The family has been seen over the years and in the historical evolution of humans as the essential unit of which societies are formed and structured. It is considered the original cell of life in society and the cradle of education that favours the learning and potential development of its members. Domestic violence encompasses verbal abuse, physical or emotional abuse, intimidation, sexual abuse or financial control. We studied domestic violence in the Bolivarian population, looking at couple relationships and the repercussions on the family members in terms of the education and performance of the children in their care.

MethodsSurveys were applied in the cantons of San Miguel, San José de Chimbo and Guaranda.

ResultsIt was found that disputes in families are caused mainly by financial situations (19%) and jealousy (24%), and that they are witnessed by the children, with shouting being the predominant form. From the point of view of the children, fear (29%) is the outstanding feeling for those who have witnessed family fights.

ConclusionsShouting is the predominant form of arguments between couples, with finances, jealousy and alcohol consumption being the most common causes of family disputes. In children who witness these forms of behaviour, a feeling of fear or dread predominates.

La familia es vista a través de los años y en la evolución histórica del hombre como la unidad esencial en que se conforman y estructuran las sociedades. Se la considera la célula original de la vida en sociedad y cuna de la educación que favorece el aprendizaje y el desarrollo potencial de sus miembros. La violencia intrafamiliar abarca ofensas de palabra, daño físico o psíquico, intimidación, abuso sexual o control económico. En el presente trabajo se estudió el comportamiento que la violencia intrafamiliar tiene en la población bolivarense, atendiendo a las relaciones de pareja y la repercusión que implica para sus integrantes respecto a la formación y la actuación de los menores a su cuidado.

MétodosSe aplican encuestas en los cantones de San Miguel, San José de Chimbo y Guaranda.

ResultadosSe reveló que en las familias ocurren disputas ocasionadas preferentemente por situaciones económicas (19%) y por celos (24%), que los menores presencian; la manifestación de gritos es la forma predominante en estas. Respecto a los menores, es el miedo (29%) el sentimiento sobresaliente para quienes han presenciado peleas familiares.

ConclusionesLos gritos son la forma predominante de discusiones entre las parejas, y las causas más frecuentes de las disputas familiares son el factor económico, los celos y el consumo de alcohol. En los menores que presencian estas formas de comportamiento predomina un sentimiento de temor o miedo.

From very early studies, the family is identified as a group of people with blood links, resulting from marital or cohabiting relationships and legal and emotional ties, as Parra1 affirms in her research regarding the topic. Méndez2 states that the family is made up of groups of people in whom social and cultural values inherited from their ancestors are reproduced.

In general, the family has been seen over the years and in the historical evolution of humans as the essential unit in which societies are shaped and structured. It is the structure which maintains the basic role of establishing the support for emotional and physical development and the well-being of its members. It has signified the core for economic progression by organising a social unit united around common interests and goals. As part of the responsibilities and goals that make it up, it includes fostering the learning and development of its members.3 As defined by the United Nations General Assembly,4 the family is considered to be the natural and fundamental element of society, with a right to the protection of its integrity by society and the State.

The family is assigned the responsibility of training its members, their social behaviour and the successful performance of its members, which is associated with robust, solid and stable families.5

Furthermore, domestic violence is understood as the action of any family member against any of its members in the family home, against their will or desire. It includes verbal, physical or psychological abuse, intimidation, sexual abuse or financial control. Salas6 states that the appearance of any of the mentioned forms of behaviour with the intention to control, bring down or overshadow the will of any member of the family circle is a palpable manifestation of domestic violence. According to Navarro7 and Rodríguez,8 gender-based violence in current society has educational implications, social and psychological effects and historical elements that differ over time.

Since the end of the last century, there has been an interest in the topic of violence against women, which has been undertaken in studies carried out by international organisations. In November 1985, the first resolution on this problem was approved by the United Nations General Assembly. In particular, the situation of adult women who live with domestic violence in Latin America is referred to, for which it is estimated that these incidents are only reported in 15–20% of cases.9

Sagot10 states, in her study carried out in 10 Latin American countries regarding the laws that punish this type of aggression that, although there are laws in Ecuador, they do not consider any redress for the harm suffered. The influence of conciliation hearings, in which the position of women is undermined, are criticised. Furthermore, the existence of positive social responses in the face of domestic violence are noteworthy, such as working initiatives in some spaces, among which there are Ecuadorian communities, and recent studies verify the growth in the number of reports received at Women and Family Police Units, although these still do not reliably reflect everything that is happening.11

It is well known that, historically, Ecuador has followed a slow process to achieve gender equality in society, and the 2008 Constitution describes the principles and rights in favour of reaching such goals, which was ratified by the National Assembly of Ecuador in 2016.12

In the Plan Nacional para el Buen Vivir [National Plan for Good Living] (PNBV),13 drawn up by the Ecuadorian government as a guide for action in its social projects, the following is proposed as part of the assessment for objective 2: "back equality, cohesion, inclusion and social and territorial equality in diversity", the need to prevent, eradicate and punish those who violate or infringe on gender rights, in both individual and collective actions, whether in the private and/or public sphere. As part of the Strategic Policies and Guidelines (clause g), the need to develop and implement strategies for "…the closure of inequality gaps, with an emphasis on the guarantee of rights, gender, intergenerational and intercultural equality" is stated explicitly.

The research carried out by Camacho14 is present in the results of national research. Camacho illustrates that the incidence of violence towards women in Ecuador varies according to the region of the country, and that Sierra (Mountainous Region) and Amazonía (Amazon Region) are the areas with the highest percentages. Boira15 identifies as predominant forms of manifestation the types of physical and psychological violence, despite recognising the existence of possible pressures so that these attitudes are not reported and, in a subsequent article about the Imbabura region,16 he acknowledges the need for and recommends studies which allow for accurate and up-to-date information on domestic violence to be made available, which will reward the performance of coordinated and integral actions as an element in favour of violence prevention.

As a specific background to the work that is presented, the study by Viera et al.17 identifies domestic violence in particular in the province of Bolívar, Ecuador, where the causes of partner abuse include alcohol consumption, male chauvinism predominant in the culture of families in the region and having been abused at some point during childhood, primarily males.

From the considerations referred to and given the importance that a satisfactory and harmonious space for living together has on the psychosocial development of the young generation, studying the behaviour that domestic violence has on the population of Bolívar, addressing the partner relationships and the impact that for its members implies respect for the training and action of children in their care was taken as an objective of interest.

MethodsThe study carried out is exploratory and in a survey format, which is considered appropriate because it enables the understanding of human behaviour, which is of greater interest in the description of social experiences for this study. For the collection of the correspondence data, the items of interest were determined. It was kept in mind to use questions which are easy to understand, brief, written in affirmative word order and with exclusive responses. The survey was validated by two experts not involved in the project. It is worth noting that, before their application, the students were trained by teachers in how to proceed with the population: the friendly way to approach the population, while identifying who was questioning them and guaranteeing their anonymity.

The population of the districts of San Miguel, San José de Chimbo and Guaranda, in which 75% of the population of the province of Bolívar, Ecuador lives, was studied. The inclusion criterion used was adults who had an obvious interest after explaining to them their objectives in co-operating with the project, which was carried out by the Universidad Estatal de Bolívar [State University of Bolívar] with the participation of students from the degree in Social Communication, Nursing and Administration in Disasters and Risk Management, as part of their action in the link with society. Partial results of the project are presented, for which a sample of 1586 surveys obtained in the initial stage of the study were worked with.

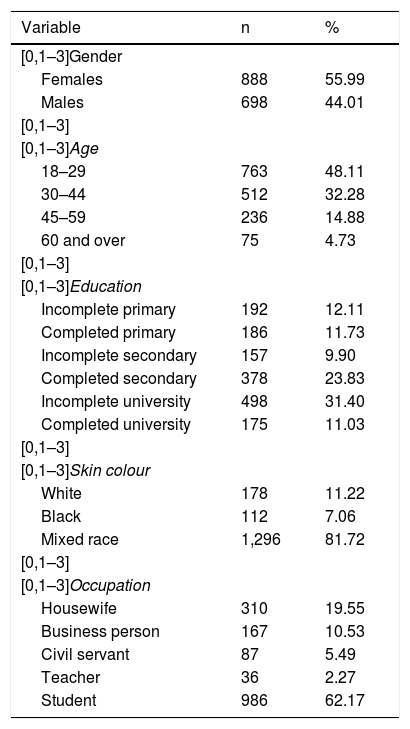

The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Of the participants, 55.99% were female; 48.11% were aged between 18 and 29; 32.28%, were aged between 30 and 44; 14.88% were aged between 45 and 59 and 4.73% were aged 60 and over. An incomplete university education level predominates (31.4%), followed by completed secondary education (23.83%). A total of 81.72% are mixed race; 11.22% white and 7.06% black. Of the sample, 62.17% are students; 19.55%, housewives; 10.51%, business people; 5.49% civil servants and 2.27%, teachers.

Socio-demographic data of the participants.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| [0,1–3]Gender | ||

| Females | 888 | 55.99 |

| Males | 698 | 44.01 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Age | ||

| 18–29 | 763 | 48.11 |

| 30–44 | 512 | 32.28 |

| 45–59 | 236 | 14.88 |

| 60 and over | 75 | 4.73 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Education | ||

| Incomplete primary | 192 | 12.11 |

| Completed primary | 186 | 11.73 |

| Incomplete secondary | 157 | 9.90 |

| Completed secondary | 378 | 23.83 |

| Incomplete university | 498 | 31.40 |

| Completed university | 175 | 11.03 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Skin colour | ||

| White | 178 | 11.22 |

| Black | 112 | 7.06 |

| Mixed race | 1,296 | 81.72 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Occupation | ||

| Housewife | 310 | 19.55 |

| Business person | 167 | 10.53 |

| Civil servant | 87 | 5.49 |

| Teacher | 36 | 2.27 |

| Student | 986 | 62.17 |

Source: field data from the research team, 2017.

After the individual acceptance to collaborate in the study, the survey made up of 25 questions was handed over. The questions were structured in the following way: nine respond to the vision and concepts of the behaviour of adults in actions which involve abuse of members of their family; three investigate respect for the vision of the behaviour in education received from his/her parents; seven analyse the relationship with his/her partner, and six on the behaviour of his/her children, his/her action with them in education and the presence of them in situations of domestic violence.

From the data obtained primarily, a digital database was created, information which was summarised after debugging it.

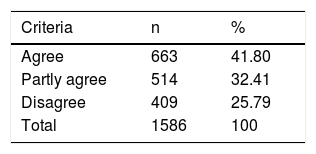

ResultsTable 2 shows the results to the question "discipline at home is achieved with punishment". A total of 42% said that they agree; 32% partly agreed and 26% did not agree.

The responses "agree" and "partly agree" to the question "It is often necessary to shout at children to make them obey" were very similar (37.07 and 36.19%, respectively), while 26.73% said that they disagreed.

To the query regarding whether "victims of abuse are sometimes looking for it, they do things to provoke it", 42.75% said that they disagreed, 29.38% partly agreed and 27.87% agreed.

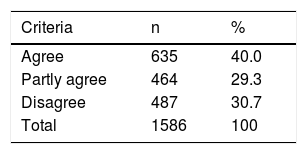

To the statement "emotional abuse is not as serious as physical abuse", 40% of the respondents considered that to be true, with which they underestimate the psychological consequences for those who suffer from it, which is in contrast to the 31% who said that they disagree and the 29% who partly agreed (Table 3).

In the item "I think that the punishments and scoldings of my parents… "Taught me to be better", 69% gave an affirmative response, and for "They caused me pain, sadness", 18% gave an affirmative response. Only 8% considered that "They made me rebel"; 4% that "They were hateful", and 2% that "They served no useful purpose".

To the query, "In my current partner relationship, I have had problems which have ended in blows, pushing and shoving or blows with objects", the statement that the following "never" occur: blows (62%), pushing and shoving (44%) and blows and pushing and shoving (81%) stands out. It is verified that blows "rarely" occur (21%) and 32% for the same category with regard to pushing and shoving as part of arguments with a partner, while 12% affirmed having "blows with objects".

A total of 26% verified that "there are blows, we have both dealt them"; 19% said that "I have received them" and 11% said that "I have dealt them". 44% affirmed that "we have never hit each other".

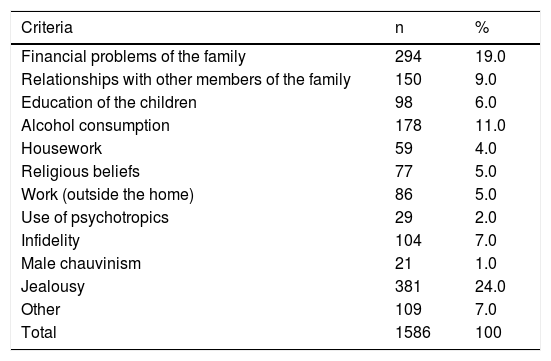

In "The main reason that makes my partner and I argue is…" (Table 4), the following criteria were considered: financial problems of the family, relationships with other members of the family, education of the children, alcohol consumption, household chores, religious beliefs, work (outside the house), use of psychotropics, infidelity, male chauvinism, jealousy and others. The highest percentage corresponds to the cause of jealousy resulting in arguments (24%), followed by financial problems of the family (19%) and alcohol consumption (11%). The following were identified as minor criteria of differences which cause arguments: education of the children (6%), religious beliefs and work outside the house (5% each) and housework (4%).

The main reason that makes my partner and I argue is:

| Criteria | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Financial problems of the family | 294 | 19.0 |

| Relationships with other members of the family | 150 | 9.0 |

| Education of the children | 98 | 6.0 |

| Alcohol consumption | 178 | 11.0 |

| Housework | 59 | 4.0 |

| Religious beliefs | 77 | 5.0 |

| Work (outside the home) | 86 | 5.0 |

| Use of psychotropics | 29 | 2.0 |

| Infidelity | 104 | 7.0 |

| Male chauvinism | 21 | 1.0 |

| Jealousy | 381 | 24.0 |

| Other | 109 | 7.0 |

| Total | 1586 | 100 |

Source: field data from the research team, 2017.

Those who are fathers or mothers of children under the age of 15 were asked some questions with regard to their behaviours.

"I believe that my child misbehaves because…" is evaluated with the criteria: "he/she is very spoilt", "we do not know how to educate him/her", "all children are like that", "he/she is disobedient", "he/she is mischievous", "he/she has problems at school or where they look after him/her", "he/she is irresponsible" and "he/she is unsettled". A total of 35% consider the response "he/she is very spoilt" as the reason for the misbehaviour of children, followed by "all children are like that" (19%). The criteria "we do not know how to educate him/her", "he/she is irresponsible" and "there are problems at home" coincide (11% each). For "in general, when my child misbehaves, I…", the following response options were given: "I scold him/her", "I lose patience and I shout at him/her", "I lose patience and I hit him/her", "I punish him/her in a place", "I punish him/her by not letting him/her watch the television", "I punish him/her until I forget what he/she did", "I punish him/her by not letting him/her go out to play or walk", "I scold or punish him/her", "I fall ill", "I talk to him/her", "I ignore what he/she has done wrong", "I keep quiet". A total of 36% of parents respond that they scold their children, 11% lose patience and hit them, 10% lose patience and shout at them and 11% talk to them.

The following is included in the questionnaire "scolding, punishing or hitting my child causes me… ", for which the possible responses considered were: "pain or bravery", "sadness or a desire to cry", "feeling of guilt" and "satisfaction with the job done". A total of 42% of the parents surveyed affirmed that they feel sad or want to cry, followed by 33% with a feeling of guilt, 14% with pain or bravery and 11% with satisfaction with the job done.

For the appreciation of respect in the family through "My child respects: father, mother, grandparents, sibling", 44% of parents stated that the image of the father is that of the greatest respect for the children; for 27%, it is the maternal figure; for 19% the grandparents and for 9% one of the siblings.

To "My child has witnessed family fights", 35% stated that it had happened occasionally, 25% rarely, 19% many times and 21% said that they had never witnessed family fights.

In "when my child has witnessed family fights he/she has reacted, in general…", the affirmative responses concerning the children being scared or expressing fear (29%), trying to stop the argument (19%) and becoming sad or crying (16%) stand out.

DiscussionThe respondents agree that punishment is part of the discipline in the education of minors, the need to shout at children and that psychological abuse is underestimated compared to physical abuse. The opinion of Urra18 is in contrast to these aspects. He manifests the need to maintain ethics in the education of children, respect them, the explanation for good behaviour and the control of impulses of adults for the activities and actions that they may have. The authors agree with López19 when she states that parents are the first teachers of children. They are their guides in good and bad, a process which is developed gradually with love, patience and firmness, for which they must have defined values, habits and attitudes to take into consideration.

Regarding the actions of violence with customary punishments and scoldings in families, an acceptance of these actions is appreciated as advantageous in personal formation, which is in contrast to that proposed by Urra,18 who affirms that coherence should prevail in the education of boys and girls, which should be without any violence whatsoever. What is identified in the surveys coincides with the statements of Piñero20 which are described in the World Report against violence of boys and girls: fathers and mothers routinely maintain physical punishments or others on their children in the family space.

The results with regard to abuse in partners correspond in a similar way with the studies carried out by Guerri-Pons,21 who states that this event occurs in 30–40% of families and females are the most affected in similar events, although males are not exempt from also suffering from abuse. It is worth highlighting the ramifications on children when they are a silent witness of situations of violence between partners, the psycho-emotional consequences that are engraved in them and transform them into potential aggressors, which Sierra aptly affirms.22

With regards related studies on whether to punish and/or hit girls and boys for misbehaviour, the result is similar to what has been verified in the UNICEF survey in Europe and Central Asia; Piñero20 states that more than 75% of children consider that being hit would not resolve the situations families are facing. The authors propose reflecting on the application of violence on children due to the impact that it has on them, events that lead to feelings of loneliness, sadness and abandonment, due to damaging the emotional bonds between parents and children and due to the possible implications for their integration into life in society.

In relation to the consequences for children of the manifestations of domestic violence, in her study Zarza23 identifies that psychological conditions are predominant and more severe than physical actions in most children who live in families with domestic violence. León24 affirms that "violence against women has a significant effect on childhood morbidity, particularly in the prevalence of episodes of diarrhoea and symptoms of acute respiratory diseases, as well as the boy or girl suffering from physical or psychological violence".

ConclusionsIt is noted that the image of the father holds the greatest respect for children in families from the Bolívar region; punishments, scoldings and/or blows to children are applied in nearly 50% of them. Shouting is the predominant form of arguments between partners; of blows being exchanged, being dealt by both, and the financial factor, jealousy and alcohol consumption being the most common causes of family disputes. In children who witness these forms of behaviour, a feeling of fear or panic predominates. There is an influence of sadness and guilt in parents after scolding, punishing or hitting a child.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Camacho MRM, Valle GMAd, González MIG, Chacán PJC, Aguiar FdRN, Nájera LMG, et al. Violencia intrafamiliar y su repercusión en menores de la provincia de Bolívar, Ecuador. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:23–28.

Work presented at the IV International Congress of Sciences, Technology, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Universidad Estatal de Bolívar [Bolívar State University], Guaranda, Ecuador, held from 5 to 7 July 2017. Available at: http://www.ueb.edu.ec/sitio/images/PDF/INVESTIGACION/2017-congreso/CONGRESO_UEB_2017_3.pdf.