Cardiovascular and periodontal diseases are common inflammatory conditions. In atherosclerosis, inflammation plays a continuous role in the development, destabilization, and rupture of atheromas. There is controversial scientific evidence regarding the association between chronic periodontitis and coronary artery disease (CAD). The objective of this study was to assess the association between chronic periodontitis and CAD in this practice.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional controlled study of 206 patients with no prior CAD and for whom coronary angiography was indicated; the data included clinical history, physical examination and blood sample collection to test for blood glucose, lipid profile, and C-reactive protein levels. The presence of chronic periodontitis was determined by clinical examination performed by a periodontist. The levels of bacterial plaque, gingival calculus, bleeding, exudate, and classical signs of inflammation were recorded.

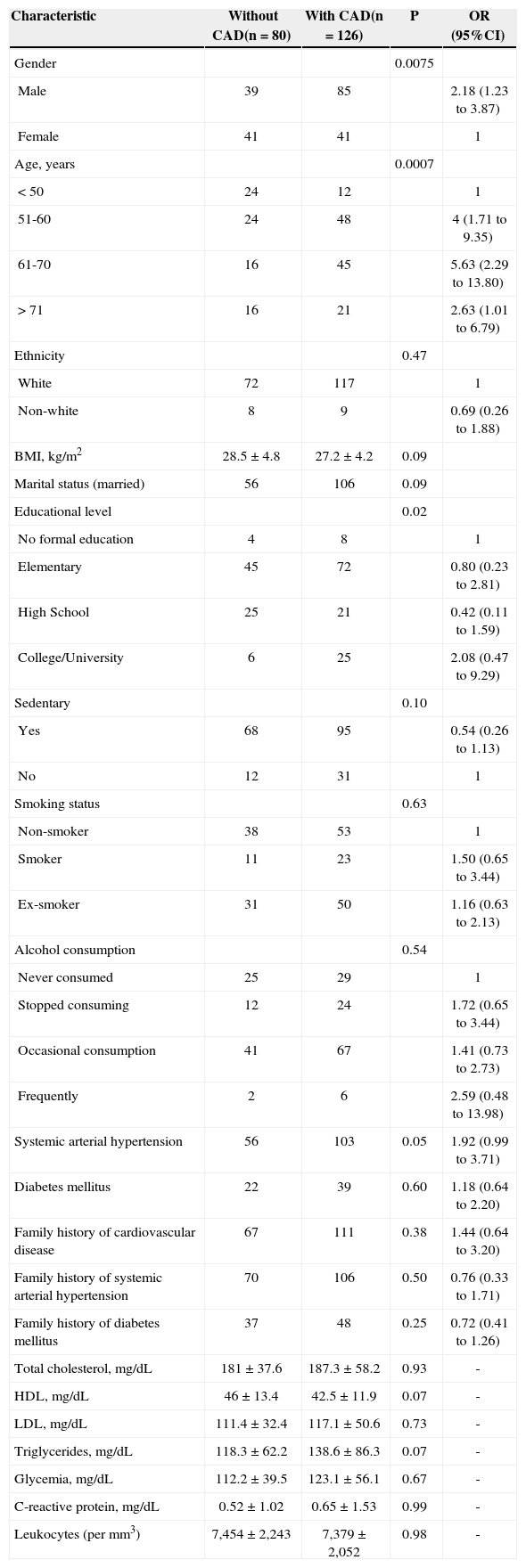

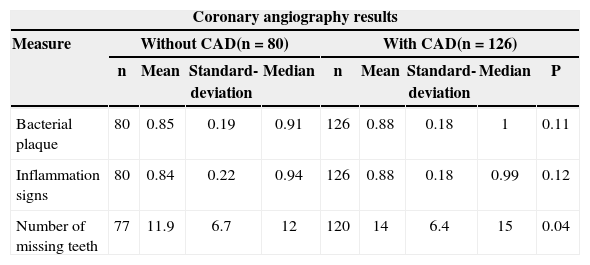

ResultsThe mean age was 60.3±10.1years, and 60.2% of the subjects were male. CAD was present in 126 patients (61.2%). There was an association between CAD and gender [male gender, odds ratio (OR) 2.18; P=0.0075], age (61–70 years, OR 5.63; P=0.0007), and educational level (higher educational level, OR 2.08; P=0.02). Inflammatory biomarkers did not differ between the groups with and without CAD. Signs of inflammation and bacterial plaque were present in 88% of patients with CAD, slightly higher than the rate observed in patients without CAD. Poor oral health, as indicated by the loss of teeth, was more prevalent in patients with CAD. The number of missing teeth was 14±6.4 and 11.9±6.7 (P=0.04) in patients with and without CAD, respectively.

ConclusionsThere is an association between poor oral health and CAD.

Associação entre Saúde Bucal e Doença Arterial Coronária Aterosclerótica em Pacientes Submetidos a CineangiocoronariografiaEstudo Transversal Controlado

IntroduçãoDoenças cardiovasculares e periodontais são condições inflamatórias comuns na população. Na aterosclerose, a condição inflamatória tem papel contínuo no desenvolvimento, desestabilização e ruptura da placa do ateroma. Existe evidência científica controversa em relação à associação entre periodontite crônica e doença arterial coronária (DAC). O objetivo do estudo foi verificar a associação entre periodontite crônica e DAC em nosso meio.

MétodosEstudo transversal controlado, com amostra de 206 pacientes sem DAC prévia e com indicação clínica de cineangiocoronariografia, submetidos a anamnese, exame físico e coleta de sangue para verificação de glicemia, perfil lipídico e proteína C-reativa. A presença de periodontite crônica foi determinada por exame clínico realizado por periodontista, buscando avaliar quantidade de placa bacteriana, cálculos gengivais, sangramento, exsudato e sinais clássicos de inflamação.

ResultadosA média de idade foi de 60,3±10,1 anos e 60,2% eram do sexo masculino. DAC esteve presente em 126 pacientes (61,2%). Houve associação da presença de DAC com gênero [sexo masculino, odds ratio (OR) 2,18; P=0,0075], idade (61–70 anos, OR 5,63; P=0,0007) e escolaridade (ensino superior, OR 2,08; P=0,02). Os biomarcadores inflamatórios não diferiram entre os grupos com e sem DAC. Sinais inflamatórios e placa bacteriana ocorreram em 88% dos pacientes com DAC, índice ligeiramente superior ao observado naqueles sem DAC. Má saúde bucal, representada por perda de dentes, foi mais prevalente nos pacientes com DAC. O número de dentes faltantes foi de 14±6,4 e de 11,9±6,7 (P=0,04) nos pacientes com e sem DAC, respectivamente.

ConclusõesHá associação entre saúde bucal comprometida e DAC.

Coronary heart disease due to atherosclerosis accounts for most deaths from cardiovascular disease. Its pathophysiology is multifactorial and includes the response to injury and immuno-inflammatory, lipogenic, and infectious mechanisms. Many risk factors, such as family history, male gender, older age, obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and smoking have been linked to the development of atherosclerosis and its complications. However, some cases of ischemic heart disease are not explained by these factors.1

Poor oral hygiene is the main cause of chronic periodontitis.2 A low frequency of tooth brushing and lack of flossing result in specific bacterial plaque build-up around one or more teeth, which leads to gum inflammation. In a genetically susceptible patient, this inflammation leads to the development of chronic periodontitis, which is characterized by support epithelial migration towards the root surface followed by loss of support tissue and alveolar bone, culminating in the loss of the dental element.3

Chronic periodontitis is an infection caused by Gram-negative bacteria, which find an ideal habitat in the periodontal pockets.3 The association between chronic periodontitis and cardiovascular disease can be explained by different pathophysiological mechanisms involving both microbial and inflammatory factors,4 as well as other shared known risk factors.5

In recent decades, the interest in establishing an association between inflammatory conditions, oral health, and ischemic heart disease has increased.6 Previous studies have determined the role of inflammation and its biomarkers in cardiovascular disease.7 In this context, chronic periodontitis, one of the most prevalent infections, has emerged as a possible modifiable factor in systemic inflammatory conditions.8 This has been observed, for instance, in the increases in C-reactive protein levels,9 which is an important prognostic marker of cardiovascular risk.7 However, these studies were not conclusive due to a lack of homogeneity in chronic periodontitis assessment and the presence of other confounding variables, such as smoking.10–13 Therefore, the association between chronic periodontitis and coronary artery disease remains inconclusive.

Given the importance of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease and chronic periodontitis with regard to public health, the ease of assessing the clinical signs of chronic periodontitis, and the availability of a recognized method for the evaluation of coronary artery disease (coronary angiography), this study aimed to clarify the association between oral health and coronary lesions.

METHODSThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Instituto de Cardiologia do Rio Grande do Sul and Centro de Pesquisas Odontológicas São Leopoldo Mandic (Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil).

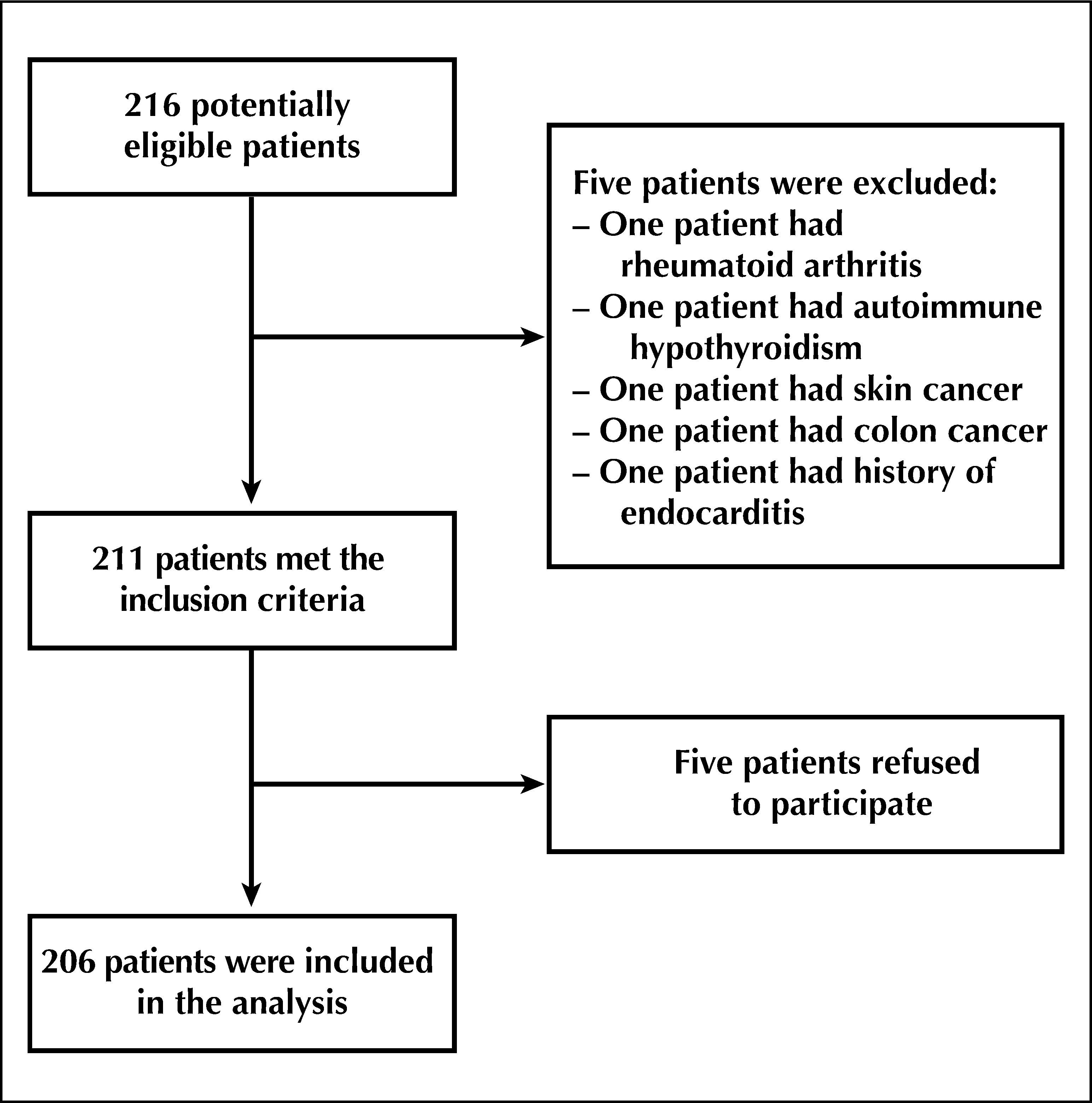

A controlled cross-sectional study was performed using a sample of 216 patients; the data were collected from March, 2010 to May, 2011 at the Instituto de Cardiologia do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Individuals with a medical indication for coronary angiography were invited to participate in the study; all signed an informed consent. The sample consisted of patients aged 18 years and older. The exclusion criteria included the use immunosuppressive drugs, the presence of autoimmune or neoplastic diseases, a history of infective endocarditis, and pregnancy or lactation.

The patients were then evaluated through a clinical history and structured physical examination. Data collected from these examinations included demographic and anthropometric information, family history, and associated diseases. The presence of chronic periodontitis was determined by clinical examination that included visual and tactile inspection performed by a periodontist. The periodontist evaluated the amount of plaque, gingival calculus, bleeding, and exudate, and searched for signs of inflammation. Subsequently, blood glucose, lipid profile, and ultrasensitive C-reactive protein levels were assessed. All patients underwent coronary angiography performed by one of two cardiologists blinded to the periodontal examination and laboratory results to determine the presence of coronary atherosclerosis, which was defined according to the ACC National Cardiovascular Data Registry.14

Statistical analysisThe sample size of this study was based on a previous study.15 Chronic periodontitis was observed in 76% (85/116) of patients with coronary artery disease and in 53% (20/38) of patients with normal coronary arteries. Considering a significance level of 5%, test power of 80%, and a difference of 25% in the prevalence of chronic periodontitis between healthy individuals and those with coronary artery disease, the required sample size was 196 patients. Initially, all of the variables were evaluated descriptively by calculating the absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies, and in the case of the continuous variables, by calculating the mean, standard deviation, median, and minimum and maximum values. To study the association of categorical variables with the response variable, each variable was studied bivariately by calculating the odds ratio (OR) and its confidence interval and using the chi-squared test (or Fisher’s exact test, when there was a value < 5). The differences in the means of the continuous variables between the groups were evaluated using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney’s test or the Mann–Whitney test. The level of significance was set at 5%, and the software used for the analysis was SAS version 9.2.

RESULTSOf the total 216 patients who were potentially eligible for the study, five were eliminated by the exclusion criteria and five refused to participate. Thus, 206 patients were analysed in the study (Figure 1).

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics and the presence of inflammatory markers and risk factors for atherosclerosis in patients with and without coronary artery disease. Coronary artery disease was diagnosed in 61.2% of patients. The mean age was 60.3±10.1years, and 60.2% of the participants were male. Gender, age > 50 years, and educational level were associated with the presence of coronary artery disease. The presence of elevated inflammatory biomarkers was not associated with these variables.

Demographic and Anthropometric Characteristics and Risk Factors for Coronary Disease, Inflammatory Markers and Associated Diseases

| Characteristic | Without CAD(n=80) | With CAD(n=126) | P | OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.0075 | |||

| Male | 39 | 85 | 2.18 (1.23 to 3.87) | |

| Female | 41 | 41 | 1 | |

| Age, years | 0.0007 | |||

| < 50 | 24 | 12 | 1 | |

| 51-60 | 24 | 48 | 4 (1.71 to 9.35) | |

| 61-70 | 16 | 45 | 5.63 (2.29 to 13.80) | |

| > 71 | 16 | 21 | 2.63 (1.01 to 6.79) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.47 | |||

| White | 72 | 117 | 1 | |

| Non-white | 8 | 9 | 0.69 (0.26 to 1.88) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.5±4.8 | 27.2±4.2 | 0.09 | |

| Marital status (married) | 56 | 106 | 0.09 | |

| Educational level | 0.02 | |||

| No formal education | 4 | 8 | 1 | |

| Elementary | 45 | 72 | 0.80 (0.23 to 2.81) | |

| High School | 25 | 21 | 0.42 (0.11 to 1.59) | |

| College/University | 6 | 25 | 2.08 (0.47 to 9.29) | |

| Sedentary | 0.10 | |||

| Yes | 68 | 95 | 0.54 (0.26 to 1.13) | |

| No | 12 | 31 | 1 | |

| Smoking status | 0.63 | |||

| Non-smoker | 38 | 53 | 1 | |

| Smoker | 11 | 23 | 1.50 (0.65 to 3.44) | |

| Ex-smoker | 31 | 50 | 1.16 (0.63 to 2.13) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.54 | |||

| Never consumed | 25 | 29 | 1 | |

| Stopped consuming | 12 | 24 | 1.72 (0.65 to 3.44) | |

| Occasional consumption | 41 | 67 | 1.41 (0.73 to 2.73) | |

| Frequently | 2 | 6 | 2.59 (0.48 to 13.98) | |

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 56 | 103 | 0.05 | 1.92 (0.99 to 3.71) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 | 39 | 0.60 | 1.18 (0.64 to 2.20) |

| Family history of cardiovascular disease | 67 | 111 | 0.38 | 1.44 (0.64 to 3.20) |

| Family history of systemic arterial hypertension | 70 | 106 | 0.50 | 0.76 (0.33 to 1.71) |

| Family history of diabetes mellitus | 37 | 48 | 0.25 | 0.72 (0.41 to 1.26) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 181±37.6 | 187.3±58.2 | 0.93 | - |

| HDL, mg/dL | 46±13.4 | 42.5±11.9 | 0.07 | - |

| LDL, mg/dL | 111.4±32.4 | 117.1±50.6 | 0.73 | - |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 118.3±62.2 | 138.6±86.3 | 0.07 | - |

| Glycemia, mg/dL | 112.2±39.5 | 123.1±56.1 | 0.67 | - |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | 0.52±1.02 | 0.65±1.53 | 0.99 | - |

| Leukocytes (per mm3) | 7,454±2,243 | 7,379±2,052 | 0.98 | - |

CAD=coronary artery disease; HDL=high-density lipoprotein; CI=confidence interval; BMI=body mass index; LDL=low-density lipoprotein; n=number of patients; OR=odds ratio.

Table 2 shows the association between the assessed measures of oral health and the coronary angiography results. The presence of bacterial plaque and inflammatory signs were not associated with coronary artery disease. Most patients with and without atherosclerotic lesions had loss of teeth (95%, 197/206). The mean number of missing teeth was 14±6.4 in patients with atherosclerosis and 11.9±6.7 in patients without atherosclerotic lesions. An association between the number of missing teeth and coronary artery disease as detected by angiography was observed (P=0.04).

Association between Oral Health Measures and Coronary Angiography Results

| Coronary angiography results | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Without CAD(n=80) | With CAD(n=126) | |||||||

| n | Mean | Standard-deviation | Median | n | Mean | Standard-deviation | Median | P | |

| Bacterial plaque | 80 | 0.85 | 0.19 | 0.91 | 126 | 0.88 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.11 |

| Inflammation signs | 80 | 0.84 | 0.22 | 0.94 | 126 | 0.88 | 0.18 | 0.99 | 0.12 |

| Number of missing teeth | 77 | 11.9 | 6.7 | 12 | 120 | 14 | 6.4 | 15 | 0.04 |

CAD=coronary artery disease; n=number of patients.

Initially, this study showed a high prevalence of clinical signs of chronic periodontitis. When compared to another study carried out in a third-world population, a three-fold higher prevalence tooth loss was observed.16 The authors believe that this difference is due to the characteristics of the sample, which consisted of individuals of low socio-economic status and older mean age. Previous studies have shown a high prevalence of chronic periodontitis in older17 and low-income18 patients, although there have been no studies that specifically assessed the association between socioeconomic status and chronic periodontitis, and their impact on coronary artery disease.6

The association between chronic periodontitis and coronary artery disease is controversial. While some studies have not identified an association,10,19–21 others have shown the opposite.12,13,22 More recent meta-analyses have indicated the existence of this association.11,23,24 However, the included studies had small samples or lacked accurate diagnostic criteria for chronic periodontitis and coronary artery disease. Many of these criteria are not validated, and the studies did not control for risk factors common in both conditions. The present study demonstrates that there is an association between poor oral health, represented by a higher number of missing teeth, and the presence of coronary artery disease. In a recent meta-analysis, there was a 1.24-fold increase in the risk for coronary artery disease in patients with fewer than ten teeth.15 A Scottish study in 2010 showed that the simple act of tooth brushing twice a day decreased the risk of a cardiovascular event by 40% and reduced serum levels of C-reactive protein compared tooth brushing once a day.2 The loss of two dental elements can be indicative of an individual’s cumulative history of chronic periodontitis and of the time of exposure to the disease.25

The present study excluded totally edentulous patients but included patients with at least six teeth present. In one mouth with few teeth and visible signs of inflammation, such as oedema, bleeding, and suppuration on probing of the periodontal pockets, it became evident that the loss of teeth may have been due to chronic periodontitis. Bleeding upon probing, for instance, reflects chronic periodontitis and ulceration of the periodontal pocket epithelium, which, in turn, reflects the release of systemic markers due to tissue invasion and the dissemination of micro-organisms.25

The present study sought to rule out possible confounders for these results. The diagnosis of coronary artery disease was established by coronary angiography, which is considered the diagnostic gold standard. In contrast to previous studies, the possibility of bias from confounding risk factors such as smoking, sedentary life-style, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus was eliminated in the present study, as their distribution was similar between the groups with and without coronary artery disease. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in the serum levels of inflammatory markers in patients with or without coronary artery disease, although previous studies have already demonstrated this association.7

Study limitationsThe present study has limitations. The high prevalence of chronic periodontitis in the population that uses the public health system, which includes individuals of low socio-economic status and greater age, may have influenced the analysis of the association between coronary artery disease and oral health.

CONCLUSIONSAn association between poor oral health, represented by missing teeth, and coronary artery disease was demonstrated in the present study. Tooth loss is an indicator of chronic periodontitis, suggesting its association with coronary artery disease.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the Fundo de Apoio à Pesquisa do Instituto de Cardiologia do Rio Grande do Sul/FUC para Ciência e Cultura (FAPICC) for the financial support given to this study.