Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that can affect the skin; the cutaneous manifestations are very diverse. Diagnosis of the disease is challenging because its presentation is polymorphous and therefore it is necessary to make a correlation with its histology. It is important to recognize skin lesions, as they are often the first manifestation of systemic disease, and they are also accessible for taking a biopsy. We present a novel case of subcutaneous sarcoidosis, that is often underdiagnosed and rarely appears in the lower limbs. The different manifestations of cutaneous sarcoidosis and their treatment are also described.

La sarcoidosis es una enfermedad granulomatosa que puede afectar diferentes órganos, entre ellos la piel; las manifestaciones cutáneas son muy diversas. Su diagnóstico es un reto porque la presentación es polimorfa y se necesita la correlación con la histología. Es importante reconocer las lesiones en la piel pues muchas veces son la primera manifestación de un compromiso sistémico; además, es un sitio accesible para la toma de biopsia. Se presenta un caso novedoso de sarcoidosis subcutánea, una manifestación muchas veces subdiagnosticada y que rara vez aparece en miembros inferiores. También se describen otras manifestaciones de la sarcoidosis cutánea y su tratamiento.

A 38-year-old male patient who consulted due to a clinical picture of two months of evolution consisting in blurred vision associated with persistent bilateral red eye, throbbing headache with an intensity of 6/10 on the analogue pain scale, and arthralgia in the ankles and wrists, predominantly in the morning, without morning stiffness. In addition, the patient reported the appearance of “painful masses” in both lower limbs. He denied fever, weight loss, night sweats and respiratory, gastrointestinal, or urinary symptoms.

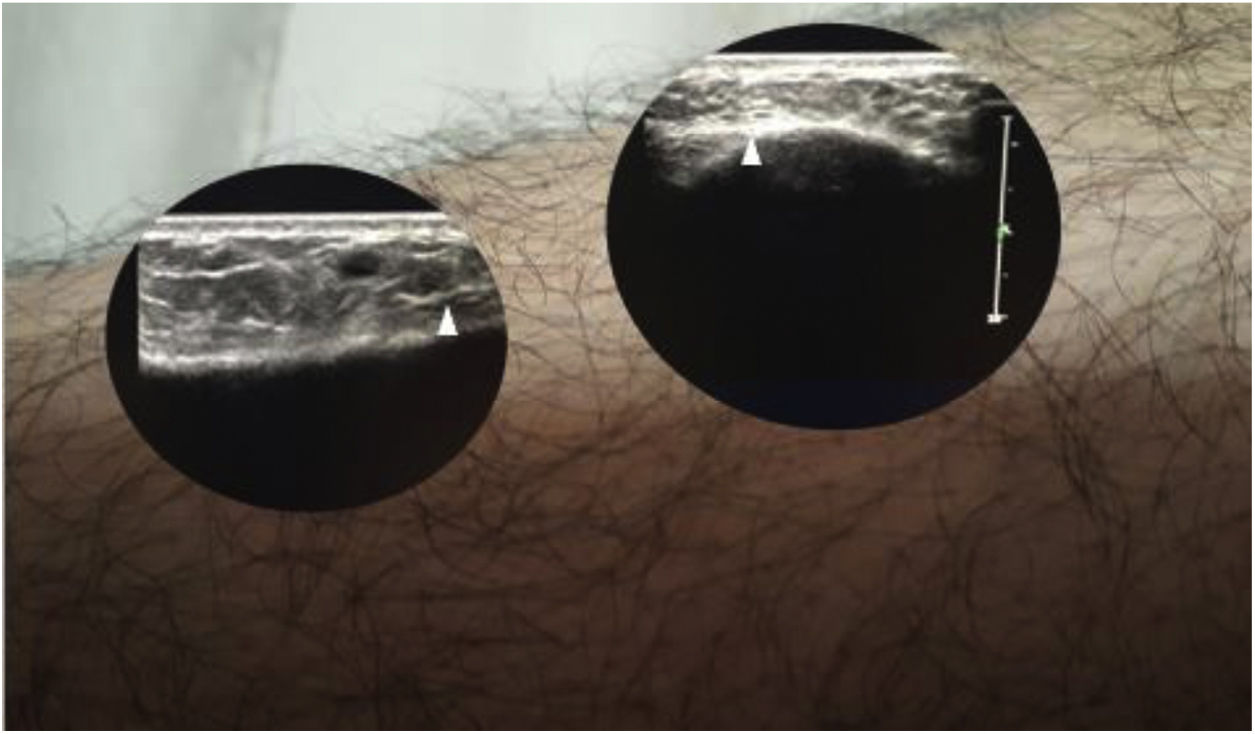

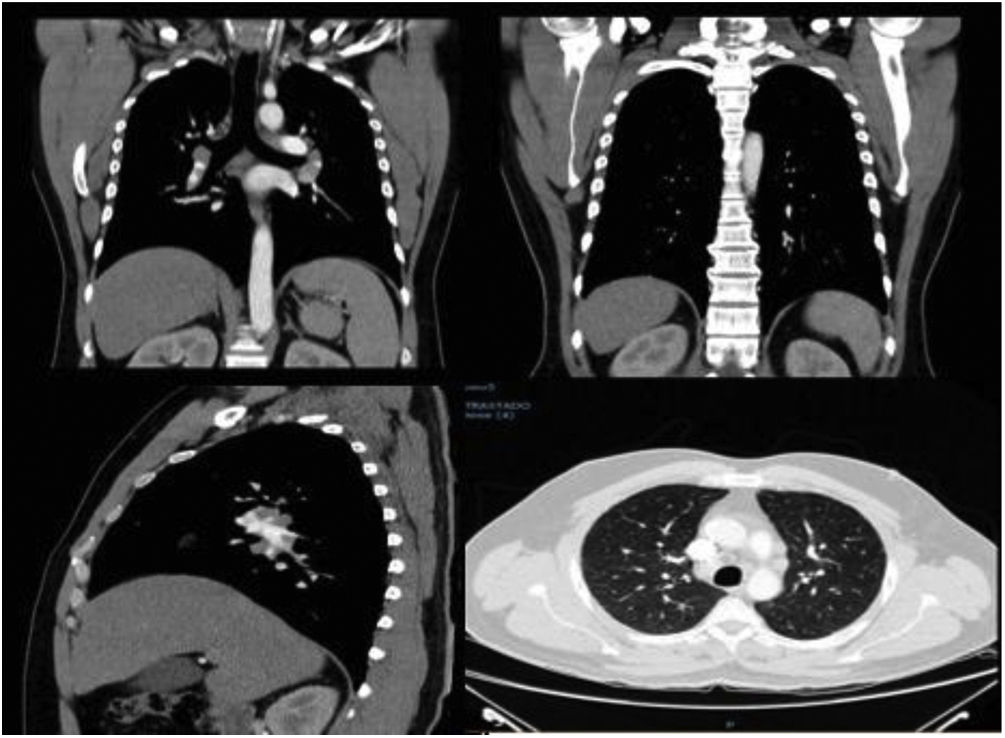

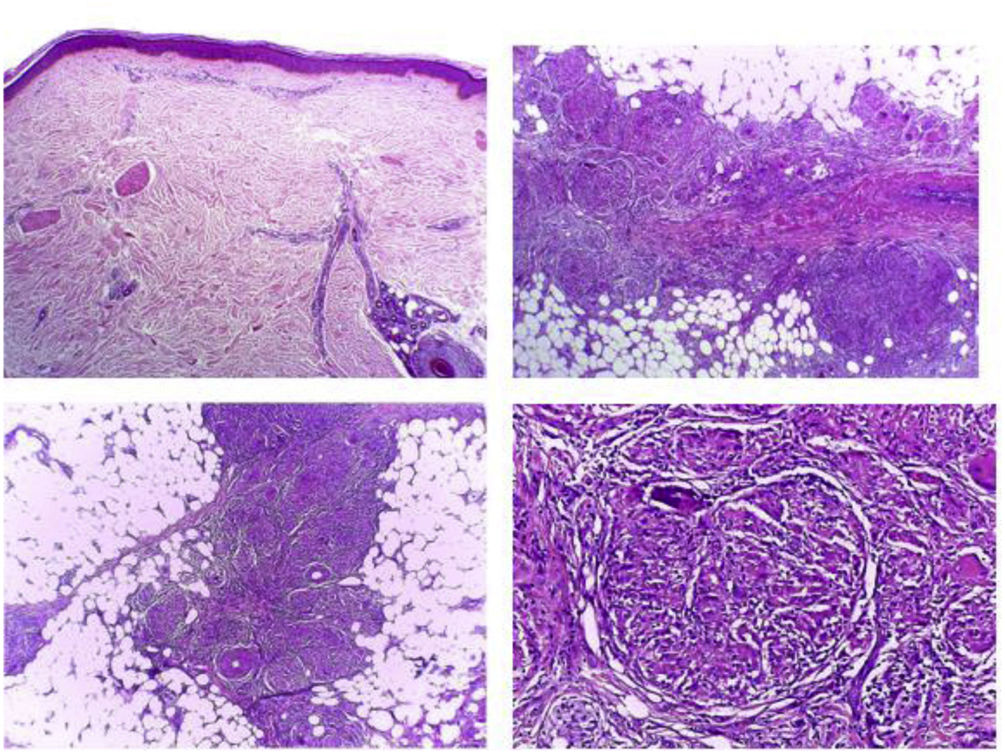

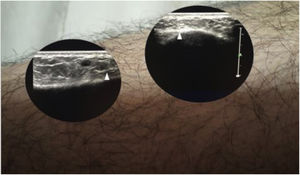

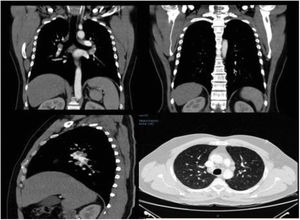

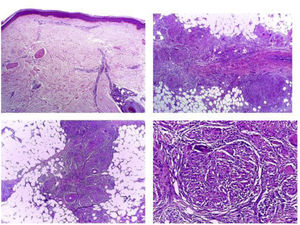

The patient was admitted to the hospital by the Ophthalmology Service with a diagnosis of bilateral panuveitis and papillitis. On physical examination, he presented subcutaneous nodules tender on palpation in both lower limbs, with no epidermal changes suggestive of erythema nodosum (Fig. 1). To better characterize the lesions, a soft tissue ultrasound scan was performed. (Fig. 2) In addition, asymmetric growth of the parotid glands was observed, with the left being more prominent. Paraclinical studies showed hypercalciuria of 448 mg in 24 h, with normocalcemia of 8.76 mg/dL. The chest tomography showed bilateral paratracheal, mediastinal, and hilar adenopathies (Fig. 3). The skin biopsy revealed multiple sarcoid granulomas at the subcutaneous level (Fig. 4). The diagnosis of subcutaneous sarcoidosis with systemic manifestations was established and management was started with prednisone at 1 mg/kg/day, with which there was complete resolution of the skin lesions.

The first descriptions of cutaneous sarcoidosis were reported at the end of the 19th century by Sir Jonathan Hutchinson and Ernest Besnier. Caesar Peter Møller Boeck was the first to describe the histopathology, which is characterized by non-caseating granulomas in the absence of microorganisms.1 In 1950, Sven Löfgren reported an acute manifestation of sarcoidosis that did not correspond to a granulomatous lesion, called erythema nodosum, also associated with bilateral hilar adenopathies, fever and polyarthralgia, currently known as Löfgren's syndrome.2

Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis can be classified as specific lesions, when they present the characteristic granulomas with non-caseous necrosis, and as non-specific when they present a different histology.3 Specific skin lesions occur in 9–37% of the patients with this entity, they are the second most frequent manifestation, after the pulmonary,3,4 and occur with the same frequency in both sexes. Chronic lesions are more common in African American patients.5,6

Up to 80% of the patients with systemic sarcoidosis present skin manifestations before diagnosis, and in 30% of cases such manifestations represent the earliest symptom.7,8 Demonstration of granulomas in tissues by biopsies is required to establish the diagnosis. A skin biopsy with non-caseating granulomas sometimes obviates the need for more invasive biopsies of other organs, if the clinical symptoms and the radiology are typical of sarcoidosis.9 Aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes, giant cells, and mature macrophages surrounded by infiltrates of CD4+ lymphocytes, and to a lesser extent, CD8+, are also found in the histology.10,11

The histological differential diagnosis includes other granulomatous disorders, such as tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteria, fungal infections, foreign body reaction, rheumatoid nodules and leishmaniasis; and the finding of a foreign body does not exclude the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.12,13

Due to the fact that skin sarcoidosis manifests itself with such variable and polymorphous symptoms, this disease is also known as the great imitator.14 A novel case of subcutaneous sarcoidosis is presented, since it is a manifestation that is often underdiagnosed and rarely appears in the lower limbs, where it is usually confused with erythema nodosum. Below, taking advantage of the case, the specific and non-specific lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis are described.

Specific lesionsMaculopapular lesionsIt is the most common manifestation, with infiltrated lesions with minimal epidermal changes, erythematous or brown to purple which measure less than 1 cm. Less frequently, they appear as normochromic or yellowish lesions.15 They have a disseminated distribution and are located predominantly on the eyelids, periorbital region, philtrum, scalp, neck, trunk, buttocks, extremities, or even on the mucous membranes.4 Sometimes the lesions are transient, but they can grow to form larger plaques.15

They are associated with acute forms of the disease such as erythema nodosum, uveitis, lymphadenopathies, and parotid enlargement. The recently described papular sarcoidosis of the knees is associated with erythema nodosum.16

Other maculopapular lesions that appear on the face such as xanthelasma, acne, rosacea, lupus, syringoma, lichen planus, granuloma annulare, and sebaceous adenoma should be included in the differential diagnosis.17

Subcutaneous nodulesThe frequency of this presentation ranges between 1.4 and 16%, and in many occasions is underdiagnosed. This variant is also known as Darier-Roussy disease, and is more common in middle-aged women.18

It presents itself as subcutaneous nodules of 0.5–2 cm, of firm consistency, mobile and non-inflammatory. Between one and 100 nodules can be found, which, in addition, can be grouped. There are no epidermal changes, so the skin looks normal. They appear in the dermis or in the subcutaneous tissue of the extremities or the trunk. They are generally located on the forearms and rarely occur in the lower limbs, as in the case described. They are not very painful, in contrast to erythema nodosum.19

They frequently appear at the onset of the disease, together with other systemic manifestations, or even as the first manifestation, and may persist for a long time.20

They must be differentiated from cutaneous tuberculosis, deep mycoses, skin metastases, epidermal cysts, lipomas, rheumatoid nodules, and indurated erythema.21,22

Scar sarcoidosisInfiltration of old scars is a characteristic finding of sarcoidosis. The scars take on an erythematous or purpuric appearance and on palpation they are indurated, which is why they can be confused with a hypertrophic or keloid scar.3

It can predict systemic disease and be related to activity. In the acute phase, it can follow erythema nodosum, while in the chronic phase it is associated with mediastinal and pulmonary involvement, uveitis, and bone cysts.23 However, other authors consider that this type of sarcoidosis, when it occurs in isolation, constitutes a benign process with a good prognosis.24 Granulomatous infiltration of old tattoos or at sites of foreign material has been described as a variant of sarcoidosis.23

PlaquesThe presentation in plaques has a frequency similar to that of the papules. They are single or multiple, round or oval, brown to red, larger than 5 mm, and are thicker and more indurated than the papules. They are located on the extremities, the face, the scalp, the back and the buttocks.25 They may have an annular configuration and sometimes occur with a scar. They are usually persistent and are associated with chronic forms of lung disease, splenomegaly, and uveitis.26 Other diseases that present with generalized plaques or ring-shaped lesions such as psoriasis, lichen planus, discoid lupus, granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, mycosis fungoides, Kaposi's sarcoma, secondary syphilis, morphea, leprosy and leishmaniasis should be considered in the differential diagnosis.26

Lupus pernioIt is the cutaneous lesion most characteristic of sarcoidosis. It is found more commonly in black women with chronic sarcoidosis. Sometimes they have prominent telangiectasia and desquamation with beaded appearance.27

It presents as red or violaceous, indurated plaques or nodules, affecting the nose, cheeks, earlobes, lips and forehead. Less commonly, they appear on the hands and feet, but there may be lytic lesions with phalangeal dystrophy.4 In the nose it could cause ulceration of the septum. It can coexist with other sarcoidosis lesions such as the variant in plaques.28 It is associated with pulmonary fibrosis, chronic uveitis and bone cysts. It has a prolonged course and is associated with chronic disease requiring steroids.29 It is important to highlight that not all sarcoidosis lesions located in the nose will be lupus pernio.30

It should be differentiated from lupus erythematosus, lupus vulgaris, lymphocytic infiltrate, rhinophyma, tertiary syphilis, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis when it destroys the nasal septum.31

Less frequent lesionsAngiolupoid sarcoidosisIt is a variant of sarcoidosis in plaques with a large component of telangiectasia. It appears in women and affects the nose, the central face, the ears or the scalp. It can be confused with rosacea or with a large basal cell carcinoma.32

Hypopigmented sarcoidosisIt manifests as well-defined, round or oval, hypopigmented macules on the extremities, generally in patients with high phototypes. The differential diagnosis can be established with other hypopigmented lesions such as leprosy, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, pityriasis, and chronic lichenoid. In these cases it is difficult to find granulomas in the biopsy.33

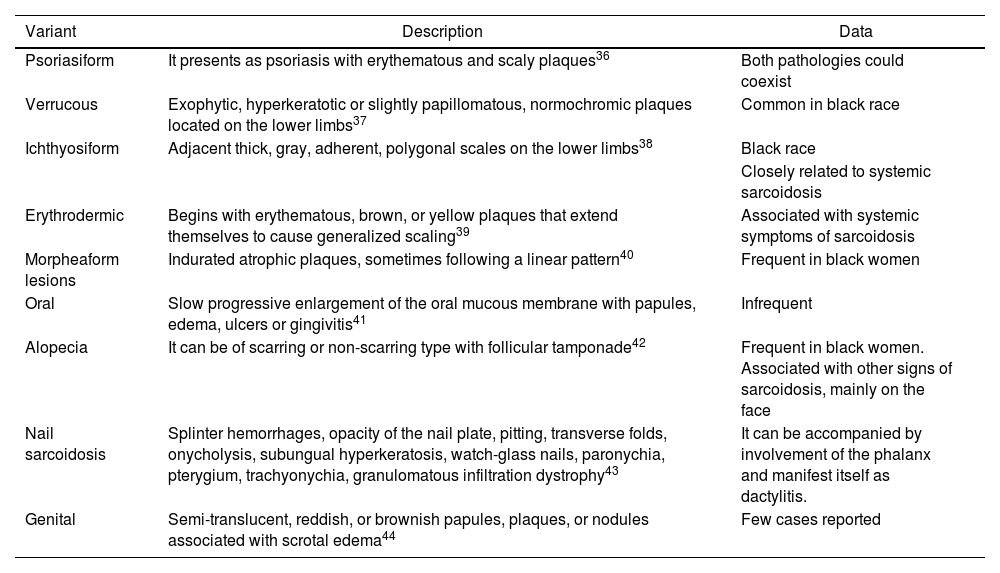

Lichenoid sarcoidosisIt is more common in children and appears as flat or dome-shaped normochromic macules and papules of 1–3 mm. They are located on the trunk, the limbs, or the face.34 The differential diagnosis is made with other lichenoid dermatoses such as lichen planus, lichen nitidus, lichenoid eruptions, and lupus erythematosus.35 Other rarer variants are described, which are presented in Table 1.

Other less common variants of cutaneous sarcoidosis.

| Variant | Description | Data |

|---|---|---|

| Psoriasiform | It presents as psoriasis with erythematous and scaly plaques36 | Both pathologies could coexist |

| Verrucous | Exophytic, hyperkeratotic or slightly papillomatous, normochromic plaques located on the lower limbs37 | Common in black race |

| Ichthyosiform | Adjacent thick, gray, adherent, polygonal scales on the lower limbs38 | Black race |

| Closely related to systemic sarcoidosis | ||

| Erythrodermic | Begins with erythematous, brown, or yellow plaques that extend themselves to cause generalized scaling39 | Associated with systemic symptoms of sarcoidosis |

| Morpheaform lesions | Indurated atrophic plaques, sometimes following a linear pattern40 | Frequent in black women |

| Oral | Slow progressive enlargement of the oral mucous membrane with papules, edema, ulcers or gingivitis41 | Infrequent |

| Alopecia | It can be of scarring or non-scarring type with follicular tamponade42 | Frequent in black women. Associated with other signs of sarcoidosis, mainly on the face |

| Nail sarcoidosis | Splinter hemorrhages, opacity of the nail plate, pitting, transverse folds, onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, watch-glass nails, paronychia, pterygium, trachyonychia, granulomatous infiltration dystrophy43 | It can be accompanied by involvement of the phalanx and manifest itself as dactylitis. |

| Genital | Semi-translucent, reddish, or brownish papules, plaques, or nodules associated with scrotal edema44 | Few cases reported |

The prognosis depends on the extent, severity, and systemic involvement. Maculopapular lesions, subcutaneous nodules, and scar sarcoidosis are usually transient, resolve spontaneously, or follow the course of the systemic disease.21 Plaques and lupus pernio have a more chronic course and are associated with severe lung disease and extrathoracic involvement.14,29

TreatmentSome of the skin lesions are transient and do not require treatment, unless they are clinically disfiguring, symptomatic, or ulcerative. Topical or intralesional steroids can be used in cases of localized disease.45,46 In case of affecting sites that have a higher risk of cutaneous atrophy, such as the face and intertriginous areas, low-potency steroids can be used combined with topical calcineurin inhibitors.47

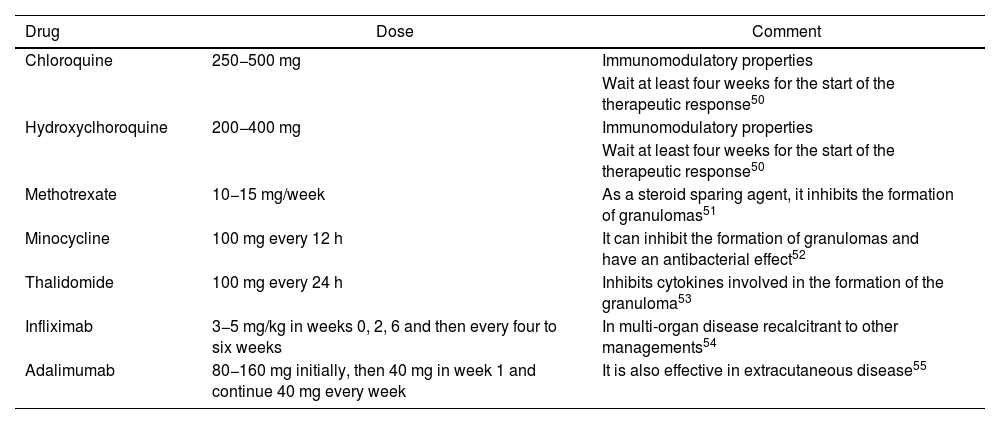

In the event that the lesions progress rapidly or are disfiguring, management with oral steroids should be started at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day of prednisone and gradually adjust the dose according to the response.48 In some occasions, lupus pernio may require oral steroids.49 For extensive involvement, where the use of topical agents would be impractical, or in cases of refractory lesions, there are multiple systemic treatment options that are summarized in Table 2.

Systemic treatment options for cutaneous sarcoidosis.

| Drug | Dose | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroquine | 250−500 mg | Immunomodulatory properties |

| Wait at least four weeks for the start of the therapeutic response50 | ||

| Hydroxyclhoroquine | 200−400 mg | Immunomodulatory properties |

| Wait at least four weeks for the start of the therapeutic response50 | ||

| Methotrexate | 10−15 mg/week | As a steroid sparing agent, it inhibits the formation of granulomas51 |

| Minocycline | 100 mg every 12 h | It can inhibit the formation of granulomas and have an antibacterial effect52 |

| Thalidomide | 100 mg every 24 h | Inhibits cytokines involved in the formation of the granuloma53 |

| Infliximab | 3−5 mg/kg in weeks 0, 2, 6 and then every four to six weeks | In multi-organ disease recalcitrant to other managements54 |

| Adalimumab | 80−160 mg initially, then 40 mg in week 1 and continue 40 mg every week | It is also effective in extracutaneous disease55 |

The non-specific manifestations of sarcoidosis are those that do not present with granulomas in the biopsy, but that doesn’t mean that they are less common.3

Erythema nodosumIt is the most common form of non-specific manifestations. It corresponds to a septal panniculitis without vasculitis, which manifests with painful and erythematous subcutaneous nodules of 1–6 cm. It presents a bilateral symmetrical distribution in the lower extremities, in the pretibial region, the ankles, the thighs, or even in the forearms. It resolves in one to six weeks and evolves as an ecchymosis.25 When it is accompanied by bilateral hilar lymphadenopathies and arthralgia, it is called Löfgren's syndrome. It occurs more frequently in Caucasian women, in winter and spring seasons.2 The polyarthralgias are located in the knees and ankles, the latter with very prominent periarticular inflammation. When it presents without erythema nodosum, it can be considered a variant of Löfgren’s syndrome and is found more commonly in men.56 Constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, malaise, fever, anterior uveitis, and peripheral facial paralysis may be found accompanying the classic triad.2

Treatment and prognosisFor erythema nodosum, rest, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), potassium iodide, or a short course of steroids must be guaranteed.57 For Löfgren’s syndrome, NSAIDs and colchicine may be sufficient, but in more severe cases the use of oral steroids may be required. This syndrome has generally a good prognosis and can have a spontaneous remission in one or two years.2

Other non-specific manifestationsOther cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis that do not present themselves with granulomas on biopsy include Hippocratic fingers, Sweet’s syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema multiforme, and prurigo.

ConclusionsSarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease that has a highly variable presentation when it affects the skin. The fact of finding non-caseating granulomas supports the diagnosis of sarcoidosis in the appropriate clinical context, however, it should be remembered that there are nonspecific lesions that will present a different histology. The case of a patient with subcutaneous sarcoidosis in which skin biopsy was of great help to establish the diagnosis was presented. There are several effective treatments for cutaneous sarcoidosis and these patients should be evaluated to rule out systemic disease, since the skin is often the first reflection of a multi-organ process.

FundingThis work has not received any type of funding.

Ethical considerationsThe author informs that she has obtained all the consents required by the current legislation for the publication of any personal data or images of patients, research subjects or other persons that appear in the materials sent. She has retained a written copy of all consents and, upon request, she agrees to provide copies or evidence that such consents have been obtained. In addition, she certifies that the work complies with current regulations on bioethical research.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.