Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a systemic autoimmune disease in which gastrointestinal manifestations are a frequent complication. Gastrointestinal involvement is present in up to 90 % of patients. The most affected areas are the esophagus and the anorectal tract. Reflux, heartburn and dysmotility are the leading causes of gastrointestinal discomfort. Disordered anorectal function can occur early in the course of SSc and is an important factor in the development of fecal incontinence. Current recommendations to treat gastrointestinal disorders in SSc include the use of proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics and rotating antibiotics. This review discusses the proposed pathophysiological mechanisms, the clinical presentation, the different diagnostic techniques and the current management of the involvement of each section of the gastrointestinal tract in SSc.

Gastrointestinal tract (GIT) involvement is common in patients with Systemic sclerosis (SSc), affecting up to 90 % of patients,1–4 and being an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the disease.5

A dysfunction of the microcirculation, the immune system and the fibrosis control mechanisms is present in the GIT in SSc like other complications of the disease. The esophagus is the most affected GIT area in SSc and dysphagia and gastro-esophageal reflux disease are the main manifestations.6,7 Gastric involvement is less frequent, although it may be responsible for delayed gastric emptying and gastric antral vascular ectasia.8–11 Intestinal involvement, although usually asymptomatic, can be life-threatening. The small intestine can suffer from intestinal stasis and predispose to bacterial overgrowth that causes severe diarrhea, abdominal pain and weight loss. Colonic involvement can cause severe constipation.12,13 The anorectal area can be affected in more than 50 % of patients and cause great impact in quality of life.14 The presence of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) occurs relatively frequently in patients with SSc (7–17 %), especially in limited cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis (lcSSc).15,16

The University of California, Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium Gastrointestinal Tract 2.0 (UCLA GIT 2.0) instrument can be used to assess the presence and severity of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with SSc as well as their impact on the quality of life. It has been validated and the patients themselves report their symptoms, through 34 questions, grouped into 7 subgroups: reflux, bloating, diarrhea, fecal dirt, constipation, emotional well-being and social functioning, scored according to severity.17

There are no specific randomized clinical trials to assess different therapies for the management of complications of GIT in patients with SSc, and most treatment options are based on evidence in other diseases or on expert recommendations.

In this manuscript we review the recent knowledge of the pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, tests and treatments used to manage the different gastrointestinal manifestations in SSc.

MethodsLiterature search methodsA bibliographic research was carried out until June 2019, to find studies that met the criteria for inclusion in the MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Library databases.

When conducting the research in Medline, this was done through Pubmed using the MeSH terms: systemic, orofacial sclerosis, microstomia, xerostomia, periodontal disease, dysmotility, gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophageal dysphagia, Barret esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma, gastroparesis, watermelon stomach, intestinal dysmotility, constipation, diarrhea, intestinal bacterial overgrowth, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, intestinal cystoid pneumatosis, diverticulosis, primary biliary cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, pancreatic insufficiency, fecal incontinence, rectal prolapse.

Only articles published in English language were included.

Article selection and information extractionSelected articles were saved in a database; initially, those articles that had the keywords included in the abstract or in the title were taken into account. Subsequently, those articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were ruled out, and a committee was held among the authors to unify the database and choose those articles that were relevant to this review.

Inclusion criteriaFor the selection of studies, it was taken into account that they met the following inclusion criteria in terms of type of study, population, and intervention.

- •

Type of studies: Meta-analyses, systematic reviews (SR) of randomized clinical trials (RCTs), RCTs, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, and institutional protocols have been considered for inclusion. It has not been used as a criterion that the studies had a minimum follow-up time or a minimum sample size.

- •

Type of population: patients over 18 years old with SSc and gastrointestinal involvement.

- •

Intervention: Studies describing the gastrointestinal condition, explaining the pathophysiology, clinic, diagnostic techniques, prognosis, treatment and complications.

- •

Articles without access to full text

- •

Duplicate articles

- •

Studies that were not conducted in humans

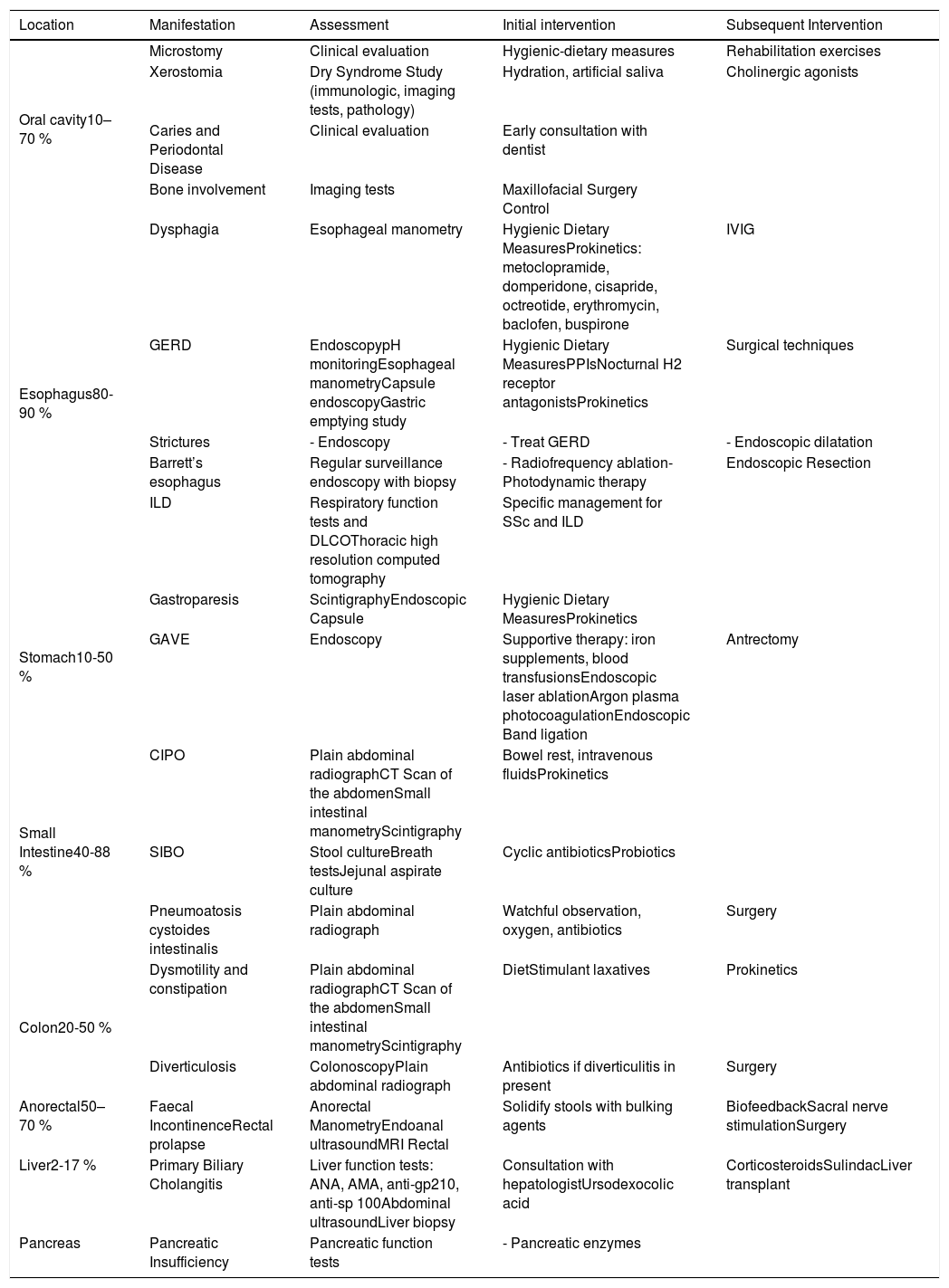

At the end of the research, a total of 2101 articles were analyzed by the researchers. After excluding duplicate articles, articles without access to full text or non-human studies, we obtained a total of 148 articles. Table 1 summarizes GIT complications in SSc and their approach that we found on literature.

Complications of gastrointestinal involvement in SSc.

| Location | Manifestation | Assessment | Initial intervention | Subsequent Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral cavity10–70 % | Microstomy | Clinical evaluation | Hygienic-dietary measures | Rehabilitation exercises |

| Xerostomia | Dry Syndrome Study (immunologic, imaging tests, pathology) | Hydration, artificial saliva | Cholinergic agonists | |

| Caries and Periodontal Disease | Clinical evaluation | Early consultation with dentist | ||

| Bone involvement | Imaging tests | Maxillofacial Surgery Control | ||

| Esophagus80-90 % | Dysphagia | Esophageal manometry | Hygienic Dietary MeasuresProkinetics: metoclopramide, domperidone, cisapride, octreotide, erythromycin, baclofen, buspirone | IVIG |

| GERD | EndoscopypH monitoringEsophageal manometryCapsule endoscopyGastric emptying study | Hygienic Dietary MeasuresPPIsNocturnal H2 receptor antagonistsProkinetics | Surgical techniques | |

| Strictures | - Endoscopy | - Treat GERD | - Endoscopic dilatation | |

| Barrett’s esophagus | Regular surveillance endoscopy with biopsy | - Radiofrequency ablation- Photodynamic therapy | Endoscopic Resection | |

| ILD | Respiratory function tests and DLCOThoracic high resolution computed tomography | Specific management for SSc and ILD | ||

| Stomach10-50 % | Gastroparesis | ScintigraphyEndoscopic Capsule | Hygienic Dietary MeasuresProkinetics | |

| GAVE | Endoscopy | Supportive therapy: iron supplements, blood transfusionsEndoscopic laser ablationArgon plasma photocoagulationEndoscopic Band ligation | Antrectomy | |

| Small Intestine40-88 % | CIPO | Plain abdominal radiographCT Scan of the abdomenSmall intestinal manometryScintigraphy | Bowel rest, intravenous fluidsProkinetics | |

| SIBO | Stool cultureBreath testsJejunal aspirate culture | Cyclic antibioticsProbiotics | ||

| Pneumoatosis cystoides intestinalis | Plain abdominal radiograph | Watchful observation, oxygen, antibiotics | Surgery | |

| Colon20-50 % | Dysmotility and constipation | Plain abdominal radiographCT Scan of the abdomenSmall intestinal manometryScintigraphy | DietStimulant laxatives | Prokinetics |

| Diverticulosis | ColonoscopyPlain abdominal radiograph | Antibiotics if diverticulitis in present | Surgery | |

| Anorectal50–70 % | Faecal IncontinenceRectal prolapse | Anorectal ManometryEndoanal ultrasoundMRI Rectal | Solidify stools with bulking agents | BiofeedbackSacral nerve stimulationSurgery |

| Liver2-17 % | Primary Biliary Cholangitis | Liver function tests: ANA, AMA, anti-gp210, anti-sp 100Abdominal ultrasoundLiver biopsy | Consultation with hepatologistUrsodexocolic acid | CorticosteroidsSulindacLiver transplant |

| Pancreas | Pancreatic Insufficiency | Pancreatic function tests | - Pancreatic enzymes |

SSc=Systemic Sclerosis, IVIG=intravenous immunoglobulins, GERD=Gastroesophageal reflux disease, ILD=interstitial lung disease, DLCO=diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide, GAVE=gastric antral vascular ectasia, CIPO=Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, SIBO=small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, ANA=antinuclear antibody, AMA=antimitochondrial antibodies.

The oral cavity is affected in between 10–70 % of patients with SSc.18 The most common complications are external to the oral cavity such as microstomy and microcheilia, both present in 50–80 % of cases.19–21

Microstomy is mainly caused by fibrosis of the perioral tissues and produces a reduction in oral opening22; Occasionally it can affect speech or chewing and predispose to periodontal diseases.21 When it is observed in early stages, mouth stretching exercises, massages, Kabat technique (exercises on facial muscle stimulation) and kinesitherapy are recommended23 regularly to maintain the beneficial effect.24

Xerostomia occurs in 30–68 % of patients19,20 and overlap disease with Sjögren syndrome can appear in up to 23 % of cases.25 Oral dryness favors tooth decay, taste disturbance, atrophy and mouth infections.21,26 To reduce symptoms, the intake of small amounts of water and the use of artificial saliva mouthwashes are recommended.20,21 In periodontal disease microstomy, the increase in interincisal distance27,28 and a defective oral hygiene are involved. It is recommendable to perform periodic examinations by dentists with experience in SSc.28 Other less frequent complications are mandibular bone involvement or the presence of temporomandibular arthropathy.30 An increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma in the tongue has been found in patients with SSc.31

EsophagusEsophageal involvement is the most frequent GIT affectation, present in up to 90 % of cases,6,7,32,33 that has been described more commonly in lcSSc.4 The pathological mechanisms proposed are: vascular damage with hypoperfusion and ischemia,22 a neurological damage from the microvascular changes of the vasa vasorum and a nervous compromise due to inflammatory and/or fibrotic infiltrate.24,35 These changes cause dysfunction of esophageal motility, mainly in the lower part.36 An autoimmune neurological component in gastrointestinal manifestations has also been described,27,28 the involvement of the acetylcholine receptor 3 antimuscarinic antibodies has been postulated37–39 by inhibiting the contractibility of smooth muscles.34 A decrease in the amplitude of the contractibility and a low resting pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter have been found,40,41 which are translated into symptoms, such as dysphagia, cough, heartburn, regurgitation or dyspepsia.34,42

Esophageal dysphagia is present in 4.3 % of patients with SSc,43 affecting swallowing. If it exists an exclusive dysphagia for solids, it is advisable to rule out an obstructive cause such as esophageal stricture.44 The presence of esophageal stenosis, esophageal candidiasis, immunosuppressive treatment and chronic acid suppression due to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has been associated with the presence of dysphagia in SSc.45

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is present in up to 70 % of patients1,46–51 and it is a frequent clinical manifestation at the esophageal level.52,53 Due to the decrease in the pressure of the LES, the number of episodes of reflux increases and together with the lower motility capacity of the esophagus, gastric acid remains longer in the esophagus and can move to the trachea and pharynx.54 The neutralization of gastric acid by saliva is decreased and incomplete, worsened by dry oropharyngeal syndrome.55

Complications that have been associated with GERD are esophageal stenosis (30 %), Barrett esophagus (37 %), cough, bronchospasm or laryngospasm.48,56–60

In addition, esophageal involvement may contribute to interstitial lung disease (ILD).61,62 A retrospective review with more than 400 patients with SSc showed that a larger esophageal diameter was correlated with reductions in pulmonary functional values.44,62 Another study identified similar levels of pepsin in bronchial and gastric fluids in patients with SSc.63 pH monitoring has been suggested as a prognostic factor in patients with SSc with ILD.64

It is recommendable to perform esophageal evaluation of all patients with SSc, being the most useful procedures manometry, pH monitoring and endoscopy.42 Esophageal manometry is essential for the diagnosis of esophageal dysmotility,65 especially in the beginning stages. The high resolution manometry allows a better evaluation of the entire esophagus,66–69 however, this technique is not yet validated65; the esophageal pH monitoring, with or without impedance, allows the detection of gastroesophageal reflux. Abnormal pH monitoring has been observed in up to 85 % of patients with SSc46,70,71 but in clinical practice it is only used in patients with symptoms of resistant reflux.42 Endoscopy is the best tool to assess dysphagia or identify the presence of GERD and their complications. Barrett’s esophagus is caused by chronic GERD, requiring periodic endoscopic controls due to the presence of a lesion of the normal esophageal mucosa and its replacement by metaplastic mucosa.29 The presence of metaplastic mucosa is a relevant risk factor for adenocarcinoma in the esophagus.

Other less useful diagnostic tools are scintigraphy; magnetic resonance imaging; the esophagogram with barium or the endoscopic capsule.65,72

First measures for treatment of esophageal involvement in SSc are based on the hygienic-dietary recommendations like eating soft foods in small quantities; abundant fluid intake; avoid certain substances such as alcohol, caffeine, spices, among others; raise the head of the bed or eat about 2−3hours before bedtime.32,73 There are no randomized clinical trials that have found evidence of the different pharmacological options to treat esophageal complications in patients with SSc. The use of PPIs to treat GERD is recommended74 and may be useful for ulcers and esophageal stricture prevention.44,75 A decrease in esophagus adenocarcinoma has been seen in patients undergoing treatment with PPIs.76 The H2 receptor antagonist (anti-H2) would be indicated in cases refractory to PPIs.77

The use of prokinetics can relieve different motility disorders (dysphagia, GERD, abdominal distension, pseudo-obstruction, early satiety).74 Cisapride (5-HT4 agonist and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist) may improve gastric and esophageal motility, but also causes decreased tone of the lower esophageal sphincter and small intestine motility.78–81 Domperidone (D2 receptor antagonist) in association with PPIs has been shown to be useful to decrease the severity of motility symptoms.82 Metoclopramide has shown a tonal increase in the lower esophageal sphincter in patients with SSc and also improves motility.83–85 Prucalopride (5-HT4 agonist) showed an improvement in motility in a series of patients with SSc.86 Other alternatives are buspirone and baclofen that can improve GERD by increasing the lower sphincter tone and enhancing the esophageal contractions.72 According to the latest European Scleroderma Trials and Research Group (EUSTAR) recommendations the use of prokinetics in patients with SSc is suggested for symptomatic motility disorders.74 Regarding the use of immunomodulatory therapies, there is an observational study with the use of intravenous immunoglobulins in patients with SSc and GIT condition, evidencing a decrease in the frequency and intensity of GERD symptoms.87

Some patients with GERD refractory to medical treatment require invasive techniques such as esophagectomy, fundoplication, or Roux-en-Y bypass.29 Patients with esophageal stenosis may benefit from endoscopic dilations.29

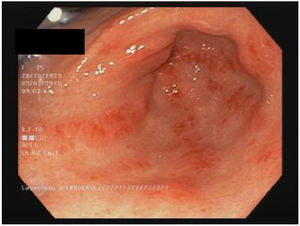

StomachAround 50 % of patients with SSc have stomach involvement.13,60 The most common manifestations are delayed gastric emptying and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE or watermelon stomach; Fig. 1).8,10,88 Although the specific mechanism of gastric disease is unknown, microvascular damage, a compromise of the peripheral nervous system and myogenic dysfunction have been proposed as possible causes.41 Gastroparesis can affect 10–80 % of patients.3,8,14,48,61,89,90

The clinical manifestations present are abdominal pain/distension, bloating, and more commonly, early satiety and postprandial nausea.91 The severity of the symptoms does not correlate with the degree of involvement.92,93

Scintigraphy is the recommended test to assess motility at this level91 and endoscopic pill can be useful in patients who do not tolerate scintigraphy.72 In SSc, the delayed emptying of liquids correlates with early satiety and anorexia.72 Other diagnostic tools are: breath testing, esophago-gastrointestinal manometry, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or gastric magnetic resonance imaging.94–96

Treatment with hygienic-dietary measures and avoiding drugs that affect intestinal transit such as opioids or neuroleptics72 are the first measures to suggest. Metoclopramide (D2 receptor antagonist and 5-HT4 agonist) is the first-line drug for gastroparesis.91 Metoclopramide has been shown to improve nausea and post-prandial distention in patients with SSc.83,84 Cisapride and domperidone may be considered in some cases.72 In refractory patients, macrolides such as erythromycin have been shown to improve solid gastric emptying97,98 but they can reduce the transit of the small intestine and can change the QT interval.99 Buspirone (agonist of 5-HT1a receptor) can cause relief in functional dyspepsia but also causes a decrease in gastric emptying of fluids.72 Levosulpride (D2 receptor antagonist) seems to decrease gastric filling time. In studies without SSc patients, levosulpride has demonstrated superiority over metroclopramide or domperidone.72 Prucolopride (5-HT4 receptor agonist) improves duodenal motility and decreases the effects of gastroparesis.86 Ghrelin (neurohormone secreted by the stomach and small intestine) has been shown to improve gastric emptying in patients with gastroparesis with or without SSc.72,100 The use of antiemetic therapies (ondansetron, promethazine, meclizine or cannabinoids) to improve gastroparesis is not rare. More invasive procedures like botox injections and gastric stimulator implants, can be considered in severe cases.72

GAVE is found in up to 22.3 % of patients.88 GAVE probably is produced due to an alteration of the microvascular component of the SSc.8,101 A recent study found a greater presence of GAVE in patients with early diagnosis of SSc and patients with the diffuse subset (dcSSc).10 A negative association with anti-topoisomerase antibodies (ATA)102 and with anti-U1-ribonucleoprotein88 were also published. The association of GAVE with other autoantibodies is controversial.103 Main clinical manifestations include iron deficiency anemia or upper gastrointestinal bleeding.103 Is noteworthy the recommendation to rule out the presence of SSc in patients with GAVE.88,101 The diagnosis is endoscopic, showing multiple confluent small vascular ectasias with longitudinal orientation from the folds of the antrum to the pylorus.104 The initial treatment is supportive therapy, with iron supplements and/or red blood cell transfusions. If conservative therapy fails, endoscopic therapy would be required with laser ablation, argon plasma photocoagulation or endoscopic band ligation, especially for patients with GAVE-related bleeding.44 The antrectomy is only reserved for severe cases.105

Small intestineComplications of the small intestine in SSc are frequent and the duodenum is the most affected (40–88 %).106 It is believed that small intestine alterations are the result of progressive histological lesions similar to those of other organs in SSc. Sjögren proposed a damage progression based on vascular involvement (grade 0), neurogenic deterioration (grade 1) and myogenic dysfunction (grade 2) with the replacement of normal smooth muscle with collagen fibrosis and atrophy.41 Dysmotility of the small intestine is due to neuropathic and myopathic changes, by vascular ischemia and causes nerve damage, smooth muscle atrophy and finally fibrosis.106 This contributes to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).107

Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) is characterized by a malfunction of the gastrointestinal motility with symptoms and signs of acute or chronic intestinal obstruction in the absence of mechanical occlusion.108 CIPO is usually secondary to atony, dilation and delayed transit within the small intestine, perforation may also occur due to serous fibrosis with loss of adhesion of the wall in the muscular layer.101 Jejunal diverticulum may develop due to protrusion of the intestinal wall.101 X-Ray can suggest its presence and baritated contrast shows dilated intestine loops with dilation and food accumulation.55 Alternative diagnosis methods are scintigraphy, capsule endoscopy or enterography.107

To avoid small intestine manifestations is very important that SSc patients maintain adequate fluid intake and avoid laxatives and high fiber foods because they can worse symptoms.29 In case of small intestine dysmotility and CIPO, the use of prokinetics can also be useful. Octeotride and cisapride help duodenal motility.81,109 Octreotide in combination with erythromycin improves abdominal pain and nausea109 but its prolonged use may favor cholelithiasis and intestinal perforation.110

The presence of SIBO occurs in between 43 and 60 % of patients with SSc and can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, bloating, swelling and signs related to malabsorption (weight loss, steatorrhea, vitamin deficits).115 SIBO severity can be correlated with symptomatology.107,111,112 The gold standard for diagnosis is jejunal aspirate culture113 but in clinical practice other tests like hydrogen or methane breath test are used.114 The use of intermittent or rotary antibiotics can be useful.111,112

Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis is characterized by multiple cysts with air content in the intestinal wall due to the elevation of intraluminal pressures caused by bacterial overgrowth.116 It is a rare radiographic finding with radiolucent cystic images due to the presence of air in the submucosa or sub-serosa, conservative management being recommended. Also, it can produce a pneumoperitoneum in case of rupture.13,117,118

ColonLarge bowel involvement (20–50 %) is usually asymptomatic119 but the presence of cardiac, pulmonary, renal or cutaneous involvement is related to the presence of colonic symptoms.13

Large bowel symptoms are probably caused by inflammation in the intestinal wall causing muscular atrophy, fibrosis and dysmotility. Colonic hypomotility can cause a delay in intestinal transit time and constipation with an increased bacterial overgrowth that can produce malabsortive diarrhea.120,121 Diverticulosis presents a risk of ulceration and infection due to fecal retention, and during the evolution of the disease the intestinal wall becomes stiff, doing a false resolution of the diverticulum.122

Large bowel chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction is a rare complication that is expressed in the form of nausea, vomiting, bloating and changes in depositional rhythm, recommending conservative management, and electrical stimulation or surgery should be used as a last therapeutic resource for CIPO.13,121,122 In case of recent onset of constipation in patients with SSc, endoscopic and/or imaging studies are necessary to exclude malignancy, stenosis, diverticulosis and other colon diseases.121 The management is symptomatic29,121 using stimulant laxatives,77,123 in addition to other agents that help constipation such as metoclopramide, domperidone and prucalopride.99,123,124

AnorectalAnorectal symptoms occur in 50–70 % of patients and affect the internal anal sphincter (IAS) producing fecal incontinence, constipation and rectal prolapse.125 IAS compromise may be due to a primary pathology of the muscles or neurons or secondary to ischemia/inflammation of the anorectal wall.7,126 The decrease in the recto-anal inhibitory reflex is additional evidence of peripheral nerve deterioration in SSc.127 Constipation and rectal prolapse occur as the disease progresses causing altered relaxation and restricted distension.128 Manometric studies show an inhibition of anorectal reflex and normal compression pressures,129 endoanal ultrasound or rectal magnetic resonance imaging can also assess the integrity and structural abnormalities.130,131 Diet recommendations can improve intestinal motility and the integrity of IAS, including fecal incontinence; antidiarrheals may be useful, but they should be used carefully as they can exacerbate constipation and induce rectal prolapse.13 Sacral nerve stimulation improves symptoms, but there is no long-term evidence.123

LiverLiver disease in SSc is rare (1.5 % of patients) and PBC is the most frequent involvement.44 In fact, SSc is the systemic autoimmune disease most associated with PBC (7–17 %).132 lcSSc is more associated,133–136 as well as the presence of anti-centromere antibodies (ACA).137,138 Anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA) are present in up to 94 % of patients with PBC associated with SSc.32,139,140 The presence of AMA has been observed in up to 13 % and up to 3 % of patients with lcSSc and dcSSc, respectively, without presenting a clear relationship with underlying PBC.29

Patients usually are asymptomatic and the diagnosis is made by unexplained elevation of hepatic alkaline phosphatase and presence of AMA.141 Anti-gp210 and anti-sp100 antibodies increase sensitivity up to 100 %.29 Liver biopsy is only necessary for diagnosis when there are no antibodies specific for PBC.29

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) remains the treatment of choice for PBC, and liver transplantation is recommended in patients with late stage disease. Prednisone and budesonide have been shown to improve histology at an early stage, but there are no long-term studies. Sulindac and benzofibrate improve liver function in limited groups of patients with an incomplete response to UDCA.141 Patients with PBC and SSc have shown a slower progression in comparison with patients with isolated PBC.142 In patients with SSc and PBC is recommended monitoring every 1–2 years with liver function test.142 Autoimmune hepatitis is rare and usually associated with a lcSSc.143,144 Other liver diseases related toSSc are: Regenerative nodular hyperplasia, idiopathic portal hypertension, spontaneous liver rupture, massive hepatic infarction and hepatic duct obstruction related to vasculitis.145

PancreasPancreatic disease in SSc is rare and sometimes can be confused with SIBO.32,146 In a case of suspected SIBO, pancreatic insufficiency should be ruled out if there is no response after starting antibiotics.147 Cases of pancreatic necrosis, acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis have also been reported.148

ConclusionsGastrointestinal involvement is common in SSc and can affect the entire digestive tract. The esophagus is the most compromised area. Diverse clinical manifestations can appear and they have a great impact on the quality of life of the patients. The evaluation of the esophagus by manometry is recommended in all patients with SSc and the use of other tools to determine the gastrointestinal compromise depends on the different clinical manifestations presented by the patients. The management is based on hygienic-dietary measures as well as on the treatment of the different symptoms. It is important to identify the gastrointestinal condition to prevent long-term complications, as well as to exclude the causes of symptoms not related to SSc.

Please cite this article as: Tandaipan JL and Castellví I. Esclerosis Sistémica Y Participación Gastrointestinal. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2020;27:44–54.