,203 (98.1) | |

| Degree of stenosis, n (%) | 0.02 | ||

| Pre | 83.6±12.3 | 82.9±13.1 | 0.02 |

| Post | 4.8±17.5 | 3.1±15.2 | < 0.01 |

| Procedural success, n (%) | 1,704 (95.8) | 4,299 (95.3) | 0.49 |

ICP=percutaneous coronary intervention PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

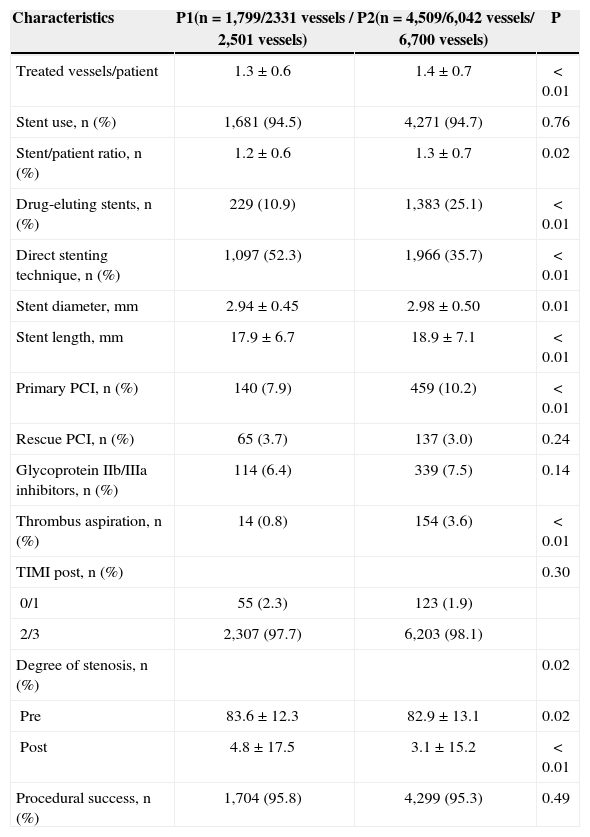

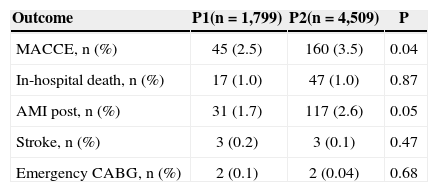

Table 4 shows the clinical outcome in the hospital phase. It was observed that MACCE was more frequent in the P2 group (2.5% vs. 3.5%; P=0.04) at the expense of periprocedural AMI (1.7 % vs. 2.6%; P=0.05), with no difference between groups regarding in-hospital deaths (1.0 % vs. 1.0%; P=0.87), stroke (0.2 % vs. 0.1%; P=0.47), or emergency CABG (0.1 % vs. 0%; P=0.68).

Clinical outcomes during hospitalisation

| Outcome | P1(n=1,799) | P2(n=4,509) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACCE, n (%) | 45 (2.5) | 160 (3.5) | 0.04 |

| In-hospital death, n (%) | 17 (1.0) | 47 (1.0) | 0.87 |

| AMI post, n (%) | 31 (1.7) | 117 (2.6) | 0.05 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 0.47 |

| Emergency CABG, n (%) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.04) | 0.68 |

MACCE=major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events AMI=acute myocardial infarction

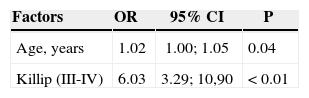

In the univariate analysis, the variables age; Killip functional class III/IV; multivessel involvement; lesions type B2/C; long, calcified or thrombotic lesions; occlusive lesions; TIMI flow 0/1 pre-PCI; presence of collateral circulation; primary PCI; and use of glycoprotein IIb/ IIIa inhibitors and thrombus aspiration showed a significant association with the occurrence of MACCE. In the multivariate analysis, age (odds ratio [OR]: 1.02; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 1.00-1.05; P=0.04) and Killip class III/IV (OR: 6.0; 95% CI; 3.3-10.9; P<0.01) were the variables that best explained the presence of in-hospital MACCE (Table 5).

DISCUSSIONThe observation of this daily clinical practice and the literature data have shown changes in the profile of patients treated with PCI over the years, resulting from technological developments of the procedure, and alterations in CAD epidemiology and risk factors. These changes have been very significant in registries that evaluate long periods, especially when including comparisons of intervention results before and after the introduction of stents, or even before and after the availability of drug-eluting stents. This contemporary registry demonstrated that differences might be found in a shorter period of time, as technological changes increase by geometric progression, which promotes the treatment of more clinically and angiographically complex patients.

In this study, patients from the most recent period (P2) were younger and showed a higher prevalence of smokers and diabetics. The occurrence of coronary heart disease among young people has increased over the years. The French registry FAST AMI showed a significant increase of AMI in young individuals in the last 15 years, in both males and (especially) in females.12 One of the observations that could explain this fact was the significant increase of obesity and smoking (as in the present registry). Previous Brazilian data also show this trend, as is the case of the Risk Factors Associated with Myocardial Infarction in Brazil (AFIR-MAR) study,13 which indicated the increase of AMI in younger patients and smokers. The presence of a higher number of diabetic patients in the second study period has an additional association with the increased supply of pharmacological stents in this period, providing a more effective approach with lower rates of restenosis in this population.14

The implementation of chest pain protocols in hospitals participating in the registry, with primary PCI availability 24 hours a day, may explain the growing number of this type of PCI in the present registry. Regarding the care of AMI, the rate of use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors remained stable and low (6.4 % to 7.5 %) during the study period, which has been a trend in literature since the advent of clopidogrel, new antiaggregants, and the use of thrombus aspiration catheters12 The more frequent use of aspiration catheters in the second period group coincides with the publication, in 2008, of the TAPAS trial results, which showed the superiority of thrombus aspiration technique to treat AMI with ST-segment elevation, reducing cardiac mortality combined with non fatal reinfarction within one year.15,16

The continuous improvement of the material used in the PCI, such as balloons and stents of better navigability and smaller calibre, guide wires with different characteristics of flexibility and stiffness, and drug-eluting stents, for instance, has increased the possibilities of using of the percutaneous technique in patients with greater angiographic complexity. This was also observed in the present study, with patients from P2 showing more severe coronary disease, such as multivessel involvement, thrombotic lesions, and diffuse (> 20mm) and bifurcation lesions, requiring the use of longer and pharmacological stents. This finding was also described by Cardoso et al.17 in an observational study based on the CENIC database.

While the technological advancement of materials and adjunct medications used in PCI aim to achieve better results, with high success rates and low rate of complications, this registry observed a tendency of slight increase in MACCE in recent years, probably due to the increasing complexity of patients undergoing PCI.

Study limitationsThe limitations of the present study were the retrospective analysis of data, its performance by a single group of interventionists, and the lack of longterm follow-up.

CONCLUSIONSIn this large cohort, there were substantial changes in clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics of patients treated by PCI from 2006 to 2012. The more complex scenario was associated with a slight increase in periprocedural infarctions, but not to other adverse in-hospital clinical events.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.