Fibromyalgia is a common cause of chronic pain in the world, with a prevalence of 0.2–6.4% in the general population. These patients are more likely to have neuropsychiatric disorders. The objective of this study was to describe the sociodemographic and clinical profile of patients with fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric comorbidity.

MethodsA cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted in which Information was collected from the medical records of patients with fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric comorbidity, from specialist institution in Antioquia, during the years 2010 to 2016. Descriptive statistics tools were applied.

ResultsOf the 1106 medical records with a confirmed diagnosis of fibromyalgia, 497 had neuropsychiatric comorbidity. The median age was 54 years (IQR 15), and the majority were women, residing in an urban area, and were married or living with their partner. Low-medium socioeconomic status and basic-medium educational level were the most reported. The most frequent symptoms were sleep disturbances (70.6%), myalgia (66.4%), and chronic fatigue (55.9%). The most frequent neuropsychiatric disorders were depression (85.7%), migraine (35%), and anxiety (14.7%). The most commonly used drugs were serotonin and dual reuptake inhibitors, acetaminophen, and GABAergic drugs. A low percentage was managed with complementary therapies and psychological intervention.

ConclusionsFibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric diseases are diseases that frequently coexist. Although the sociodemographic and clinical presentation is as described in the literature, the presence of depression was greater in this population. A multidisciplinary therapeutic approach would favor the quality of life of the patients and the course of the disease.

La fibromialgia es una causa común de dolor crónico en el mundo, con una prevalencia en la población general del 0,2% al 6,4%. Estos pacientes tienen una mayor probabilidad de presentar trastornos neuropsiquiátricos. El objetivo fue describir el perfil sociodemográfico y clínico de pacientes con fibromialgia y comorbilidad neuropsiquiátrica.

MétodosEstudio transversal, descriptivo. Se recolectó información de las historias clínicas de pacientes con fibromialgia y comorbilidad neuropsiquiátrica, de una institución especializada en Antioquia, durante los años 2010 al 2016. Se aplicaron herramientas de estadística descriptiva.

ResultadosDe 1.106 registros médicos con diagnóstico confirmado de fibromialgia, 497 presentaban comorbilidad neuropsiquiátrica. La mediana de edad fue de 54 años (RIC 15), la mayoría eran mujeres, residían en zona urbana y estaban casados o convivían con su pareja. Estatus socioeconómico bajo-medio y nivel educativo básico-medio, fueron los más reportados. Los síntomas más frecuentes fueron alteraciones del sueño (70,6%), mialgias (66,4%) y fatiga crónica (55,9%). Los trastornos neuropsiquiátricos más frecuentes fueron depresión (85,7%), migraña (35%) y ansiedad (14,7%). Los fármacos más utilizados fueron los inhibidores de la recaptación de serotonina y duales, acetaminofén y gabaérgicos. Manejo con terapias complementarias e intervención psicológica se observaron en baja proporción.

ConclusionesLa fibromialgia y las enfermedades neuropsiquiátricas son patologías que coexisten con frecuencia; la presentación sociodemográfica y clínica es similar a lo descrito en la literatura, sin embargo, la presencia de depresión en esta población fue mayor. Un enfoque terapéutico transdisciplinario, favorecería la calidad de vida de los pacientes y el curso de la enfermedad.

Fibromyalgia is a common cause of chronic musculoskeletal pain around the world, with a prevalence among the general population ranging from 0.2% to 6.4%, and a mean rate of 3.1% in America, 2.5% in Europe and 1.7% in Asia.1 Such prevalence varies according to the different set of criteria of the American College of Rheumatology.2 Fibromyalgia reaches its highest peak at around the seventh decade of life3 and is more frequent in females.4 The prevalence reported in Colombia among the adult population was 0.72% (CI: 0.47–1.11%).5

All patients with chronic pain, whether from fibromyalgia or not, have a higher probability of developing psychiatric disorders, particularly depression and anxiety.6–8 A significantly higher prevalence of depressive disorders and anxiety has been reported in patients with fibromyalgia, as compared to controls, in the range of 20–80% and 13–63.8% of the cases, respectively.9 Likewise, cognitive involvement has been described in these patients, associating the level of pain with the level of cognitive dysfunction.10

Most of the information about the epidemiological profile of fibromyalgia has been generally described, with few data about patients who experience this pathology concomitantly with neuropsychiatric disorders. Based on the observations of a primary trial in a population with 1106 patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia, in whom psychiatric conditions were more frequently reported (31.1%), followed by migraine (30.9%),11 the decision was made to conduct a secondary analysis aimed at describing the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients with fibromyalgia and the frequency of psychiatric comorbidities, these patients received care at a specialized institution between 2010 and 2016.

Patients and methodsThis was a retrospective, descriptive, cross-section trial, based on the medical records of patients over 18 years old, referred from primary care institutions to a specialized medical neurological center that delivers services to patients from any region in Colombia, who are affiliated to the General Social Security System (Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud – SGSSS), in whichever regimen modality and voluntary membership health plans, between 2010 and 2016. Since fibromyalgia is classified under the International Classification of Diseases (CIE-10), the medical records were screened according to the codes associated with pain, acute pain, chronic pain, intractable pain, persistent pain, myalgias or neuromuscular disorders. In total, there were 6154 medical records that met the criteria under the ICD 10 codes provided; a second selection was performed by the project investigators, excluding any records of patients under 18 years old and unrelated pathologies such as congenital neuromuscular diseases; hence, the final total number of records was 5344. The review of the medical records and subsequent collection of data was conducted by 5 students that had been previously educated and trained in the electronic medical record system of the institution, and the processes of capturing variables were standardized. Furthermore, as a strategy to control any information biases, a complete verification of the database was conducted by one of the investigators. A total of 1106 medical records were collected, with a confirmed diagnosis of fibromyalgia by specialized physicians and pursuant to the criteria of the American Association of Rheumatology.

The sociodemographic and clinical variables were collected from the 1106 medical records, including any neuropsychiatric comorbidities existing in this population, which should have been documented as part of their personal history, prior or the time of diagnosis during the medical visit, according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM IV). Patients who did not have a confirmed diagnosis by the specialists were excluded. 497 medical records that complied with the diagnoses of fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric comorbidity were obtained, and were subject to a secondary analysis. One hundred percent of the medical records of patients with a neuropsychiatric background were reviewed during the process, confirming first of all, that the diagnosis had been made by a specialized medical practitioner, and secondly, that the diagnosis was confirmed.

The SPSS 23 software, licensed to the Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia, was used in the analyses, including observations about frequencies, normal distribution analysis using the Kolmogorov Smirnov test, central tendency and dispersion measures according to age.

This study was approved by the Ethics in Research Committee of the Instituto Neurológico de Colombia.

ResultsFrom 2010 through 2016, the Instituto Neurológico de Colombia, delivered care to 497 patients with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric comorbidity.

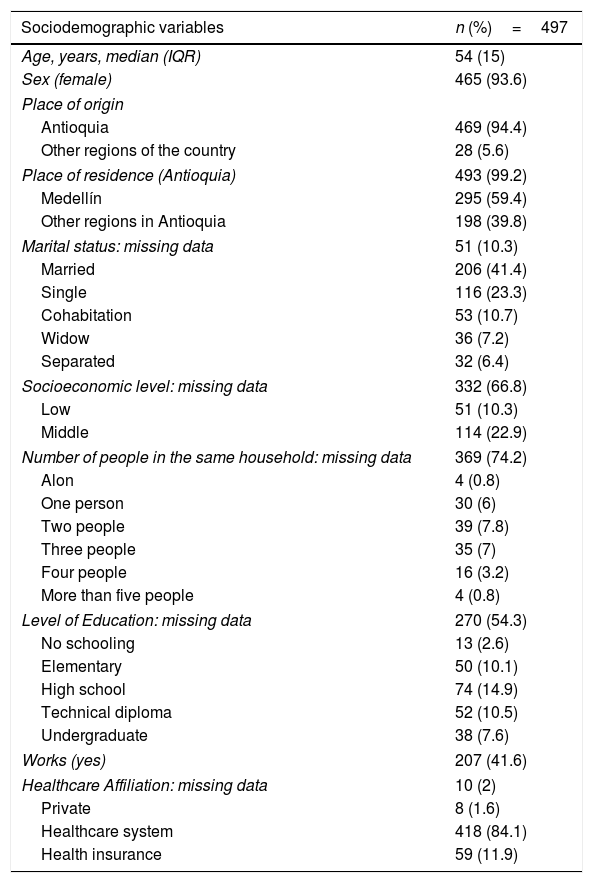

The most frequently identified characteristics were: being in their 60's, being a female, resident of Antioquia (Colombia), married or living with a partner, middle to low socioeconomic status, basic to middle level of education (high school and technical degree) and being responsible for 2–3 people. 41.6% of the patients were working at the time they received care, and 97.4% were affiliated to the social security system SGSSS, regardless of the modality (affiliate member, subsidized, tax-payer and special regimen) (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric comorbidity.

| Sociodemographic variables | n (%)=497 |

|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 54 (15) |

| Sex (female) | 465 (93.6) |

| Place of origin | |

| Antioquia | 469 (94.4) |

| Other regions of the country | 28 (5.6) |

| Place of residence (Antioquia) | 493 (99.2) |

| Medellín | 295 (59.4) |

| Other regions in Antioquia | 198 (39.8) |

| Marital status: missing data | 51 (10.3) |

| Married | 206 (41.4) |

| Single | 116 (23.3) |

| Cohabitation | 53 (10.7) |

| Widow | 36 (7.2) |

| Separated | 32 (6.4) |

| Socioeconomic level: missing data | 332 (66.8) |

| Low | 51 (10.3) |

| Middle | 114 (22.9) |

| Number of people in the same household: missing data | 369 (74.2) |

| Alon | 4 (0.8) |

| One person | 30 (6) |

| Two people | 39 (7.8) |

| Three people | 35 (7) |

| Four people | 16 (3.2) |

| More than five people | 4 (0.8) |

| Level of Education: missing data | 270 (54.3) |

| No schooling | 13 (2.6) |

| Elementary | 50 (10.1) |

| High school | 74 (14.9) |

| Technical diploma | 52 (10.5) |

| Undergraduate | 38 (7.6) |

| Works (yes) | 207 (41.6) |

| Healthcare Affiliation: missing data | 10 (2) |

| Private | 8 (1.6) |

| Healthcare system | 418 (84.1) |

| Health insurance | 59 (11.9) |

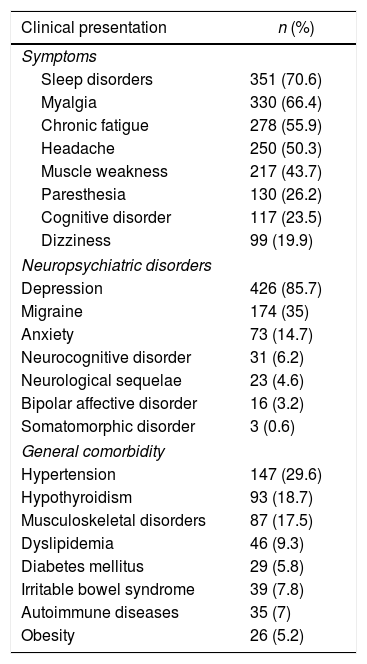

The most frequent psychosomatic symptoms of patients with fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric comorbidity – more than 50% – were sleep disorders, followed by myalgias, chronic fatigue and head ache (Table 2).

Symptoms and comorbidities associated to patients with fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric disease.

| Clinical presentation | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Sleep disorders | 351 (70.6) |

| Myalgia | 330 (66.4) |

| Chronic fatigue | 278 (55.9) |

| Headache | 250 (50.3) |

| Muscle weakness | 217 (43.7) |

| Paresthesia | 130 (26.2) |

| Cognitive disorder | 117 (23.5) |

| Dizziness | 99 (19.9) |

| Neuropsychiatric disorders | |

| Depression | 426 (85.7) |

| Migraine | 174 (35) |

| Anxiety | 73 (14.7) |

| Neurocognitive disorder | 31 (6.2) |

| Neurological sequelae | 23 (4.6) |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 16 (3.2) |

| Somatomorphic disorder | 3 (0.6) |

| General comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 147 (29.6) |

| Hypothyroidism | 93 (18.7) |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 87 (17.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 46 (9.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 29 (5.8) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 39 (7.8) |

| Autoimmune diseases | 35 (7) |

| Obesity | 26 (5.2) |

Some of the most frequent neuropsychiatric comorbidities included depression, migraine, and anxiety; mixed anxiety and depression disorder was present in 11.47% (57 patients); the rest of the neuropsychiatric conditions were only reported in less than 10% of the cases. Hypertension was the most frequent general comorbidity reported (Table 2).

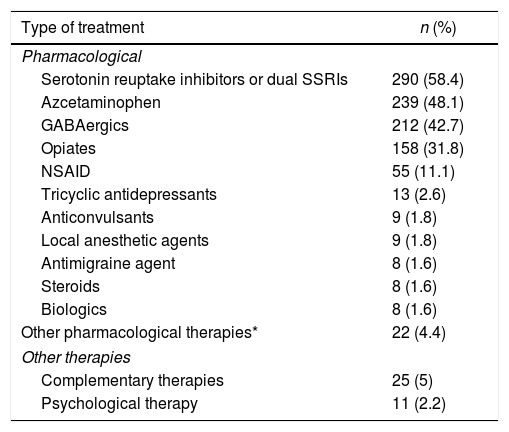

93.6% of the patients with fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric comorbidity received pharmacological therapy, and the most frequently used drugs were the serotonin reuptake inhibitors or dual SSRIs and acetaminophen. The use of other World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledged complementary therapies, such as: acupuncture, meditation, yoga, Taiichi, inter alia, were reported in 5% of the patients. Only 2.2% of the patients with fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric comorbidities received psychological treatment (Table 3).

Types of treatments administered to patients with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric disease.

| Type of treatment | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Pharmacological | |

| Serotonin reuptake inhibitors or dual SSRIs | 290 (58.4) |

| Azcetaminophen | 239 (48.1) |

| GABAergics | 212 (42.7) |

| Opiates | 158 (31.8) |

| NSAID | 55 (11.1) |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 13 (2.6) |

| Anticonvulsants | 9 (1.8) |

| Local anesthetic agents | 9 (1.8) |

| Antimigraine agent | 8 (1.6) |

| Steroids | 8 (1.6) |

| Biologics | 8 (1.6) |

| Other pharmacological therapies* | 22 (4.4) |

| Other therapies | |

| Complementary therapies | 25 (5) |

| Psychological therapy | 11 (2.2) |

This study focused on a population with a concomitant diagnosis of fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric diseases, based on the observed high frequency of coexistence of these two conditions in the primary study11; hence, a secondary analysis was conducted, with a view to describing its sociodemographic and clinical profile.

Similar to the literature, this population exhibited an older age of presentation and a higher frequency among females.6,12–14 The prevalence in the female adult population studies ranges from 2.4% to 6.8%,15,16 with a 3:1 female to male ratio.1

More than one half of the patients in this study were married or lived with a partner, which is a similar finding to that reported by Castelli et al.,13 in which most of the population was married. In contrast, Hadlandsmyth et al.,17 reported that 53% of the population were single, divorced or widowed. With regards to marital status, there is no consensus in the literature; there are some trials in which fibromyalgia was more frequent among widows,15 while others reported a higher frequency among married patients,18 and White et al.19 said that there was a higher frequency among the divorced population.

In terms of the level of education, most patients had basic and middle education, similar to what Castelli et al.13 reported, while in the study by Hadlandsmyth et al.,17 63% most patients had a bachelors or university degree. Other trials have reported higher frequencies of the disease among patients with lower levels of education.15,19–22 Overall, the findings with respect to these two sociodemographic variables are not constant, and this may be due to the typical characteristics of each population group in which the various trials were conducted.

In terms of the socioeconomic status, most patients were in a middle to low level. According to the literature, the lower the family income, the higher the prevalence of fibromyalgia.15,18,19,22,23 Similarly, it has been found that generalized chronic pain is more common among the poorest. This relationship has been partially explained by other factors such as phycological distress, poor mental health, and adverse life events.24 Based on the literature, a relationship between fibromyalgia and low income has been described, reporting more severe symptoms and functional decline, whilst the level of pain, depression, and anxiety remained constant. Although fibromyalgia affects all socioeconomic groups, the social factors, in addition to the specific characteristics of the disease or the mental status, seem to play a significant role in the way patients perceive the disease.25

Some of the major symptoms reported by patients include sleep disorders and chronic fatigue. The literature reportes that most patients with fibromyalgia experience sleep disorders, and more serious sleep disruptions lead to increased severity of the disease.26,27 Restless sleep has been reported with a frequency of 70–80% of the patients with fibromyalgia.28 Although there are no studies to identify the proportion of this symptom in patients with neuropsychiatric comorbidity and fibromyalgia, the findings by Mork and Nilsen29 in their prospective trial with 12,350 women without fibromyalgia should be highlighted. This authors claim that the presence of this symptom is a risk factor for the development of fibromyalgia, regardless of age, weekly physical exercise, body mass index, emotional symptoms, cigarette smoking, or level of education. It has also been said that fibromyalgia may result in sleep disorders mediated by the different mechanisms involved in pain sensitivity which are altered in these individuals.30 In the trial conducted by Faro et al.31 they reported the presence of fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue in 54%, in addition to the fact that the levels of fatigue and pain were higher in these patients.

The presence of depression in patients with fibromyalgia was the most frequent comorbidity identified in this trial; these data are similar to those described by other authors, where this psychopathology was reported in around 20–80% of the cases.9,13 Bi-directional associations have been described between depression and fibromyalgia, so that whichever disease develops first, it may increase the risk of subsequently developing the other; this may involve a shared pathophysiology between the two conditions, and could be a potential explanation as to why these two diseases so frequently coexist.12,32–34 With respect to anxiety, the percentage occurrence is consistent with the findings in other trials, reporting a prevalence of around 13–63.8%.9,13 When considering the mental health study conducted in Colombia in 2015, one of the findings was that people with chronic conditions (i.e. fibromyalgia) and older, have a higher prevalence of experiencing mental disorders; moreover, this study also found that in patients over 45 years old, fibromyalgia was the third pathology in importance among this population.35,36

Headache and migraine were frequently present in these patients. In the literature, the association between fibromyalgia and headache is significant, in addition to episodic migraine, chronic migraine, and tension headache.1 In the article by Onder et al.37 they reported this comorbidity in 30.3% of the cases, whilst the study by Marcus et al.38 reported 24.3%. Whealy et al.39 said that the patients with fibromyalgia and migraine comorbidity report more depressive symptoms (OR 1.08, p<0.0001), higher headache intensity (OR 1.149, p=0.007), and are more prone to experience severe migraine-associated disability (OR 1.23, p=0.004) as compared against the controls with no fibromyalgia.

In terms of the treatment approach for this population, it is surprising to see the very low percentage of patients receiving non-pharmacological therapies, mainly psychological treatment. Keeping this observation in mind and the recommendations in the literature about the multimodal approach to this pathology,40,41 this finding needs to be emphasized, particularly considering that the majority of the people assessed in this study are affiliated to the social security system or have private insurance, which cover psychological interventions and some complementary therapies. This fact leads to the hypothesis that it is not an economic factor that is responsible for this finding, but rather, as suggested by Campo-Arias et al.,42 there is a stigmatization of mental disease in the minds of the practitioners, of patients, and of the society as a whole. So, this becomes a barrier to accessing mental health services and is a limiting factor to a more transdisciplinary approach to this population.

Additionally, we must keep in mind that the SGSSS in Colombia faces some challenges with regards to access to medical services, since although insurance coverage has expanded, access to healthcare has declined significantly, based on the National Quality of Life Survey.43

It is imperative that these patients be approached from primary care, supported by the mental health care services available in the system,44 with a view to lower the impact on quality of life, social and family environment, personal, labor and healthcare costs.45

Since this is a retrospective study, this represents a significant limitation in terms of the certainty of the diagnosis of the neuropsychiatric disease in this population. However, control strategies were implemented in an attempt to reduce this bias. Another limitation was the percentage of missing data for some variables, such as socioeconomic status and the level of education, due to under-registration of this information in the medical records. It should be highlighted that there are few studies in patients with fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric pathology in Colombia, to be able to compare the epidemiological profile of this population.

The conclusion is then that fibromyalgia and neuropsychiatric diseases are conditions that frequently co-exist in this population and require a transdisciplinary approach, in order to improve the quality of life of patients and the course of their disease. To accomplish this goal, it would be necessary to raise the awareness of patients, caregivers, healthcare staff, and the community as a whole, with regards to the co-existence of these diseases and allow for changes in the treatment approach, combining pharmacological therapy with psychotherapeutic and complementary strategies, based on a sound level of evidence.46–48

FinancingThe Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia funded this study through the Research Fund, Project code INV2042.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

To all the staff members of the institution that made this study possible; to the three students who helped with collecting the data but were unable to continue until the end because of their responsibilities with the mandatory social service program.

Please cite this article as: Henao Pérez M., López Medina D.C., Arboleda Ramírez A., Bedoya Monsalve S., Zea Osorio J.A. Comorbilidad neuropsiquiátrica en pacientes con fibromialgia. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2020;27:88–94.