Acute mesenteric ischemia is a medical emergency that accounts for less than 1/1000 hospital admissions. The disease affects adults older than 50 years predominantly with cardiac compromise, in whom the presence of acute abdominal pain is the cardinal manifestation, and should make the clinician suspect this entity. Its presentation in adolescents is unusual; therefore, in these cases, the possibility of an underlying thrombophilia should be part of the differential diagnosis. The case is presented here of a young female with a protein C and S deficiency as the cause of mesenteric thrombosis.

La isquemia mesentérica aguda es una urgencia médica que se presenta en menos de 1/1.000 ingresos hospitalarios. Es una entidad clínica infrecuente, predominante en adultos mayores de 50 años con afectación cardíaca, en quienes la presencia de dolor abdominal agudo es la manifestación cardinal y debería hacer sospechar dicho diagnóstico. La presentación en adolescentes es inusual, por lo que, en estos casos, la posibilidad de una trombofilia subyacente debe formar parte del diagnóstico diferencial. Presentamos el caso de una paciente joven con deficiencia de proteínas C y S como agente causal de trombosis mesentérica.

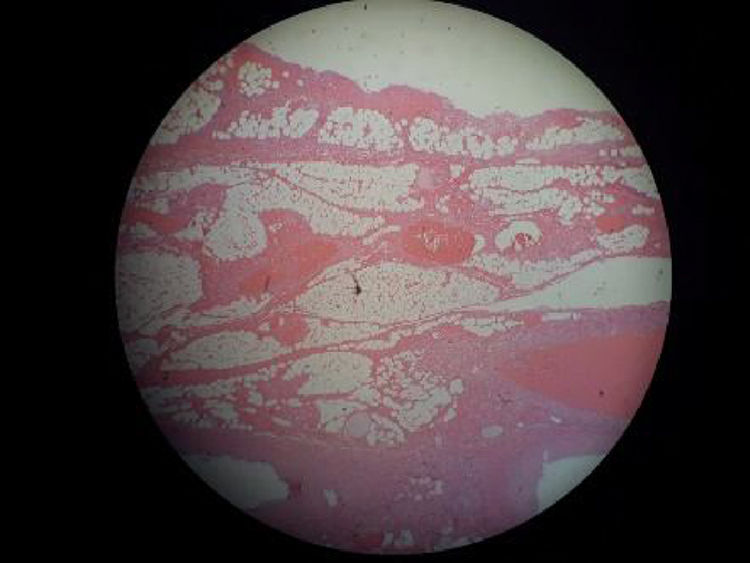

Acute mesenteric ischemia is a clinical condition that occurs when the blood flow of the mesenteric vessels is insufficient for the tissue metabolic demands, generating lesions that depend on the affected vessel, the degree of occlusion, the mechanism of ischemia (occlusive or non-occlusive), its duration and the presence of collateral circulation. The mucosa and submucosa, which in normal conditions receive 70% of the vascular flow, are the layers most vulnerable to the effects of hypoxia; therefore, the initial lesions settle in the mucosa, where areas of edema, submucosal hemorrhage, ulceration and finally necrosis can be observed. Only in cases of persistent ischemia, the damage can compromise all layers of intestinal tissue (transmural ischemia), with the possibility of perforation, peritonitis and derived sepsis.1

The possible causes can be divided into 4 large groups: (1) hereditary thrombophilias, such as antithrombin III deficiency, plasminogen deficiency, protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, hyperfibrinogenemia, factor V Leiden mutation, sickle cell anemia, as well as some infrequent genetic alterations, such as the prothrombin G20210A mutation and the JAK2 V617F mutation; (2) Acquired thrombophilias and systemic hypercoagulability states, including pregnancy, use of oral contraceptives, consumption of cocaine (or other substances with the potential to cause vasospasm), antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, monoclonal gammopathies, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, polycythemia vera, nephrotic syndrome, essential thrombocythemia and embolism, among others; (3) intra-abdominal causes: congenital anomalies, cirrhosis, inflammatory bowel disease, intra-abdominal infection, pancreatitis, trauma, intestinal volvulus and post-surgical status, and (4) idiopathic causes that could account for up to 49% of cases depending on the series,2–4 representing one of every 1000 hospital admissions and up to 5% of hospital mortality. The lack of timely recognition of this disease can lead to catastrophic complications, with a mortality rate of up to 80% of the affected individuals.5,6

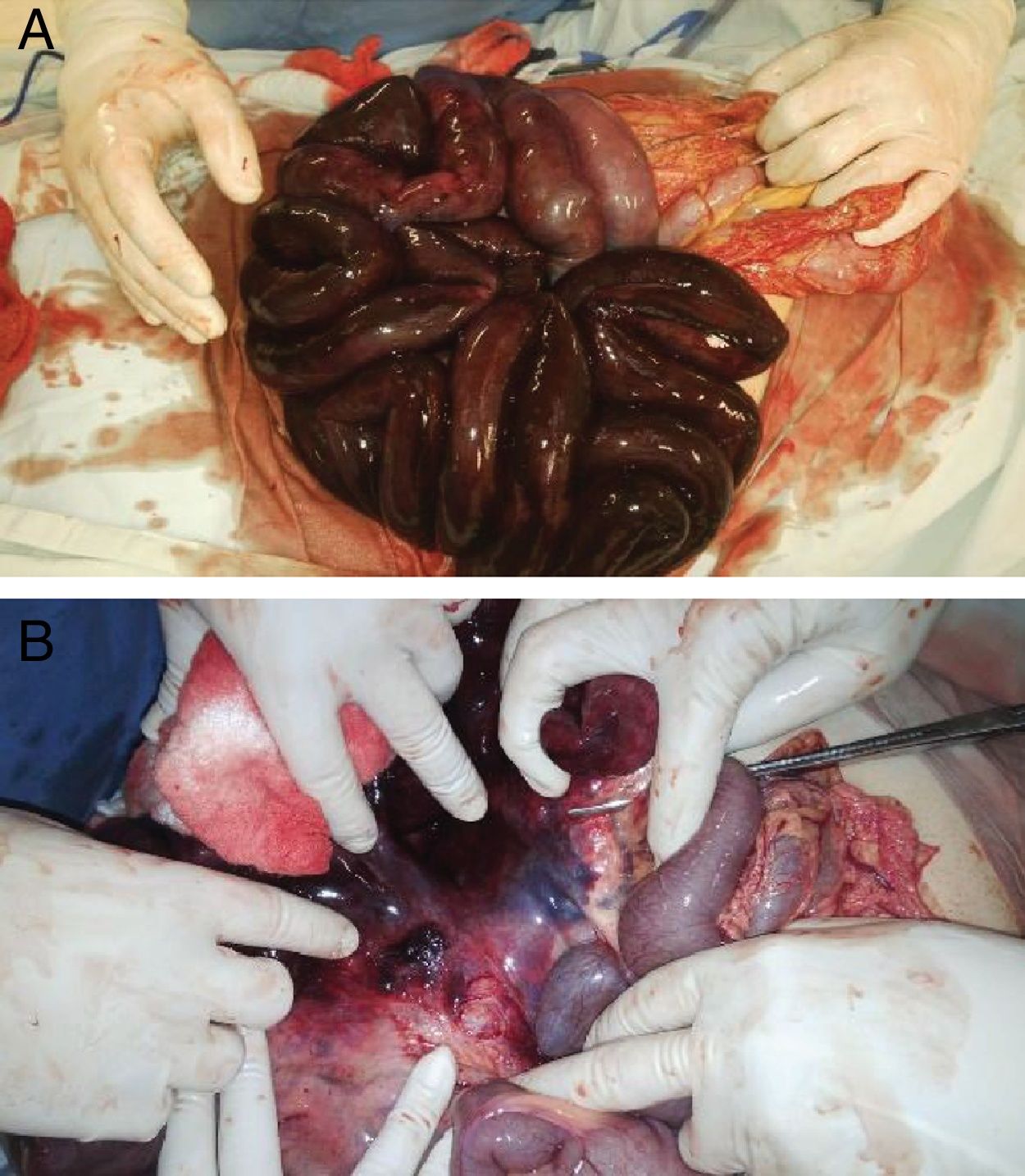

Case presentationA 15-year old female patient who enters the Emergency Department of a referral hospital due to diffuse abdominal pain associated with multiple emetic episodes, hypotension (60/30mmHg), tachycardia (160bpm), tachypnea (22bpm) and leukocytosis (25,590/dl), in the absence of fever. The patient is taken to emergency surgery for suspected sepsis of abdominal origin (appendicitis), finding an acute intestinal ischemia secondary to thrombosis of the superior mesenteric vasculature (arterial and venous), with involvement of the small intestine from the duodenum to the terminal ileum, requiring resection of this area due to necrosis (resection of 75% of its extension) (Fig. 1). In the anamnesis, the patient refers that she was previously healthy, without important personal or family antecedents.

After the surgical intervention, the patient was taken to the Intensive Care Unit, where she was stabilized and anticoagulated, and complementary studies were requested to rule out hypercoagulable states and autoimmune causes (Table 1). The surgical material was sent for histopathological and immunohistochemical study, being reported transmural occlusive intestinal ischemia with arterial and venous commitment (Fig. 2).

Laboratory tests results.

| Laboratory study | Result |

|---|---|

| C-reactive protein | 14.3mg/dl |

| Prothrombin time | 13.5s |

| Partial thromboplastin time | 31.5s |

| INR | 1.31 |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Negative |

| Anti-DNA antibodies | Negative |

| Anti-Sm antibodies (EIA) | 3.7AU/ml (<12) |

| Anti-Ro (IgG) antibodies (EIA) | <3.0AU/ml (<12) |

| Anti-La (IgG) antibodies (EIA) | <3.0AU/ml (<12) |

| Anti-RNP (IgG) antibodies (EIA) | <3.0AU/ml (<12) |

| Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (IIF) | Negative |

| Anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies (EIA) | 1.77U/ml (<5) |

| Anti-proteinase 3 antibodies (EIA) | 1.34U/ml (<5) |

| Lupus anticoagulant | Negative |

| IgM anticardiolipin antibodies | 10.4MPLU/ml |

| IgG anticardiolipin antibodies | <3MPLU |

| IgM B2-glycoprotein | 1.00U/ml (<5) |

| IgG B2-glycoprotein | 1.90U/ml (<5) |

| C3 | 56.3 |

| C4 | 7.9 |

| Protein C (TC) | 47.70% (70–140) |

| Protein Ca resistance (RI; CM) | 1.07 (<0.7) |

| Functional protein S | 46.0IU/dl (52–130) |

| Factor V Leiden | Negative |

| Proacelerin factor V | 38.8IU/dl (50–150) |

| Coagulation factor VIII | 194.4IU/dl (50–150) |

EIA: enzyme immunoassay; IIF: indirect immunofluorescence; INR: international normalized ratio; CM: coagulometric method; RI: normalized ratio; CT: chromogenic technique.

The patient was diagnosed with acute mesenteric ischemia secondary to a combined protein C (47.70%) and protein S (46.0IU/dl) deficiency, ruling out causes such as systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, primary systemic vasculitis of large, medium and small vessels, as well as other thrombophilias (Table 1). Due to the extensive resection of the small intestine, the possibility of performing an intestinal transplant was raised, which is why the patient was referred to an institution with the capacity to perform this type of procedures and implement an adequate interdisciplinary management. However, at the time of writing this case report, the transplant has been deferred due to the excellent response the patient has had to enteral nutrition, continuing antithrombotic therapy.

DiscussionThe deficiency of proteins C and S predisposes to venous thrombosis in the lower limbs, particularly in early adolescence, and in general the initial presentation occurs before 40 years of age. Despite this, the deficiency of one or the other can cause formation of thrombi in various vascular beds, particularly in the form of venous thrombosis of the lower limbs.7 The presentation as mesenteric ischemia is quite unusual and the associated arterial involvement could be considered exotic, with few cases reported in the world literature to date.

It is clinically impossible to distinguish between protein C or protein S deficiency, or other causes of primary hypercoagulable disorders. The possibility of one of these disorders should be suspected in a patient with one or more of the following criteria: (1) venous thrombosis at an early age (<50 years), especially when there is no precipitating cause or it is weak; (2) strong family history of venous thrombosis (first-degree relatives affected at early ages); (3) recurring thrombotic events, especially at early ages, and (4) venous thrombosis at unusual sites, such as the splanchnic or cerebral bed.8

Another aspect to consider is the existence of underlying, or de novo, autoimmune disease, particularly in women of reproductive age. In the case presented, screening studies for diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus were carried out, with negative reports of ANA, ENA and anti-DNA, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (lupus anticoagulant, IgM and IgG anticardiolipin antibodies, IgM and IgG B2-glycoproteins, as well as IgG for the following phospholipids: phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidic acid and phosphatidylinositol, all these being negative), primary systemic vasculitis (Takayasu arteritis, without absence of pulses, without a difference >10mmHg in blood pressure between extremities, without carotidynia or carotid or subclavian murmurs; Kawasaki disease, polyarteritis nodosa and vasculitis of small vessels were also ruled out; the antibodies for systemic vasculitis and their specificities were negative). It is important to mention this aspect, since these types of entities, especially the vasculitis of large vessels, can cause, not infrequently, mesenteric ischemia.9,10

Our patient had negative studies for thrombophilias, such as the factor v Leiden mutation and mutations of the coagulation factor viii, which are the most frequently found in autoimmune diseases. The only positive studies in this case were the quantitative deficiencies of proteins C and S. It is important to mention that the levels of anticoagulant proteins may be decreased after a thrombotic event, as well as with the use of oral anticoagulants, particularly warfarin.7 Despite this, confirmatory studies were carried out after the period of convalescence, obtaining again a quantitative deficiency of the 2 molecules already mentioned.

While systemic vasculitides are among the most common causes of arterial and venous thrombosis, and they constitute a differential diagnosis to consider in previously healthy young patients, primary thrombophilias are part of the differential diagnosis to take into account. There are few reports in the literature of protein C or S deficiency with this clinical presentation; most of the cases have had unfavorable outcomes, so it is essential to consider these entities as possible causes, in order to provide timely treatment and improve the quality of life of these patients.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

We thank Dr. Mónica Duque, pediatric intensive care specialist at the Clínica los Rosales, Pereira, Risaralda.

Please cite this article as: Rubio LM, Bedoya GA, Paz DF, Rivera LM. Deficiencia de proteínas C y S como causa de trombosis mesentérica: diagnóstico diferencial de las vasculitis sistémicas. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2019;26:278–281.