Bipolar disorder (BD) and schizophrenia are included in the group of severe mental illness and are main causes of disability and morbidity in the local population due to the bio-psycho-social implications in patients. In the last 20 years or so, adjunctive psychological interventions been studied with the purpose of decreasing recurrences, stabilising the course of the disease, and improving the functionality in these patients.

ObjectiveTo analyse the psychological effect of a multimodal intervention (MI) vs a traditional intervention (TI) programme in BD I and schizophrenic patients.

MethodsA prospective, longitudinal, therapeutic-comparative study was conducted with 302 patients (104 schizophrenic and 198 bipolar patients) who were randomly assigned to the MI or TI groups of a multimodal intervention programme PRISMA. The MI group received care from psychiatry, general medicine, neuropsychology, family therapy, and occupational therapy. The TI group received care from psychiatry and general medicine. The Hamilton and Young scales, and the Scales for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) and Postive Symptoms (SAPS) were used on bipolar and schizophrenic patients, respectively. The scales AQ-12, TEMPS-A, FAST, Zuckerman sensation seeking scale, BIS-11, SAI-E and EEAG were applied to measure the psychological variables. The scales were performed before and after the interventions. The psychotherapy used in this study was cognitive behavioural therapy.

ResultsThere were statistically significant differences in socio-demographic and clinical variables in the schizophrenia and bipolar disorder group. There were no statistically significant differences in the psychological scales after conducting a multivariate analysis between the intervention groups and for both times (initial and final).

ConclusionThis study did not show any changes in variables of psychological functioning variables between bipolar and schizophrenic groups, who were subjected to TI vs MI (who received cognitive behavioural therapy). Further studies are needed with other psychological interventions or other psychometric scales.

El Trastorno Afectivo Bipolar (TAB) y la Esquizofrenia están incluidos dentro de las enfermedades mentales severas y hacen parte de las primeras causas de discapacidad y morbilidad en la población local debido al compromiso biopsicosocial en los pacientes. En las últimas décadas se han estudiado intervenciones psicológicas adjuntas con el fin de prevenir recurrencias, estabilizar el curso de la enfermedad o mejorar la funcionalidad de los pacientes con dichas patologías.

ObjetivoAnalizar el efecto psicológico de un programa de intervención multimodal (IM) vs la intervención tradicional en sujetos con TAB I y esquizofrenia.

MetodologíaSe realizó un estudio prospectivo, longitudinal, terapéutico-comparativo, con una muestra de 302 pacientes (104 pacientes con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia y 198 pacientes con TAB) que fueron asignados aleatoriamente a un grupo de IM o IT dentro de un Programa de Salud Mental con énfasis en reducción de la carga, el daño y el gasto social de la enfermedad mental PRISMA. Los pacientes asignados a la IM recibían atención por psiquiatría, medicina general, psicología, neuropsicología, terapia de familia y terapia ocupacional y, los pacientes asignados a IT recibían atención por psiquiatría y medicina general. Las escalas realizadas antes y después de las intervenciones fueron las escalas de Hamilton y Young y, las escalas SANS y SAPS, para pacientes bipolares y esquizofrénicos, respectivamente. Para evaluar las variables psicológicas se aplicaron las escalas AQ-12, TEMPS-A, FAST, Búsqueda de sensaciones de Zuckerman, BIS-11, SAI-E y EEAG. La psicoterapia usada en el componente de psicología fue la terapia cognitivo conductual.

ResultadosSe encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en las variables socio-demográficas y clínicas entre el grupo de pacientes con TAB y esquizofrenia. Luego de hacer un análisis multivariado MANCOVA, no se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en los resultados entre el momento inicial y final en los grupos de pacientes TAB y esquizofrenia en ninguna de las escalas aplicadas.

ConclusiónEl presente estudio no evidenció un cambio a nivel psicológico en los pacientes con TAB y con esquizofrenia que estuvieron bajo IT vs IT (quienes recibieron terapia cognitivo conductual). Futuros estudios aplicando otras psicoterapias adjuntas y usando otras escalas psicométricas podrían ser considerados.

Bipolar disorder (BD) and schizophrenia are two of the major psychiatric disorders and are frequently the main causes of consultations at Emergency and Outpatient departments within our sphere. It was previously thought that patients’ impaired functionality was only linked to acute episodes of affective (mania, hypomania and depression) and psychotic symptoms, and that the main therapeutic objectives were aimed at resolving these crises. In the last few decades, studies have shown that the functionality of these patients is associated with subthreshold and negative symptoms, neurocognitive performance, personality traits and the disease awareness level.1

Taking into account that BD and schizophrenia are highly complex disorders with multiple overlapping bio-psycho-social factors, individual and isolated therapeutic strategies often fall short in the face of patients’ and their families’ needs. These disorders have high recurrence rates, are associated with low treatment adherence, have high comorbidities with anxiety and psychoactive substance abuse disorders and are significantly correlated with suicidal ideation, attempted suicide and hetero-aggression.1

The main treatment objectives are to alleviate acute symptoms, to re-establish psychosocial functioning and to prevent relapses and recurrences. The mainstay of treatment continues to be pharmacotherapy. However, there is a gap in the efficacy and effectiveness of the drug response rates reported,2–6 which suggests the need to develop specific psychological treatments.7

Initially, four psychological interventions demonstrated some efficacy in preventing recurrences, stabilising the course of the disease and improving medium-term functionality (1–2 years). These included cognitive therapy and other cognitive behavioural techniques,8–10 interpersonal and social rhythm therapy,11 family focussed therapy12 and other similar forms of family13 and patient group14 psychoeducation. Results from systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed the benefits of psychological interventions as an adjunct therapy to pharmacotherapy in maintenance treatment for BD relapse prevention.15

With this in mind, a multimodal intervention (MI) programme was designed for patients with bipolar I disorder (BID) and schizophrenia, which included assessment by various specialties, such as psychiatry, general medicine, psychology, neuropsychology and neuropsychological rehabilitation, family therapy and occupational therapy, with a view to comparing the primary outcomes thereof versus the traditional intervention (TI), which includes psychiatry and general medicine assessments, much like those provided by the current health service. The interventions included in multimodal therapy were chosen according to the bio-psycho-social intervention model and were determined based on the needs observed in treating patients with severe mental illness in clinical practice. No comparison was made with individual treatments as the investigators wanted to develop a comprehensive care model that could be reproduced in other cities and regions across the country.

In this manner, each component applied its respective battery of tests at the start and end of the intervention in order to determine any changes between the group that received the MI versus the one that received the TI. This article shows the effects on patients under MI vs TI as regards different psychological variables (impulsiveness, aggression, sensation seeking, level of insight and predominant temperament), as well as their degree of functionality subsequent to the intervention.

Materials and methodsParticipantsA prospective, longitudinal, therapeutic-comparative study was conducted on 302 patients, 104 of which had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and 198 with BID. The patients were randomly assigned to the multimodal intervention (MI) or traditional intervention (TI) groups within a Mental Health Programme focusing on reducing burden, suffering and social spending in mental illness (PRISMA).

After randomising the patients, the MI group consisted of 50 patients with schizophrenia and 100 with BID, while the TI group included 54 patients with schizophrenia and 98 with bipolar I disorder. The sample was the flow of patients during the study.

The sample was selected from a patient population diagnosed with BID or schizophrenia who were attending outpatient psychiatric consultations at the Mood Disorders and Psychosis Clinic of one of the city's university hospitals and other institutions. The recruitment and initial assessment of patients began in 2012; the programme was carried out for approximately 2 years and the final assessment ended in February 2015.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Patients diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia according to the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS), previously validated in Colombia16; (2) Being aged between 18 and 60 years; (3) Having had schooling from the age of 5 to 16 years; (4) Having agreed to participate in the study and signed the informed consent form previously explained by the healthcare professional; and (5) Being in good enough health to undertake the tests applied.

Patients with other neurological or psychiatric comorbidities were excluded, along with those with an intellectual disability, classic autism or a personality disorder. Also excluded were subjects with a history of electroconvulsive therapy in the past 6 months and those who had ever suffered severe head trauma. All patients had to sign the informed consent form in order to participate in the study, once this had been explained and any concerns resolved by the investigator. The study was approved by the institution's Ethics Committee.

InstrumentsPatients were diagnosed with BID and schizophrenia using the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS),16 which is translated into Spanish and validated for Colombia, and according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision17 (DSM-IV-TR).

Moreover, various scales were applied to the bipolar I and schizophrenia patients. Among these, the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)18,19 and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)20,21 both validated in Spanish, were used for patients with BID, and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)22 and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS)22 were applied to subjects with schizophrenia. Both groups were evaluated with the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)23 scale for the past month and at the worst point of the last episode.

The battery used in the Psychology component included the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ-12),24,25 the Temperament Scale (TEMPS-A),26 the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST),27 Zuckerman's Sensation Seeking Scale,28 the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11)29 and the Schedule for the Assessment of Insight – Expanded (SAI-E).30

Each of these is detailed below.

Aggression Questionnaire (AQ-12)The Aggression Questionnaire (AQ)24,25 is a 24-item questionnaire that uses a Likert-type scale which measures physical and verbal aggression, anger and hostility. The Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire (1992)25 is one of the most widely used tools in the analysis of aggressive behaviour in psychology.

Temperament Scale (TEMPS-A)The self-applied Temperament Scale (TEMPS-A) is a questionnaire intended to measure the temperamental variations of the subjects. TEMPS-A is a self-assessment questionnaire that enables the presence of four fundamental affective temperaments to be measured (hyperthymic, depressive, cyclothymic and irritable) and the anxious temperament. The version of the TEMPS-A questionnaire included in the study comprises 110 questions.26

Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST)The Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) is a simple, fast and easy-to-use instrument. It was developed to assess the functional limitations presented by patients with mental illnesses, and in particular those with bipolar disorder. One of the virtues of the FAST is its excellent reliability and, being a 24-item scale, it can be easily integrated into clinical practice and research.27

Zuckerman's Sensation Seeking ScaleOn the Zuckerman's Sensation Seeking Scale (Form V), Sensation Seeking (SS) is defined as a psychobiological disposition characterised by the need for “varied, novel and intense experiences”, and the “willingness to take risks for the sake of such experience“.28

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11)The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) is a questionnaire designed to assess personality and the behavioural construct of impulsiveness, and has been used to correlate this trait with other clinical phenomena. The current version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale comprises 30 items that describe common impulsive or non-impulsive behaviours.29

Schedule for the Assessment of Insight – Expanded (SAI-E)The Schedule for the Assessment of Insight – Expanded (SAI-E) assesses insight in patients with psychotic and affective disorders, has good psychometric properties and has been used on various patient populations with mental disorders.30

Evaluation procedureOnce the inclusion and exclusion criteria had been applied to the population and the sample had been obtained, consultations were organised by group in order to explain the study in detail and obtain the informed consent of whomsoever voluntarily agreed to participate in the project. The patients were then coded and, once randomised, an appointment was made for the initial assessment by different healthcare professionals according to the intervention assigned.

InterventionMultimodal interventionThe multimodal intervention included professionals from various healthcare areas who performed regular individual outpatient assessments (between 12 and 18 sessions) based on each patient's needs according to the findings of the initial study assessment. The interventions offered were undertaken by General Medicine, Psychiatry, Psychology, Neuropsychology, Family Therapy and Occupational Therapy. Moreover, patients and their families were offered 10 psychoeducation sessions, which were carried out on a weekly basis. Patients under the multimodal intervention had to complete at least 12 individual outpatient sessions and 10 psychoeducation sessions.

The objective of the General Medicine assessments was to assess the overall health of each patient, to identify and carry out the approach to and initial management of other non-mental illnesses and medical comorbidities, the detection of cardiovascular risk factors and the promotion of healthy lifestyles. Psychiatry assessments were focussed on assessing and monitoring the patients current clinical condition, applying clinical scales and adjusting the pharmacological treatment if necessary.

Psychology assessments sought to tackle any difficulties detected in the initial assessment through a strategy based on cognitive behavioural therapy according to the individual needs of each patient, in order to improve the dysfunctional environment detected. Moreover, assessments were offered by Neuropsychology with the aim of carrying out a neuropsychological rehabilitation plan according to each patient's characteristics and needs, which was complemented with the Functional Remediation Programme strategies of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (Spain) Research Group.31

As well as this, assessments were performed by Occupational Therapy in order to strengthen the patient's overall functionality in their different environments (social, familial and work) and thus establish a therapeutic strategy for socio-occupational rehabilitation. Psychoeducation sessions were performed in groups, involving both patients and relatives, in which general concepts of the disease were discussed, along with crisis trigger factors and their management, recognising warning signs, pharmacological treatment, adverse effects and healthy lifestyles, among others. The psychoeducation groups were coordinated by an Occupational Therapy professional with experience in group psychotherapy.

Traditional interventionThe traditional intervention included 1–2 assessments by General Medicine and Psychiatry only. As such, the patients attended these assessments during the follow-up period with the aim of achieving a level of care similar to that currently offered by the health service. The objectives of the General Medicine and Psychiatry assessments in both interventions (multimodal and traditional) were similar. It is important to highlight that neither patients nor relatives received psychoeducation under the traditional intervention. Under the traditional intervention, the same pharmacological management criteria were followed as in the multimodal intervention, although it could not be guaranteed that the patient was not receiving any other interventions outside of the programme.

Statistical analysisFor the description of the quantitative socio-demographic and clinical variables, measures of central tendency (arithmetic mean), position (median) and dispersion (standard deviation and interquartile range) were used. In the qualitative variables report, absolute frequencies and proportions were used. In the qualitative variables, normal distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and independence (with respect to groups and subgroups) was measured by the chi-squared test and the log-likelihood ratio statistic.

For analysing the scales (Bryant & Smith Aggression Questionnaire, Temperament Scales, Zuckerman's Sensation Seeking Scale, FAST Scale and Barratt Impulsiveness Scale), the Box's test for equal covariances was used. The p value was also determined for each scale (homogeneity of covariance matrices) and, assuming a normal distribution, a multivariate MANCOVA model was adapted, where the dependent variables were the Physical, Verbal, Anger and Hostility subscales for the Bryant & Smith scale, the Depressive, Cyclothymic, Hyperthymic, Irritable and Anxious subscales for the temperament scales, the Emotions, Arousal, Disinhibition and Susceptibility to Boredom subscales for the Zuckerman scale, and the Cognitive, Motor and Non-planning subscales for the Barratt scale.

The variables that were adapted for the analysis were socio-demographic and clinical: gender, major depression with psychosis, alcohol abuse, substance/drug abuse, attempted suicide, age, number of psychiatric hospitalisations, Young scale, Hamilton scale, GAF at the worst point in the last episode and GAF in the past month.

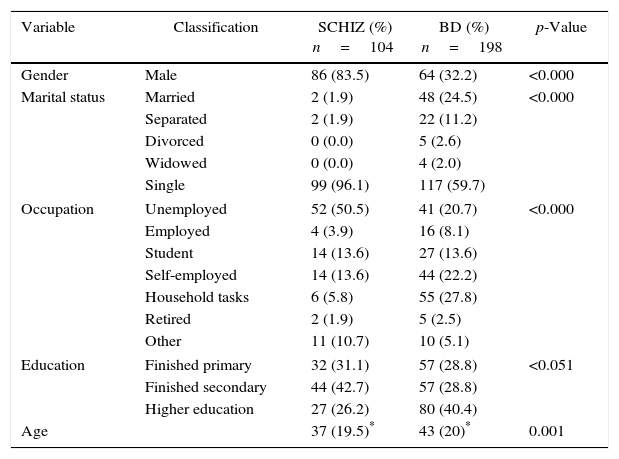

ResultsSocio-demographic characteristics of the patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia in the PRISMA programmeAfter evaluating the socio-demographic variables of patients with BD and schizophrenia in the PRISMA programme, 83% of the schizophrenia patients were found to be male, while 67.8% of the BD patients were female, with a mean age of 37 and 43 years, respectively. On evaluating marital status, occupation and educational level, 96% of the patients with schizophrenia were found to be single, 50% unemployed and only 26% reported having higher education (technical, technological or for a profession). In contrast, 59% of the patients with BD were single, 20% unemployed and 40% had completed higher education. There were statistically significant differences in all four demographic variables (age, gender, marital status, occupation and education) (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of the patients with BD and schizophrenia in the PRISMA programme.

| Variable | Classification | SCHIZ (%) n=104 | BD (%) n=198 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 86 (83.5) | 64 (32.2) | <0.000 |

| Marital status | Married | 2 (1.9) | 48 (24.5) | <0.000 |

| Separated | 2 (1.9) | 22 (11.2) | ||

| Divorced | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.6) | ||

| Widowed | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.0) | ||

| Single | 99 (96.1) | 117 (59.7) | ||

| Occupation | Unemployed | 52 (50.5) | 41 (20.7) | <0.000 |

| Employed | 4 (3.9) | 16 (8.1) | ||

| Student | 14 (13.6) | 27 (13.6) | ||

| Self-employed | 14 (13.6) | 44 (22.2) | ||

| Household tasks | 6 (5.8) | 55 (27.8) | ||

| Retired | 2 (1.9) | 5 (2.5) | ||

| Other | 11 (10.7) | 10 (5.1) | ||

| Education | Finished primary | 32 (31.1) | 57 (28.8) | <0.051 |

| Finished secondary | 44 (42.7) | 57 (28.8) | ||

| Higher education | 27 (26.2) | 80 (40.4) | ||

| Age | 37 (19.5)* | 43 (20)* | 0.001 | |

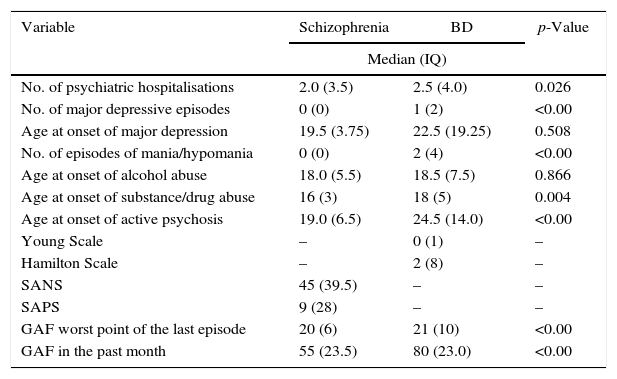

The group of patients with schizophrenia reported an average of 2 hospitalisations over the course of their lives, 15% had a history of alcohol abuse and 31% a history of psychoactive substance abuse, with a mean age at onset of alcohol consumption of 18 years, and 16 years at the onset of psychoactive substance abuse. The average SANS and SAPS scores were 45 and 9 respectively, with a GAF score in the previous month of 55. In the BD patient group, the mean number of hospitalisations was 2.5, with an average of 2 episodes of mania/hypomania and a mean score on the GAF scale of 80 in the previous month; 29% had a history of suicide attempts and 26% a history of alcohol/substance/drug abuse.

Statistical differences between the two groups (schizophrenia and BD) were found in the number of hospitalisations (p=0.026), the age of onset of psychoactive substance abuse (p=0.004) and in the score on the GAF scale in the past month (p=0.001).

There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in the following variables: alcohol abuse (p=0.602); psychoactive substance abuse (p=0.455); history of attempted suicide (p=0.204); and age of onset of alcohol abuse (p=0.86) (Table 2).

Differences in the clinical variables of patients with BD and schizophrenia in the PRISMA programme.

| Variable | Schizophrenia | BD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQ) | |||

| No. of psychiatric hospitalisations | 2.0 (3.5) | 2.5 (4.0) | 0.026 |

| No. of major depressive episodes | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | <0.00 |

| Age at onset of major depression | 19.5 (3.75) | 22.5 (19.25) | 0.508 |

| No. of episodes of mania/hypomania | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | <0.00 |

| Age at onset of alcohol abuse | 18.0 (5.5) | 18.5 (7.5) | 0.866 |

| Age at onset of substance/drug abuse | 16 (3) | 18 (5) | 0.004 |

| Age at onset of active psychosis | 19.0 (6.5) | 24.5 (14.0) | <0.00 |

| Young Scale | – | 0 (1) | – |

| Hamilton Scale | – | 2 (8) | – |

| SANS | 45 (39.5) | – | – |

| SAPS | 9 (28) | – | – |

| GAF worst point of the last episode | 20 (6) | 21 (10) | <0.00 |

| GAF in the past month | 55 (23.5) | 80 (23.0) | <0.00 |

| Variable | Schizophrenia | BD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||

| Alcohol abuse | 16 (15.5) | 37 (18.7) | 0.602 |

| Substance/drug abuse | 32 (31.1) | 52 (26.3) | 0.455 |

| Attempted suicide | 23 (22.3) | 59 (29.9) | 0.204 |

After comparing the demographic (gender, marital status, occupation and educational level) and clinical characteristics of the subgroups of patients with BD and schizophrenia assigned to MI and TI, statistically significant differences were only found in the educational level of the BD group who underwent a MI, where 50% of the patients had some level of higher education compared to 29% of the TI group (p=0.044). There were no statistically significant differences between the subgroups of patients with BD in the Hamilton and Young scale scores or between the subgroups of patients with schizophrenia in the SAPS and SANS scores. Moreover, there were no statistically significant differences in the GAF scale in the past month between the MI and TI subgroups for patients with BD and schizophrenia.

Comparison of scales between the start and end time in patients with BDAfter performing a comparative analysis of the psychology scales between the start and end times on the group with BID who received the MI versus the BID group who received the TI, a statistically significant improvement was identified in the verbal aggression (p=0.04) and hostility (p=0.00) subscales of the Aggression Questionnaire. Moreover, the total score of the Aggression Questionnaire also presented statistically significant differences (p=0.01) for the group of BID patients who underwent MI.

On the Temperament Scale, statistically significant differences were found for the depressive temperament (p=0.00) and irritable temperament (p=0.01) items. The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale also showed a statistically significant improvement for each of the items assessed, as well as for the total score (p=0.00). Furthermore, the Schedule for the Assessment of Insight – Expanded demonstrated an improvement in the awareness items (p=0.00) and total score (p=0.00). In contrast, the Zuckerman's Sensation Seeking Scale did not present any statistically significant difference for any of its items or the total score.

In the group of BID patients who received the traditional intervention, some statistically significant differences were also found on comparing the start and end times, specifically for the cyclothymic (p=0.04) and irritable temperament (p=0.00) items of the Temperament Scale, as well as for all components and the total score of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (p=0.00).

For both BID subgroups (MI and TI), a statistically significant difference was found on the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) at both time points (p=0.00 for both).

After performing the multivariate analysis (adjusted by gender, age, major depression with psychosis, alcohol abuse, psychoactive substance abuse, attempted suicide, number of psychiatric hospitalisations, Young scale score, Hamilton scale score and Global Assessment of Functioning scale score at the worst point), the aforementioned differences were not preserved. In other words, after performing the final analysis, no statistically significant differences were found in the scales applied by Psychology.

Comparison of scales between the start and end time in patients with schizophreniaAfter performing a comparative analysis of the psychology scales between the start and end times on the group of patients with schizophrenia who received the MI versus the schizophrenia group who received the TI, a statistically significant improvement was identified in the cognitive subscale (p=0.00) and total score (p=0.04) of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale for the schizophrenia group receiving the MI, which was not observed in the traditional intervention group.

For both schizophrenia patient subgroups (MI and TI), a statistically significant difference was found on the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) at both time points (p=0.00 for both). In contrast, the Aggression Questionnaire, Temperament Scale, Zuckerman's Sensation Seeking Scale and Schedule for the Assessment of Insight – Expanded did not reveal any statistically significant differences in any of the subgroups.

After performing the multivariate analysis (adjusted by gender, age, major depression with psychosis, alcohol abuse, psychoactive substance abuse, attempted suicide, number of psychiatric hospitalisations, Young scale score, Hamilton scale score and Global Assessment of Functioning scale score at the worst point), these differences were not preserved.

DiscussionThe results in this article form part of the report on a Mental Health Programme focusing on reducing burden, suffering and social spending in mental illness (PRISMA) for patients with schizophrenia and BD who were randomly assigned to a multimodal (MI) or traditional (TI) intervention. The main objective of this part of the investigation was to determine the effects of each intervention on BID and schizophrenia patients from a psychological perspective, including variables such as impulsiveness, aggression, sensation seeking, level of insight and predominant temperament, as well as their degree of functionality subsequent to the intervention. The groups of patients with BD and schizophrenia assigned to each of the treatment arms (MI and TI) presented similar demographic and clinical characteristics, thus demonstrating adequate randomisation. After comparing the scores of the scales applied to the subgroups of patients with BD or schizophrenia receiving the MI versus the TI, between the start and end times, some statistically significant differences were found for the BD and schizophrenia patient subgroups.

In this sense, for the BID subgroup that received the MI, statistically significant improvements were found with respect to the BD subgroup that received the TI for the Aggression Questionnaire and Schedule for the Assessment of Insight – Expanded. For both subgroups, statistically significant improvements were found on the Temperament Scale, the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) and the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. No statistically significant improvements were detected on a given scale, except for the BD subgroup that received the TI.

As regards the group of patients with schizophrenia, the subgroup that received the MI showed a statistically significant improvement on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale in comparison to the subgroup that received the TI. Both subgroups presented a statistically significant improvement on the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST). Moreover, like the BID group, no statistically significant improvements were detected on a given scale, except for the subgroup that received the TI.

Nevertheless, none of these findings, both for the BID and schizophrenia patient groups, was preserved after performing the multivariate analysis. As such, the MI was not shown to be superior to the TI for treating and approaching the psychological component of patients with BID and schizophrenia following a psychotherapeutic plan based on a 12-month follow-up of cognitive behavioural therapy.

This study demonstrates that the multimodal intervention did not modify the psychological variables of patients diagnosed with BID or schizophrenia in comparison to the traditional intervention. The MI was not shown to be inferior to the TI with respect to the different patient groups’ outcomes.

Despite the existence of adjunct psychotherapies that have been proven to improve outcomes,32 not all studies have had positive results.10,33–36 Even now, it is still unclear as to whether there are some populations that benefit more from certain types of psychotherapy, or the best time to implement these psychological interventions.37 However, among the possible explanations as to why no statistically significant differences were found, the authors propose the following hypotheses:

- •

Changes in the psychological variables of BID and schizophrenia patients generally require more extensive and continuous processes. As such, more frequent and longer-lasting interventions may be needed in order to achieve better therapeutic effects.

- •

The instrument used to measure the effect of the multimodal programme on the patient's psychological dynamics did not capture the variables in which there could have been a change, so other psychometric instruments should be explored in the future.

- •

Despite cognitive behavioural therapy being described as one of the psychological intervention strategies in patients with BD, there is evidence with other strategies such as interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and functional remediation, among others. Moreover, although the intervention was complemented with the Functional Remediation Programme strategies of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (Spain) Research Group, this was modified and adapted to our study and does not preserve all of the proposed properties.

- •

The population of patients included in this study comprised patients diagnosed with BID or schizophrenia, unlike the majority of studies which included patients with bipolar II disorder (BIID).

- •

The study performed predominantly quantitative measurements, so it is possible that a narrative and qualitative approach might have identified significant changes in the psychological component which are difficult to quantify with the tools employed. It is important to emphasise this last hypothesis, because strikingly, many of the patients and relatives who participated in the programme showed a high degree of satisfaction and recognised improvements in their processes. This breakthrough was also recognised by the psychology professional who accompanied and assessed the patients throughout the process.

The authors recognise that the study has limitations, such as the failure to blind patients and assessors, and the presence of interventions that took place alongside the programme which could affect outcomes. Furthermore, the sample corresponds to a population with heterogeneous pharmacotherapy, multiple medical and psychiatric comorbidities, and a high consumption of psychoactive substances, meaning that the patients received some other type of care within the health service that could not be eliminated for ethical reasons. In contrast, among the study's strengths are its sample size, adequate randomisation for each intervention arm, the design of individualised treatment programmes, the management of a very sick population and the use of highly experienced therapists.

ConclusionsThis study showed no changes in the psychological variables of patients with bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia who underwent a multimodal intervention programme that included cognitive behavioural therapy, in comparison to the traditional intervention. BD and schizophrenia are chronic disorders and patients generally present significantly compromised functionality. For this reason, future studies should include a longer psychotherapeutic intervention, with more frequent consultations and using other measurement instruments to thus determine the actual utility of psychosocial interventions on severe mental illnesses, as well as which is the best option, on what population to use it and when to carry it out.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingThis project was funded by Colciencias, CODI – University of Antioquia and the San Vicente University Hospital Foundation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Colciencias, CODI, the University of Antioquia, the San Vicente University Hospital Foundation and PRISMA U.T.

Please cite this article as: Díaz-Zuluaga AM, Vargas C, Duica K, Richard S, Palacio JD, Berruecos YA, et al. Efecto de una intervención multimodal en el perfil psicológico de pacientes con Esquizofrenia y TAB tipo I: Estudio del Programa PRISMA. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2017;46:56–64.